Home > Articles > The Archives > The Louvin Brothers

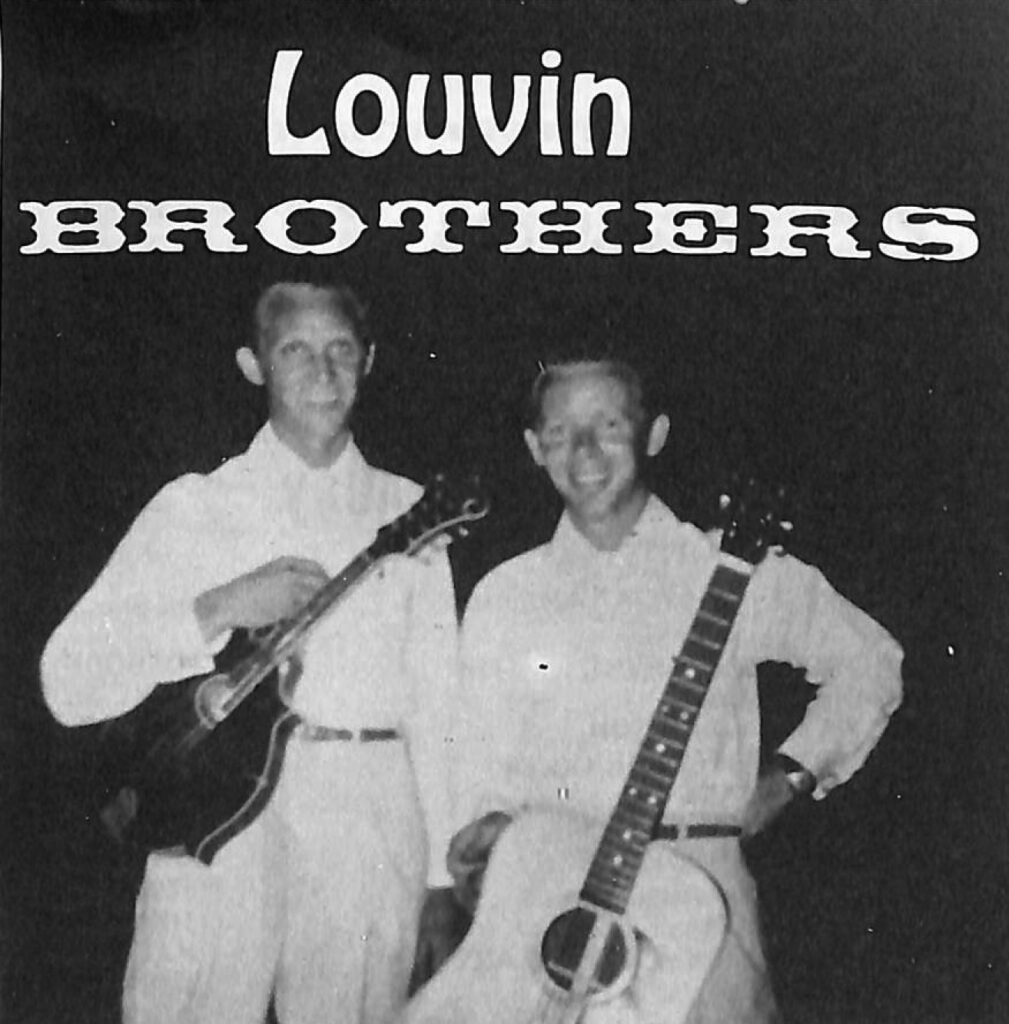

The Louvin Brothers

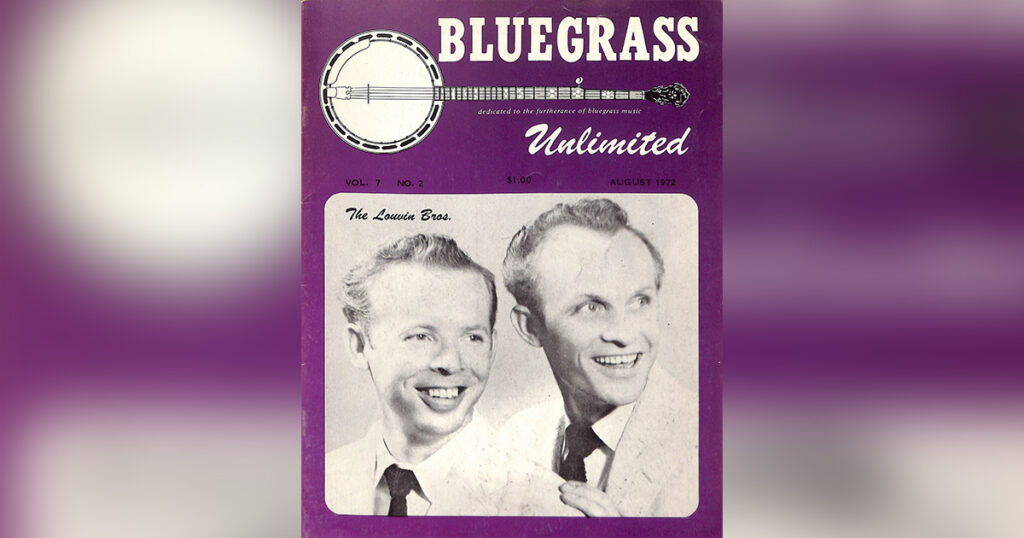

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1972—Volume 7, Number 2

I. Why The Louvin Brothers?

Not only because they played with a full bluegrass band for a year, and not only because of their deep roots in old-time duet singing, but because of the firm impression their songs and style have had on bluegrass music. They are an influential non-bluegrass band from which bluegrass has drawn some roots.

II. Their Story

Their story begins in a rural farmhouse in Henegar, Alabama, where Ira was born April 21, 1924, and Charlie July 7, 1927. The few idle moments on this poor Alabama farm were spent singing as Mr. Loudermilk played his banjo, or listening to the radio, absorbing the music of the Monroe Brothers, the Delmore Brothers, Karl and Harty, and most important, the Blue Sky Boys.

Ira and Charlie Loudermilk began singing together from their earliest memory, using and adapting the close harmonies they learned over the radio. “We sang at every cakewalk, ice cream supper, or anything else anybody had to offer,” Charlie recalls, “for free.” He remembers well the first time they were paid for their music: the Fourth of July, 1941, at Flat Rock, Alabama, aboard a “Flying Jenny”, a homespun, mule driven merry-go-round. They sang two songs “Hole in the Bottom of the Sea” and “I’ll Be All Smiles Tonight”

with a guitar playing friend (neither played an instrument at that time), and when these songs were done, the ride would be over, and a new load of riders would get on. For their eight hours of labor that day, they took home all of $2.00 each.

This and other appearances gave them a taste of making money for playing music, and this appetite was further whetted by local appearances of Opry entertainers such as Roy Acuff. “I wouldn’t lie to you,” says Charlie, “We were hunting something easier than the cottonpatch and cane field.”

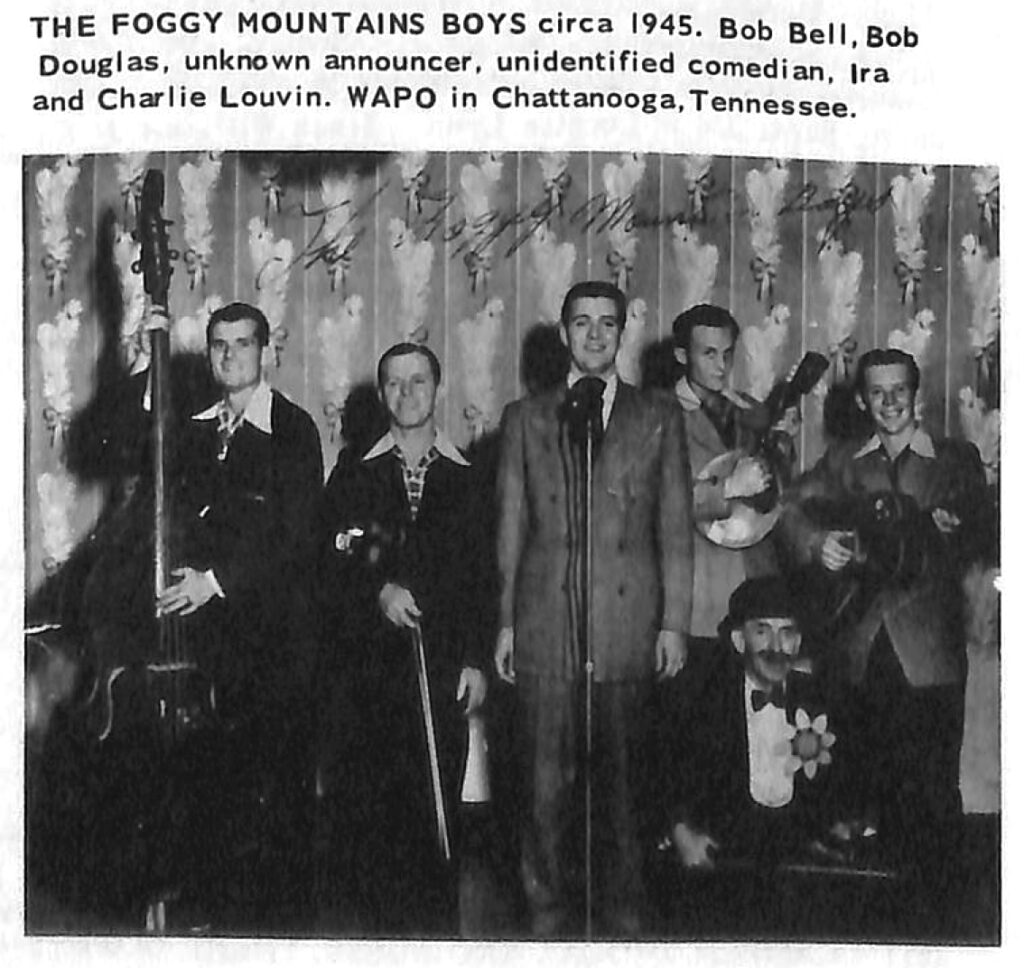

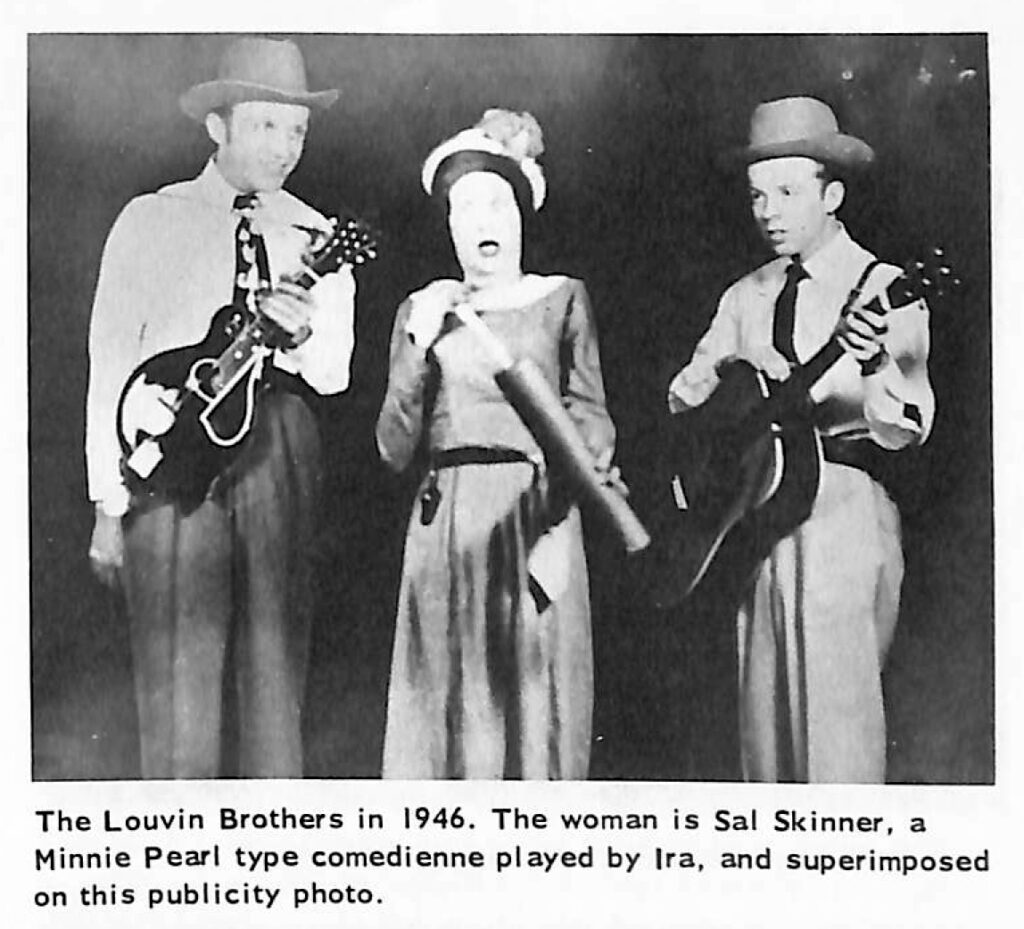

In 1943 the two boys left their parents’ farm and moved to Chattanooga, where they found work in a cottonmill. They were persuaded to enter a contest there, first prize being a 4:30-4:45 AM program on a 250 watt radio station. Two friends, Bob Douglas and Bob Bell, gave them the $5.00 entrance fee-and Ira and Charlie won it. The show led to a good many local bookings, and they soon felt that they were able to leave their day jobs. Known by the name “Foggy Mountain Boys” (a band which included both Douglas and Bell), they soon played out their immediate listening area, as so often happened on local radio, and when their bookings began to become infrequent, Charlie found it impossible to find a job because of his age-he had turned 18 and was draftable. Rather than fight the inevitable, he joined the Army, and returned in 1946 to find Ira in Knoxville, playing mandolin for Charlie Monroe. Oddly enough, since Charlie Monroe had a good tenor singer, Ira, who was one of the great natural tenors, was singing bass for the Kentucky Partners!

The two brothers soon re-formed their own group, finally choosing the name Louvin Brothers. “Before this,” says Charlie, “we just called ourselves names like the “Sand Mountain Playboys,” and we had some twin names worked up

we looked about as much like twins as Mutt and Jeff but we finally decided that Loudermilk was a little too hard for people to spell, ‘cause nobody could spell it right, and the name Louvin was picked. And it’s even harder to spell!”

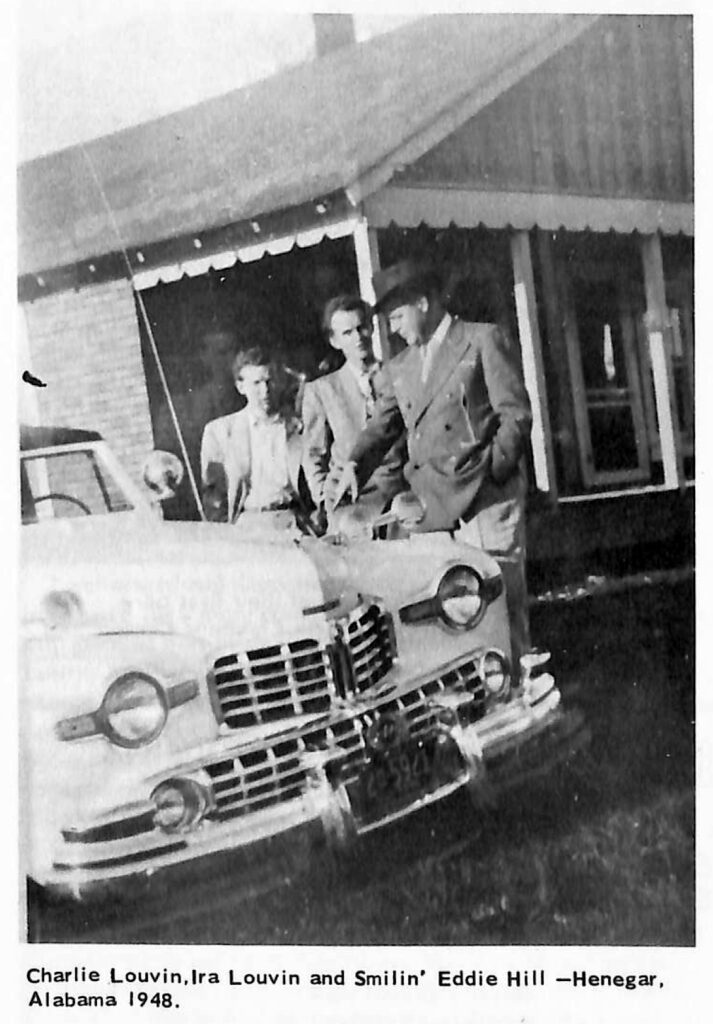

The Louvin Brothers, who were singing only sacred songs at that times, were working on the Cas Walker show in Knoxville, when Smiling Eddie Hill walked into their lives, with a borrowed suit, a borrowed car, a smooth line and grandiose plans. He talked them into moving to Memphis, where, according to Charlie, “we did quite well but a lot better for Eddie than for the Louvin Brothers.” Hill did, however, get their first songs published with Acuff-Rose among them some of the Louvin classics “Weapon of Prayer”, “Seven Year

Blues”, “Alabama”, and “When I Stop Dreaming.”

They left Memphis for a time in 1951, moving first back to Knoxville, then Greensboro, North Carolina, and finally Danville, Virginia, where they tried out a new sound that fitted their singing well bluegrass. They carried a full bluegrass band for about a year, consisting of Wiley Burchfield on the banjo, Page Heppler on the fiddle, and Sandy Sandusky on the bass. Unfortunately for the world of bluegrass music, they were, like many a new bluegrass group, not tremendously well received, and broke up the band without having ever done any recording in this style a great loss indeed.

On the advice of a fortune teller, they went back to Memphis and returned to the mandolin-fiddle-electric guitar sound, quite reminiscent of the Blue Sky Boys. In fact, in an interesting example of the teachers learning from the students, the Blue Sky Boys recorded the Louvin’s “Alabama” in the twilight of their career, as one of their last RCA releases.

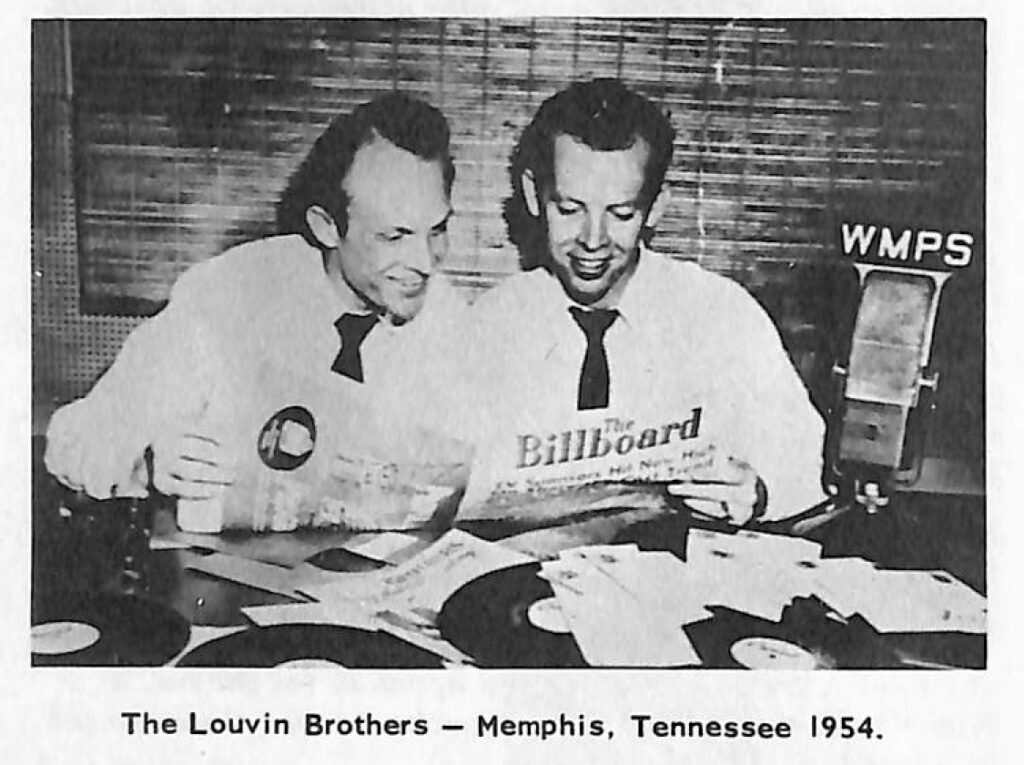

It was at this time that they began to achieve some success, and after “Weapon of Prayer” sold well on MGM, they moved to Capitol, and had quite a big hit with “The Family Who Prays” in 1952. This promising start, however, was halted abruptly when Charlie was drafted and sent to Korea, and their career remained at a standstill until his return in 1954. Joining Ira as a postal clerk in Memphis, they set about rebuilding an act and a career.

Determined to get back into the business, they began recording and releasing records for Capitol again, and Ira came up with the suggestion that they quit their jobs and move to Birmingham, Alabama, supposedly fertile territory. This they did with high hopes, but as Charlie tells it, “We got to Birmingham and found that Rebe (Gosdin) and Rabe (Perkins) had sung Louvin Brothers’ songs. If we had a release at 10:00 in the morning they’d have it on their 12:00 show. They had sung Louvin Brothers songs so much that by the time we got to Birmingham people thought we were impersonating Rebe and Rabe. That’s the truth honest to Pete! And it took exactly six months for me to go through it all. We demolished the bank account, sold the house trailer, and within six months we were down to just enough money to get out of town on.”

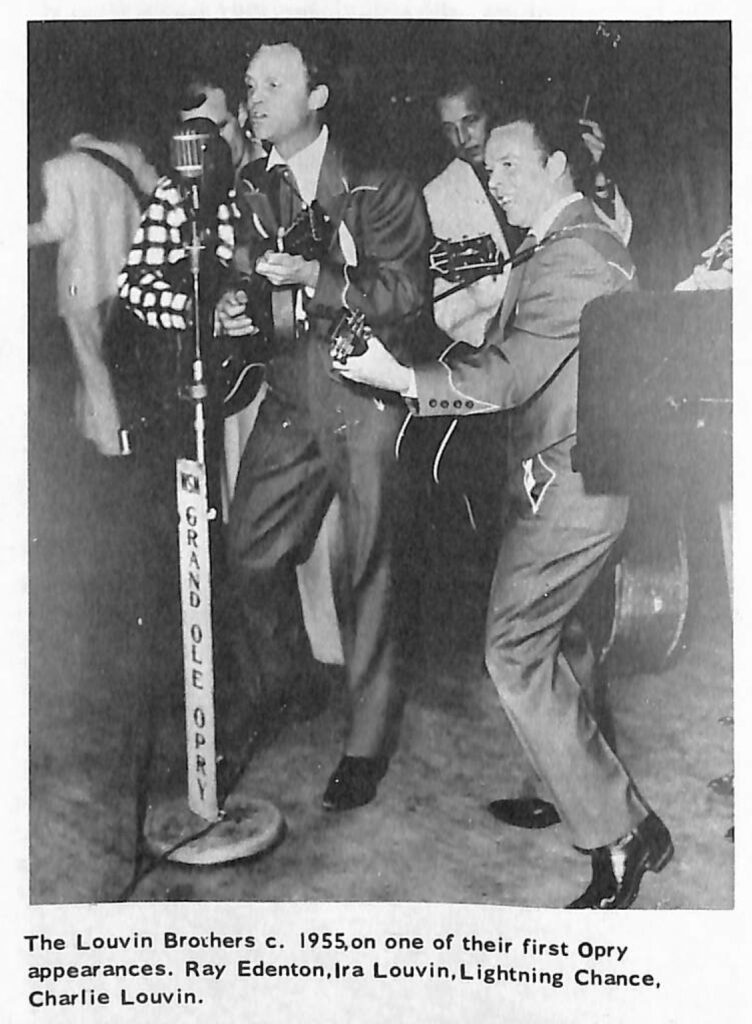

Broke and desperate, despite consistent record sales, they called their recording manager, Ken Nelson, who brazenly bluffed Grand Ole Opry manager Jack Stapp into signing them on the Opry, by convincing him that the rival Ozark Jubilee was about the take the Louvin Brothers on, and in January of 1955 they became Opry regulars.

The years 1955-1958 were the peak years for the Louvin Brothers, for, having convinced Capitol to let them record non-sacred material, they immediately had a number one hit with their first release “When I Stop Dreaming”. But the coming of Elvis, with whom they played his first 120 road dates, ultimately spelled hardship for their traditionally oriented sound, and when the slump that hit country music in the late 1950’s struck, it hurt “hard” country acts like the Louvin Brothers hardest of all.

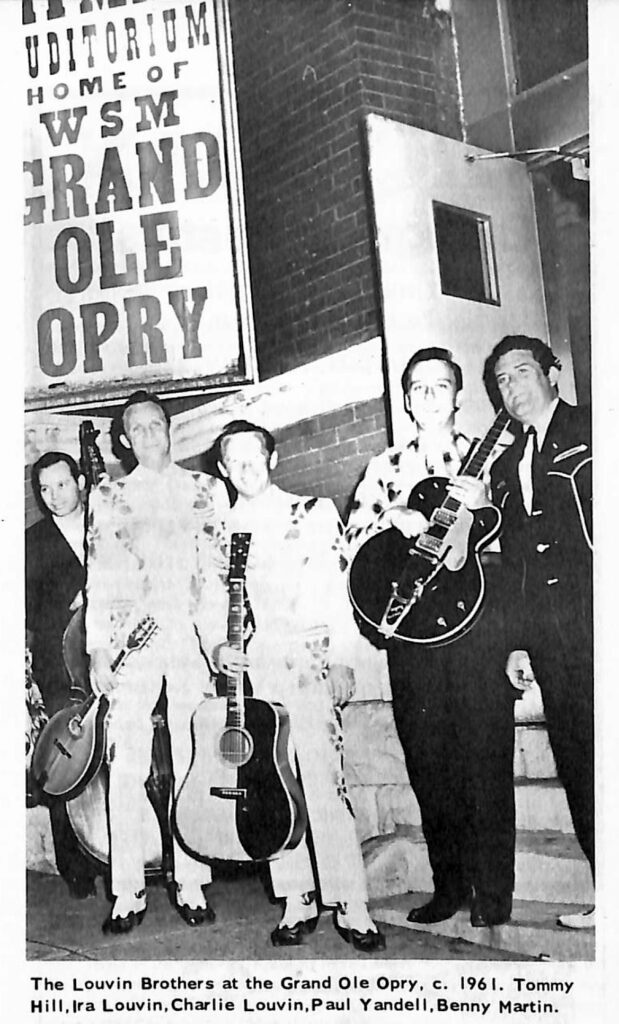

Discouraged and depressed, their music seeming to founder in a search for a more commercial sound, their personal relationship growing ever more strained, they formally dissolved the Louvin Brothers in August of 1963. After recording a quick album of his own, Ira moved back to a house on his parents farm, having largely given up the music business, except for an occasional club date. It was while returning from such an engagement at the Chestnut Inn in Kansas City that he was killed in an auto accident in 1965.

Charlie, meanwhile, recorded his first Capitol release, “Book of Memories”, a duet in the old Louvin Brothers style. Charlie sang with Tommy Hegan, a tenor-singing mandolin player steeped in the Louvin Brothers tradition. To his surprise, the flip side, a solo called “I Don’t Love You Any More” was an enormous success, an overnight number one hit, and it firmly established him in his, his company’s, and his public’s eyes as a solo singer. Since that time, he has continued to release consistent selling commerical country records, including such hits as “Will You Visit Me On Sunday” and “See The Big Man Cry”. He pays tribute to the old Louvin Brothers sound on each show, however, doing a medly of Louvin Brothers duets with his bass player, Rex Ellis.

- Their Records

The Louvin Brother’s recordings have all been deleted by Capitol and are now out of print, so get them while you can. The album of greatest interest to bluegrass and old time fans is their first on Capitol, “Tragic Songs of Life”, which contains many traditional ballads (“Katy Dear,” “Mary of the Wild Moor”, “I’ll Be All Smiles Tonight”) sung in a moving old time style, with, as always, fantastic harmony. An album of early MGM releases, on the budget Metro label, is also of interest (and also out of print). With fiddle and mandolin in the string band style, they sing such songs as “Weapon of Prayer”, “Changing The Words to my Love Song of You”, and “The Get Acquainted Waltz.”

The Louvin Brothers had planned four tribute albums, dedicated to artists who had shaped their career, and sadly, the two of most interest to bluegrass fans were never done. Besides the tributes to Roy Acuff and the Delmore Brothers which were recorded and released, there were plans made for a Blue Sky Boys album, and a Monroe Brothers/Bill Monroe album, which according to plan, would have had bluegrass accompaniment.

- Their Effect . . .

has been felt for the most part vocally. Charlie was, and is, a strong but unexceptional rhythm guitar player, while Ira’s mandolin work was thoughtful and often beautiful, but was derived from a simple old-time style and not up to the athletic standards that bluegrass imposes.

It was their singing, however, which has left a lasting impression on bluegrass music. Very distinctive in sound (although the further back you go, the more like the Blue Sky Boys it becomes), it smoothed out the rough spots of the older harmonies, yet maintained a power and a felling often lost by smooth-singing groups. Their versatility alone was remarkable they could move from the shouting camp-meeting style as on “There’s a Higher Power” to the understated emotion and brilliant harmony of “The Christian Life.” Harmonically, they ranged from the ultra-complex staggering of phrases on “Make Him A Soldier” to beautiful high lead duets like “I’ll Be All Smiles Tonight” and “Alabama.” Stylistically, they took a couple of flings into rock and roll in their later period (‘Red Hen Boogie’ and ‘Cash On The Barrel Head’), while—and this deserves special notice—recording a couple of the most bluegrassy sides ever heard from a non-bluegrass band: “The Get Acquainted Waltz” and “Seven Year Blues”. Subtract the already unobtrusive electric guitar, add a banjo, and these songs are quintessential bluegrass lonesome fiddle, high falsetto harmony, “blue” notes and all. And they compare remarkably in sound to some Bill Monroe recordings of the very same period: “When Golden Leaves Begin to Fall”, “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome”, and “The Old Kentucky Shore”.

Even more than their singing, however, their songs have left an indelible impression on bluegrass music. Jim and Jesse, most obviously and most naturally, have reaped the benefits of this store of material nearly every one of their albums has one or two Louvin songs included, and some of their most popular songs were originally learned from the Louvin Brothers “Changing the Words to My Love Song of You”, and “I Wish You Knew” to name just two. Likewise, the Osborne Brothers have recorded “Steal Away and Pray”, the McCormick Brothers “Ren Hen Boogie” and “Here Today and Gone Tomorrow”, and even Bill Monroe recorded a version of “Seven Year Blues” on his “Mr. Bluegrass” album some years ago.

- In Conclusion…

one of those apocryphal Bill Monroe stories that arc developing into legends. It is said that someone asked Bill who the greatest tenor singers in the history of Country Music were, and Bill replied “Ain’t but two, and Ira’s dead.”

Share this article

9 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Few country stars have had as much influence on bluegrass and other musicians. It’s hard to visualize Emmy Lou Harris’ career if she hadn’t known about Ira and Charlie.

The Bill Monroe quote sounds about right too, both for him recognizing Ira and for him recognizing himself.

Thank you for the article. Still very proud!

The Louvins left such a mark on real country music that has been copied by so many artists that went on to the top of the charts. Their music will live on and be studied for decades to come. Their story, I’ve often wondered , should be created into a movie to bring recognition to the hard work and persistence that they exuded to become a success. I listen daily to Pandora and I’m finding new recordings all the time.

Last year when I was at the Country Music Hall of Fame there was a video of the Louvin Brothers playing with Buddy Holly on lead electric guitar.

My Father had every record that these 2 guys have ever made and I grew up on there music and I loved each song they sung on the Gospel records.

The article left out the fact that the Byrds’ hit 1968 album, “Sweetheart of the Rodeo,” included “I Like the Christian Life.” Also, back in the early 1970s, the late Gram Parsons acquainted his then singing partner Emmylou Harris with the Louvin Bros. repertoire and she has since recorded many of them & her style is obviously influenced by theirs

I grew up on the Louvin brothers in the 60’s and 70’s in northern Maine! I know their sound after the first few notes! Great sound!!

The picture where it’s Tommy Hill, Ira & Charlie, Paul Yandell, & Benny Martin. That’s Jimmy Capps & not Paul Yandell. Yandell wore glasses. Just wanted to let you know. Love the write up. The Louvin Brothers are just a few of my many country heroes.

I love the music of the Louvin Brothers.