Home > Articles > The Archives > The Kentucky Colonels

The Kentucky Colonels

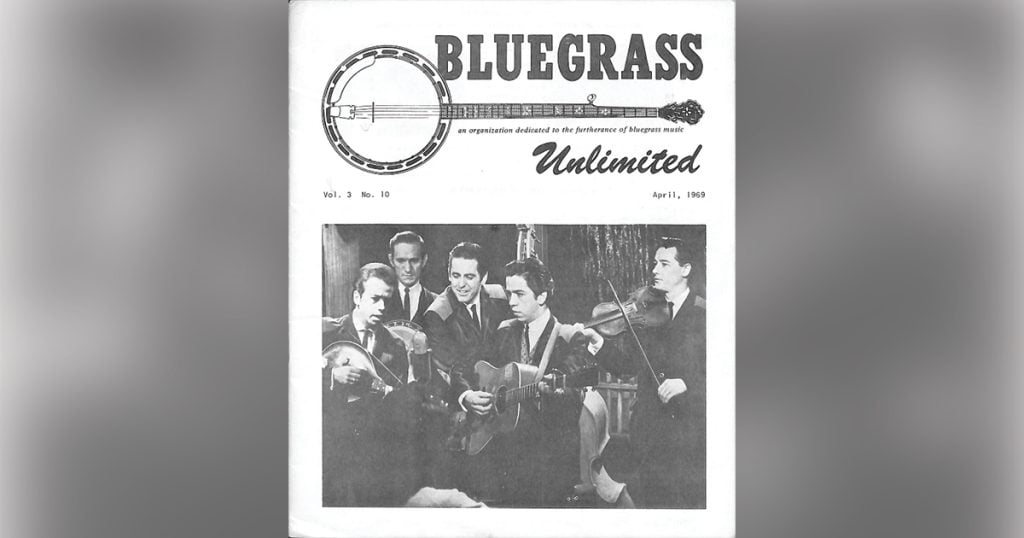

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April, 1969, Volume 3, Number 10

One of the most significant of the urban bluegrass groups of the 60s were the Kentucky Colonels or the Country Boys. They were known under both names. Though the groups disbanded in 1965, their music is still talked about today.

Their home base was the Los Angeles, California area and they, along with the Dillards, were amongst the most respected groups of the newer bluegrass generation.

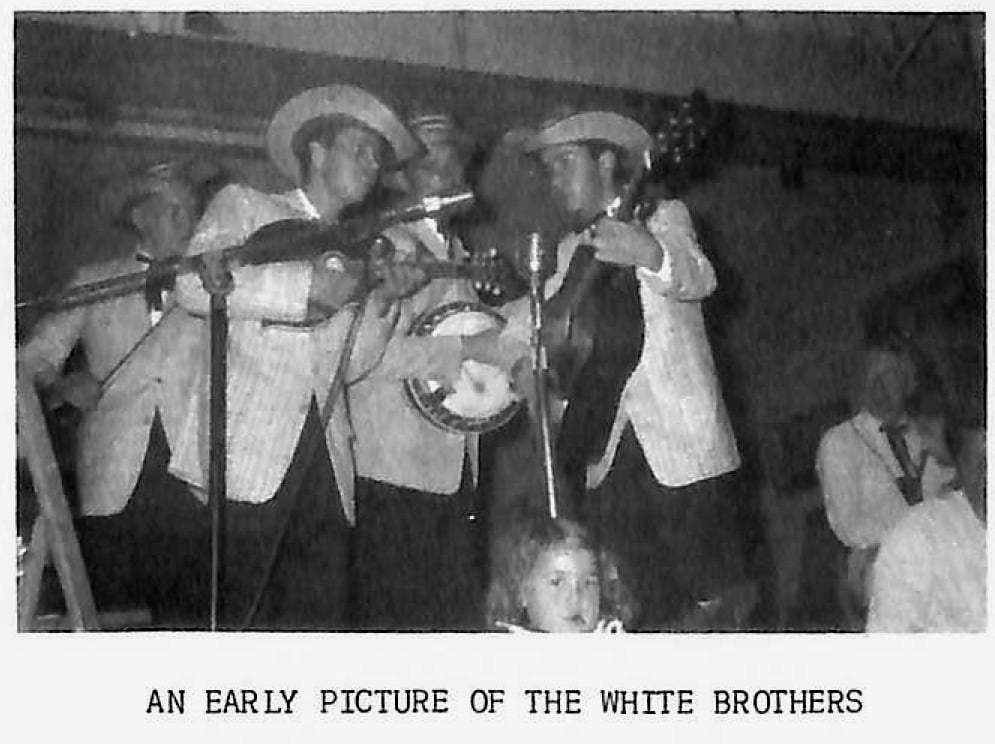

The groups started as a family unit in 1952, composed of the White children, Roland, Clarence, Eric and Joann. They started playing as a country band with a Louvin Brothers sound, and began doing bluegrass around 1954. They were all born in Maine, of parents who came to the U.S. from Canada. They moved to California in 1951. Their parents had country music backgrounds, and the family had uncles and grandfathers who played fiddle. The group was practicing one day and was heard by a neighbor who suggested they enter a talent contest held locally at a theater. They entered and won first prize, a TV appearance.

Roland White was the leader of the group. In 1958 they added Billy Ray (Latham) from Cave City, Arkansas on banjo. Roland had been playing banjo approximately one year prior to that but when Billy Ray came he returned to mandolin. In 1959 they added LeRoy Mack on Dobro, and shortly thereafter made their first record on Sundown. They were mainstays on the West Coat TV shows “Town Hall Party” and “Hometown Jamboree”, even through their average age was only eighteen.

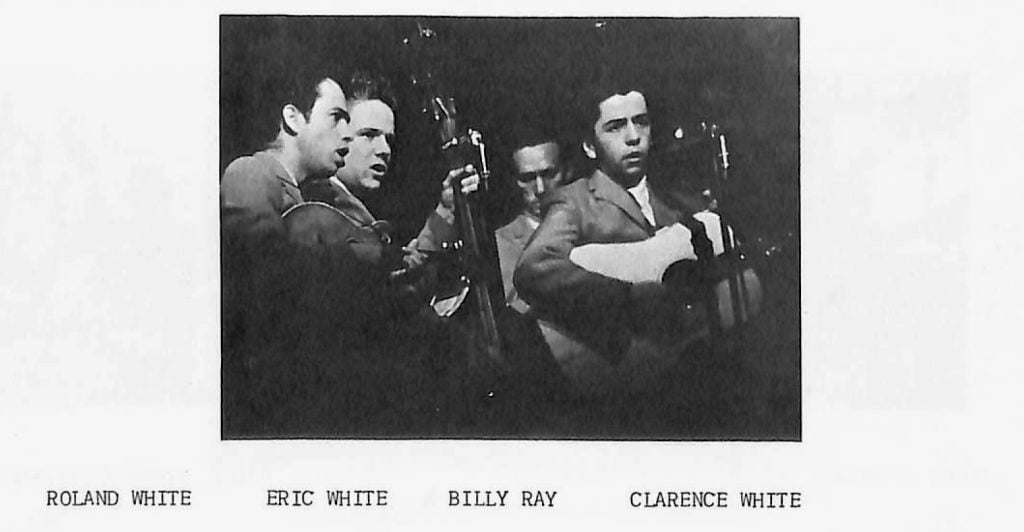

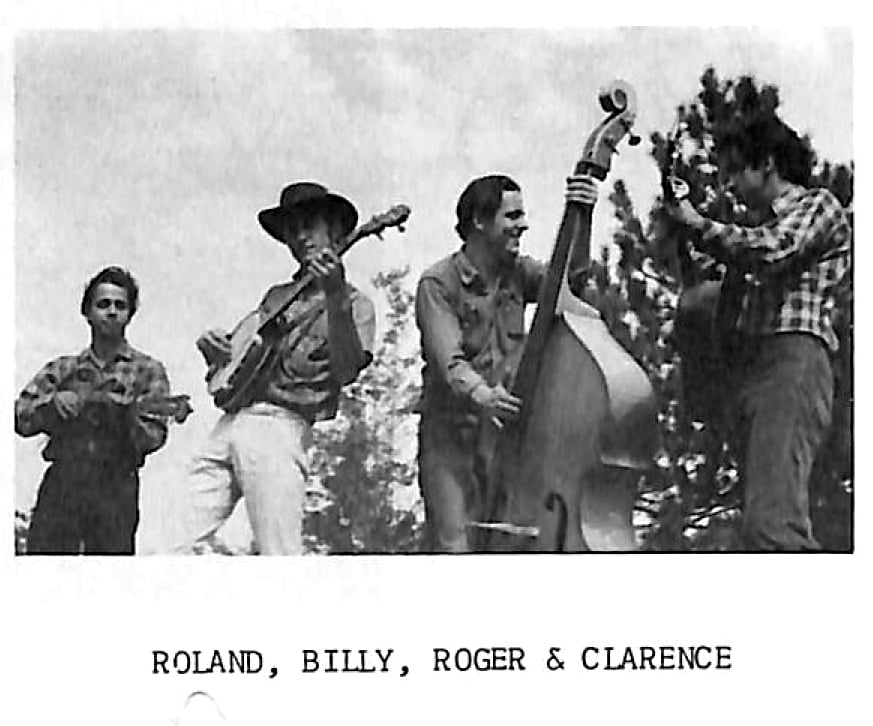

By this time the group consisted of Roland White-mandolin, Clarence White-guitar, Eric White- bass, Billy Ray-banjo and LeRoy Mack-dobro. They also recorded some sides for Gene Autry’s label for which there is no further information on at this time. In early 1961 they added Roger Bush on bass fiddle and second banjo to replace Eric who had recently married and did not wish to travel. They recorded four appearances on the Andy Griffith TV Show at this time.

They also recorded four songs on an LP with Andy Griffith “Songs, Themes & Laughs from The Andy Griffith Show” – Capitol (S)T1611 which was released around November of 1961. Things were starting to pick up for them when Uncle Sam beckoned to Roland and called him to the Army from 1961 to 1963. The group functioned without a regular mandolin player and added a rhythm guitar player. Clarence White, after hearing Doc Watson at the Ash Grove in Los Angeles, started playing lead guitar and using mandolin-style breaks. Since Clarence’s background was in bluegrass rhythm, he was able to take a lot of Doc Watson’s lead picking technique and integrate it tastefully into a bluegrass band.

During Roland’s army service, thanks to the help of Joe Maphis, the Colonels made their first lp on the Briar label, owned by Paul Cohen of Nashville. This lp marked the beginning of the “Kentucky Colonels.” Briar did not want to release the record under the name of the “Country Boys” and phoned the group giving them a list of names to pick from. “Kentucky Colonels” was the lesser of several evils and from then on that was their name.

Before Roland returned in 1963, they added Bobby Sloane on fiddle. Bobby was unique in his approach. He was left handed, but played a standard strung right hand fiddle. When Roland returned, the group became more active, touring in New York, Washington, Detroit, the Dakotas and Canada. They also appeared at the UCLA and Newport Folk Festivals in 1964.

Everywhere they played they drew acclaim as one of the most impressive current groups in the business. During 1964 their home base was the Ash Grove in Hollywood, California. Through its mentor, Ed Pearl, their recording activities increased, with their use as session musicians on Dick Bock’s World Pacific label. World Pacific, thanks to the success of Glen Campbell’s twelve-string guitar lps became active in recording West Coast bluegrass material. The Colonels made one lp and backed Tut Taylor on both of his. They appeared in a movie entitled “Farmer’s Other Daughter” and as Roland put it: “it’s a real winner, you might see it on TV sometime on the late, late, late, late show!”

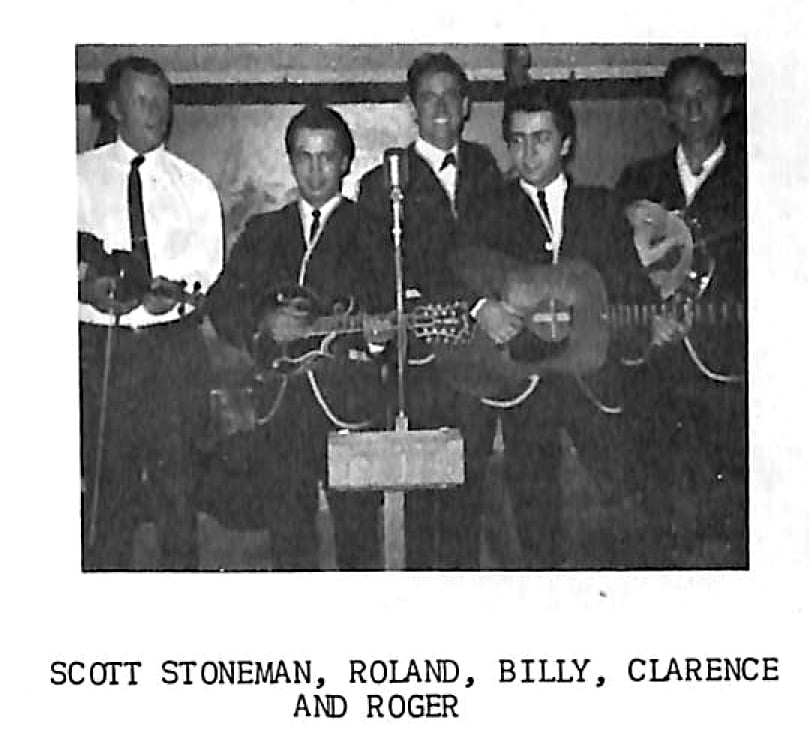

One of the groups active on the West Coast at the time were the Stonemans. After Bobby Sloane left the group, Scott Stoneman joined the Colonels playing fiddle. This combination of Roland White on mandolin, Clarence White on guitar, Billy Ray on banjo, Roger Bush on bass and Scott

Stoneman on fiddle was one of the most exciting sounds to come along in quite a while. Scott’s added impetus was the spark that really turned on each one of the individual members to their utmost. It is a shame that only tape recordings are available of this band. Their music was just unbelievable. Clarence inspired Scott, who inspired Billy Ray, who inspired Roland, who inspired Roger, who inspired Scott. The process was cyclical and magnificent.

When the group disbanded in early summer of 1965, Clarence became a studio session guitarist on rhythm and lead (electric and acoustic) around Hollywood recording with Wynn Stewart and Ricky Nelson. He is now playing guitar with the Byrds, of rock fame. Roland White, as most of the devotees of bluegrass know, is now playing guitar and singing lead with the Blue Grass Boys, adding a lot to the current sound of Bill Monroe.

Billy Ray (Latham) has returned to Arkansas and is working as comedian and banjo player on the Ozark Opry. Roger Bush has faded into obscurity and his activities are not known at the present.

Bobby Sloane is now playing bass with J. D. Crowe and the Kentucky Mt. Boys around the Lexington, Kentucky area.

If you are able to find any records by this fine group, do get them. You will be quite impressed with their contribution to bluegrass music.

Records By The Kentucky Colonels (Country Boys)

Sundown 45-131—I’m Head Over Heels in Love with You/Kentucky Hills

CAPITOL (S)T1611—The Andy Griffith Show: Flop Eared Mule/Sourwood Mountain/New River Train/Cindy

WORLD PACIFIC ST/WP 1821—Appalachian Swing

WORLD PACIFIC ST/WP 1816-12 String Dobro-Tut Taylor with Roland White, Clarence White WORLD PACIFIC ST/WP 1829-Dobro Country—Tut Taylor with Roland White, Clarence White & Billy Ray Latham

BRIAR-109—The Kentucky Colonels

1964 And The Kentucky Colonels

By John Kaparakis

Almost every one of us measure our lives in terms of years. Our birthdays and other anniversaries which we celebrate, as well as many of the events we either look back upon or look forward to are thought of in terms of years—”ago” or “from now”. Certainly, some years will be better than others for any given individual, and the determination of our years as being ones good or bad for us is quite often judged by one single event occuring therein. This is the case with me as I look back over 1964, one of the best years of my life, which was made so because of one event–becoming acquainted with the greatest bluegrass band ever. The Kentucky Colonels.

Actually, I met the Colonels just before Christmas in 1963. Word of this amazing group from California had not then filtered across the country to the East Coast and the Washington, D.C. area where I live, but the name Clarence White rang a bell as being the musician credited with doing the brilliant guitar breaks in the Weisberg-Brickman album “New Dimensions in Banjo & Bluegrass” which had been released that year. Upon hearing that The Kentucky Colonels were coming to town, I, and many others reacted more with curiosity than anything else, but this turned into wholehearted praise after listening to their first song. Here was a group of musicians who came to town as strangers, and who left as heroes.

The Colonels had been on tour then since around September, 1963, and they returned to California for Christmas—but not before giving the East a preview of what to expect in the way of music the following year—1964—when they were to come back for an extended tour. Come back East they did—did they ever!

During the Spring and Summer of 1964 I was very fortunate in being able to personally witness in many sections of the East, the tremendous response given The Kentucky Colonels. I saw the Boston audience thrill to their performances at The Unicorn in May, just about the time their World-Pacific album “Appalachian Swing” was released there. What better way to celebrate Independence Day than to be in Cambridge, Massachusetts seeing the Colonels pack the Club 47 for three straight appearances. Then came Newport, with its distinctive array of talent and top names in folk music. I must say a few words about Newport here, because that was one of the Kentucky Colonels’ finest hours, and they performed for that enormous crowd like the champions they are, winning many friends for bluegrass music in the process:

No amount of words or descriptions on my part could come close to adequately portraying the tremendous spectacle that was Newport, 1964. One had to see it to believe it. 1964 was one of the last years that the “big guns” were all there at once—Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Mississippi John Hurt, Peter, Paul and Mary, Chad Mitchell, Judy Collins, Odetta, The Clancy Brothers and many, many more. The abundance of music and spirit for folk music displayed by literally thousands upon thousands of people for four days and nights was absolutely staggering to the imagination. Everywhere one went and looked, there were people camping out in tents, or in sleeping bags occupying every available inch of ground space, and these people were gathered together at any hour of the day and night with guitars, banjos and autoharps, and singing and playing with an enthusiasm the likes of which cannot be described.

But in all this hubbub and confusion of musicians and spectators, there were four young men that stood out like bright stars shining through a murky night sky. Four young men came to Newport virtually unknown to almost everybody there, but they left an indelible impression in the minds of all who saw them perform on the three workshops and two concerts of which they were a part. Only four young men whose musical talents are limitless could have handled the difficult assignment of following on Sunday night’s concert a performer who received a standing ovation at the mere mention of his name—Pete Seeger. And these four did follow Pete Seeger on the show, and did so in a manner completely befitting the dignity of their band’s title, and by displaying their usual good measure of talent in perfect musical execution which stimulated the audience to receive this bunch of newcomers with a warm and rousing tribute of applause. Splendid indeed were the performances by and reception afforded these four young musicians, who did more in four days to boost the concepts of bluegrass music to the audience at Newport than any other representative group could have done in twice the time—of course I’m talking about The Kentucky Colonels.

Yes, the Colonels made their mark at Newport. And I was very glad to have had the opportunity to see them perform. I was there in the audiences that welcomed them to the various workshops with for the most part the quiet and polite applause a little-known group is given; but which quickly changed to delighted cheering and rousing hand-clapping upon hearing those guys play.

I observed several of the young hopeful banjo picker types watch Billy’s every motion with admiration as he demonstrated his style in the Banjo Workshop. I sat next to people in the Religious Workshop who, upon hearing The Kentucky Colonels quartet singing, said: “I don’t know who they are or where they come from, but they’re great.” I was there when one of the greatest and best-loved guitarists of all time—Doc Watson—picked some twin guitar with Clarence on the Guitar Workshop, and paid Clarence an important tribute to his musicianship by injecting comments such as “play it pretty now” and “pick me some hot licks” when it came Clarence’s turn for a break. Talk about something blowing your mind—Clarence and Doc’s combined talents were almost too much for the audience and this writer to be exposed to at one time. That was the best music I have ever heard.

All of the times I saw the Colonels play that year, their consideration of people for whom they worked and to whom they performed was very much in evidence. As an example:

At Newport, the Colonels were enjoying Sunday afternoon off from appearances, and were relaxing over at Free-body Park listening to the New Folks Concert. The Colonels received word while there that, due to an administrative mix-up which was entirely no fault of their own, they had been scheduled to appear at Diamond Hill State Park that afternoon, a distance of 45 miles from Newport. A crowd of over two thousand people had been waiting for them at Diamond Hill Park since two o’clock—it was then 3:30 p.m. After a frantic search through the crowd to round up Kentucky Colonels, they dashed back to their lodging, grabbed their instruments, and jumped in their car—changing into their band attire en route. The boys arrived at the park around five o’clock, and played one of the best shows I’ve ever heard them do. The Colonels were featured on the main Folk Festival Concert that night at 8:00 p.m., so their appearance at the park had to be cut short at six o’clock to allow the boys time to get back to Newport. The audience displayed their gratitude and appreciation to the Colonels by a resounding ovation—even after waiting three hours to hear them. I know the Kentucky Colonels will long remember that afternoon, and so will all the grateful fans at Diamond Hill State Park.

The beginning of August took me with the Colonels to Baltimore, when The Foghorn folk club was jammed with people and enjoyed the best attendance in its history. Then on to New York, where the Colonels notably impressed the usually stolid New York pickers, and had many of them conceding the “best bluegrass band” honors to The Kentucky Colonels. One last fling for me—Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., a swinging summer resort island where the Colonels packed the house each evening, and had a little time in between for swimming, relaxing and rushing to meet their wives on the ferry boat from Woods Hole! Jim Kweskin was booked in Martha’s Vineyard at the same time, and this produced some out of sight jam sessions involving the two groups— especially Clarence, Roland and Bill Keith, all of whom are without equal on their instruments.

A few more appearances at New York and Boston, and then the Colonels were off cross-country again, performing as they went in Chicago and other cities on their way back to California.

When the Kentucky Colonels left the East in the Fall of 1964, their many fans and friends here were all hopeful for their return in 1965, but this was not to be. The Colonels tried desperately to make it playing music for a little over a year after their return to California, but they could not. When picking bluegrass music was obviously no longer providing them even a meager living, they even tried switching their style—anything, to keep the group together, but to no avail.

Everyone can point to great catastrophes and misfortunes in history, according to his own bag. Political scientists can cite assassinations of Presidents, sociologists will evidence discrimination toward minority groups, historians have their wars and economists their depressions. But to me, the greatest single tragedy to befall mankind was the breakup of the Kentucky Colonels.

Music-lovers, do not despair. Miracles have happened before, and maybe someday we will see the Kentucky Colonels re-unite and again lay upon us the best vibrations ever to be heard from the finest grass band ever to take a pick to a set of strings. And if this happens, I sincerely hope that each person who ever meets and hears the Kentucky Colonels will come to find that as a result of doing so, he or she will enjoy a year as much as I did—1964, the Year Of Our Lord, and the Year of the greatest bluegrass band ever—The Kentucky Colonels.

A special word of thanks is given to Clarence and Roland’s mother, Mrs. Eric White, and to Clarence’s charming wife Susie (who makes the best blueberry pancakes in Martha’s Vineyard!) for the pictures of The Kentucky Colonels which accompany this article.

Share this article

4 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Regarding Doc Watson’s influence on Clarence White’s guitar journey, in addition to seeing Watson at the Ash Grove around 1962, Clarence played rhythm guitar behind Watson at someone’s house in L.A. There’s a tape of that performance and I have a copy. Watson did most of the fancy fiddle tunes he would later put out on record, like ‘Beaumont Rag’ and ‘Fisher’s Hornpipe’. I had always wondered why Clarence never took a break on any of the 21 tunes on that tape. Now I know why, he just hadn’t learned lead guitar by then, at the age of 18. I wonder if Doc Watson realized later how important his influence was on Clarence’s development.

According to Ibiblio and Fred Bartenstein, on the Tut Taylor ’12 String Dobro!’ World Pacific album it’s John Piazza (or maybe Glen Campbell) on 12 string guitar and Chris Hillman on mandolin. Since this album was released in February 1962, I speculate Clarence was still working on his guitar stylings then.

I bought the World Pacific LP “Appalachain Swing” many years ago not knowing what I was getting exactly. I have since worn the grooves out. Clarence White blew my mind away until years later when TR came along. So sad to see the passing of great bluegrass musicians.

Regards Williams Forrest’s comment from April 2022, it’s more likely that Tut Taylor ’12 String Dobro! was issued in February or March of 1964, rather than 1962. The March 14, 1964 issue of Billboard lists Tut’s album with the Folkswingers, 12 String Dobro! [World Pacific S 1816] as a three-star pick new release. Also, and this is not small point, Hillman did not come into the sphere of World Pacific until January or February of 1964 when producer Jim Dickson took the Blue Diamond Boys, Hillman, Vern and Rex Gosdin, and Don Parmley, under his wing, ultimately recording the Hillmen LP later that year.