Home > Articles > The Archives > The Old Mill Stream of Consciousness: John Hartford in the ‘90s

The Old Mill Stream of Consciousness: John Hartford in the ‘90s

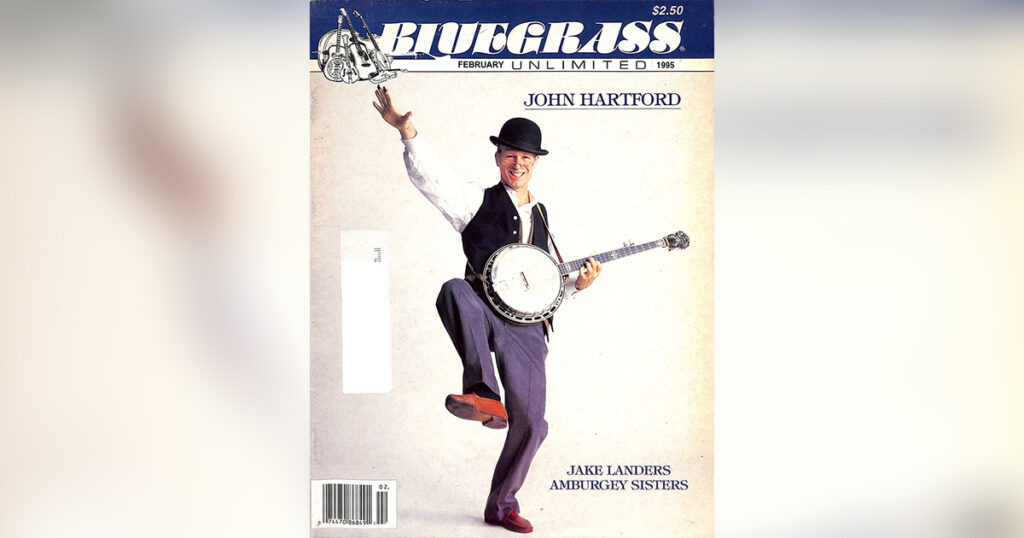

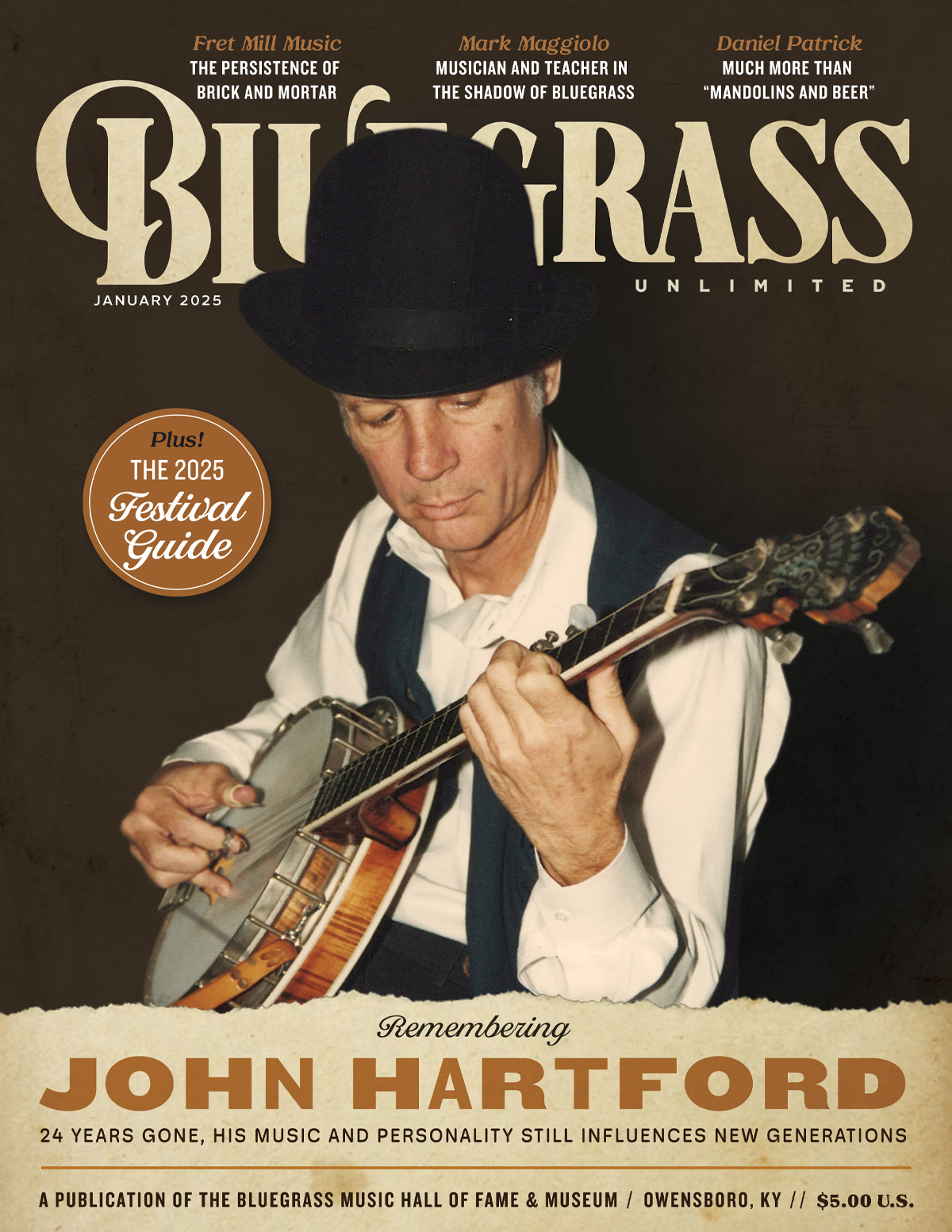

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1995, Volume 29, Number 2

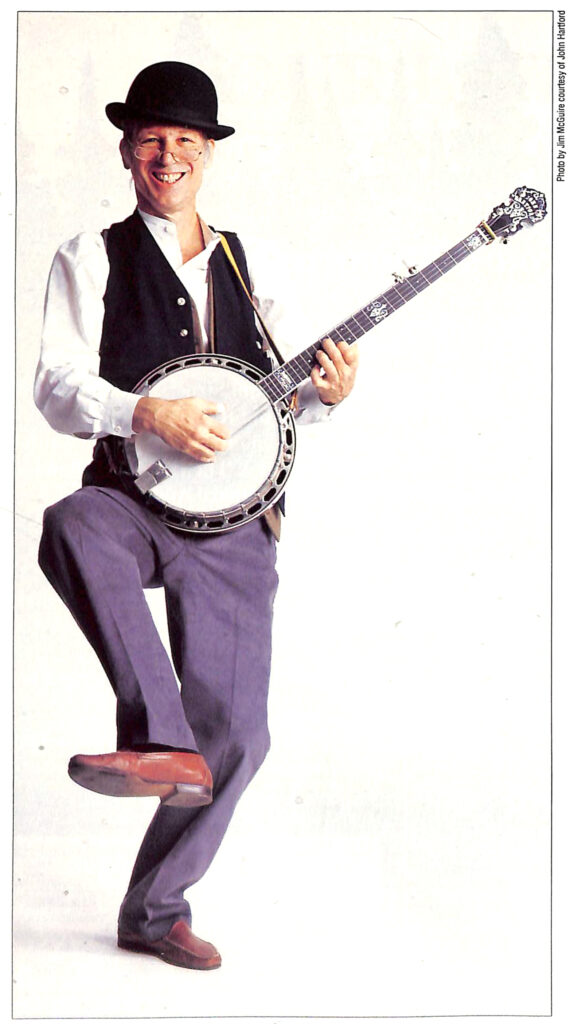

John Hartford keeps heading into the future by delving way back into the past. It’s not that Hartford stays lost in thoughts of by gone days; his busy career includes the recent release “The Walls We Bounce Off Of” on his Small Dog label, a research project that could be anything from a book to a TV documentary, an ongoing sideline as a steamboat pilot and a touring career that only recently slimmed from 200 to 150 dates a year.

But the singer, songwriter, banjoist, fiddler, steamboat pilot, author and record company exec definitely finds a lot of inspiration in older days, different ways and almost forgotten tunes.

“It’s just a labor of love,” Hartford, 56, said the other day at his home overlooking the Cumberland River, just north of Nashville. “I don’t know why, other than that to understand the future, you have to understand the past. I get fascinated with stuff of which there’s nothing written, so I have to go and find it myself.”

In the midst of his various other endeavors, Hartford’s engrossed in finding out everything he can about Ed Haley, an influential blind fiddle player who died 40 years ago. Haley had his greatest era of prominence from 1910-15 up to the ’30s and ’40s.

“He made home discs for people,” Hartford said. “He never played on the radio, but he played on the streets a lot in West Virginia and Kentucky. He had the same impact on old-time fiddle playing that Earl Scruggs had on the banjo.”

Some of Haley’s playing can be heard on a Rounder Records release called “Parkersburg Landing,” but Hartford is out to collect much more. In fact, if any Bluegrass Unlimited reader has information about Haley, Hartford asks to be dropped a line at Box 443, Madison, TN 37116. There’s deliberately no decision yet on the form in which his Haley research will emerge.

“I can maintain the quality of a project if I keep away horn the mechanics of, ‘Is this going to be a book? Is this going to be a record ? Is this going to be a TV special?’ I don’t want that to interfere with the quality of the project.”

Hartford’s deep interest in old-time fiddling should come as a surprise only to fans who remember him best from his years as a five-string wielding television star on the old Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour and Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour shows.

“For years I wanted to be a banjo player. My role model was Earl Scruggs; that’s who I wanted to be. But a lot of times people would say, ‘We’ve got (banjoist) Doug Dillard over here; we want you to play the fiddle.’

“I’ve always known a lot of the old tunes and I always kept the fiddling up, but it was always like a second instrument. When I went to California, it came in handy in my act.”

When Hartford formed a groundbreaking group—one that helped fuel the fires of newgrass—to record his “Aero Plain” album in the early 1970s, its members included the mighty Vassar Clements on fiddle. Clements kept the pressure up on Hartford to keep his bow rosined so that the two could play twin fiddles.

“Vassar got on me and insisted that I should play the fiddle. Then one day I realized that I really did love the fiddle. I realized that what I could play was adequate. I’ve been spending a lot of time in the last 10-15 years getting my own fiddle chops up to where I could play the music that I hear in my head closer to the way I heard it.”

Hartford’s son Jamie, himself now a budding recording artist on Arista Records, taught John to read music a few years ago, opening up new ways of thinking about fiddle and another window on the past. “Jamie said, ‘It’s not that hard.’”

Hartford said. “He figured out a way of explaining it to me that got through my thick head. I started studying fiddle tunes and where they came from and what made them tick. There’s a whole set of music that I grew up with that I wanted to know more about.

“I started buying every old fiddle tune book that I could find. Back in the 19th century it was more common for fiddle players to be able to read music than after the advent of the phonograph. In fact, tune collecting is old. There are bagpipe collections from the 17th and 18th centuries. The patricians would decide that these sorts of tunes were dying out and should be collected and they’d have one of their musicians sit down and write these things out and put them in their collection in their library.” It’s clear that Hartford’s long and deep acquaintance with old-time country is a continuing thread in his music and life. His two favorite fiddlers are the elusive old-time master Ed Haley and bluegrass veteran Benny Martin. Even Hartford’s mega-hit song, “Gentle On My Mind,” with its long strings of what sound like rolling Dylanesque lyrics, has some roots in the old-time fiddle style the writer learned as a youngster in St. Louis County.

“‘Gentle On My Mind’—one reason it sounds Dylanesque is that it’s what I’d call fiddle tune wording. When I was growing up, the music was always the first thing with me; when I would hear older people’s lyrics and even my own, I would just hear them as abstract sounds. The lyrics seemed so simple. There’s a list of about 25 words that these songs were made up of. I wanted them to be fascinating and interesting, so I kind of went to the wordy fiddle tune style so I could pack up more footage into it.

“‘Gentle On My Mind’ was written at a time when I was writing five, six, seven songs a day. I’d write when I got up in the morning. I would write lyrics just as fast as I could write ’em and then I would make up the melodies as I was recording the demos.”

Hartford’s most recent album, “The Walls We Bounce Off Of,” provides a plentiful measure of what might be called his old-mill-stream-of-consciousness style. The fiddle and banjo playing have Hartford’s distinctive touch and the lyrics are a good-natured waltz through some of the oddities, pleasures and displeasures of modern life. There’s lots of that “fiddle tune wording” in tunes such as the album-concluding “Hooter Thunkit,” where he sings about the “music seducing my mind.”

“You sure got that right/my wife says to me/ as I read her this scratchy old bad rhymery/You’re the last one to stop and the first one to stay/Til everyone’s cased up and gone.” Hartford’s themes are as old as dinner bells and pickers who don’t want to go home—or as topical as “Sexual Harassment.”

“If I whisper your name in some fake foreign accent/Would that be the same as sexual harassment?” he sings to his beloved in the song of that title.

The bluegrass side of Hartford’s music is heard in the lonesome flavor of certain songs, in the rolls of his low-tuned five-string and in the swoops and bluesy calls of his fiddle. “I have never made any bones about being bluegrass or being bluegrass-influenced,” he said. “I’ve always associated myself with bluegrass people and bluegrass players. And yet I’m not considered bluegrass. But, there are a lot of other people who are far less bluegrass than I that are considered bluegrass.”

The ways Hartford gets his music and other projects out the public these days are steeped in the philosophy that less is more. He started Small Dog Records after absorbing a truth taught him by wife Marie, a veteran of music publishing: When stars make records for a big company, the stars pay for the recording sessions themselves out of royalties, but the record company ends up owning the master tape.

“Now that I’m my own label is the first time I’ve made any money in the record business,” he said. Small Dog has released three discs as of this writing— “Cadillac Rag,” featuring Hartford and Mark Howard; “Going Back To Dixie,” a Hartford band album; and “The Walls We Bounce Off Of.” Two more are on the way, “Old Sport,” featuring Hartford and his old fiddle playing pal Texas Shorty and a live Hartford album recorded at State College, Pa.

His touring, in most cases as a solo act, is similarly self-contained. “We’ve got a camper with all our stuff in it,” he said. “Marie goes with me and sometimes Dustin my grandson goes with me. What makes the road the road is that you’re away from your family and your things.”

For the actual recording, Hartford also hoes his own row. “When I get my album together, I cut it here at home on a little cassette machine and take it out on a little old cassette and listen to it. If it works, OK; if not, I go back and work on it more before I go in with the musicians. I do a lot of sketching before I stretch canvas.”

So how does he get it all done? “I don’t watch much television,” Hartford said. “Songwriting, the lyric-writing end of that, that’s an ongoing thing. I carry 3×5 cards and write down ideas and put them in a file. And when I get time, I open up the file.”

There’s one part of the country music business, a highly traditional part, that Hartford has long wanted to join. “I would love to be on the Opry, but I’ve got a lot of other stuff to do and I don’t want to pester them down there,” he said. “I love the Grand Ole Opry; I’d go right over there and do it in a minute. But I’ve got other things that I have to do on Saturday nights. I’ve had my heartbroken enough in that area; it’s a whole lot easier to stay away from it.”

It’s certainly not as though Hartford needs the Opry to keep him booked. He’s out as often as he wants, playing festivals, clubs, theaters and other live music places. Not only that, he still takes his turn at piloting the steamboat Julia Belle Swain on the Mississippi every year. He’s written a children’s book Steamboat In A Cornfield, and was even heard as one of the voices in the high-profile PBS series The Civil War.

But in the final analysis, for all Hartford’s absorption in past ways and days, he’s as modern as they come. Why? Because he’s got his own style, his own thing, fashioned from building blocks gleaned all over die place and all through the years. And truly distinctive artists never go out of style.

“I have my ways of writing—I think they’re mine primarily,” Hartford said. “One of my biggest influences was Roger Miller. I certainly was influenced by Bob Dylan. And you may not readily, apparently hear this in my lyrics, but I was also influenced by bluegrass writers—Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt, Benny Martin. Benny Martin was a tremendous songwriting influence on me.

“My artistic thing is a little on the selfish side, but it seems to work for me—I do what’s in my heart. If it works that’s great, if not, then I haven’t wasted my time. The other side of dial is, if I do what’s in my heart, I’m not following the demographic trends and I’m not going to be a big monster act. But there will be somebody out there who will like what I do.”

Thomas Goldsmith is a frequent writer for the Nashville-based TENNESSEAN. He also is a freelance writer for several other music publications.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Love his music.