Home > Articles > The Archives > The Nashville Bluegrass Scene and J.T. Gray’s Station Inn

The Nashville Bluegrass Scene and J.T. Gray’s Station Inn

Photos by Lance LeRoy

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1982, Volume 17, Number 4

The classic bluegrass music sound as most refer to it today was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on a Saturday night in the latter part of 1945, when Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, Howard (Cedric Rainwater) Watts and “Chubby” Wise got together for the first time and—less than an hour later—went on the Grand Ole Opry stage and WSM’s microphones to show the world how it should be done.

Today, roughly a dozen of the top names on the bluegrass festival circuit either live in the Nashville area or have their booking representation there. Bill Monroe is enshrined in the city’s Country Music Hall Of Fame and makes rather frequent appearances on prime-time network television productions. These extravaganzas almost invariably are either taped or presented live from Music City, U.S.A., as are many nationally broadcast awards shows involving a bluegrass category. When viewed from this perspective, Nashville then is one of the nation’s most important concentrations of bluegrass activity.

With these facts in mind, the logical conclusion would seem to be that bluegrass music fans represent a sizeable segment of the Nashville music community. This is far from the case, however. Unlike such a mecca for bluegrass as Washington, D.C., Nashville. has no hotbed of fan interest in its surrounding area to adequately support a major bluegrass concert. As in most cities, musical tastes of the vast majority of Nashvillians are trendy and fans flock to whatever happens to be riding Billboard’s charts of crossover music, posing under the guise of country music.

Indeed the fusion of country-rock (“crock” music to disgusted old line country fans) now permeates the Nashville music scene, eliminating any distinction between country, pop and soft rock and forcing both bluegrass and big band music into a minority status. Bluegrass occupied a prominent role in country music—as did the big bands in pop music—as recently as the early sixties.

In general, Nashville’s “country” record producers and music business executives have followed the line of smallest resistance, to say the least. The likes of Alabama, Olivia Newton-John, The Oak Ridge Boys, et al, feast at the gourmet table. One of the few crumbs offered bluegrass from that “table” on the nationally telecast awards show this past June as the kickoff to Fan Fair developed an especially bitter taste. Four of the five finalists for Bluegrass Act of The Year had little current connection with bluegrass music. The international publication who conducted the poll among their readers noted however that the awards were “fan-voted” but the segment came off as an affront to working professional bluegrass artists.

Although not the subject of this story, it should be noted that gospel music fared little better. Imagine the frustration of established, top name gospel groups that work 200 days a year on the road promoting their music, only to see the Hee Haw Quartet voted as Gospel Act Of The Year in this same “fan-voted” award for 1982.

The problem in both of the above instances is that those responding to the publication’s poll were neither bluegrass music fans nor gospel music fans and they had little knowledge of either. They are fans of modern country music. Yet it is their vote that determines who will step forward in front of TV cameras and a nationwide audience to bask in the spotlights and receive accolades as Bluegrass Act Of The Year.

Plainly, the people who orchestrate this scene from their Music Row offices have sought one thing: that is financial rather than aesthetic success. It’s hard to argue against financial success and the music industry in Nashville has grown to enormous proportions. More and more network radio and television and cable presentations are originating from Nashville studios and it is estimated that the inner city and its environs hold more than 300 recording and demo studios, countless hundreds of publishing operations and many booking agencies and other music-related activities. But among the metropolitan area’s 600,000-plus inhabitants is a very active and vital community made up of genuine, card-carrying bluegrass people. Their three primary gathering places are the Grand Ole Opry backstage, the Station Inn, and the Bluegrass Inn, the latter being Nashville’s oldest bluegrass club. Bluegrass is played in other places about town such as being a regular feature at Opryland but the environment isn’t the same.

At its annual Fan Fair charity fundraiser, Opry management devotes an entire afternoon to a bluegrass concert, plus an additional day with its Grand Masters Fiddlin’ Contest. Despite the as yet unreplaced loss in 1979 by the death of Lester Flatt, the Grand Ole Opry cast still includes five basically bluegrass acts.

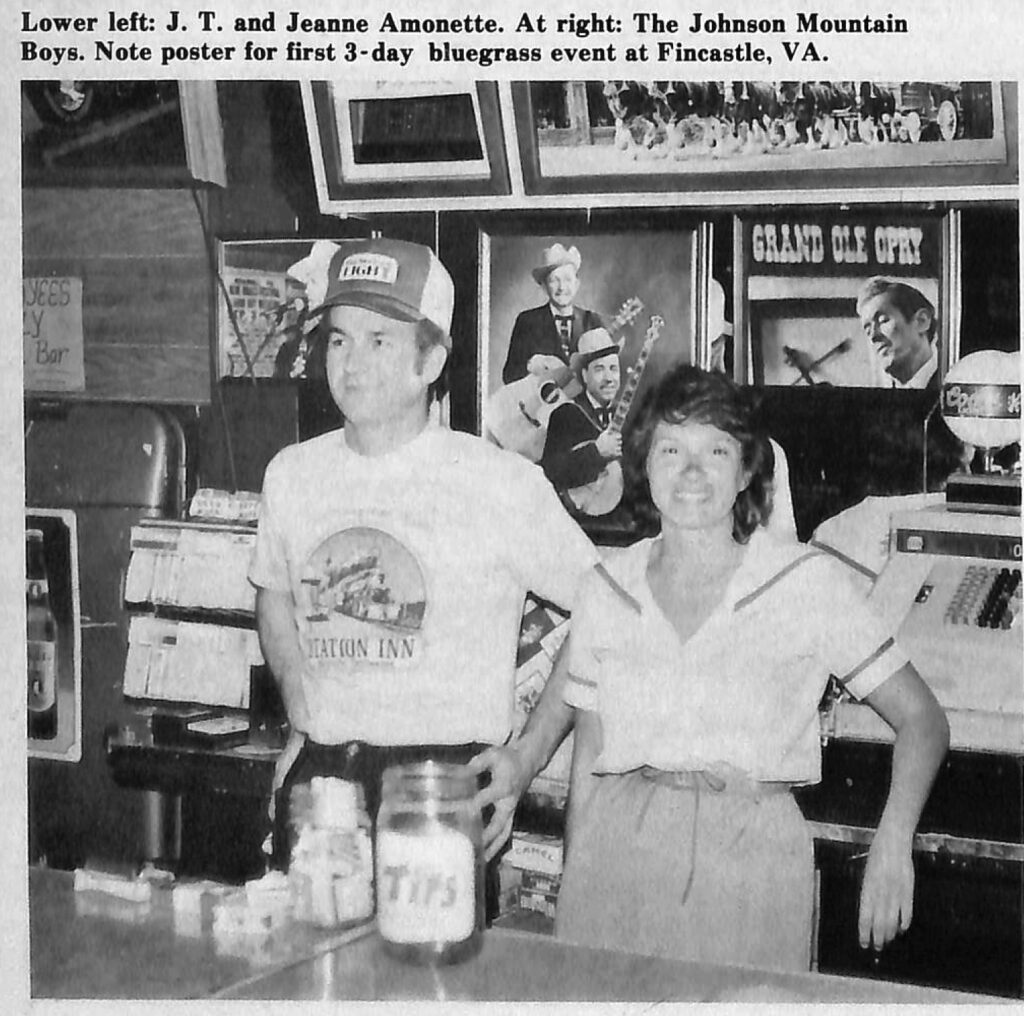

The “cast” of the Station Inn is not so clearly defined as that of the Opry but it is no less talented. Musicians performing there include its owner, J.T. Gray and the loosely knit group making up his Nashville Skyline. Open six nights a week, Tuesday through Sunday, it would be a rare evening that the audience didn’t include from one to a dozen or more nationally known bluegrass musicians who dropped in to listen and mingle with friends but frequently wind up in a serious jam session on stage.

While the Station Inn name in Nashville dates from 1974, the real story of what is now one of the city’s bluegrass hubs centers around J.T. Gray. A native of Corinth, Mississippi, J.T. is from a musical family that included his three brothers and three sisters. His first exposure to country music was at Corinth’s Coliseum Theatre—an institution in itself—where he saw the likes of Flatt & Scruggs and Jerry Lee Lewis perform. Moving to Nashville in 1971, he became interested in bluegrass in earnest and began playing bass in local clubs and also working road dates with different groups, the last being a stint with Jimmy Martin’s Sunny Mountain Boys from March through October, 1980.

“The original owners of the Station Inn in 1974 were Red and Birdie Smith; Bob Fowler, Jim Bornstein and Marty and Charmaine Lanham,” Gray recalls. “They needed a place to pick and just sort of got together. It was over on 28th Avenue then, just a few doors off West End Avenue, in the Centennial Park and Vanderbilt University area. It had a bar in the front and the music room was a few steps up and in the back. It only seated about 70 at best. That’s where the ‘world famous’ thing came about. One time a convention of ministers of all things came in and they were from countries all over Europe. Some of them remarked that they had already heard about the Station Inn back home and laughed about its being ‘world famous.’ They kind of carried it on and used it as a slogan but other places have picked up on it and now everything in town’s ‘world famous.’”

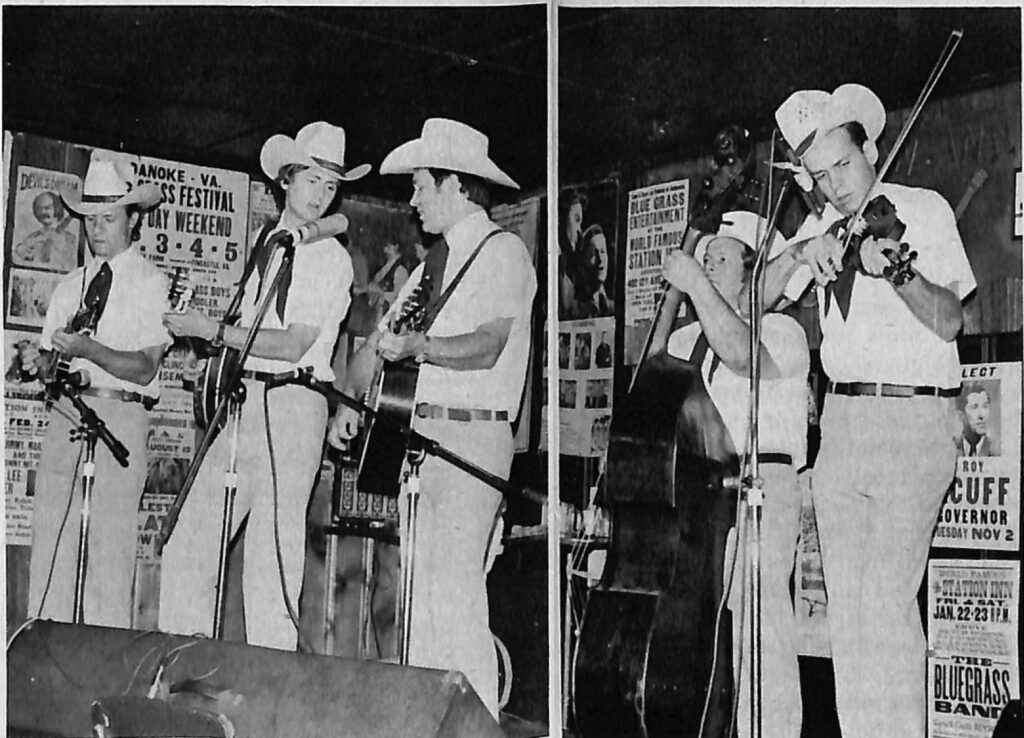

“I think it was sometime in 1978,” Gray continues, “when the building on 28th Avenue was torn down. Cliff Myers opened it here right after the old place closed and I bought it in March, 1981.” Located at 402 12th Avenue South in a rundown block of vacant houses and old industrial buildings just two blocks off bustling Broadway, the Station Inn has that special “atmosphere” that bluegrass fans hold near and dear. The interior walls are lined solidly from front to rear with more than 150 randomly-placed photos, show posters and other items of nostalgia, many of which are collector’s items. Included is a large poster [not a reproduction] announcing the lineup for what is generally conceded to be the first weekend gathering to be called a “bluegrass festival” in Fincastle, Virginia, on Labor Day weekend. Although not indicated on the poster of course, the year was 1965.

The skeptical out of town visitor is immediately disarmed upon entering by the warm and familiar surroundings and the array of friendly, outgoing people inside, not the least of whom are J.T. himself and his staff, consisting of Jeanne Amonette and Marguerite Donald. At various times either Diane Bouska, Arlene White or Noel (Punkin) Duncan will be found tending the door. The entry of a regular customer (J.T. likes to call them “friends”) brings on shouted greetings, a round of handshakes and a brown, longneck bottle of the customer’s favorite poison opened and waiting, thanks to an alert bartender in the rear.

Whether dictated by policy or simply through lack of initiative is not clear but it is a fact that prior to the present ownership no “name” group or out of town band had been booked into the Station Inn. The move to 12th Avenue pretty well eliminated the college clientele and with essentially the same band playing six nights a week the crowds had dwindled to the point that a dozen paying customers seemed almost like a good night. J.T.’s friends privately feared he had bought a loser.

“Lance LeRoy and I talked about this a lot right after I took over,” J.T. says when reminded of those leaner days just a short while ago. “He manages the Bluegrass Cardinals and they were scheduled to play the Fan Fair celebration at Opryland that June [1981]. We worked out a deal for them to play here on a Wednesday night while they were in town and they packed it. They were the first name group to be formally booked in here and the very next week we had Country Gazette for two nights. They did equally well and since then we’ve had I don’t know who all. Just a partial list would include Bill Monroe, Buck White, Big Timber Bluegrass, Ralph Stanley, The Nashville Grass, Byron Berline, Randall Hylton & Morningtide and the Johnson Mountain Boys. The place only seats 140 at capacity and at times we’ve had to turn some people away because there wasn’t room to even stand any more.”

On an evening when an out of town band isn’t booked in, the entertainment might be provided by Red & Birdie Smith and The Blue Ribbon Band or by Nashville Skyline, which usually (but not always) includes J.T. Gray, guitar; Charlie Cushman, banjo; Stan Brown, bass and Gene Wooten, Dobro. Johnny Warren sometimes comes in and plays fiddle and Roland White often joins them on mandolin when he’s in town and not otherwise occupied.

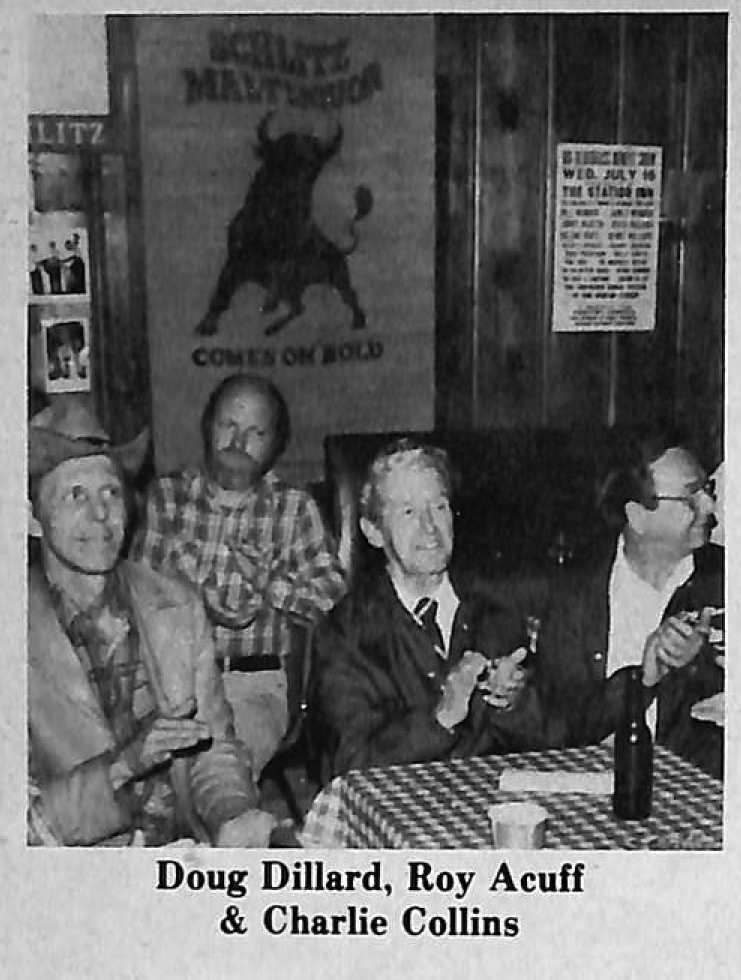

With Nashville being home base for such artists as Bill Monroe, Earl Scruggs, the Osbornes, Mac Wiseman, Wilma Lee Cooper, Jim & Jesse, Lonzo & Oscar, Jimmy Martin, Doug Dillard and others it’s understandable that the Station Inn’s friendly environment would attract a “who’s who” clientele with the result that the featured band is often joined later in the evening by the likes of Hoot Hester and Blaine Sprouse on fiddles; Jerry Douglas on Dobro and Steve Scruggs on banjo to randomly name just a few. This could happen only in Nashville, oddly enough the city where bluegrass is a veritable outcast among the “establishment.”

Recounting the main events that have taken place since he transformed the Station Inn into a bustling nightspot for hard core bluegrass fans, J.T. Gray remembers a lot of sleepless nights, trying to figure out which direction to go and a lot of working until 4:00 in the morning. He also recalls some lighter moments, such as the evening when Norman Blake was just about in the middle of his second set. A man appeared at the door and announced that a house was being moved down the street and that all cars parked out front would have to be relocated temporarily. The show stopped while patrons went out and cleared the street. “After about 30 minutes everybody got seated again and Norman went back to picking. It wasn’t so funny to start with but when it was all over we got a good laugh out of it.”

According to J.T., future plans call for “keepin’ on doin’ what we’re doin’ and just trying to make it better. We’ve printed some Station Inn T-shirts and caps. A company has been doing some recording with hopes of putting together a ‘Live at the Station Inn’ album someday, featuring various artists who’ve played here. Our audiences include just about everybody.

Some people bring their kids and we have grandparents. They’re all great people and a lot of ’em visit regularly. It’s not your ordinary type club. We get people from a hundred miles or more who come to see a certain group or just to enjoy a night of bluegrass,” he concludes. “We try especially hard to make out of town people welcome.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

We have UNBELIEVABLE memories of the Station Inn. Absolutely fabulous!!! Remember 30 years ago like it was yesterday when LeRoy Troy saved us a parking spot at the Inn.