Home > Articles > The Tradition > The Industrial Strength Bluegrass Project

The Industrial Strength Bluegrass Project

Traveling the Hillbilly Highway

On January 29, 2021, Smithsonian Folkways, the nonprofit record label of the Smithsonian Institution released “Readin’, Rightin’, Route 23.” The song is performed by Joe Mullins & The Radio Ramblers, but was penned and made popular by Betsy Layne, Kentucky native Dwight Yoakum. “Readin’, Rightin’, Route 23” is the first single from Industrial Strength Bluegrass and sets the stage for the historically and culturally significant project aiming to tell the story of the golden age of bluegrass music in southwestern Ohio. While it presents the importance of southwest Ohio as a hotspot for the genre, it also does something a bit more—introduces listeners to the migratory history of Appalachian people, and how their strong connection to the hills, hollers and coalfields intensified the production of bluegrass music.

Background

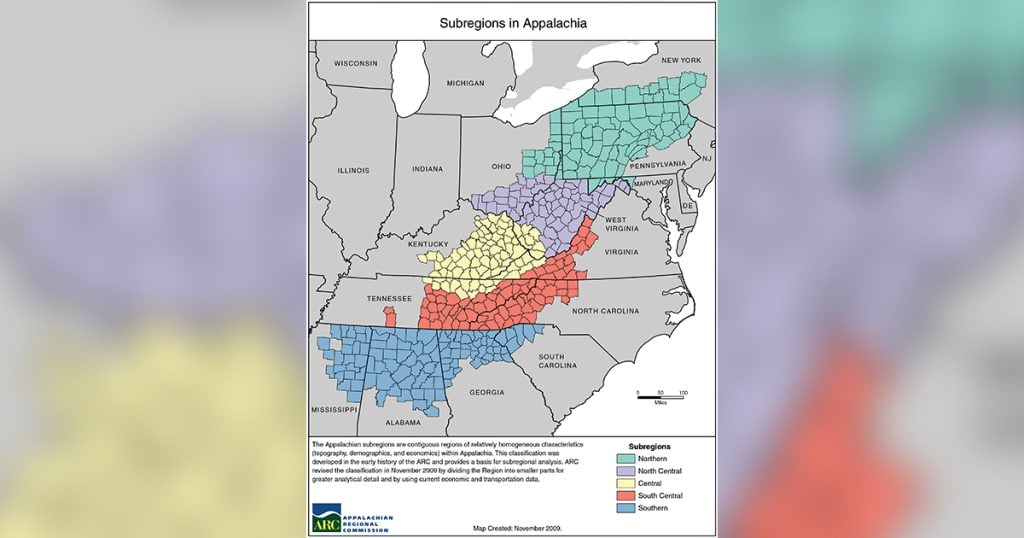

Appalachia is a place of dualities and contradictions. Geographically, scholars rely on the federal definition of Appalachia, provided by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). This massive area includes 420 counties spanning 13 states from Mississippi to New York. Industrial Strength Bluegrass prompts listeners to think more broadly about the geographic and cultural touchpoints of the “high lonesome sound,” focusing on the common experiences of being forced to leave the place you call home.

The Appalachian region is a place both real and imagined. Most agree that the region was named after the Appalachee (also spelled Apalachi) tribe encountered by Spanish explorers and conquistadors in what is now Florida. Contrary to most assumptions, the region was not isolated or separated from the greater US, rather the idea of Appalachia as a place “different” from the rest of the country emerged via local color writing in the 19th century. These writings portrayed romanticized notions of a place far removed from the Civil War and slavery, and also portrayed a “barbaric” land of “lazy hillbillies.” As early as 1904 a film depicting a stereotypical moonshiner was directed by Wallace McCutcheon and filmed in New Jersey.

The longevity and unchanging characteristics of the hillbilly stereotype are stunning. The industrial era in the states brought “coal camps” and mill towns to areas rich with resources to be extracted. The boom-and-bust cycles of extractive industries, lack of individual land ownership, and the promise of “jobs in the city” were all contributing factors to Appalachia’s massive out-migration from the 1940s to the 1960s. As people from the region moved to urban areas seeking work, stereotypes returned with vigor. This experience and distinct time period have been documented in songs such as Yoakum’s ode to Route 23, Steve Earl’s “Hillbilly Highway” and “Detroit” by Kentucky native Tyler Childers. While studies show Appalachians accounted for only a quarter of southern whites who migrated to cities during this time, white Appalachian migrants had a dramatically different experience than white migrants from the general south. In comparison, Appalachians had significantly lower incomes, lower levels of education, more female-led households, and fewer opportunities to return home. Very few studies comparing out-migration challenges that incorporate race have been conducted. While Appalachian out-migrants experienced specific challenges due to the perpetuation of stereotypes and the belief that “hillbillies” simply “didn’t work hard enough” the resilience of out-migrants has also been documented in regional literature, such as Harriette Arnow’s The Dollmaker published in 1954. It was also during this time that bluegrass, a notable departure from hillbilly and barn dance music and performance, was officially named and solidified as a genre.

Industrial Strength Bluegrass reflects the stories of mountaineers miles from home, who leaned into traditional cultural practices to strengthen bonds and create new communities in the city. From cooking traditional mountain dishes, to handicrafts, to music, out-migrants forged an intense sense of Appalachian identity in urban centers. Radio programs carried familiar Appalachian accents into the homes of out-migrants, including the voice of Paul “Moon” Mullins, Joe Mullins’ father.

The close connection of personally experiencing the impact of out-migration and an intense love for bluegrass music are apparent in Joe Mullins’ dedication to the Industrial Strength Bluegrass project. In the “Producer’s Note,” he shares:

“While I am a native of the Miami Valley of southwestern Ohio, my family tree grows right out of the hillsides of eastern Kentucky. When I was a youngster, our family was one of those that left our residence in Ohio to go ‘home’ any weekend my dad wasn’t working as a bluegrass fiddler, broadcaster, emcee, or concert promoter. My dad (from Menifee County, Kentucky) and mom (from Lawrence County, Kentucky) migrated to Ohio in 1964. However, 20 years later, my parents still referred to Kentucky as ‘home.’ I grew up near the factories that employed thousands of people just like my parents, and alongside hundreds of second and third generation Appalachian transplants.”

Industrial Strength Bluegrass offers a snapshot of that particular moment in history.

Recording

The project began as an effort to preserve and celebrate southwest Ohio’s musical influence. A team including Joe Mullins, members of Miami University, and Fred Bartenstein took on the task of researching and archiving the history of bluegrass music in southwestern Ohio. From this fruitful work and a successful lecture series, the book, Industrial Strength Bluegrass emerged. It was Joe Mullins’ idea to produce a compilation album, recreating songs important to the history of the area featuring some of today’s most highly applauded bluegrass artists.

The 16-song collection produced by Mullins was no easy task. His son, Daniel Mullins, served as the associate producer and provided liner notes for the project. In all, the process to produce the album took two and a half years. Joe Mullins recalls:

“The Radio Ramblers were working Bean Blossom with the Seldom Scene one day in 2018. Ronnie Simpkins works with Smithsonian Folkways and I chatted with him about the idea. I met with label director John Smith a few months later in Raleigh during IBMA’s World of Bluegrass. By December, Miami university created a plan to provide funding for the album. I began conversations with many of the artists during 2019 and the first sessions were in Nashville in November.”

Shortly after a recording session in March, the international pandemic halted the ability to travel and record as easily. Despite the challenges of COVID-19, small recording sessions resumed in late June. Navigating the virus was difficult as it impacted the availability of performers and studios. Persistent and determined to finish the project strong, Ben Isaacs, Mark Capps and Paul Harrigill (with the assistance of at least a dozen other engineers and recording technicians) all stepped up as project engineers. And against all odds, the team had everything finalized and mastered by Fall 2020. Mullins sees the time apart as a silver lining, saying: “I think you can hear and feel the energy on this album because everyone was playing hungry! We hadn’t been able to perform for months!”

The songs were selected by Joe and Daniel Mullins, with Joe considering southwest Ohio’s musical history and Daniel listening for connections to today’s audience and artists.

“We had huge lists of potential artists and possible song choices. We assembled songs that tell the story without including songs that have been covered too many times in other recordings. Some of these songs are what I call jam session favorites but very few recorded versions of them have been produced since the originals. Stone Walls and Steel Bars, 20/20 Vision and Suzanne- all strong standards. Others are more obscure but really tell the story of the culture among the first- and second-generation Appalachian transplants- The Rolling Mills of Middletown, Life’s Other Side and We’ll Head Back to Harlan.”

The tracks, in whole, present a journey, with the first track moving up Route 23 and the final song returning to Harlan (Kentucky), reminding the listener that nothing happens in a vacuum. The vocals of Morgan Sexton and Roscoe Holcomb, echoes of barn dances and gospel quartets are all traced into the lineage of the songs. And while the project unquestionably presents southwest Ohio’s legacy, the Mullins’ also looked beyond Ohio for artists. They chose to feature highly awarded and nationally known musicians who recall and invoke the aesthetics of the original performers, whether it be picking styles or repertoire. These details are all described in depth in the liner notes. There are, of course, Ohio natives in the mix, including Grammy award winning Jerry Douglas, Dayton mandolinist David Harvey, Ben Issacs, Adam McIntosh of the Radio Ramblers, and Chris Davis of the Grascals. The liner notes, written by Daniel Mullins, present a history for each song, connecting it firmly to performers, studios, or songwriters from the area and branching out to highlight larger contributions to the genre. Notably, Daniel Mullins brings attention to Philip Paul’s collaborations with Syd Nathan. In all, the magnitude of the artists collaborating on the project reflects the collective respect and fondness for the Ohio scene and the shared emotional residue of Appalachian out-migration.

Looking Ahead

For Mullins, this project is “a lifetime labor of love.” Growing up surrounded by bluegrass history in the making, he recalls listening to the artists represented on this album through his father’s radio program. As an internationally distinguished performer, he has learned that people across the country and around the globe have become passionate, lifelong bluegrass devotees because of much of the music created right in his community.

Perhaps it is not so much that the hillbilly highway turned bluegrass “music to a movement…” but that by focusing on the musical history of a single place, we find that music is created out of movement, exchanges, and relationships. Route 23 is still running both ways with new challenges facing the region’s inhabitants, immigrants and out-migrants. Music continues to be created and shared by migrant and displaced populations throughout the region around the globe. Sound doesn’t stop at borders, but it can, if for a moment, take one back home, as shown in Industrial Strength Bluegrass.