Home > Articles > The Archives > The New Grass Revival, Vol. 13 No. 5

The New Grass Revival, Vol. 13 No. 5

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1978

It was the summer of 1972 when I first heard the New Grass Revival. I was in the process of rediscovering bluegrass, a music remembered vaguely from childhood television shows at my aunt’s in Corbin, Kentucky, and vividly from my favorite first record, a worn out “78” of “Bile ’Em Cabbage Down.” My friends and I spent most of that summer travelling to festivals in Bean Blossom and Berryville and catching J.D. Crowe in little bars around Lexington and Louisville. The music we heard was largely traditional: Monroe, Ralph Stanley, Crowe was only mildly experimental then. It was the most exciting, the most personal music I’d ever heard.

Its setting was the land I came from and loved. Its fast pace and complex rhythms; the high nasal singing: the peculiar words and phrasings of the lyrics echoed the cadencies of voices from my youth.

At the same time, the music was painfully alienating. It all seemed to happen in the past, in a time that belonged to my parents or, more often, my grandparents. It seemed as if all the good times it spoke of were indeed past and gone, and there was no way to integrate the music into the life of a young city woman maturing in the turbulent sixties, except as a memory, a family heirloom.

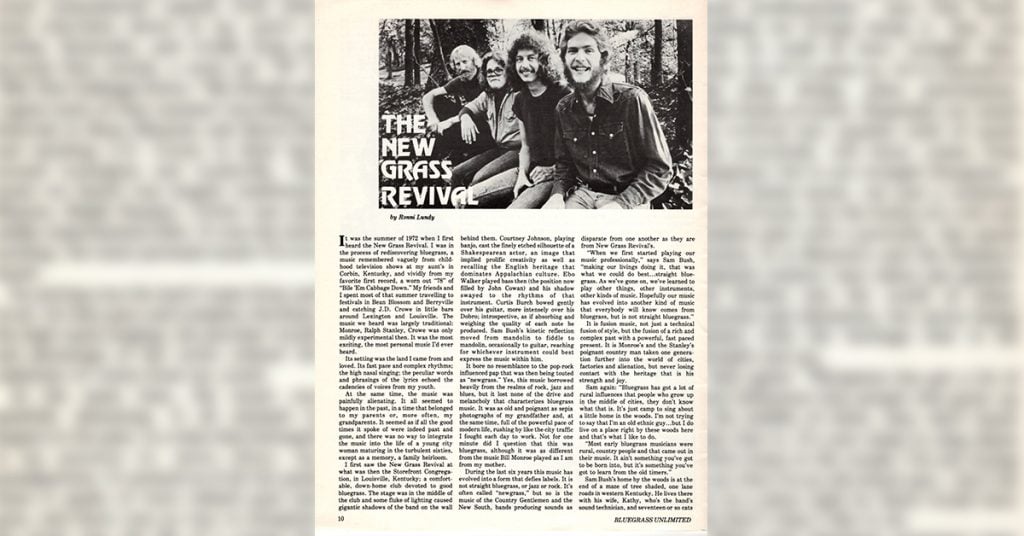

I first saw the New Grass Revival at what was then the Storefront Congregation, in Louisville, Kentucky; a comfortable, down-home club devoted to good bluegrass. The stage was in the middle of the club and some fluke of lighting caused gigantic shadows of the band on the wall behind them. Courtney Johnson, playing banjo, cast the finely etched silhouette of a Shakespearean actor, an image that implied prolific creativity as well as recalling the English heritage that dominates Appalachian culture. Ebo Walker played bass then (the position now filled by John Cowan) and his shadow swayed to the rhythms of that instrument. Curtis Burch bowed gently over his guitar, more intensely over his Dobro; introspective, as if absorbing and weighing the quality of each note he produced. Sam Bush’s kinetic reflection moved from mandolin to fiddle to mandolin, occasionally to guitar, reaching for whichever instrument could best express the music within him.

It bore no resemblance to the pop-rock influenced pap that was then being touted as “newgrass.” Yes, this music borrowed heavily from the realms of rock, jazz and blues, but it lost none of the drive and melancholy that characterizes bluegrass music. It was as old and poignant as sepia photographs of my grandfather and, at the same time, full of the powerful pace of modern life, rushing by like the city traffic I fought each day to work. Not for one minute did I question that this was bluegrass, although it was as different from the music Bill Monroe played as I am from my mother.

During the last six years this music has evolved into a form that defies labels. It is not straight bluegrass, or jazz or rock. It’s often called “newgrass,” but so is the music of the Country Gentlemen and the New South, bands producing sounds as disparate from one another as they are from New Grass Revival’s.

“When we first started playing our music professionally,” says Sam Bush, “making our livings doing it, that was what we could do best…straight bluegrass. As we’ve gone on, we’ve learned to play other things, other instruments, other kinds of music. Hopefully our music has evolved into another kind of music that everybody will know comes from bluegrass, but is not straight bluegrass.”

It is fusion music, not just a technical fusion of style, but the fusion of a rich and complex past with a powerful, fast paced present. It is Monroe’s and the Stanley’s poignant country man taken one generation further into the world of cities, factories and alienation, but never losing contact with the heritage that is his strength and joy.

Sam again: “Bluegrass has got a lot of rural influences that people who grow up in the middle of cities, they don’t know what that is. It’s just camp to sing about a little home in the woods. I’m not trying to say that I’m an old ethnic guy…but I do live on a place right by these woods here and that’s what I like to do.

“Most early bluegrass musicians were rural, country people and that came out in their music. It ain’t something you’ve got to be born into, but it’s something you’ve got to learn from the old timers.”

Sam Bush’s home by the woods is at the end of a maze of tree shaded, one lane roads in western Kentucky. He lives there with his wife, Kathy, who’s the band’s sound technician, and seventeen or so cats named after musical luminaries, including his hero, Jethro Burns. The kitchen comfortably blends eras with an antique pie safe in one corner, a Melita instant coffee machine in another. In the living room you can catch glimpses of the hundred-fifty year old log walls underneath the 1940’s wall paper. Sam and Kathy talk about restoring the house, but it’s a hard thing to imagine when you spend forty-two weeks a year on the road.

When I first met Sam Bush he was too young to drink in the bar he was playing in. He brought to his music the passionate defiance inevitable with youth and brilliance. He was hell-bent on playing everything as hard and perfectly as he could.

Time and mellowing are words that tend to travel in tandem and with the passage of seven years, both Sam and his approach to music have mellowed. Age has given him more than a few invisible grey hairs in a slightly more conservative haircut. His music is still intense, extraordinary, and complex, but backed now by a confidence, a subtle self- assurance that says you don’t have to play every hot lick you know every time you play.

As do all the members of the band, Sam has a finely articulated concept of music. He has a strong sense of where his music’s going and a vivid recollection of where it came from.

“I was interested in music before I ever thought about learning to play. I know now that I was thinking about it. My dad used to play records and I would try to hum. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I now know that I was trying to hum a bass part. I listened to these fiddle records my dad had (mostly Tommy Jackson) and he always had a mandolin and a fiddle laying around the house. He played fiddle more than anything and I just got interested because my dad just loves music.

“The one thing that made me want to play was watching the Flatt and Scruggs show one time. I used to watch Flatt and Scruggs every Saturday afternoon. Lester was up there MCing and all of a sudden this little boy comes up to him and tugs him on the sleeve and Lester says: ‘What do you want?’

(Little boy answers): ‘I wanna pick.’ And so Lester pulls a pick out of his pocket and says: ‘Well, here.’

And this little boy went over and they had about two or three coke boxes so he could reach the mike and he just picked the dickens out of it. It was Ricky Skaggs, and I said: ‘I wonder if I could…I bet I could do that!’

“So I started wanting a mandolin. My dad would take me to the doctor in Louisville. I had bad lungs, asthmatic… and stuff. And then he’d take me to Durlaufs and show me all these Gibson mandolins and I’d want one. So when I was 11, in December, with some money I’d saved up I bought my first mandolin. I started playing mandolin when I was 11.

“I wasn’t really aware of bluegrass at that time. I was listening to the mandolin player on the Tommy Jackson records. Red Rector.

“After a while I started getting interested in bluegrass. Wayne Stewart and I went to the Roanoke (Fincastle) Bluegrass Festival in ’65. That was the first time I heard just real bluegrass and I didn’t know that mandolins were used like that. All the hot mandolin players were there and that’s how I got turned on to bluegrass.”

Sam took up fiddling, as well, and his first year of playing he placed fifth in the National contest in Weiser, Idaho. The three following years he finished first.

His first appearance on record was “Poor Richard’s Almanac” with Wayne and Alan Munde. Courtney Johnson later took Alan’s place on banjo and in 1970, Courtney and Sam joined the Bluegrass Alliance.

When Courtney Johnson opens his mouth, pure western Kentucky falls out. Firmly entrenched in the land he came from, his present house is only a few miles from the place where he was born and raised. There’s a creek behind it, a CB radio in it and a truck with the hood up next to it. Courtney Johnson’s an occasional mechanic, a man who likes to tinker with the possibilities, to explore.

A silent, taciturn personality on stage, often playing banjo with his eyes closed, Courtney comes alive when he talks about the things he enjoys. Eyes twinkling, laughing often, I get the feeling from our conversation that there’s nothing he loves quite so much as pickin’ banjo, especially with the Revival.

“I first started playing guitar when I was about seven years old and I was influenced by country then a lot, because my dad was into it and sang and played that. I heard a lot of frailing type banjo, too, when I was growing up because we always went to dances.

“But I never really got into banjo until I was 25 years old. My brother traded for one and I just started fooling with it— learned how to play it. I just quit playing guitar then.

“My first influence, what I first learned to play was Ralph Stanley type. I listened to The Stanley Brothers then a lot, really more than Scruggs. But Alan Munde had more influence on me than anyone else. I first heard him in, say, ’66 or ’67, and he was playing fiddle tunes then and it just blew me away. I’d never heard anybody do that. Texas type fiddle tunes, you know, a lot of notes. That’s what turned me around on banjo.

“I met Sam from playing on Channel 13, a local television station. They had a Saturday night thing. Sam and his sisters were playing and singing then.”

It was Courtney who encouraged Sam and Alan Munde to get together the first time

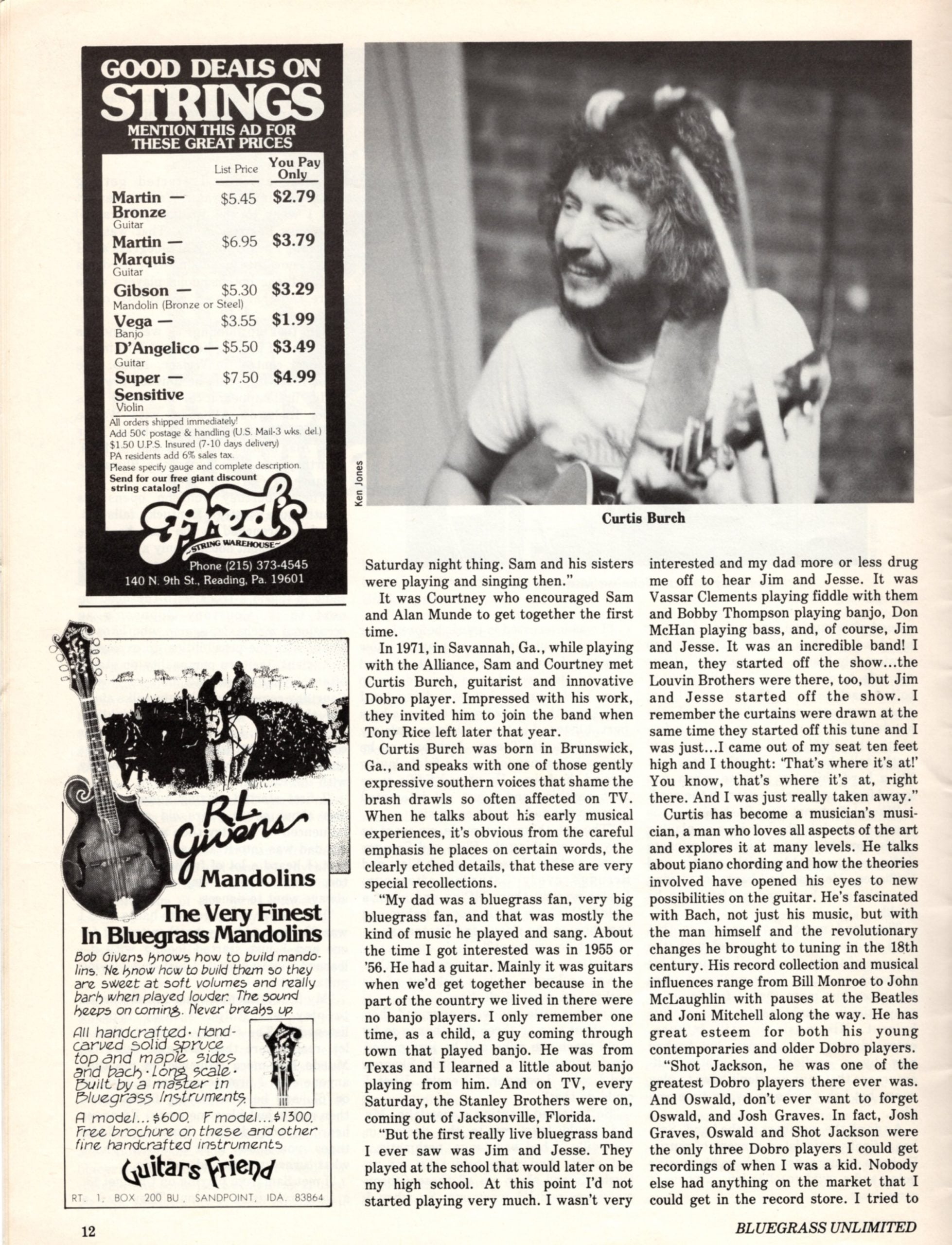

In 1971, in Savannah, Ga., while playing with the Alliance, Sam and Courtney met Curtis Burch, guitarist and innovative Dobro player. Impressed with his work, they invited him to join the band when Tony Rice left later that year.

Curtis Burch was born in Brunswick, Ga., and speaks with one of those gently expressive southern voices that shame the brash drawls so often affected on TV. When he talks about his early musical experiences, it’s obvious from the careful emphasis he places on certain words, the clearly etched details, that these are very special recollections.

“My dad was a bluegrass fan, very big bluegrass fan, and that was mostly the kind of music he played and sang. About the time I got interested was in 1955 or ’56. He had a guitar. Mainly it was guitars when we’d get together because in the part of the country we lived in there were no banjo players. I only remember one time, as a child, a guy coming through town that played banjo. He was from Texas and I learned a little about banjo playing from him. And on TV, every Saturday, the Stanley Brothers were on, coming out of Jacksonville, Florida.

“But the first really live bluegrass band I ever saw was Jim and Jesse. They played at the school that would later on be my high school. At this point I’d not started playing very much. I wasn’t very interested and my dad more or less drug me off to hear Jim and Jesse. It was Vassar Clements playing fiddle with them and Bobby Thompson playing banjo, Don McHan playing bass, and, of course, Jim and Jesse. It was an incredible band! I mean, they started off the show…the Louvin Brothers were there, too, but Jim and Jesse started off the show. I remember the curtains were drawn at the same time they started off this tune and I was just…I came out of my seat ten feet high and I thought: ‘That’s where it’s at!’ You know, that’s where it’s at, right there. And I was just really taken away.”

Curtis has become a musician’s musician, a man who loves all aspects of the art and explores it at many levels. He talks about piano chording and how the theories involved have opened his eyes to new possibilities on the guitar. He’s fascinated with Bach, not just his music, but with the man himself and the revolutionary changes he brought to tuning in the 18th century. His record collection and musical influences range from Bill Monroe to John McLaughlin with pauses at the Beatles and Joni Mitchell along the way. He has great esteem for both his young contemporaries and older Dobro players.

“Shot Jackson, he was one of the greatest Dobro players there ever was. And Oswald, don’t ever want to forget Oswald, and Josh Graves. In fact, Josh Graves, Oswald and Shot Jackson were the only three Dobro players I could get recordings of when I was a kid. Nobody else had anything on the market that I could get in the record store. I tried to take those three guys’styles and combine them into my own ideas and that’s who I learned to play Dobro from. I think Jerry Douglas, Tut Taylor, Mike Auldridge, Buddy Emmons, I think these guys have done more with the Dobro than anybody. All these guys are really tremendous Dobro players. I think they use the instrument for what it fits best, too.”

But if Curtis’ taste in music is somewhat eclectic, bluegrass was his first and is still his greatest love.

“Bluegrass is what I played more than any other kind of music and I love it; but I also wanted music as a profession and so I came to a point where I saw that I was not going to make it as a professional musician by playing for a straight bluegrass group that was established.”

Curtis’ professional career began with the Bluegrass Alliance in November of 1971. At that time the band included Lonnie Peerce, fiddle; Sam Bush, mandolin; Ebo Walker, bass and Courtney Johnson, banjo.

Bluegrass is a field of music where entire bands often change overnight leaving behind only a name and the musician most associated with that name. New Grass Revival was such a band, moving fully formed from Lonnie Peerce and the name, Bluegrass Alliance, in 1972. Peerce has formed several successful Alliances since that time, but New Grass’ only major change has involved bass players.

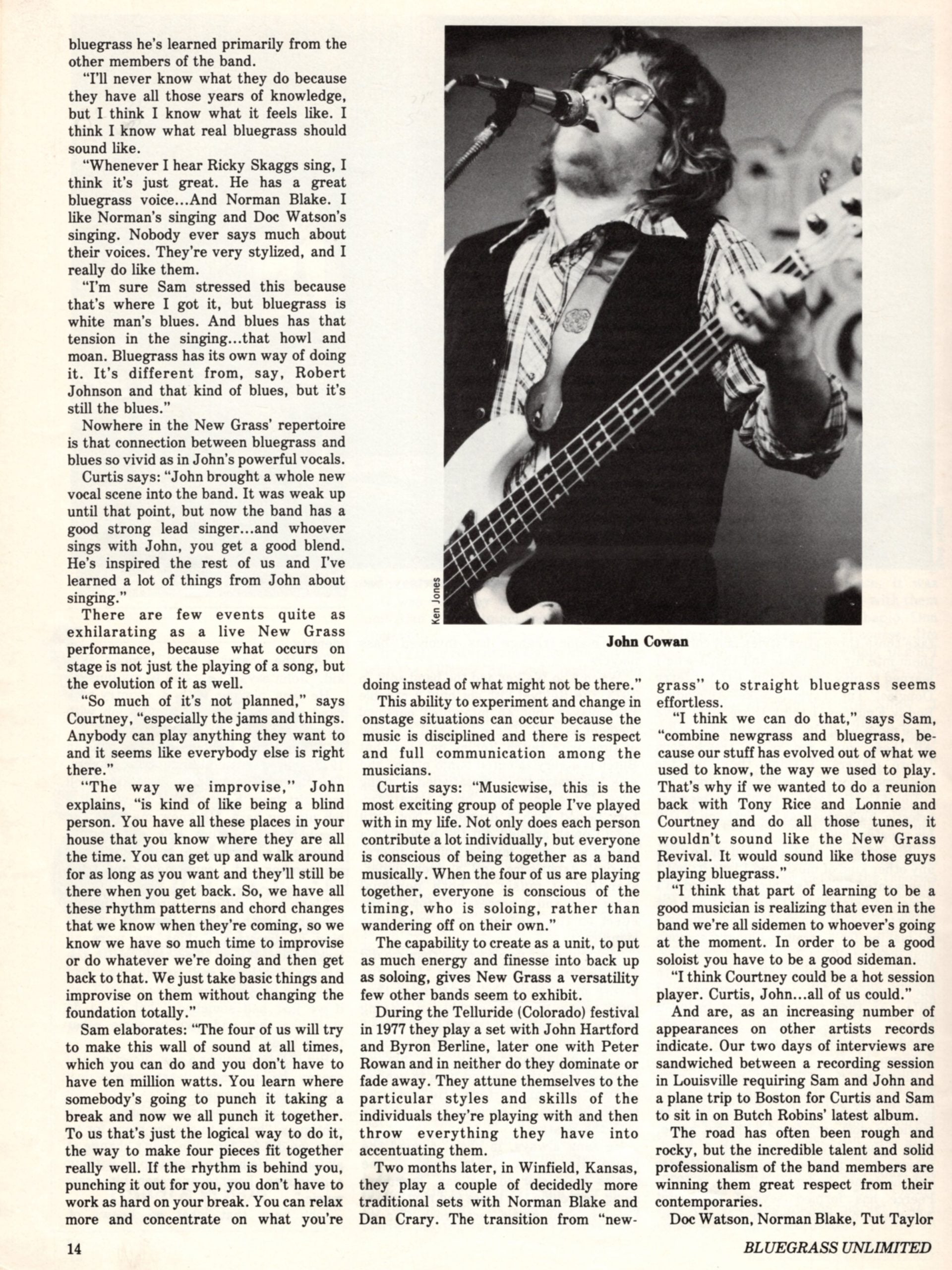

When Ebo Walker and the band split in 1973, the Revival lost not only a capable bass player, but an intangible personal element as well. There followed a period of time with Butch Robins on bass, but Butch is a very talented banjo player and was understandably dissatisfied playing bass. There was also a brief, unsatisfactory period with a drummer. Not until John Cowan arrived did the band find a bassist with great musical ability, diverse musical experience and a deep understanding of music as both personal expression and a process of growth. His effect on the band has been more than significant.

“John just lets us play more than we did ever before,” says Courtney. “John just knows more about his instrument than most people do. He’s capable of playing with us and that’s just turned us all loose.”

John’s musical background is not a typical bluegrass story. He played trumpet first, then bowed bass in school, electric bass at thirteen. He got into music, he says: “…because I was in love with the Beatles.”

He sang always, in choir, around the house. He was a typical child of the sixties-transistor to his ear, humming along, searching the lyrics and rhythms of Presley, soul music, acid rock, for an identity.

“All the phases I went through as a kid,” John says, “I applied to my music.”

He was playing with a country-rock band when he heard about the job with New Grass Revival.

“When Butch Robbins quit the band in 1973, they were auditioning bass players. They asked Kenny Smith (a rock and roll guitarist from Kentucky) if he wanted a job playing bass. He knew me from the Cumberlands because he’s a friend of theirs and so am I, so he gave New Grass my number and I came down and tried out.”

“John had a different direction that he brought in with us,” says Sam. “It was the kind of direction I think we were all looking for. We all liked to listen to the Allman Brothers and people who had really hot bass players, and we’d go: ‘God, if we just had somebody that could do stuff like that and give us some other things to do.’”

But if John brought a new direction and energy, he also had to learn a great deal about bluegrass music.

“When John came into the band,” Sam continues, “he had to change more for us than we did for him. We didn’t change at all for him. He had to learn to play without a drummer, how to approach bluegrass music.”

John says that what he knows of bluegrass he’s learned primarily from the other members of the band.

“I’ll never know what they do because they have all those years of knowledge, but I think I know what it feels like. I think I know what real bluegrass should sound like.

“Whenever I hear Ricky Skaggs sing, I think it’s just great. He has a great bluegrass voice…And Norman Blake. I like Norman’s singing and Doc Watson’s singing. Nobody ever says much about their voices. They’re very stylized, and I really do like them.

“I’m sure Sam stressed this because that’s where I got it, but bluegrass is white man’s blues. And blues has that tension in the singing…that howl and moan. Bluegrass has its own way of doing it. It’s different from, say, Robert Johnson and that kind of blues, but it’s still the blues.”

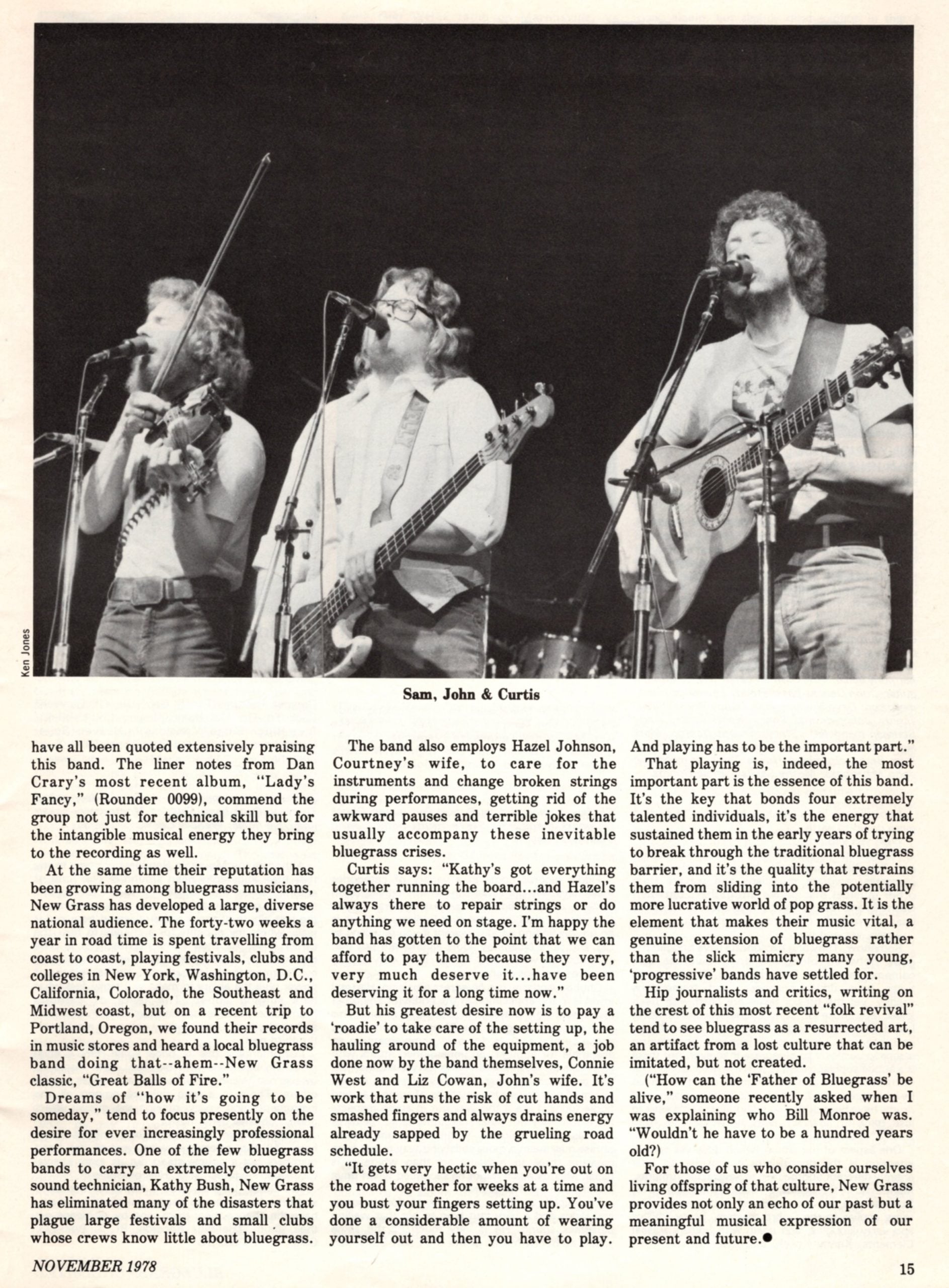

Nowhere in the New Grass’ repertoire is that connection between bluegrass and blues so vivid as in John’s powerful vocals.

Curtis says: “John brought a whole new vocal scene into the band. It was weak up until that point, but now the band has a good strong lead singer…and whoever sings with John, you get a good blend. He’s inspired the rest of us and I’ve learned a lot of things from John about singing.”

There are few events quite as exhilarating as a live New Grass performance, because what occurs on stage is not just the playing of a song, but the evolution of it as well.

“So much of it’s not planned,” says Courtney, “especially the jams and things. Anybody can play anything they want to and it seems like everybody else is right there.”

“The way we improvise,” John explains, “is kind of like being a blind person. You have all these places in your house that you know where they are all the time. You can get up and walk around for as long as you want and they’ll still be there when you get back. So, we have all these rhythm patterns and chord changes that we know when they’re coming, so we know we have so much time to improvise or do whatever we’re doing and then get back to that. We just take basic things and improvise on them without changing the foundation totally.”

Sam elaborates: “The four of us will try to make this wall of sound at all times, which you can do and you don’t have to have ten million watts. You learn where somebody’s going to punch it taking a break and now we all punch it together. To us that’s just the logical way to do it, the way to make four pieces fit together really well. If the rhythm is behind you, punching it out for you, you don’t have to work as hard on your break. You can relax more and concentrate on what you’re doing instead of what might not be there.” This ability to experiment and change in onstage situations can occur because the music is disciplined and there is respect and full communication among the musicians.

Curtis says: “Musicwise, this is the most exciting group of people I’ve played with in my life. Not only does each person contribute a lot individually, but everyone is conscious of being together as a band musically. When the four of us are playing together, everyone is conscious of the timing, who is soloing, rather than wandering off on their own.”

The capability to create as a unit, to put as much energy and finesse into back up as soloing, gives New Grass a versatility few other bands seem to exhibit.

During the Telluride (Colorado) festival in 1977 they play a set with John Hartford and Byron Berline, later one with Peter Rowan and in neither do they dominate or fade away. They attune themselves to the particular styles and skills of the individuals they’re playing with and then throw everything they have into accentuating them.

Two months later, in Winfield, Kansas, they play a couple of decidedly more traditional sets with Norman Blake and Dan Crary. The transition from “newgrass” to straight bluegrass seems effortless.

“I think we can do that,” says Sam, “combine newgrass and bluegrass, because our stuff has evolved out of what we used to know, the way we used to play. That’s why if we wanted to do a reunion back with Tony Rice and Lonnie and Courtney and do all those tunes, it wouldn’t sound like the New Grass Revival. It would sound like those guys playing bluegrass.”

“I think that part of learning to be a good musician is realizing that even in the band we’re all sidemen to whoever’s going at the moment. In order to be a good soloist you have to be a good sideman.

“I think Courtney could be a hot session player. Curtis, John…all of us could.” And are, as an increasing number of appearances on other artists records indicate. Our two days of interviews are sandwiched between a recording session in Louisville requiring Sam and John and a plane trip to Boston for Curtis and Sam to sit in on Butch Robins’ latest album.

The road has often been rough and rocky, but the incredible talent and solid professionalism of the band members are winning them great respect from their contemporaries.

Doc Watson, Norman Blake, Tut Taylor have all been quoted extensively praising this band. The liner notes from Dan Crary’s most recent album, “Lady’s Fancy,” (Rounder 0099), commend the group not just for technical skill but for the intangible musical energy they bring to the recording as well.

At the same time their reputation has been growing among bluegrass musicians. New Grass has developed a large, diverse national audience. The forty-two weeks a year in road time is spent travelling from coast to coast, playing festivals, clubs and colleges in New York, Washington, D.C., California, Colorado, the Southeast and Midwest coast, but on a recent trip to Portland, Oregon, we found their records in music stores and heard a local bluegrass band doing that–ahem–New Grass classic, “Great Balls of Fire.”

Dreams of “how it’s going to be someday,” tend to focus presently on the desire for ever increasingly professional performances. One of the few bluegrass bands to carry an extremely competent sound technician, Kathy Bush, New Grass has eliminated many of the disasters that plague large festivals and small clubs whose crews know little about bluegrass.

The band also employs Hazel Johnson, Courtney’s wife, to care for the instruments and change broken strings during performances, getting rid of the awkward pauses and terrible jokes that usually accompany these inevitable bluegrass crises.

Curtis says: “Kathy’s got everything together running the board…and Hazel’s always there to repair strings or do anything we need on stage. I’m happy the band has gotten to the point that we can afford to pay them because they very, very much deserve it…have been deserving it for a long time now.”

But his greatest desire now is to pay a ‘roadie’ to take care of the setting up, the hauling around of the equipment, a job done now by the band themselves, Connie West and Liz Cowan, John’s wife. It’s work that runs the risk of cut hands and smashed fingers and always drains energy already sapped by the grueling road schedule.

“It gets very hectic when you’re out on the road together for weeks at a time and you bust your fingers setting up. You’ve done a considerable amount of wearing yourself out and then you have to play. And playing has to be the important part.”

That playing is, indeed, the most important part is the essence of this band. It’s the key that bonds four extremely talented individuals, it’s the energy that sustained them in the early years of trying to break through the traditional bluegrass barrier, and it’s the quality that restrains them from sliding into the potentially more lucrative world of pop grass. It is the element that makes their music vital, a genuine extension of bluegrass rather than the slick mimicry many young, ‘progressive’ bands have settled for.

Hip journalists and critics, writing on the crest of this most recent “folk revival” tend to see bluegrass as a resurrected art, an artifact from a lost culture that can be imitated, but not created.

(“How can the ‘Father of Bluegrass’ be alive,” someone recently asked when I was explaining who Bill Monroe was. “Wouldn’t he have to be a hundred years old?)

For those of us who consider ourselves living offspring of that culture. New Grass provides not only an echo of our past but a meaningful musical expression of our present and future.*