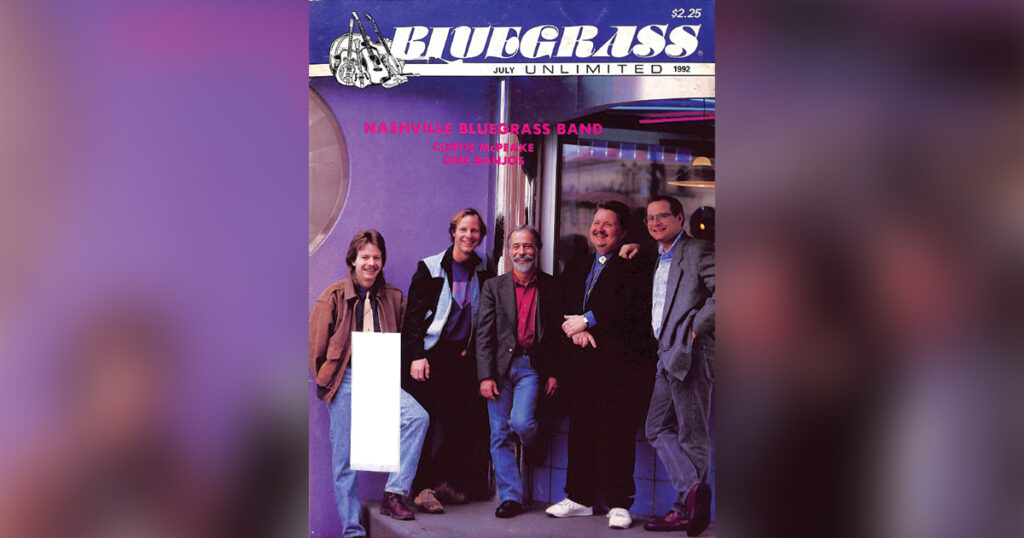

Home > Articles > The Archives > The Nashville Bluegrass Band—Reaching For The Gold!

The Nashville Bluegrass Band—Reaching For The Gold!

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July, 1992, Volume 27, Number 1

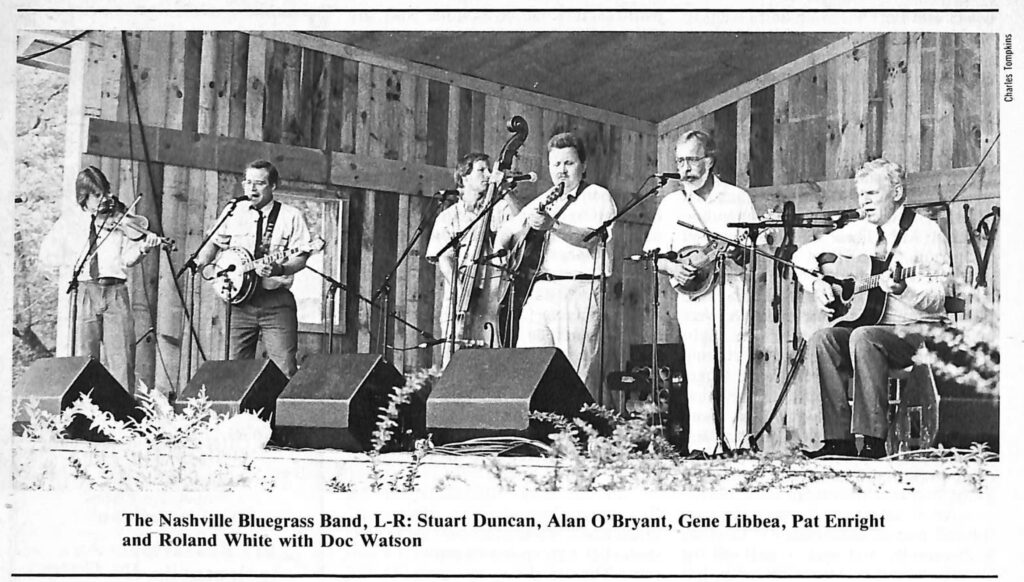

The Nashville Bluegrass Band is among the most exciting and highly acclaimed bands in bluegrass today. They have been the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Vocal Group Of The Year for two years straight (1990-91) and were 1991 finalists for Instrumental Group Of The Year and Entertainer Of The Year. They have received three Grammy final nominations. Their recordings consistently receive rave reviews and dominate the bluegrass radio charts. The band appears regularly on The Nashville Network, frequently guests on the Grand Ole Opry, has performed at Carnegie Hall and has toured internationally from Brazil to China.

Such credentials make it hard to believe that this band got its start almost by accident. In 1984 founder Alan O’Bryant had an attractive touring opportunity with a package show, but no band to fill the slot. He called some friends with whom he frequently picked informally at Nashville’s Station Inn Club and when they began rehearsing material for the tour, a magical sound was born. Realizing that something special was happening, Alan O’Bryant, Pat Enright, Mike Compton and Mark Hembree made a commitment to continue as a full-time band after the nine-week tour was over.

The four members came from very different backgrounds, yet shared a common vision of the new group identity they were striving for. The emerging Nashville Bluegrass Band sound was a solid return to traditional bluegrass, seasoned with elements of many other American music forms from old-time country to black gospel. This “new-traditional” approach gave the music new vitality and accessibility without compromising the integrity of its bluegrass roots. Pat Enright reflects, “We had no idea whether the approach we were taking would be something that would appeal to people. At that time, doing anything based on a traditional style was thought to be poison. ‘You have to be contemporary, you have to be progressive, you have to do this, you have to do that.’ That wasn’t for us. We didn’t budge from the original [approach]. We felt if we can’t do this to our satisfaction, then there’s no point in doing it. We couldn’t say it was honestly creative unless we were giving ourselves free rein. Now it seems very well accepted and it seems that the elements we were bringing back and the new things that we were trying to put into it seem to strike a respondent chord in a lot of people.

“[A signature sound] is something we wanted from the beginning—we wanted to be recognizable and not just to duplicate an earlier sound. We had an idea of what we wanted to sound like although it wasn’t verbalized. It’s the approach we take, it’s the sense of taste. There’s always a little bit of tension, a little bit of urgency, even on a slow ballad. It has a lot to do with where we’re playing on the beat, it has a lot to do with the dynamics that we use both as individuals and as a band. We’ve never liked a sound that’s cluttered. You hear that term, ‘hard- driving,’ which I just don’t want to be applied to us. Drive is important, but it’s just strictly a buzz word. We don’t want to nail anybody in the head. There’s a lot of subtleties involved and there’s a lot of really beautiful things you can do and still have that sense of urgency without having to hammer it into somebody’s head.”

A large part of the Nashville Bluegrass Band’s “new” approach is actually a revitalization of the same influences incorporated by Bill Monroe in his formative years, including old-time, early country, swing and especially the blues. With soulful songs like “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome,” “Rock Bottom Blues,” “Blue Train,” “Home Of The Blues” and “Mississippi River Blues,” NBB has become known for putting the blues back in bluegrass. Pat explains, “To me blues is one of the big parts of bluegrass that separates it or makes it a style. That’s one big part of [bluegrass] that went away, especially in the late ’70s. It’s one of those things that people eliminated. They said, ‘This blues stuff—that’s too intense for people. Let’s do something much smoother and lighter. Let’s take all the hard edges out.’ A lot of those things that were an integral part of bluegrass for me were just taken away. And I think when we got together, if there was anything that was understood, it was that we wanted to put some of those elements back. Where we play on the beat, for instance, the rhythm, the blues aspects of it—they had to come back before it was [musically] palatable to us.”

This emphasis on songs which strike a powerful emotional chord is probably a large part of the band’s broad appeal. Alan O’Bryant sites an example of the universal expressiveness of NBB’s music. “[When we were on tour] in Berne, Switzerland, there was a guy that spoke very broken English who came up to me [after the show] and said, ‘There is many blues in the sound of your band. Do you have these many blues?’ I had to think for a minute and I said, ‘Well no, not really, but everybody has blues and it’s been said that playing blues is a treatment, is a way to deal with your blues and share your blues.’ And he said, ‘I think it’s true.’ ”

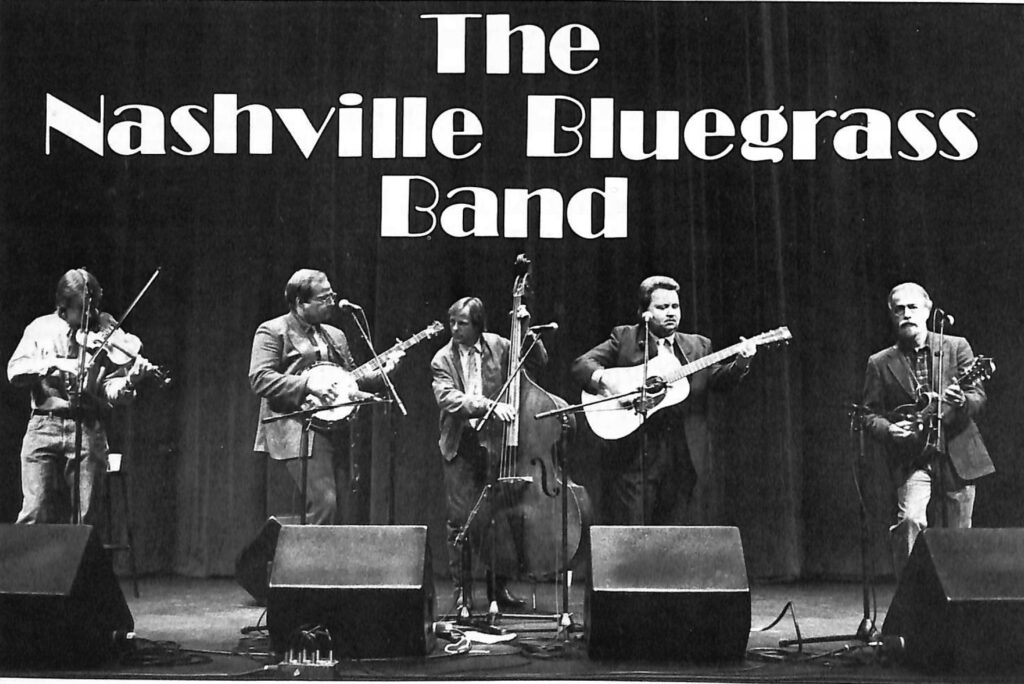

Though the band’s personnel has changed through its eight-year life (fiddler Stuart Duncan was added in the second year; Mike Compton and Mark Hembree were replaced by Roland White and Gene Libbea, respectively in 1989), the NBB signature sound has remained remarkably consistent. Alan stresses that, “The NBB sound is the combination of everybody’s idea of how the band should sound. The people that have come into the band since the formation have brought their own particular part of the sound with them.” Still, he reflects, “NBB is very ensemble-minded. That’s one of the things that I’ve admired about all of these guys in the years that I’ve worked with them. Everybody seems to put [the group sound] before their personal sound.” Pat adds, “We really try to listen to each other, we try to compliment each other as much as we can. But it’s difficult because we’re all real different from each other. We have different personalities, we come from different places, our musical and life experiences are vastly different. Vocally and instrumentally we have varying degrees of prowess and varying degrees of approach from the simple to the complex. You have to keep in mind when you’re playing with a group, there’s a certain part of your ego that has to be given up for [the group effort].”

The fact that there are no “egos” in this band is one of the things that makes NBB special and certainly has helped to insure the band’s survival through the years. The mutual cooperation, respect and admiration between its members is a recurring theme in any discussion about the band, with any band member. Alan voices the general sentiment, “This is a great bunch of guys to work with. I’ve always found them to be true gentlemen and good friends to me.” He continues, “Everybody has a particular responsibility or role to play in the physical logistics of making the band work.” Gene Libbea explains, “Everybody does have an assigned role in the band. Alan is the secretary/treasurer, Pat is the president, Stuart is the mercantile manager, I handle rehearsals and stage set-ups and Roland does the equipment managing.”

This democratic ethic is also evident in NBB’s stage shows. Song sets are carefully constructed in order to highlight each band member at some point during every show. Unlike many bands, who have only one or two members who are designated to talk on stage, on a given show every member of NBB is likely to take part in the MC work. This removes the burden from any particular person, increases rapport between the individuals in the band and the audience and makes the show feel more spontaneous and interesting.

Musically as well, Pat points out, “Everybody seems to have their little specialty in the band and everybody does it real well.” Gene elaborates, “Stuart on his fiddle has got his own world of sound to himself. Alan has a unique style of banjo playing. He has really got a nice feel, an old-timey feel. Roland White, he’s got his own style of mandolin playing, and night after night he’ll continue to amaze me. He’ll blast something out of that mandolin that I’ve never heard him do before. He doesn’t just swat the mandolin either. Roland plays a lot of two-note chords, a lot of thirds—a lot of his solos are based on thirds, two notes together—and very few mandolin players can do that. It takes some people a long time to notice Pat, but he has a great rhythm hand. He has the lightest touch I’ve ever seen on the rhythm guitar, and consistent—it’s always there, it’s always the same, and you can always count on it.”

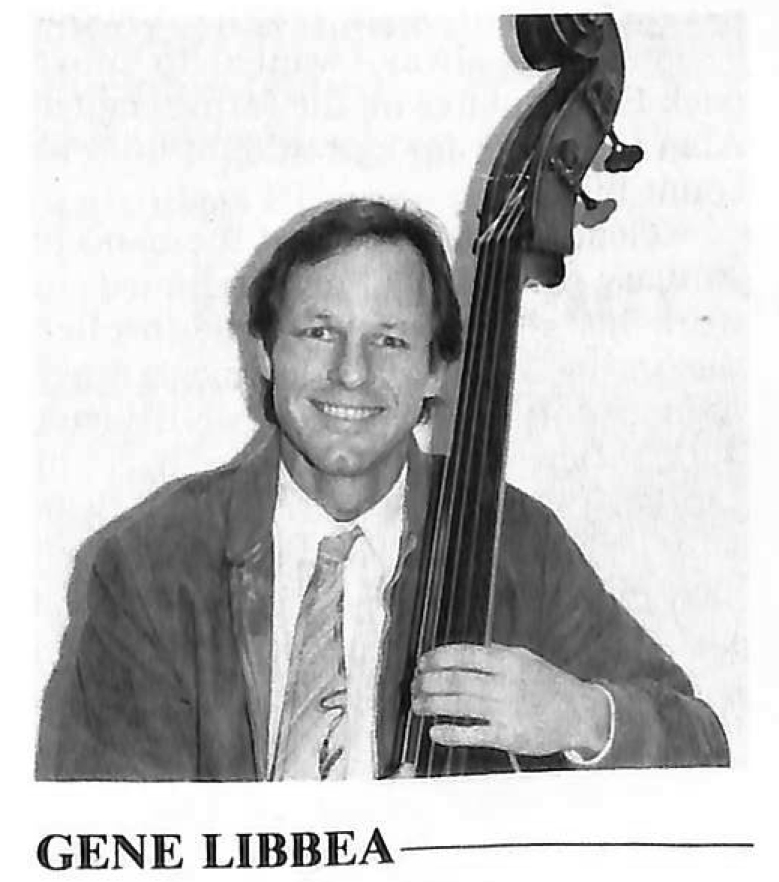

An integral part of the Nashville Bluegrass Band’s trademark sound is the emphasis on rhythm rather than “drive” as the backbone of their music. Alan notes that, “The rhythm and the feel of the song is the primary thing that we go for, and whatever happens melodically [happens] around that.” And quietly providing the foundation for that distinctive NBB rhythm are bassist Gene Libbea and guitarist Pat Enright. With his natural ear for bass notes and his broad musical background, Gene has a knack for playing exactly the right notes to fit a particular song. His playing is always tastefully creative, and his occasional stunning bass solos add a special excitement to live shows.

Though Pat’s guitar playing has a major impact on the NBB sound, he is modest about his contribution. “I try to fit in, try to keep up with the rest of them most of the time! I’ve never really thought I’d developed any kind of style. I consider what I play pretty much cut and dried bluegrass rhythm guitar playing. I use a minimum of runs and, my ability aside, most of that is due to the players in the band—it’s just not necessary. Everybody in this band is so rhythm-atuned. I try to play where it’s not going to be in anybody’s way. What I do is very simple, but I try to do it consistently and constantly. Alan and Stuart and Gene and Roland, they’ve all just got it. All the fills and all that, they can handle that. [My role is to] just keep it simple and consistent and allow the lead players to stretch out and feel reasonably sure that they can get out on a limb and the rhythm will still hold together.”

Having the opportunity to play in a band with such a solid rhythmic foundation has helped Stuart Duncan become one of the premier fiddle players in bluegrass and country music today. He has been named IBMA’s Fiddle Player of the Year for two years straight. His taste and creativity are unmatched, his solos are dazzling and his back-up always appropriate. Stuart is renowned for his ability to remain true to the melody while at the same time injecting the excitement of improvisation based in the feeling of the moment. During his tenure with NBB, he has become one of the most sought after studio players in Nashville, with a lengthy string of recording credits with everyone from Doc Watson and Peter Rowan to Dolly Parton, Don Williams, and Travis Tritt. Stuart feels that his wealth of studio experience has helped him contribute to the progress of the Nashville’ Bluegrass Band as well. “One thing I’ve gained from the large amount of studio playing I’ve done is a greater ability to make any improvising I do work for the tune as a whole—to base it on the melody. I try to apply that thinking to any setting. If there’s one thing that my presence adds to the group, it’s probably improvisation. It’s always been my way of reaching the audience—and it also keeps things close to the edge.”

If Stuart is NBB’s instrumental “star,” then Alan O’Bryant might be called the vocal “leader.” His crystal clear, soaring tenor harmony and high lead vocals are an immediately recognizable element of the group’s sound. His singing is both technically flawless and powerfully emotional. Like Stuart, Alan is highly recruited for studio work. He has harmonized on recordings by Doc Watson, Peter Rowan, Marty Stuart, John Starling, and many more, and is also frequently asked to sing on song demos (preliminary recordings of songs used by songwriters to present material to producers, artists, and publishers.)

Anyone who has seen the Nashville Bluegrass Band live has noticed Alan’s unusual practice of holding his banjo up near his vocal microphone when he is singing certain songs, so that he appears to be singing into the banjo head. Alan enjoys the mystique surrounding this habit, which always stimulates audience curiosity. “At some point I started picking the banjo up to get the weight of it off my diaphragm so I could have a little more [vocal] control to hit high notes,” he explains. “I noticed that when I would lift the banjo up high, when I was singing in the key that the banjo was tuned in, I could hear it resonate. It would resonate so completely that one of the strings would ring out in whatever overtone would come from where they were tuned. So I started using it, because you can sing into it and it will resonate and it’s almost like a reverb effect in the microphone. Really I guess part of the idea occurred to me just from a musical attitude of voices and strings vibrating together making a sound. People started asking me about it when I’d do it, and so of course I kept doing it. It’s kind of turned into a little trademark. I think it sounds neat when you can hear it, when the musical situation is right and the audience is quiet enough.

“Another thing that I’ve started doing is singing into the banjo during the a cappella songs to help stay in pitch. When there’s an acoustical problem in a room or with a sound system, or maybe somebody’s voice is tired, the principle tone will tend to shift. It will either come back to you a little bit flat or you’ll hear it a little flat or you’ll sing it a little flat. But if I sing into the banjo, it’s going to vibrate back to me true to where the banjo’s tuned, and so sometimes I can use it to help stay on pitch.” Can the other band members hear what Alan hears? “If the situation is right I’m sure they can hear it, but it probably doesn’t matter to them whether they hear it or not! They say, ‘Oh that’s just O’Banyon singing in his banjo again!”

Most of the band’s lead vocals are handled by Pat Enright, and together he and Alan harmonize like the best of the classic brother duets. Alan’s lilting, soulful tenor is the perfect complement to Pat’s rich, sure-footed lead. Pat reflects, “We do have a [special] sound when we sing and it’s amazing that it happens that way, because we’re two different kinds of people with two different approaches. When we sing together we try to find a common ground. We do work at it, and we’re conscious when we’re singing together that we want to make it work. People talk about ‘blend’ a lot, but blend can sometimes rhyme with ‘bland.’ We want it to be pleasing, but not blend so close that it’s not distinct, that you can’t hear what one or the other is doing.

“On the duets, nine times out of ten Alan’s going to sing tenor and I’m going to sing lead. He’s a tenor singer. He’s very versatile, very adept, and he can do all that sort of thing. Our latest album (“Home Of The Blues,” Sugar Hill 3793) has more duets than we’ve ever done [on an album]. It wasn’t conscious, the songs dictated how they came about. I’m glad we have a lot of duets on this album. It’s a freer form of harmony singing—the tenor especially has a lot more freedom—so it makes it more interesting and a lot more fun. You can get the feeling of the song better, especially some of the bluesy numbers, as a duet rather than smoothing it out as a trio.”

NBB does include plenty of trios in it’s repertoire, however, allowing Pat and Alan to show their great vocal versatility. On trios they frequently exchange parts, featuring Alan as lead singer and Pat in the tenor slot, while Stuart Duncan usually handles the baritone part. Gene and Roland join in on certain songs (especially gospel quartets or quintets) as well, providing a remarkable degree of variety in the vocal sound. Pat notes, “The fact that we’ve got more than one singer in the band helps a lot. It makes it more interesting for folks. Most bluegrass bands are built around one lead singer, one guy sings tenor, one guy sings baritone. No matter how good they are, after a while you want to hear something different. Not just a different singer singing the same type of song, a different singer singing a different type of song.”

Decisions about song selection and arrangements are made democratically. “When we work songs up we kind of let them develop naturally,” continues Pat. “We’ll take it slow and let it evolve. It’s a long process that everybody is involved in. It’s like creating anything—a sculpture—if you’ve got five different people working on a sculpture, the possibility of it turning out really weird is high! So you have to give and take and see what works best.”

Sometimes, as Alan points out, what works best may not be obvious initially. “I’ve always had a free and open opportunity to voice anything that I felt like musically needed to be a part of what we were doing. Sometimes it’s readily accepted and other times you kind of have to get in there and fight and scratch for something you want to do. I’ve always felt like I could do that if 1 had to. There’s been a couple of gospel songs—‘Rollin’ Through This Unfriendly World’—I remember having to really fight and scrap for that one. I think it’s a great song and I’m glad it’s part of our show now. ‘Home Of The Blues’ is another one. I could hear it immediately and I just fell in love with it. I said we’ve got to do it. I could always hear it in my head as a good duet—the blues aspect of it, the speed of it, I could hear Pat and me singing it. We never quite approached that the first few times that we [rehearsed] it and I think people [in the band] kind of got stymied on it, and it didn’t fare well in the voting as to what should be on the album. I remember lobbying real hard for ‘Home Of The Blues,’ because it was the last song on the list for the album, and at one point I even joked with somebody, saying, ‘You just watch, this is going to be the title song of the album!’ And it’s great. [We do it] better now than when we cut it. It’s one of my favorite songs that we do.”

How does NBB go about putting together an album? “We take a look at what we’ve got and start narrowing it down into what we think would fit together and be the most pleasurable,” says Alan. “We do make a conscious effort to make it- varied and to have something representative of different rhythm schemes, different keys. We want to try to have an instrumental, we want to try to have a couple of gospels, we do consciously try to go back and have what we call ‘an old chestnut’ or two on the album. And then we try to focus on the very best of as much new stuff as we can get our hands on.”

The band is pleased that the hard work that went into their newest release is being rewarded. “Each recording I’m involved with from start to finish seems like a year’s worth of studio education,” Stuart attests. It’s a good feeling to work on a project for that long and get the kind of response we’ve had from this album. I think ‘Home Of The Blues’ is the band’s best effort to date. Everybody was in good voice, good humor, and I think that feeling comes out in a recording. Working with Jerry Douglas was especially fun this time.” Alan agrees, “Jerry’s a great producer. He’s very experienced, he’s very knowledgeable and at home in the studio, and has a wonderful way of working with people to get a good performance out of them.”

Pat adds, “The production is real good. I really like the songs, I like the arrangements. We worked hard on those arrangements, because some of the songs are really coming from different places. Most of the [songs] we do, we really want to interpret as our own. Some of the material we bring in is pretty outside [of bluegrass] and a lot of people wouldn’t think about doing it. But if we can make it sound natural, then—Oh yeah, that’s a Nashville Bluegrass Band song.” A perfect example from the new album is “The Fool,” an old rock and roll song that Pat remembered from his youth. NBB’s bouncy rhythm and tight harmonies make this song sound like a bluegrass original. In the same way, Jimmie Rodgers’ “Mississippi River Blues” and Johnny Cash’s “Home Of The Blues” sound like they might have been written just for the group.

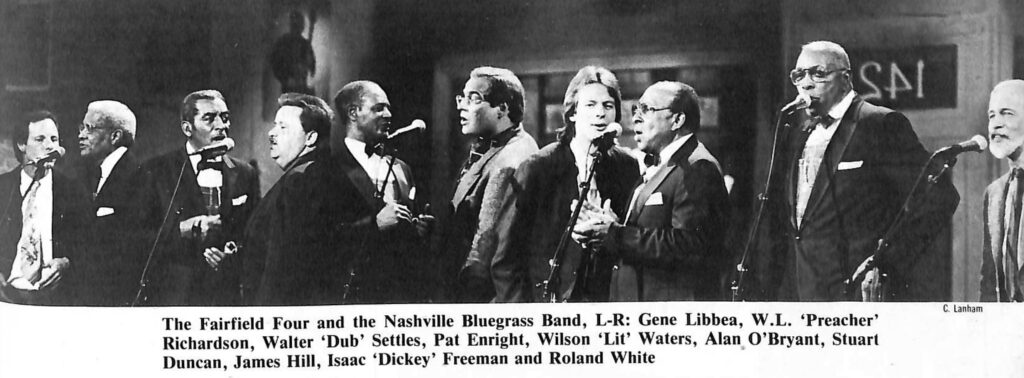

The Nashville Bluegrass Band’s most significant musical innovation is the inclusion in their repertoire of material adapted directly from traditional black gospel quartets. Though not the first bluegrass band to tap this incredibly rich source, NBB does so in a way that makes it accessible to the bluegrass audience while simultaneously maintaining the integrity and authenticity of its roots. In addition, NBB may lay claim to be the first bluegrass band to use five-part vocal harmony on some of these songs.

Pat states, “There’s always been a precedent for a cappella singing in bluegrass, it’s nothing new. But what we took it from was primarily the black church, [because] a lot of the material and the feeling from that [style] appealed more to us. When we first started out singing the a cappella stuff—which none of us had done much of—it was a slow process. The first song we worked up in that genre was ‘Blind Bartimus,’ and it was probably the most difficult one to do. We took it note by note.

“We feel [the a cappella material] fits very well with what we do. We don’t try to reproduce a sound, but we do try to reproduce the feel, because if we can’t get that feeling across there’s no reason to do it. We’re not trying to reproduce songs of a particular religion or race—if they’re good songs, they’re going to appeal to everybody. The bluegrass audiences that we play for are starting to recognize it as just part of what we do, and also have been turned on to a different kind of music. We always get a lot of [inquiries], ‘Where does this come from, where do you get this?’ To a lot of people it’s brand new. They’ve heard a cappella singing, they’ve heard bluegrass gospel singing—this is a different animal, and the way we do it is different. We’re less concerned with precise, stacked harmonies and more with the feeling and the kind of internal rhythm it has.” Growing out of their love of the a cappella style, the Nashville Bluegrass Band has recently begun to perform occasionally with gospel legends, the Fairfield Four. The two groups had the honor of performing together in April of 1991 as part of Carnegie Hall’s Centennial Celebration, and a studio version of the song they performed, “Roll Jordan,” is included on NBB’s “Home Of The Blues” recording. The same cut of “Roll Jordan” appears on the Fairfield Four’s new Warner Brothers recording, “Standing In The Safety Zone” (released in May, 1992), along with a brand new collaboration with the Nashville Bluegrass Band, called “The Last Month Of The Year.”

Pat explains how the relationship developed. “We had seen the Fairfield Four in Nashville on a couple of occasions. They’re without a doubt the best group performing that style [of music] today. The opportunity for us to perform with them came when they became affiliated with the same agency [that we are], Keith Case & Associates. We’ve worked some shows with them primarily for our audience. In a sense we’ve introduced them [to a new audience]. It’s really interesting to see the reaction. It’s just undeniable awe to hear these guys sing. They’re so powerful and they do it with such conviction. It’s been really good for us, and it’s also a way of showing people who ask where this style comes from—well, here it is. And the fact that we’re able to sing with them, and pull it off, to me is pretty amazing!”

Alan adds, “I know that any audience that’s ever come to see us will absolutely love the Fairfield Four. It’s real exciting for me to be able to bring those guys to a show that we’re on and to see people be able to hear and see and experience that part of our musical heritage as Americans for the first time. I just see people come away with their jaw dropped open and it tickles me. I really get a lot of satisfaction out of that because I know what it meant to me the first time that I heard them. I trembled for a couple of hours, and I just could not get over what I’d heard!”

Apparently their studio performance of “Roll Jordan” had the same effect on producer Jerry Douglas. Gene Libbea relates, “It was a live recording, all ten of us, all at the same time. I’ll never forget looking through the console window at Jerry Douglas when we finished the song. Jerry almost fell over in his chair! His eyes were rolled back in his head, pinned open, and his mouth was wide open. We did two takes and used the second take. It came out just spectacular!” Roland White agrees. “One of the things I really, really like about this album, as much as any album I’ve ever done, was that we had the Fairfield Four on it. What I learned from them was the same kind of thing I learned from being around Lester Flatt and Bill Monroe—that they’re not putting on, they’re just the real thing. ‘This is me, this is what I do, and I like doing it and this is how I do it.’ ”

The band has performed on even more shows with the Fairfield Four this year, even including a few festivals like the Merle Watson Festival. To complete the “cultural exchange,” the Nashville Bluegrass Band hopes to get the opportunity to take their own brand of NBB gospel to some black audiences in the future. Pat recalls, “On a couple of occasions we had a chance to play for a largely black audience, mostly by accident. The first was in Jackson, Miss., at a city-sponsored music festival with all kinds of stages. There was a lot of good music—a lot of blues, a lot of rock and roll. We did our bluegrass show, and they asked us to do a gospel show, which we don’t usually do. Well, we got to the gospel tent and the group on before us was a ninety-person choir from a black church, and the tent was rocking. We were scared to death, and I seriously wanted to say, ‘Let’s say we’re sick and go back to the hotel and hide.’ The minute we got on stage the tent started to empty. The sound was really horrible, the monitors didn’t work, and everything was against us. A few people came over from the bluegrass tent and they were there, but by and large the tent pretty much emptied out. We started in, and about ten minutes into it the tent started to fill up again, and about half way through it was full again! And they got into it like nobody’s business, and it was just as scary! And after the show we stood there at least an hour, talking to all those people from black churches that wanted us to come down and do a program. It was a really great experience for all of us, because it kind of [gave us] a stamp of approval that we felt we needed—that we can take a particular style and sell it to the people who originated it, without any prejudice involved at all.”

In addition to reaching new audiences at home, the Nashville Bluegrass Band is eager to take their music around the world. International touring is an important part of their long-range plan. “We’ve done some pretty amazing foreign touring, I think, for a band like us and people our age,” asserts Alan. “We were the first bluegrass band to play in the People’s Republic of China. In 1988 we were able to go to Japan, we did a European tour that took us to Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and France, and we were in the Middle East.” In 1990 NBB toured in England, and in 1991 they played at the huge Tundra Festival in Denmark, went to Brazil as part of a country package show including Don Williams, Asleep At The Wheel, Doug Kershaw, and others, and spent two weeks performing to sell-out crowds in Italy, Switzerland, and Germany.

Foreign touring brings the band not only new exposure, but personal enrichment and new friendships as well. “We like to listen to and experience as many different kinds of folk music, as we can,” Alan continues. “And an important revelation came out of all of this to us, that the further back you go into these traditional folk musics, the more you can draw similarities on them and you can strike a common tone. I guess the single most important thing that I’ve learned from the international travel that we’ve done is that music has the ability to transcend languages, socioeconomic background, race, creed, color, whatever. People can get together on listening to music.”

Another important way that the Nashville Bluegrass Band sees of reaching new people is television. The band recorded its first music video last fall, featuring “Blue Train,” from the “Home Of The Blues” album. The video began airing on TNN and CMT in January, and soon became one of CMT’s most requested songs. In addition to the video exposure, NBB has had repeated opportunities to appear on TNN in recent months, including features on Video Morning, Crook & Chase, Nashville Now, and performances on two different American Music Shop shows. NBB’s most significant television appearance to date was in May of this year, on the prime-time CBS-TV special celebrating the 25th Anniversary of the Country Music Foundation.

What does the future hold for the Nashville Bluegrass Band? “I’d like to see our interpretation of country/soul-grass reach a wider audience,’’ says Stuart Duncan. “That’s why we jumped at the chance to do our video. Television gets to places we’ll never go ourselves. Acoustic music is being recognized worldwide as a popular alternative to the forms of rock that have lost some people. I want as many people as possible to hear this band. I think if they enjoy listening to music they’ll like us.”

Alan adds, “Our most immediate goal would be to gain as much TV exposure as possible. [The video] is going to mean a lot to us because it is going to put us in the realm to move in the kind of circles that we think we ought to be moving in. It’s a great opportunity to get in front of a much larger audience.” He reflects, “I guess if I had a dream wish it would be that the Nashville Bluegrass Band could become a member of the Grand Ole Opry sometime in the next few years. We played the Opry about four or five times [in 1991], Being accepted in the country music community in Nashville and getting to play the Grand Ole Opry, the considered home of country music here in our home town—to be recognized by them and for them to have us on that many times in the year, to me is a real encouragement. I think that we could play an important role there, Nashville being our home, and the kind of music we play and the way that we combine it with old-time country music, I think we’d be real at home on the Grand Ole Opry.”

Roland declares, “I would like this band to be more popular than any band has ever been in bluegrass, to reach a real wide audience. We have good management, a good booking agent, a publicist, a music video, we’re doing lots of television, and that’s going to put us before millions of people. My goal is to be the most popular band ever in this style of music. I think Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs did that in their day, because they did a lot of television appearances, they played all the big shows, they had somebody who was behind them all the time, a lot of publicity. They had it, and they were ready when the opportunity came, they were prepared for it. And I think we are ready.”

Things are indeed falling into place for the Nashville Bluegrass Band. Their new “Home Of The Blues” album was a Grammy finalist and is receiving unanimous acclaim, their first video is receiving heavy airplay, and they have a crack team of booking/management, publicity, and record label personnel supporting them. “This will be the largest organized approach at promoting this band and a product of this band to date,” observes Alan. “Having all these things happen simultaneously will combine to raise the overall awareness of the band. This is really a long-term goal, and we’re reaching for it. That’s one aspect of the Nashville Bluegrass Band that’s exciting for me at this point. That we’ve been able to do it for eight years now, and that at this point in time we’re able to make this step to achieve a long-term goal that we’ve been working at for all these years—to me that’s exciting. I pinch myself everyday!”

Banjo player Alan O’Bryant grew up in the heart of “bluegrass country,” just a few miles from Carlton Haney’s legendary Camp Spring, N.C., festival grounds. There were plenty of bluegrass and old-time pickers in the area, and by the time he was in junior high school Alan was playing regularly with several different groups.

Alan often played music with his cousins, Billy and Terry Smith, and their father. He recalls going to his first bluegrass festival with them when he was fourteen (1970). “I went to my first bluegrass festival with my banjo, the clothes I was wearing, my cowboy hat, and like $2.76 in my pocket. I spent the whole weekend there and it was a dream world for me. I met Carlton Haney through my cousins. He was aware of us and our band. I was probably hanging around the stage and Carlton announced that they were going to have the ‘bluegrass orchestra.’ And he put me on stage with the ‘bluegrass orchestra.’ I can remember turning around and asking somebody like Sonny Osborne what key it was going to be in. I believe that was the first time I was ever on stage.”

Alan, Billy and Terry moved to Nashville in 1974 and continued to play together. A year later Alan went to work with James Monroe and the Midnight Ramblers, and he spent the next four years as an integral part of the Monroe entourage. He views that time as one of the most important learning periods in his musical development. “I got to spend a lot of time around Bill [Monroe] at what I consider to be an important time in his career. He wrote a lot of great songs during that time. I can remember seeing how he handled working on the road, how he handled his business, what it was like to play in different parts of the country, how it had to be done. I got to fill in whenever Bill was between banjo players, so I got to play with him some. We traveled with Bill quite a bit, so I got to sit up with him at night on the bus.”

Perhaps inspired by Monroe, Alan began to develop his songwriting skills as well during this period. “When I was with James Monroe I wrote ‘Those Memories Of You.’ Bill and James cut it on an album called ‘Together Again,’ on MCA (MCA 2367, 1973). That was pretty exciting for me because I’d never had a song cut, I didn’t know what publishing was, I didn’t know what songwriter royalties was, or anything else. Bill did publish that song, and it was later recorded by The Trio [Emmylou Harris, Linda Ronstadt, Dolly Parton] (Warner Bros. 25491, 1987) and was a Top 5 country single, which in the realm of music business changed my life forever.”

During his time with Monroe, Alan also became known as an excellent tenor singer, and he began to receive studio work. Such recordings as John Starling’s “Waitin’ On A Southern Train” (Sugar Hill 3724; 1982), which also includes Alan’s “Those Memories Of You,” show his emerging talent for perfectly complementing other singers. His harmony is exciting yet tasteful, always enhancing, never overpowering.

After leaving James Monroe’s band, Alan did stints in the Front Porch String Band, with Claire Lynch, and the Bluegrass Band, with banjo player Butch Robins, whom Alan knew from the Monroe years. The Bluegrass Band, which also included fiddle player Blaine Sprouse, blazed onto the scene, recorded one album (originally Voyager 330, now reissued as Hay Holler Harvest 100), toured for a season, but was forced to disband when its corporate underwriting ceased.

“There was some work that sort of spilled over from that band. It was a tour that this guy Geoff Berne had been trying to put together for a couple of years, and he finally got it together [in 1984], It was a country music package show with Steve Young, Vernon Oxford, a couple of New York bands, a dance troup, and a bluegrass band—us.” Berne called Alan and he set about putting together a new band for the tour. “That was more or less the basis for [The Nashville Bluegrass Band] getting started; we had work, but no band. It was a nine-week tour, it was lucrative, and we decided that we would get the band together and go and work the tour, and that while we were getting ready for the tour we would try and see if we could get this band off the ground. And we just went from there.”

Nashville Bluegrass Band guitarist Pat Enright grew up in Huntington, Ind. He became interested in music while in high school, during the folk music boom of the early ’60s. “I started going to some of the coffee houses in the area, and buying records. I got a guitar my senior year in high school, but I didn’t learn one song, and not too many more chords. I just had it, but never thought about it at all.” In 1969 Pat was drafted into the Navy, and was stationed in Washington, D.C. He became friends with another recruit who played the banjo and they soon discovered the fertile D.C. area bluegrass scene. “Every Tuesday night I could get off we’d go down to see the Country Gentlemen at the Shamrock Club. We went to a couple of the folk festivals; I saw Bill Monroe for the first time at a folk festival.” It was during this time that Pat developed a serious interest in playing music himself.

After finishing his time in the Navy, Pat moved to California. He soon met other Bay area pickers, including Laurie Lewis, and they formed a band called the Phantoms Of The Opry. “We were working all kinds of places along the West Coast. I was really taken with it—I liked the people, I just liked the whole life. It was fun, and after four years in the Navy I was really looking for a little life, rather than just go out and get a job. We got to be pretty good—we were a great bar band, and had a real eclectic repertoire. Early on I got into being as eclectic as I wanted to be—I did a lot of Hank Williams songs and country stuff—but I was also very traditional minded. The best bluegrass I’d heard was the first bluegrass I heard—like Flatt & Scruggs—and I didn’t want to get too far away from that. We came back East one year and played the Bean Blossom band contest and won, and really ticked a lot of people off because we had long hair, ponytails, we were ‘freaks’ from California and we played better than anybody else!” Eager to be closer to the source, Pat headed for Nashville in the mid-’70s. He was working in George Gruhn’s guitar shop in 1978 when he received a call from Jack Tottle of the New England band, Tasty Licks. “They needed a guitar player and tenor singer, and for some reason I was just ready to do it, so I moved up there and played with them a year. Bela Fleck was in the band, it was his first band—he was still a teenager. I made one album with them, called ‘Anchored To The Shore’ (Rounder 0120, 1979). I got a good taste of hard-core touring with that band.”

Pat returned to Nashville in 1979. After setting his musical career aside for several years, he began to participate in the blossoming acoustic music scene at the Station Inn. Great musicians who normally did not perform together would gather at the Station Inn when they were not touring, resulting in informal “jam sessions” which were often better and more exciting than a regular band performance. One group who began to jam regularly together included Pat on guitar, Jerry Douglas on dobro, Bela Fleck on banjo, Blaine Sprouse on fiddle, Roland White on mandolin, and Mark Hembree on bass. This incredible “pick-up” band began calling themselves the Dreadful Snakes. From the beginning they packed the Station Inn each time they played, and soon they were in the studio, recording “Snakes Alive” for Rounder Records (Rounder 0177, 1984).

Pat reflects that, “The Dreadful Snakes’ album probably did me more good than anything else, as far as getting my name out there. It introduced me to the bluegrass audience because all these players’ that had names were on it, and it was a good album. It was a lot of fun to do and there’s some good music on it. That kind of helped me get back in there and rekindled my interest. I still wasn’t doing anything professionally until this [NBB] opportunity came. When this came, I dumped everything and have stayed away from ‘day jobs’ since then!

“We’d all had various experiences in various kinds of bands, full-time, part-time. We said if we’re going to do this then we should do it whole heartedly, do it full-time, and put what needs to be put into it. And we did that, and we suffered for it. In the first years this band worked incredibly hard. I didn’t make enough money to put gas in most people’s gas tanks. But we stuck with it, and it worked out.”

As far back as he can remember, music has been a part of Californian Stuart Duncan’s life. “Some of the first music I heard was my dad playing banjo, clawhammer style, with some friends. My mom played a little guitar and sang some folk music, too—Irish ballads, Scottish ballads. My first exposure to bluegrass music was in southern California in the early ’70s at a folk club called In The Alley, where my dad ran the sound system. The first fiddle players I saw there were Byron Berline with The Dillards and Vassar Clements with the Earl Scruggs Revue.”

Inspired by what he had seen, Stuart got his first fiddle at age seven. After a year of lessons he began playing with bands in the San Diego area. ‘‘My first band was the Pendleton Pickers. We were ‘cute,’ and before it was over we were potty-trained and had appeared on the Grand Ole Opry! The first ‘large’ memory [of a musical accomplishment] I have was winning a Friday night spot on the Grand Ole Opry with the Pendleton Pickers in 1974. It was [first prize in] a KSON (San Diego) Radio band talent contest.” Stuart remembers the thrill of getting to meet the Opry stars backstage. ‘‘Billy Walker introduced us, I met Lester Flatt, I saw Marty Robbins, and Jimmy Martin tried to kiss me.”

Just prior to that, Stuart had played his first major bluegrass festival with the Pendleton Pickers, and had seen many of the legends of bluegrass for the first time. “1974 at the Golden West Bluegrass Festival in Norco, Cal., was the first time I’d seen Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt—Marty Stuart was with him, Ralph Stanley—with Roy Lee Centers and Keith Whitley, Jimmy Martin—all at one festival. That was also the first time I met Pat Enright. He was with a band called the Phantoms Of The Opry. that played that festival.”

By the time he was twelve, Stuart had met a young banjo prodigy named Alison Brown. They performed together in a band called Gold Rush and also worked as a duet, voraciously exploring new bluegrass horizons. “The next big thing that happened was my dad took me on a summer tour of bluegrass festivals when I was twelve, in 1976. He would say, ‘O.K., where do you want to go next,’ and I told him, and that’s where we went, for about six months. Then Alison and I did the same thing two years later with my dad. So those two years stand out as very memorable, formative years.” In 1980 Stuart and Alison recorded an album entitled “Pre-sequel” for Ridge Runner Records (RRR 0030) (among the supporting musicians on the album were Gene and Steve Libbea, whom Stuart met in the late ’70s). Stuart reflects, “With our ‘madness’ and ‘teen wit,’ Alison and I were constantly refurbishing and often destroying old bluegrass ‘evergreens.’ I look at those years as a very formative time in my musical development.”

Soon, however, Stuart’s taste began to swing back toward traditional bluegrass. “After hearing the old tapes of Monroe, Stanleys, Flatt and Scruggs again, I began to feel that the 16th notes weren’t getting me to the end of my solos any faster. In 1981 I began playing with a more old-timey bluegrass group called Lost Highway.” After three years of touring with Lost Highway, interrupted by a year of studies at South Plains College, in Levelland, Tex., Stuart found himself back in California, “playing ‘Elvira’ in a country bar. A phone call from Larry Sparks in 1984 got me and my truck out of there, and I was on the road again. I had met him when he came to California in ’83. I was off the road from playing with Lost Highway that winter, and Pat Brier and Nick Haney and I opened up for Larry at a show, and we played a little backstage. His mandolin player quit a few months later, and that’s when he called me, and I just packed up and moved. Working with Larry was a soulful, rhythmic experience, and the closest thing to a day job I had known so far.”

After a year with Sparks, Stuart began to get the urge to spread his musical wings again. “By 1985 I was feeling like I had maybe left too many 16th notes behind. Two shows with Peter Rowan and Crucial Country took care of that. With the urging of Bela Fleck and many others, I left Lexington, Ky., for Nashville. For a few months I worked some with Roland White at the Station Inn. In the spring of ’85, after playing a few informal shows with them, I took the empty stage-right position with the Nashville Bluegrass Band.

“My attraction to this band was immediate. Here were four semiliterate guys that weren’t afraid to sing old-time duets—and brand new songs. They weren’t scared of the blues or black spirituals. The accompaniment was tasteful and sparce, leaving me plenty of room to search for those lost 16th notes. Not just another bluegrass band!”

Mandolinist Roland White was born in Maine, the oldest of four children in a musical family. “My dad played guitar, sometimes he’d play banjo, most of the time he played fiddle. It wasn’t bluegrass music, it was what was popular in country music at the time. They were French Canadians and he did a lot of French Canadian things on the fiddle—Irish jigs he called them—and once in a while somebody would dance. I started playing guitar around home with my dad when I was five, six, seven years old. He showed me some simple chords, and by the time I was ten years old I was doing more. And my brother Clarence was able to play a little bit of guitar, and I had a couple of harmonicas. By the time we moved to California in 1954, my sister Joanne was singing and we started playing talent contests.”

By this time Roland was also learning to play mandolin. His uncle told him about a mandolin player named Bill Monroe who played on the Grand Ole Opry, and Roland ordered a couple of Monroe’s records from a local music store. “His mandolin playing got my attention right away. It was quicker than what we played—it was very different. Everything was a little faster tempo. The first time I saw Bill Monroe was in 1956 on Town Hall Party, which was a great big country music [television] show. They had guests from the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday night, and Bill Monroe was one. We couldn’t go because it was sold out, so we watched it on TV. It was Christmas Eve, and my dad and I had bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder that we could record our music on. So we recorded that concert off the TV set. I saw Bill live for the first time about two years later. We met him, and he had us all get up on stage and play their instruments—which was difficult. [After that] they had an open invitation to come to our house when they were in town. My mother would always have a big dinner for them whenever they came out.”

By the late 1950s the White brothers (Roland, Clarence, and younger brother Eric) had met a hot banjo player named Billy Ray Latham, and they began to play bluegrass, calling themselves the Country Boys. “In 1960 our career really got a boost because the folk music scene was pretty big and we were getting a lot of work in Southern California in colleges and folk music clubs. Ash Grove was one. I think we were the first bluegrass band to play there, and then he got Bill Monroe, and he got the Stanleys, and he finally was able to get Flatt and Scruggs when they came out there. That’s about the time that they got the Beverly Hillbillies deal.”

In 1960 the Country Boys got a call from a booking agent friend who had a television opportunity for them. He had received an inquiry from the producers of The Andy Griffith Show, who wanted a “folk band, on the country side” to appear in an episode of the show. When the Country Boys arrived at the studio, Andy Griffith told them which songs he had chosen, rehearsed the songs once with them, and they filmed the show. Classic footage of 23-year-old Roland, along with Clarence, Eric, Billy Ray Latham, and LeRoy McNees can still be seen in reruns of “Mayberry On Record,” which first aired in February of 1961. The Country Boys also appeared very briefly in a second episode, “Quiet Sam,” which aired in May, 1961. It is likely that they would have continued to appear in later episodes, had Roland not been drafted into the army that year. Instead another budding California bluegrass band stepped in: the Dillards made their debut in March of 1963 as the “Darling” family, and were featured in five more episodes over the next three years.

Eric White left the band in 1961 and was replaced by Roger Bush. While Roland was in the army the band landed its first recording deal, on Paul Cohen’s Briar Records, and picked a new name, the Kentucky Colonels. Roland returned from his army stint in 1963 and the-band made several East Coast tours (including an appearance at the Newport Folk Festival) before breaking up in 1966. Unfortunately, there were very few studio recordings made to document the legacy of this phenomenal, groundbreaking band, however several recordings taken from live shows surfaced in the mid-’70s, including “The Kentucky Colonels 1965-66” (Rounder 0070) and “Livin’ In The Past” (Briar 7202). In 1991 Vanguard Records released a CD of previously unissued Kentucky Colonels’ tracks from the Newport Folk Festival called “Long Journey Home” (VCD 77004).

Following the Colonels’ break-up, Clarence White joined the Byrds and Roland continued to play bluegrass around the Los Angeles area. The next year. Bill Monroe returned to California and this time Roland followed him back to Nashville, replacing the departing Doug Green as guitar player for the Blue Grass Boys. “I got the job, I came to Tennessee in 1967, and I’m still here! I worked for Bill for a year and eight months, and then in ’69 Lester and Earl broke up and I went to work with Lester Flatt until 1973.”

By 1973, Clarence White had left the Byrds, and the brothers decided to get back together. They did a European tour during which they recorded “The White Brothers (the New Kentucky Colonels)” (Rounder 0073, 1976). “We came back to the states and played the first and last bluegrass festival Clarence ever played, at Indian Springs, Md. Then I just commuted back and forth to California. We started to do some stuff for Clarence’s album, we did some TV, like the Bob Baxter show. Then one night we were up in Lancaster—that’s the night Clarence was killed [by a car], coming out of the club. That very week, Roger Bush [of Country Gazette] told me that Kenny Wertz was leaving their band and they needed a guitar player, and what was I going to be doing? We talked about it and I joined the band right away, and was with them until 1987.” After leaving Country Gazette, Roland played independently in clubs in Nashville, and was a part of the Dreadful Snakes recording with Pat Enright. After about a year and a half, he began to feel the urge to return to playing full-time, and when he heard that Mike Compton had left the Nashville Bluegrass Band, he called Alan O’Bryant to express his interest in the job. Alan called back and invited him to attend an upcoming band meeting and rehersal. At that meeting Roland became a member of NBB, and his first show with the band was at the SPBGMA Convention in February of 1989.

Like Stuart Duncan, NBB bass player Gene Libbea grew up in southern California and was surrounded by music. “There was always music around the house. My mother played piano and some xylophone and my father played a little drums, and the three boys, we all played drums in school bands.” In the early 1960s Gene’s older brother, Steve, began playing in local rock and roll and surf music bands. Gene was inspired to learn to play piano and soon began performing with Steve.

In the late ’60s Steve and Gene began to frequent a folk club in Redondo Beach called the House of the Rising Sun, where they first saw bluegrass artists like Byron Berline and Richard Greene. “My brother and a friend started playing folk and bluegrass sort of stuff, and one day at a party this guy brought a bass, and I asked him if I could try it. I had been thinking about renting a bass just to try it, because I had always heard bass notes; I’d always ‘thought’ bass. I tried his bass and a week later I bought it from him.”

In the early ’70s, Gene had his first introductions to “serious” bluegrass. “My brother and his friends said, ‘Let’s go up to this public TV station. They’re doing a taping of Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys.’ We got up there and they announced that Bill’s bus had broken down, and so ‘we have another band we’d like to introduce to you: The Muleskinner Band,’ which was Bill Keith [on banjo], Richard Greene [on fiddle], Stu Shulman on bass, Peter Rowan on guitar and vocals, Clarence White on guitar, and David Grisman on mandolin. That really opened my eyes up, to see a modern approach to this old style of music. That was the first time I’d seen really good [bluegrass] players playing together. I couldn’t believe it—it was great!

Soon after that, Gene experienced great “hard-core” traditional bluegrass for the first time. “I’ll never forget this. I had been playing bluegrass for about a year or two, and I got this call from Byron Berline. He said, ‘Hey, you want a gig, Gene?’ I said, ‘Sure.’ He said, ‘It’s this weekend out at Magic Mountain [theme park]. There’s this band called Vern and Ray.’ I thought to myself, ‘Who is Vernon Ray?’ After an explanation from Byron, Gene called Vern Williams and arranged to meet him, Ray Parks, and banjo player, Dennis Coats, at their hotel room to rehearse before the first show. “They said, ‘Well, what do you know?’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t know that many songs.’ Vern said, ‘Well, let’s try this one. It’s called “Ruby.”’ And Vern Williams opened his mouth and this glass-shattering voice came out, and I almost fell over with my bass! I was just floored. It was an incredible gig, and I played three nights with those guys. That was another high point in my early musical career.”

Throughout the ’70s, Gene and Steve played together in various bands in the blossoming California acoustic music scene. During this time they played and recorded with Stuart Duncan and Alison Brown, performed with the Sweethearts Of The Rodeo, and formed a band with Vince Gill and John Hickman. During the late ’70s, Gene and Steve made several extended trips to Europe, touring with a bluegrass band called Truckee. On one of these trips they recorded an album, on another they became affiliated with Club Med and worked at various European resorts for about a year. “They fed us, put us up—they didn’t pay us anything, but we had the time of our lives!”

On returning to the states, the Libbea brothers had an offer to play at Disneyworld in Florida. “We did that for an entire summer, with Craig Smith [on banjo], Barry Soloman on guitar, Dennis Fetchet on fiddle, Steve on mandolin, and myself on bass. We were called Backwoods. We worked an entire summer, eight-sets-a-day, six-days-a-week, in the blazing sun, with no PA [system]. We learned how to sing loud, we learned how to play hard and fast, and when we came back to L.A., we blasted into town. We played at a place called The Banjo Cafe, and we just blew minds, because we had so much energy and were so tight. I think that one Disneyworld gig had a lot to do with just getting my chops down.”

By the early ’80s, Gene had decided to return to school for a degree in aircraft mechanics. Upon graduating Gene went to work for American Airlines at LAX Airport, and about that time Steve moved to Nashville to pursue a songwriting career. Tragically, three days after he arrived in Nashville, Steve was killed in a small plane crash. Gene spent the next several years primarily working at his “day job,” but continued to play music occasionally around the Los Angeles area.

Then one night in 1988, his old friend, Stuart Duncan, called to say that the Nashville Bluegrass Band needed a bass player. Gene was tempted by the offer, but reluctant to leave his steady, well-paying airline job behind. He told Stuart no, and the band hired Californian Nick Haney. Gene and his wife Cheryl spent that summer at their farm in northern Virginia, and one night they drove to The Birchmere to see the Nashville Bluegrass Band perform. Though Gene had heard great things about the band, he had never seen them perform or even heard their recordings. “I about died. I thought, ‘I turned this down?’ Nick Haney was playing bass and all the time I’m thinking, ‘God, I wish I was playing bass!”

A few months later Nick Haney became ill and was unable to continue in the band. Stuart called Gene to see if he was available to fill in on a three-week West Coast tour in October. Gene arranged with his boss to have the time off and met the band in Portland, Oreg. After the tour, he agreed to play several additional dates with the band in January, but remained noncommittal. “About a week later I got to thinking, this opportunity is going to slide right through my fingers if I balk. We thought real hard about it, and we’d always wanted to move back East and live on the farm. I called Alan O’Bryant up and said, ‘I’ll do it; count me in!’”

Gene officially joined the band in January of 1989, but continued to work his airline job as well, through the spring. “My boss let me arrange my schedule around the gigs NBB had, and I flew to all the gigs, free of charge. I’d step off the plane back in L.A., and I’d go right to work. I’d have my tools in my locker, and I’d just pull those out and put my bass in the locker. Then in April we loaded up the truck and headed East.”

Penny Parsons served as Marketing and Promotions Director of Sugar Hill Records in Durham, N.C. for eleven years. In November, 1991 she formed The Penny Parsons Company, specializing in music industry public relations.