Home > Articles > The Archives > The Jerry Douglas Story

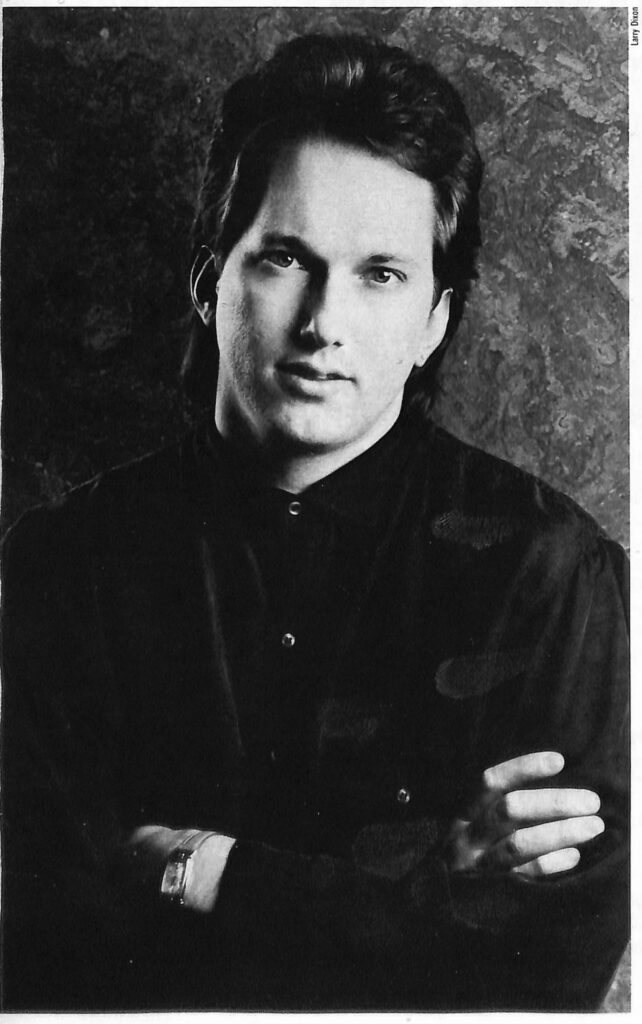

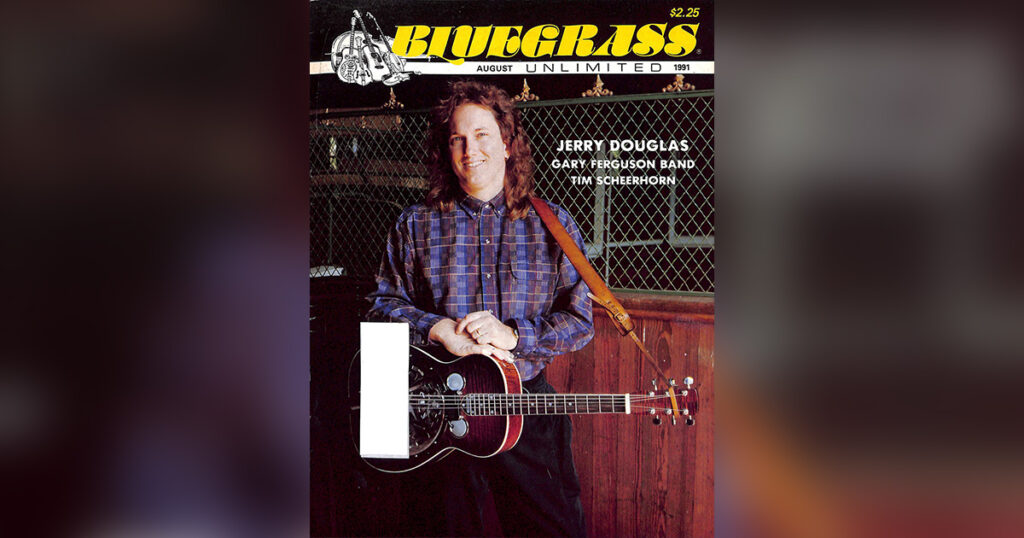

The Jerry Douglas Story

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1991, Volume 26, Number 2

New grass, bluegrass-fusion, country-rock, new-country, super- picker. All these terms and more have been used to describe or explain the new breed of hot pickers such as Jerry Douglas. They are usually in their late ’20s or early ’30s. Their parents were born in the ’30s or early ’40s and were working people of the Southeastern United States—that large group of parents responsible for the “Baby Boom” of the ’50s. These parents were determined that their children were going to have a better childhood than they. The times were prosperous and allowed this to happen or maybe their determination was partly responsible for the prosperous times.

As a result, a new generation of pickers was born into a situation that allowed the time to learn to play, that gave them a better selection of instruments and a parental encouragement to “do their thing.” Further, the early teen years of these kids was during the same period that bluegrass festivals were coming into their own. These parents, with their love of country, hillbilly, bluegrass or whatever, attended the festivals with the children and were more than happy to see their offspring’s interest in string music. I attended many of these early festivals with two of my three sons and both became pickers.

The background of Jerry Douglas is much like described, and so I believe the theory has some merit.

Jerry and many of the other future superpickers proceeded to master the older, standard techniques and styles and then began to experiment and develop a new level of instrumental expertise. They had all the earlier works to copy and work from.

To their credit and without any negative reflection on their musical ancestors, the young pickers have, to a great degree, done as much in their approximate twenty years picking history as the older super-pickers did in a lifetime.

Jerry, when and where were you born?

May 28, 1956—8:00 p.m.—Warren, Ohio.

Your Mom and Dad?

Autha Nae and John Douglas. Her maiden name was Dennison and they were from Braxton County, West Virginia.

Brothers and sisters?

Only one brother, Blaine, three years younger. We looked about the same but were completely different people. He played the bass, still does and is good.

So your parents were West Virginia people that moved to Ohio?

Yes. Dad got out of the Navy in 1955. He had a cousin, Donald Douglas. Dad and Donald had a double wedding and both couples moved to Warren at the same time. There was no work [in West Virginia] and like a lot of other couples at the time, they went to where the work was.

I know what you mean. We moved to Ohio from North Carolina in 1954. I have a lot in common with your dad. We all had a poor background, textile mill, farming, mining or whatever and weren’t content to do like our parents. We wanted something better.

Well, we didn’t have money to throw away when I was growing up but we never wanted for anything. There were lots of kids to play with, never any real worries. Most people we knew were from the same background in Pennsylvania or West Virginia.

I was pretty good in school. I played football all through high school. I broke my thumb several times. Caused a bad angle on it which is probably why I wear out picks so bad.

I was going to go to college—University of Maryland. I had a chance for an English Scholarship-ended up with the choice of college or music. I had played on the road with the Country Gentlemen all summer prior to my senior year so I chose music.

Anything else about childhood or family?

Dad and his cousin Donald both worked for Copperweld in Warren. Dad retired about two years ago and moved back to West Virginia. He and Mom built a log cabin on top of a ridge on my Mom’s homeplace farm near Sutton.

What, other than music has been your line of work?

I’ve always played music. Travelling has actually been the job part.

John Douglas and the West Virginia Travelers must have influenced your early musical career?

My father was my main influence—my drive. I started playing mandolin when I was five. Dad called a neighbor over one day just to witness that I could play a solo.

Did your dad play before moving to Ohio?

Yes. The usual country standards. A good friend, Johnny Simon, on guitar and a cousin, Arden, on mandolin.

One of the first people he met in Ohio was Virgil Hardbarger who became the fiddle player in the West Virginia Travelers. Harry Shafer, a great banjo player was there. Harry could have played with any bluegrass band in the country but he worked in a factory supporting his family. There was also Paul Lemmons, bass player and tenor singer. I remember standing around just watching those guys play when I was five or six years old. Those guys were such good musicians. They could really play!

I remember your dad doing a lot of Osborne Brothers’ stuff.

Yes, that and a lot of duet things. I have a vivid memory of Dad and Paul doing, “I Don’t Believe You’ve Met My Baby.” There was always Flatt and Scruggs, Reno and Smiley, Jim and Jesse but not much Bill Monroe stuff around. Anytime those guys came to town we went to see them.

A lot of the bands came to Canton as I recall.

Yes and to the Dennison Theater in Cleveland, and to the Stambough Auditorium in Youngstown.

So your father was your only major musical influence at first.

A grandfather, I never knew, was a part-time fiddle player but my father was the only one in the immediate family. Probably an evolutionary thing. Seeing all those bands, hearing all that music and looking for something to do, I just wanted to be a part of that band and to try to please my father as every young boy does. I was musical right away. It was more than practice. It was also really thinking about it and wanting to please my dad.

So you were about five years old and picking the mandolin, what came next?

I got a Silvertone guitar for Christmas about 1962 or 1963.

I remember your dad playing an Amish community, Middlefield, Ohio on Sunday afternoons. I don’t remember you there.

No, I don’t remember much about that. It was probably around 1964 or 1965. I hadn’t started Dobro yet. That came when I was about ten, in 1966.

We saw an Opry review in Youngstown with Flatt and Scruggs, Roy Acuff and Jim and Jesse. Two Dobros on the same show. I wanted to play a banjo, Harry was so great, but after that it was strictly Josh Graves’ Dobro.

After the Flatt and Scruggs show I asked Dad to raise the nut on the Silvertone and I’d play it. He did that, the next day and then cut a piece out of a tubular hacksaw for my first bar. We just tuned it to open “G” and I started playing it. We kept our guitars on a cedar chest in the bedroom. We came home one day and found the Silvertone folded up. [It] couldn’t stand the sun coming through the window. I was devastated. This was about a year after I’d started playing the Silvertone—Dobro style. We had been looking for a real Dobro. Just never saw one in that part of the country. We heard of one up in Niles, Ohio, so we got it—“F” holes and coverplate. We stopped by some friends in Newton Falls on the way home but I didn’t even get out of the car. I just sat there and played. It was the greatest! Next day we checked it out and it was just a coverplate with nothing under it!

Boy, do I remember. My first real live Dobro was a Beltone. A coverplate with a black paper speaker cone under it! I ordered my first proper Dobro from a brochure.

We did too. Probably the same brochure. A fourteen-fret model. That was about the same time I got my first real steel bar. Romey Richards, mandolin player in Dad’s band gave it to me.

The rest of your Dobro history?

Number two was a 1932 “Lady Dobro,” fourteen-fret with a round neck. Dad bought it from Lonnie Wilman in Ravenna, Ohio. Sold it to Ron Messing who was taking lessons from me! Dan Huckabee once flew in from Texas to take lessons when I was a junior in high school. They lost his Dobro for a few days. Number three was an old Dobro with the solid peghead—the one on the front of “Fluxology.” I got it from Norman Gordon. He sent me pictures and I picked it out. I played that Dobro from about 1974 to about 1980.

The R. [Rudy] Q. Jones mahogany was next and I remember seeing you with it in Greenville, South Carolina, right after you got it. That was the first Jones mahogany I’d seen. Tell us the story.

Rudy was around at different places and times with his walnut instruments. His pitch was that they were loud and could compete with the banjo but I was looking for a different tone. I told him to build one of mahogany and if I liked it I would play it.

You haven’t played anything since?

I just recently got an instrument from Peter Slama. He’s been in this country for about five years. It’s his number four and is all Brazilian rosewood. He says the others are not good. He’s got number two and number one he sold to a guy in Austria to get money to come to this country.

What Dobros were used with which bands?

I used the Mosrite on the Country Gentlemen “Remembrance and Forecasts” album. The Norman Gordon Dobro was used with the Gents and with J.D. Crowe, all through Boone Creek and about the first year with the Whites.

Any other instruments? First the mandolin, then guitar, then Dobro. Recently I saw you playing a red guitar on your lap Dobro style.

That’s really a lap steel built for me by Joe Glaser. It’s like a little Stratocaster. I have a collection of lap steels. I love the sound of them. My lap steel hero is multi-instrumentalist David Lindley.

Let’s talk about some things the Dobro pickers will want to know about. First, your strings.

GHS. I used the gauges for a long time by buying them separately. J.L. Poff, a friend with a music store in Christiansburg, Virginia, called GHS and told them they should put them out as a set and they went for it. They are semi-flat wounds, actually a round-wound, ground down somewhat flat.

They give a lot less problems wearing out picks and all that. I think most Dobro players use about the same gauge.

How often do you change strings?

I get about three sometimes four forty-five minute sets before changing. If I’m in the studio I’ll make notes about the age of the strings so if I have to go back I’ll go with strings about the same age as before so it will sound the same. I change strings one at a time to maintain pressure on the cone.

So, it’s forget about this business of renewing strings or using them a long time.

Unless you live in Eastern Europe. Those guys can’t get strings. I save my old ones to send to them.

Your bridge insert—anything better than maple?

No. I’ve tried all sort of things. Ivory, ebony, walnut and the best and most consistent is still maple.

The nut?

I like ivory and bone. I don’t like metal and the synthetics. I can hear a difference.

Your problems with sinking cones before and after the Quarterman cone?

Ah! With the old ones it was a regular occurrence. After you had it set up about four times you had to change the cone. The amount I played might have had something to do with it but with the Quarterman, I have it set up once a year.

That answers another question about strong cones and weak cones.

They were different but these Quartermans just go on and on, [they’re] much stronger.

Do you believe in gluing or nailing the cone in place?

No. I like mine sitting free.

Who does your set up?

Gene Wooten.

Have you changed the cone in your instrument?

No. It’s the same one that came with it in 1979.

Ever had trouble getting it to sound just right after set up, changing strings, or any other work?

No, these parts all seem just suited for each other. No trouble even after being broken last year.

Your cone adjustment?

Once you feel tension on the screw, just a quarter turn more. If you’re getting buzzing, don’t try to tighten it out. You’d better check it, for something is not right.

Your picks?

The ground-down semi-flat strings help here and cut down on bar noise. Even at that, I use a lot of thumb picks. I cross my thumb some and rough strings cut a notch in it. I use plastic thumb picks and .025 Dunlop metal fingerpicks.

Any tricks to keeping your picks on?

No. I used to use fiddle rosin but my fingers got gummy and I couldn’t get it off. Now I don’t use anything and just take my chances. They’re going to move. That’s why I use heavy metal picks so they won’t bend. I keep hitting them in the palm of my hand to keep them in place.

If you don’t pick for a while, does your instrument go dead?

Maybe a little. But no Dobro I’ve ever owned has gone longer than a week without picking.

On warming up and practice?

I’m never on any kind of a practice schedule. For warming up I’ll just pick notes on the scale to get coordination.

Do you use different tunings?

I never veer much away from regular “G” tuning. I’ll sometimes drop the “B” to an “A.” For minors I don’t retune. I did one time on a Country Gentlemen record.

For the people who are looking for an instrument that sounds like Jerry’s or Josh’s or Mike’s, how much is instrument and how much picker?

I’d say (big pause) it’s 65%—70% the individual rather than the instrument. The picker adjusts to the instrument and tries to get what he’s used to hearing out of the instrument he’s playing.

Playing in the dark?

Tough isn’t it? (Laughs) I’m used to my guitar and I don’t look at it much.

On being protective about picking secrets?

I had that feeling for a long time and really battled with it. I finally figured that if there’s somebody out there that’s gonna play my stuff better than me, they’re gonna do if anyway. There’s no sense in anyone being afraid to teach what they know. I now have an instructional video with the Homespun label.

You know what is said about the sincerest form of flattery!

True. When I first started playing I copied Josh and I got about as close as anyone could want, but I wasn’t him. Then I played like Mike Auldridge. I think everybody has to go through the process of finding their own style.

Do you see a need for more than one Dobro for the different needs such as stage work, studio work or just sitting around picking?

One Dobro can cover all.

Your thoughts on electrifying?

We’re playing to bigger crowds and we’re competing with louder things on stage. I did quite a few things with different cable and box arrangements and then added a switch so I didn’t have to stay in front of the mike. Richard Bataglia worked up an arrangement that works well. The New Grass Revival used it. You use a stereo cord that splits the signal. It uses mostly the mike but also the pick-up for gain gives good control. On tour with Gary Morris, I put a Countryman mike in my Dobro and a magnetic pick-up at the end of the fingerboard.

Tell us about your capo history. (Jerry gets and displays an assortment of bars and capos.)

. . . My first capo my Dad made. . .then the first one by Ray Spinaugle. . .a fellow that makes my bars, Ron Tipton, made this capo. . .here’s a Gene Wooten capo. . .Chuck Mills made this brass bar for me. . .

Been using a Ron Tipton bar for over five years, no sign of wear.

The refined Ray Spinaugle Capo was the model for the Jerry Douglas Capo. I hardly ever play with a capo now.

Here’s your chance to answer all those calling you a capo freak.

I was one of the first professional Dobro players that was heard a lot using a capo. Because it hadn’t been done much I suppose that’s why. But it allowed me to play fiddle tunes in “A” or “Train 45” in “B” using the open strings.

I used a capo for years for the same reasons as you. I see it as no different than a guitar or banjo picker using a capo.

Right, it’s just to get the open strings. Maybe a lot of people didn’t like it because they didn’t have a capo!

There were no good Dobro capos in the ’60s. I’ve made three batches since I filed out my first. Tell us about the Jerry Douglas capo.

The whole story is that I had 200 made and sold them all.

Will you make more? They were good and I think you should.

Well, what’s the market? There are many capos around now. They were very expensive to make as it was mostly machining of all the parts. I just don’t know. The Leno Capo Company makes the best one right now.

The Jerry Douglas sound, your desire, the instrument; was there a distinct point at which you knew you had found it.

Sometimes you surprise yourself and play something you didn’t think you could play. You hear a sound that’s pleasing and you realize that’s what you’ve been trying to do. The Dobro is a limited instrument but I knew I could make sounds that hadn’t been heard on it before.

But did you ever reach a point where you could say “Hey, I’ve got my own sound.”

No, I think other people have told me and that’s when my sound or style was recognized.

Did you hear the “sound” all along? Did it change over the years?

No, it didn’t change. I liked the sound Josh got when he played hard and the sound Auldridge got when he played with his right hand up the neck a bit. Also, I liked Lloyd Green’s tone. He played on Don Williams’s records. One of the most tasteful players ever!

So it was mostly hearing some sounds you liked and locking in on them?

It was also knowing what kinds of sounds it could make and going from there. It was a sound that was in the air that I wanted to make on this instrument. So when I made the sound it was “let’s see what I did.”

And the instrument part of the “sound?”

The Jones was the first. It had the sound I was looking for.

Let’s talk band experience. It started with John Douglas and the West Virginia Travelers. Take it from there.

Dad had a real good band when I last played with them. Harry Shafer, Ray Spinaugle, Dave Clark and Bernie Crawford. We had a good following at the Grizzly Bear Saloon in Warren. I made $15.00 every Saturday night. It was great. I played my first summer with the Country Gentlemen in 1973. Graduated May 26, 1974, played Ponderosa Park in Salem, Ohio, on the 27th, turned eighteen on the 28th and moved that day to D.C. I worked a year with the Country Gentlemen. Then in June, 1975, I moved to Lexington, to work with J.D. Crowe. I worked with him about three months. We went to Japan during that time. After that Tony Rice went to California to work with David Grisman. Ricky Skaggs and I left and started Boone Creek.

So you and Ricky were the founders?

Yes. We were to get Keith Whitley, Marc Pruett and Lou Reid. Whitley just wouldn’t quit Stanley,

Marc had too much going with his music store and other things and Lou couldn’t leave until his tobacco crop was in. Eventually, the band started with Wes Golding and Terry Baucom. Boone Creek lasted three years. We cut two albums and there’s a bunch of tapes scattered around the country. We broke up in 1978.

Then what?

I went back to the Country Gentlemen. I was at a personal low point and I decided that if something didn’t happen within a year to jack me up that I was going to find something else to do. Eight months later Buck White called me. They wanted more of a country band. Their banjo player had quit so with that it gave me a wide open space to work with. They were great and I could do almost anything I wanted.

I wanted my main role to be backing up vocals and also to do lots of solos. I stayed from January, 1979, to the middle of 1986.

Some people think your leaving the Whites was a mistake. Any regrets?

It was a major decision for me. I didn’t quit the Whites. I quit the road. It was the end of a two year battle for me. Just too many things. I was cooling off. You live by what happens to you on the charts and there’s nothing rational about the record business. Emotions go up and they go down. You can’t form relationships because most people in your life you meet for fifteen minutes. It’s not real to go out and play with a 100 plus temperature. I was changing and setting priorities for the first time and I needed to deal with my personal life.

Still no regrets?

None at all. I like sleeping in the same bed every night and watching my kids grow up.

Being on the road all the time makes you a different person doesn’t it?

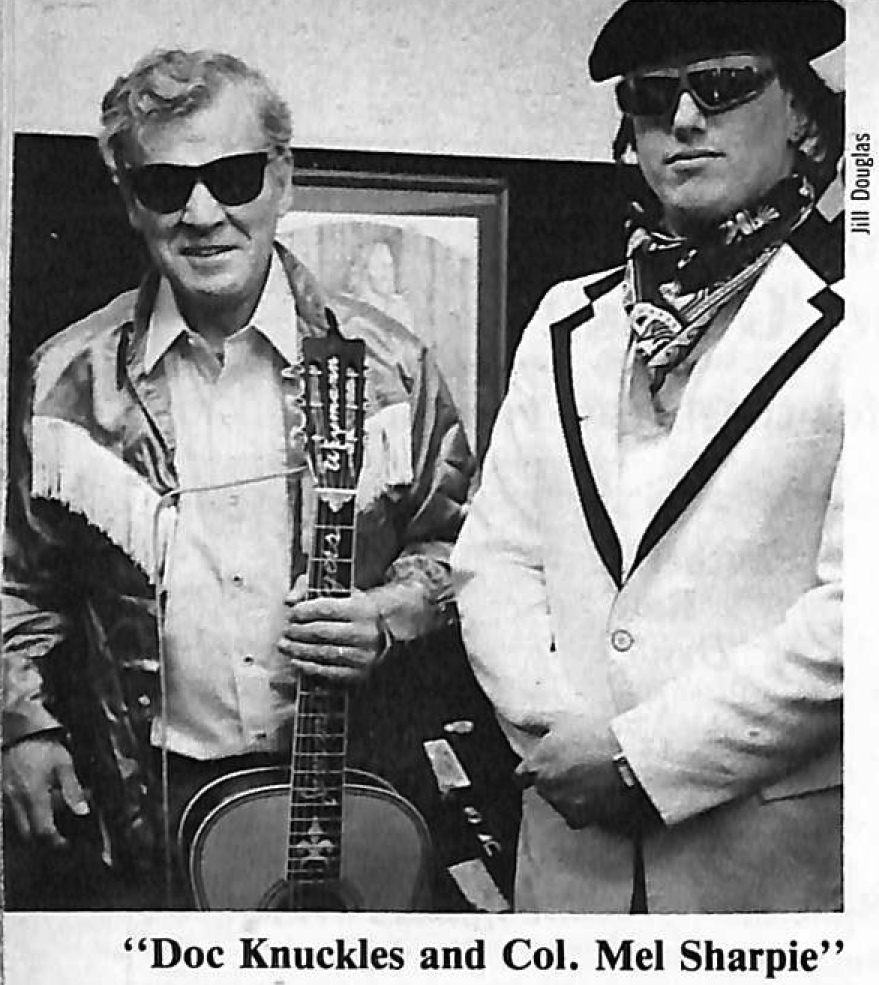

It sure does. I’d feel it coming over me when I’d get off the bus and go out to talk with somebody. They always knew me but I never knew them. So I’d immediately shift into Jerry Douglas, White’s band member or Jerry Douglas on the road. It’s strange to have so many good friends all across the country with their names and faces running together. You start getting superficial. I could see it coming and I just didn’t want to be that way. I wanted to see what it’s like to live a normal life. To have a personal life. To spend time at home with my wife, Jill. You know I have a son, Grant, from my previous marriage and Jill has a son, Patrick. We’re hoping to expand our family one of these days. The road musicians’ schedule just doesn’t allow a family man to be home enough. [Editor’s Note: On January 22, Jill gave birth to a little girl—Olivia Elizabeth French Douglas.]

During all your band picking experience, what was the high point or single exceptional band experience?

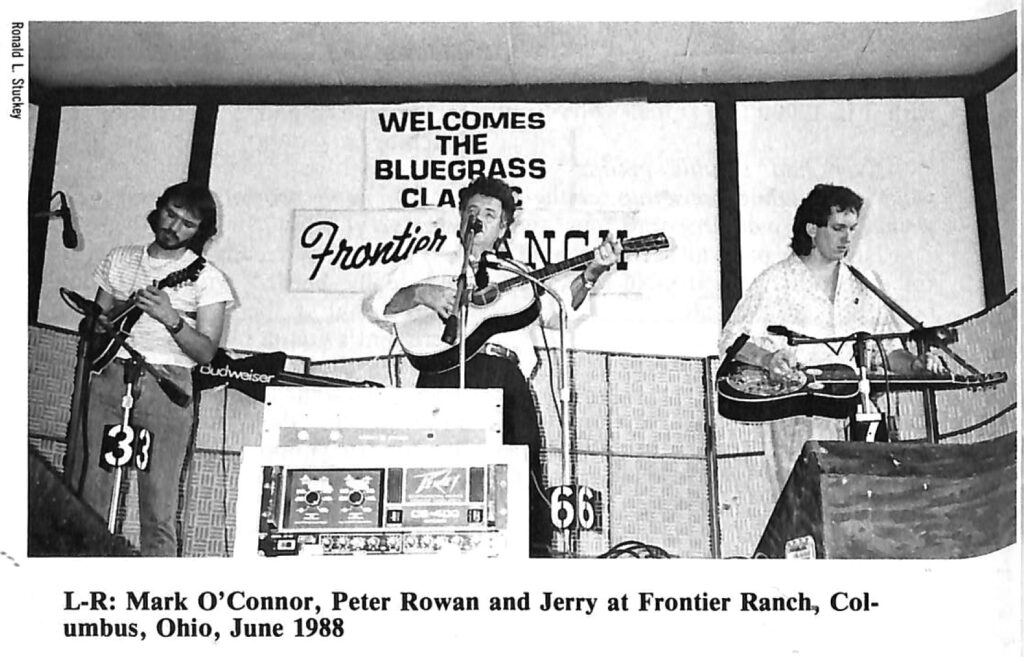

It had to be playing in Japan with J.D. Crowe—Bobby Slone, Tony Rice, Ricky and me. We were like the Beatles over there. Treated like royalty. Also, I’ve had some really cool experience with Buck and the girls on foreign tours. One was a South East Asia tour through Thailand, Burma, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Greece and Portugal. Two years ago Mark O’Connor and I put together a tour behind the Iron Curtain. I’d love to go back now that things are relaxed.

Even though you’ve had extremely good experiences, it has been better in other countries?

A lot of it is “Anything Western,” especially in countries behind the Iron Curtain. You’re elevated to “hero” status. The people are starved for the music. You do a lot of good when you go to these places. You’re an ambassador.

We keep getting told what a bad name we have in other countries but the people prove otherwise don’t they?

They sure do. They tell us they love us but can’t do anything about it. They’re ruled by their leaders and that’s the way it is all over the world. No matter what you hear.

What are your thoughts on public appearance performances being the same as the recording? Some musicians seem to be saying, “Here’s what I want you to hear.”

Some of it is because of different bands for recording and “road” bands. The “road” band is saying, “I didn’t record it that way, I’ve got my own way of playing it.” I think the successful country acts now do stick pretty much to the recorded version. That’s the very reason I went on the Gary Morris Tour. Mark O’Connor and I were on the record and the tour was to be the same as the record.

I believe the customer is getting short changed if he doesn’t hear what he first heard on record.

Sure, that’s why he bought the ticket and if he doesn’t hear what he paid for he’ll be disappointed and won’t come back.

Other comments?

Bluegrass is somewhat different in that much of it is based on improvisation and most bands are the same on record and on the road. So the customer hears about the same thing every time and is satisfied. I used to play everything different until with the Whites, I had to lock in on “You Put The Blue In Me.” How many thousand times did I have to kick it off the same way. I had to because that’s what everybody keyed on.

Did you have trouble with this discipline?

Well yes, but I was able to make subtle changes to the solo. There’s good and bad in playing the same things over and over. If you play the same each time you refine it and it gets better and better. After you’ve played it so many times you have everything under control. It’s smooth and just simply a better performance than, say, on record.

I first noticed something on one of the [bluegrass] Album Band cuts. You put a note on top of a Tony Rice voice note. I’ve tried it and it’s weird. What gives?

It’s a harmony thing. You know how vocal a Dobro is. Fade a note properly into the mike and it will sound like a vocal note. It’s there just like somebody sang it. I do that a lot. I just thought that here’s a way I can do something along with the vocal and step on the vocal but not distract.

You’ve done a lot of instrumentals. Have you written any songs?

Nothing anybody’s ever seen. I did a long time ago.

Your singing?

I’ve done parts with different bands over the years, baritone with Boone Creek. Never sang with the Whites. They didn’t need it. I go out sometimes with Maura O’Connell and Russ Barenburg and we do a trio thing.

On session work — I read somewhere that everything Jerry Douglas put on tape was usable. When do you first hear or see the material to be recorded? How do you learn it?

It’s all part of being a good session player. You must be able to learn fast. We have charts to get through the song but you need more than that. You need the words, the emotions, the dynamics and how to react to the words.

What time is involved in doing a couple of songs for an album?

Sessions are set up on a three hour schedule. Like 10:00-1:00 and 2:00-5:00. You go in and work on the tracks. I usually work on an overdub. Sometimes you can get what’s needed in a few minutes and sometimes it can go on for hours. I worked three hours yesterday on one tune with the lap steel.

You don’t ever hear it before you get there?

No, but you’re lucky when you overdub because everything else is there. I’ll listen to it with the producer. We’ll talk about what’s needed and I’ll make notes. Then I’ll do a first run through. We’ll listen back and usually do one or two more. Sometimes the finished track will be parts of all the takes. You always have to do it like you were there when the whole thing was recorded.

That level of professionalism I think is beyond the comprehension of most pickers. How many people in the world get to this level of being a good Nashville session player?

I guess it turns into a business. First, you start off doing it because you love it. If you’re lucky like me, it turns into a business and you continue to love what you do. My work and what I love to do has been the same all my life.

You’ve played on so many albums. I’ve seen a lot of your awards but what stands out for you?

I’ve had the feeling on a number of albums that this is the best I ever played. That’s a great feeling. I’ve had more fun on the one’s that were not commercial successes. The one that sort of rounds it all out for me is the record I did with Bela, Sam, Mark and Edgar. I think it is a real statement from me and from them. It’s my peers and my friends all at the same time. We, with each other, wrote the whole thing and made it together. You can hear a piece of everybody. I’m, really proud of that record. It’s called “Strength In Numbers,” (MCA 6293).

Did you ever find yourself in one of these picking duels?

No. I’ve always been pitted against [Mike] Auldridge. We’ve played on stage together and we recognize we’re different players. I love to hear him play and he likes my picking. We’ve never fought over it but we’ve just sort of let people think we have just to egg it on.

I’ve seen a few duels and they were always engineered by others.

Yeah. It’s like gun slinging. I’d never get into it. I’ve seen plenty of it especially among banjo players.

Some people have the idea that Nashville pickers like you get free instruments all the time.

It happens, but not often. Most of the time the picker has to pay something. Usually the cost of the materials anyhow. I think it’s in bad taste to take free instruments just to sell them later on.

I just watched some of your new Homespun instruction tape. How did this come about?

I’ve had a lot of people wanting me to do a book or tape. I’d heard it took so much time and I didn’t have it. I finally decided to do the tape and it wasn’t much trouble at all.

You are in your early thirties. Many of the great innovators have worked at their music all their lives. In your twenty-plus years of picking you’ve probably expanded your art as much as most. You were nominated five times for “Instrumentalist Of The Year” in the CMA awards. I see awards all around and God knows what else. With all this, what are you going to do for an encore?

First, I’m not into just one kind of music. Secondly, I’m going to continue to refine it. I could just go along on what I’ve done but I’ve always built on what I’ve done. I expect to go on that way.

As an older person who has enjoyed acoustic music for years and observed much change, I’m concerned. You know the pop music of the ’50s and ’60s disappeared into New Country; with all this meshing and fusing do you see this happening to bluegrass?

They’re all related and I think after a certain point you have to stay in touch with where you came from. At the same time stay up with what’s real. Stay in touch with your roots and trust what got you there.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I m John E Douglas and the sun go hare I go?

Jerry seems to be an amazing human being as well as player!