Home > Articles > The Tradition > The IBMA Hall of Fame Class of 2024

The IBMA Hall of Fame Class of 2024

Alan Munde, Katy Daley and Jerry Douglas Talk About Receiving the Good News

Music awards are a good way to capture a moment in time in an industry. While always subjective, with the nominations and results debatable, the positive side of awards and award nominations is that it gives music lovers a chance to hear the names of some of the best artists in a genre who are creating noteworthy music in a given period, while hopefully bringing attention to everyone who plays the music as a whole.

Being inducted into a Hall of Fame, however, is a different matter. It is an honor that reflects a body of work, a career-spanning award that acknowledges the full story of an artist’s years of productivity, creativity and impact. Halls of Fame usually begin by paying tribute to the founders of a music genre or art form, and then they honor those that follow who leave their mark and push the music forward.

In the bluegrass world, the $15 million dollar Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Owensboro, Kentucky, has proved to be an impressive interactive and multi-use facility that brings in visitors from literally around the world. On the walls of that building are the individual plaques that tell the story of each of the IBMA Hall of Fame’s members and bands, and in 2024, three additional displays will appear that will highlight the careers of Alan Munde, Katy Daley and Jerry Douglas.

Every year, Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine enjoys talking to the new class of Hall of Fame inductees soon after their induction announcement to get their reaction to the good news, and to hear their thoughts on what they have accomplished during their careers and how that story has unfolded over time.

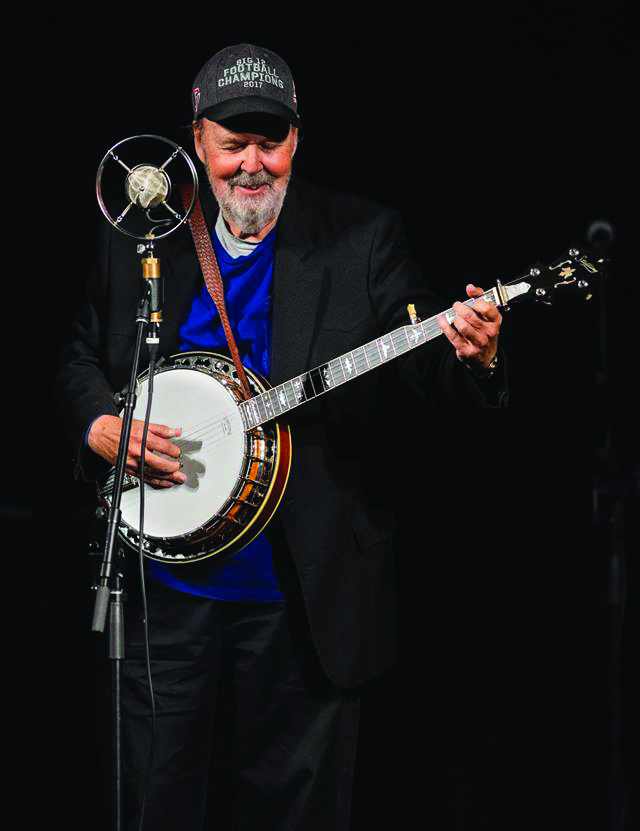

Alan Munde

Alan Munde represents the part of bluegrass music that evolved and rose up outside of the hills of Kentucky, the Midwest and the Appalachian Mountain region. Munde was born and raised in Oklahoma and his banjo work has become legendary.

A proponent of both the Earl Scruggs style of playing the instrument as well as the Bill Keith-influenced melodic style of picking the banjo, Munde is already a member of the American Banjo Hall of Fame and a winner of the 2021 Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass Award. Just as important, he spent 20 years on the education side of the genre by teaching bluegrass and country music at South Plains College in Texas.

Here, we will talk about some of the musicians that played a key part in Munde’s evolution as a musician, beginning with Byron Berline. Back in the early 1960s, it was the end of the folk boom that exposed Munde to the world of the banjo and that time period sparked his desire to learn how to play that instrument as well as the guitar. Eventually, he came across the Foggy Mountain Banjo album released by Flatt and Scruggs and that opened his eyes to bluegrass music genre. His biggest piece of luck, however, was enrolling into the University of Oklahoma where he met fellow student, the great fiddler Byron Berline.

“I met Byron in college and we hung out together and played a lot of music together,” said Munde. “I’d go to fiddle contests with Byron and back him up. He was a great player from day one. Also, before the age of the internet, you made connections with actual people, and Byron was sort of my connection to the outside bluegrass world. By the time I met him, he had recorded an album with The Dillards, had been to the Newport Folk Festival, and he had met Bill Monroe and Bill Keith. He also acquired live recordings on reel-to-reel of The Dillards, The Kentucky Colonels and of Bill Monroe with Bill Keith in the band, and those recordings were exciting to listen to, so our friendship was a real gateway into this music.”

Eventually, Munde would become a member of the band he would perhaps be best known for in The Country Gazette. “The Country Gazette started in late 1971 with Byron Berline and bassist Roger Bush wanting to get a group together and they brought in Kenny Wertz on the guitar,” said Munde. “They also wanted Herb Pedersen to play the banjo, but he had just left The Dillards and didn’t want to be in a group situation. So, Byron got in touch with me and asked me if I would be interested. I was just leaving Jimmy Martin’s band at that time, so in early 1972, I moved to California and joined up with Byron, Roger and Kenny in the Country Gazette. They already had a deal with the United Artists record label by that point, so we began to play and record together right away.”

Moving to California was not as big a deal for mid-continent musicians like the Dillards and Berline and Munde, compared to the pickers who lived in the eastern half of the country. But coming from Oklahoma, Munde still viewed Los Angeles as big and exotic and once he found an apartment in a four-plex in North Hollywood, it became his home base until 1975. Then, the West Coast members of the Country Gazette, Berline, Bush and Wertz, left the group and Munde moved back to Oklahoma where he continued the band with future Hall of Famer Roland White.

Munde talks about his two-year stint with Jimmy Martin. “Jimmy Martin was strongly melody-oriented in his approach to bluegrass, and he was also about having a musical idea that you present to the listener in as clear a way as you can do it,” said Munde. “One of the big complaints about the banjo in general was, “I can’t tell what you are playing.” For example, there was Bill Emerson’s song ‘Theme Time,’ where a lot of people might approach it by playing some licks in the key of G and then it goes to the key of F, and then it goes back to G and then D, and you play through all of those changes with a bunch of riffs.

“But, Jimmy had a really specific melody that he wanted in that tune and he would use his voice to sing the notes he wanted to rise to the top of my banjo playing, and I would try to reproduce those notes as best as I could,” continues Munde. “Jimmy was influenced by a lot of people, including Chubby Wise and Chubby’s approach to playing songs. So, I think that, for Jimmy, instrumentals were more song-like than being just a tune full of licks. Every song we played had an idea to it and your job on the banjo was for certain concepts to stand out amongst the usual banjo rolls. But, I wasn’t a very mature listener or student at that time, so a lot of the things he talked about musically I wouldn’t fully appreciate until later.”

Meeting Sam Bush… “When I was still in college, and Byron was two years ahead of me and had already left, one day I went to a folk music festival in Mountain View, Arkansas, which was the only gathering then that had any semblance of bluegrass players at it,” said Munde. “The person I met there who was from Kentucky was Courtney Johnson, who was playing the banjo with a bunch of his friends. We played some fiddle tunes together and then Courtney went back to Kentucky where he told Wayne Stewart and Sam Bush about this banjo player he had met in Arkansas who was from Oklahoma who could play in the melodic style that Bill Keith had made popular.

“So, later on, Wayne got in touch with me and said we should all meet at a fiddle contest near Kansas City,” continues Munde. “That is where I met Sam Bush, who was only 15 or so at that time. We played music together that whole weekend and we decided to put a group together called Poor Richard’s Almanac. So, after I graduated from college, I moved to Hopkinsville, Kentucky. But, soon I got my draft notice and had to move back to Oklahoma.”

On Roland and Clarence White…“Roland was a great friend to anyone in Nashville who played bluegrass music, and because of that, he was sort of the godfather of bluegrass music there at that time, and I mean that in a positive way” said Munde. “For anybody that came to town that played bluegrass, Roland would shepherd them through and helped them out any way he could. Eventually, after I went out to California to join the Country Gazette, Roland left Lester Flatt’s band and his brother Clarence had left The Byrds so both of them were out there as well, trying to get something going. Clarence lived out in the desert north of LA in Lancaster and we would go out there and jam and Clarence was a pretty spectacular player.”

Munde’s association with Clarence White would lead to tours of Europe and elsewhere with Roland, Clarence and their brother Eric White, who were billed as The New Kentucky Colonels, and the result of that trip was all four of them performing on the Live In Sweden album. Munde would also find himself sharing a bill with Gram Parsons, Emmylou Harris, Gene Parsons, Sneaky Pete Kleinow and other great artists of that time period who were a part of the Hot Burrito Revue package tour.

Munde would also be around when Clarence White unfortunately died in that infamous roadside accident in 1973. “Right after we got back from that trip to Europe, Clarence was working on his solo album and we had been in the studio working on some cuts,” said Munde. “Roger Bush had rented a space down at the beach and invited me down there to hang out with him and his family. While there, I remember Roger’s wife at that time running down from the cabin and telling us the news that Clarence had been killed. Oh man, it was shocking. Very much so.”

Munde is thrilled about his induction into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame.

“It is a huge, big dang deal for me,” said Munde. “I feel very fortunate to be thought of next to all of those people already in the Hall of Fame, because they are all fabulous musicians. I got an email from IBMA Executive Director Ken White telling me about this honor, and my friends and family are very excited about it. I will have my sister and a bunch of friends coming to Raleigh. I will have my own plaque at the museum and they are going to nail it on the wall and it will be permanent, and that has me excited.”

Katy Daley

Katy Daley has been a bluegrass radio host and festival emcee for decades. Her radio show at WAMU in the huge Washington D.C. market, and on the Bluegrass Country website, was legendary. She is the co-host of the Bluegrass Stories podcast along with Howard Parker. Another legacy aspect of her career that she is proud of has been the creation of the Katy Daley Broadcast Media/Sound Engineering Scholarship that is impressively given out by The IBMA Foundation. Daley was given an IBMA Distinguished Achievement Award in 2019

When Daley first heard of her induction to the IBMA Hall of Fame, she just about fainted. “I have worked on a lot of different committees over the years with the IBMA, which I enjoy, and I was getting ready to go on a Zoom call for one of the committees that day and my husband was setting up our tablet to get signed in to the meeting,” said Daley. “Already on the call about an hour early was IBMA Executive Director Ken White, who said, ‘Katy, I have good news and I have bad news.’ I said, ‘Oh?’ He said, ‘The bad news is that you are an hour early for this meeting, and the good news is that you have just been elected to the Hall of Fame.’ I couldn’t breathe. I think my heart stopped, because I certainly wasn’t expecting that. I think I said, ‘Oh my God. I think I’m about to have a really ugly cry, so I’m going to hang up now.’ So, I did.”

What IBMA Hall of Fame inductees may not realize is that after getting perhaps the most important news of their life, they have to keep it a secret until the official announcement is made in July.

“The crazy part is that you can’t tell anybody the news,” said Daley. “That is the worst part of it. After I found out, I’d see my friends and say to myself, ‘Agh! Don’t tell them.’ I was afraid that if I told anyone, they’d take it away from me, so I didn’t tell. But at the time, after Ken said I had to keep the news to myself, I told him, ‘Well, my husband is right here. Do you mind if we discuss it?’ He said, ‘Yes, as long as he doesn’t tell anyone, either.’ So, we did not tell anybody else in our family, and that was very hard to do.”

When Daley was a kid, radio became an important part of her life. “I was born in Washington D.C. but when I was young, our family moved to Japan and then to the island of Okinawa,” said Daley. “All we had there was Armed Forces Radio and some television. There were no television shows to speak of, but every once in a while the Armed Forces Radio would cooperate with the local Japanese TV station and they would broadcast the show 77 Sunset Strip. To make it work, you had to turn the television sound down and then turn up the radio to get the English audio. That was a big deal. Armed Forces Radio was also important because they played the music that was popular in the U.S. at that time, and we were pretty far away from everything. They had a show on there called the Rice Paddy Roundup that I listened to that played country music. Then, one day I heard a song on the show and I thought, ‘Well, that’s not country.’ It turned out to be ‘Pike County Breakdown’ by Flatt and Scruggs. But, I didn’t hear anything in a bluegrass way after that.”

That all changed when Daley graduated from high school and then relocated to the mountains of Western North Carolina to attend her first year in college. “When I moved to Brevard, NC, to go to school, they didn’t call it bluegrass,” said Daley. “There was always a music scene when I was there, and everybody in my dorm played some kind of instrument except for me. Many of the other students came from high schools that were so small that they didn’t have football teams, but they did have clogging teams. On a Saturday night, if you weren’t going out, which I rarely did, they gathered in the dorm and would do what we called back then a ‘hootenanny,’ where they sang or danced or played music. But, I never heard the term ‘bluegrass’ until I came back to Washington D.C. around 1966 or so.”

Once back on the eastern seaboard, Daley finally realized that old-time music and bluegrass were close cousins yet were distinctly different genres. “I found out the difference when I worked as a volunteer for the National Park Service at the C&O Canal,” said Daley. “That was an old canal that used mule-pulled boats and it started about 180 miles away up in Cumberland, Maryland. They would load the boats full of coal and bring it down the canal to Georgetown in D.C., which at that time had a lot of factories in it. My husband and I were volunteers there and we learned to work with mules, which meant two city kids all of a sudden working with farm animals.

“That was a real learning curve for us, but it was great,” continues Daley. “When we were on the boat and telling the visitors about the history of the canal, the Rangers would take a break and play some music. I didn’t play any musical instruments at all, but at the end of the season, the lead Ranger went to the closet and grabbed an open-back banjo and she said, ‘Here, take this home with you and learn it.’ So, I did, and during the era of the use of the canal, the music of the day was old-time and not bluegrass. I found a teacher that showed me the basics, and that is when I became interested in old-time music.”

Eventually, Daley would also learn how to play the bass and would join a band, and that led to her full immersion into the bluegrass side of the ledger. Years later, Daley began her foray into the world of radio. “I first became a volunteer for Gary Henderson’s Saturday morning radio show, where I would spend my days calling up bands and saying, ‘Where are you playing this week?’ and then I would compile the show list and read it on the air,” said Daley. “That is how I got started. Then, they offered me some more time, as Gary was working Saturday and Sunday and then all week on National Public Radio. So, I said, ‘I can try it,’ even though I didn’t even know how to thread a tape machine at that point. But, I learned how to do it and Gary and I split the ten to midnight shifts on weeknights playing bluegrass. Then, once I had my own show, eventually they moved it down to the ‘drive time’ slot, and that was about 1973.”

Looking back over her career in the bluegrass world, Daley remembers the folks that stepped up and helped her along the way. “I really want to make sure and mention Pete Kuykendall,” said Daley. “Pete was the first festival promotor to pay me the same amount of money for being an emcee that the men made as an emcee at his Indian Springs festival,” said Daley. “That was a huge thing to me. I was very surprised when that happened, and I even offered to give the money back. But he was like, ‘What? No. You earned it.’ He was a very good man. There were a lot of people that were very helpful to me, but the most concrete person was Pete. Pete’s wife Kitsy told me that he was brought up by a single mom, and if you look back to when he was alive and ran Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine, a lot of the people that worked there were women.”

As Daley’s radio career grew, there were many bluegrass musicians that believed in her work. “I’d also like to mention John Duffey,” said Daley. “John was quite a character and when you went to see his band The Seldom Scene live, he was very funny onstage and you didn’t take your eyes off of him because you never knew what was coming next. In person, however, he was shy. He was very nice to me and at festivals, sometimes, we would walk around and visit the various record tables and he’d say, ‘Do you have this record? You need to get this one.’ Charlie Waller was very nice to me as well, as were all of the members of the Country Gentlemen.

“Doyle Lawson was also very good to me, so I was very fortunate to have people that were willing to bring me along once I was in the radio business,” continues Daley. “At first, I didn’t have any bluegrass records, so I called up Mike Aldridge and said, ‘Mike, I was wondering if you could come down and do a two-hour interview on the radio about your music?’ He said, ‘Sure.’ Then I said, ‘Ok, great, and could you bring your records?’ (laughs) Mike was such a nice man, and his family even had me over for Thanksgiving one year.”

Jerry Douglas

It would take a book to fully tell the story of all of the things that Jerry Douglas has accomplished during his bluegrass career. The best way to get all of that information would be to research his discography and take in the vastness of his experiences in music, from his solo albums and his over 2,000 studio sessions to his work with various great bands and legendary band mates, to his collaborations with some of the best musicians to ever live on this planet.

What is fascinating about Douglas is that he is one of the very few artists that can be described as having sparked a generation of musicians following their path, due to the innovation they achieved on their instrument of choice. Earl Scruggs spawned multiple generations of like-minded banjo players after his specific three-finger technique of playing the five-string appeared on the scene 81 years ago. Tony Rice was another genius whose guitar playing changed the game and created generations of players that were blatantly influenced by his talent and style.

On the resonator guitar side of the equation, after Dobro pickers like Uncle Josh Graves, Brother Oswald Kirby and Mike Aldridge laid down the foundation, Jerry Douglas came on the scene in the 1970s and encouraged and influenced generations of Dobro players who are still making their mark in the bluegrass world today. As for how Douglas found out that he was getting the biggest honor of his career per his impending induction into the IBMA Hall of Fame, he heard the news in a more dynamic way than what Alan Munde and Katy Daley experienced.

“I was getting ready to go and play with the Earls of Leicester at the Ryman Auditorium and Ken White came down the steps with my manager Brian Penix and a whole bunch of other people like a big cloud,” said Douglas. “Then, Ken said, ‘You’re in.’ I said, ‘I’m in what?’ He said, ‘You’re in the Hall of Fame.’ And right after I heard that, I had to go play onstage immediately afterwards. For that whole first set, I was all to pieces, trying to figure out, ‘What did he just say?’ I was not, in any way, expecting that. I knew I was on the ballot, but you can be on the ballot for years, and be there with other musicians who are equally if not more qualified. For some reason I thought, ‘That honor is for guys that I went to see play when I was a kid. That’s what the Hall of Fame is for.’ Now, when I see kids are coming to see me play, I realize they are having the same experience that I had as a kid, only in a different era.”

Douglas described the experience as like being sent into the cosmos with the initial news of making it into the Hall of Fame, and then being quickly brought back into reality when told that he couldn’t tell anyone about it. In that moment, he soon found himself surrounded by his friends and band mates in the Earls of Leicester and was playing with them in real time, and yet he could not say a word about it.

“It was kind of like that joke about the road manager, the stage lighting guy and the sound guy that found the Genie in a bottle,” said Douglas. “They rubbed the bottle and the Genie came out and said they each had a wish at their command and the lighting guy says, ‘I want to go to Las Vegas and get married to a beautiful woman,’ and bam, he was gone. The sound guy then tells the Genie, ‘I want to go, too. I’ll be his Best Man,’ and bam, he was gone. The road manager then walks up to the Genie and says, ‘For my wish, I want those guys back here in five minutes for a sound check.’”

Once the news had sunk in, however, Douglas’ thoughts became more retrospective. “This award is the big one, as far as I’m concerned,” said Douglas. “You know, I’ve never made or played music for awards, but this is a ‘you’ve stuck to your guns’ kind of award, trying to improve everything per the music and the players who play it and on down the line. After the news was announced, the messages came in from everywhere, from all over the place. I heard from basically everybody that I know.”

While standing there, about to go onstage, Douglas’ thoughts raced and bounced in many different directions. “I thought of Bill Emerson and Charlie Waller right away,” said Douglas. “They were in some of the first visuals that came into my mind after hearing the news. And then, days later, I had to play at the ROMP Festival in Owensboro with the Bluegrass Hall of Fame and Museum right there, yet I couldn’t tell anybody, other than some of the folks at the museum that knew. It was crazy, because I walked in the museum and there is one of my Dobros in the middle of the room. Then, over to the right is a room with photos of some of the first-ever bluegrass festivals and in a picture of Ralph Stanley’s festival from 1973, it shows the old stage down in the bottom and on the stage you see me, Bill Emerson and Charlie Waller. That was my first day as a member of the Country Gentlemen and Bill’s last gig with the group before he went to join the U.S. Navy band. Then, on the next wall over, there was a picture of J.D. Crowe and the New South taken on the first day that I ever played with them as a band member. All of that was on those two walls and it shocked the heck out of me. I thought, ‘Whoa, this stuff is getting a little too close here.’ It was just a series of wild coincidences that was happening right in front of me.”

The first folks that Douglas wanted to talk to about his induction were his wife Jill and his friends Allison Krauss, Béla Fleck and Sam Bush. What is really special about this occasion, however, is that his mom and dad, John and Autha Nae Douglas, are still alive and doing good and ready to see their son enter into the Hall of Fame at the 2024 IBMA Awards Show in Raleigh, North Carolina.

“My Dad just went crazy,” said Douglas. “When I told him that they announced it on the radio earlier that day, he said, ‘So, I can tell people now?’ And, I said yes. My Mom said, ‘I thought you were already in that.’ (laughs) My Dad told me that he was very proud of me, and that he knew I would be in there one of these days. So, my parents will be there, and my wife and kids, and my brother Brian is coming in and more, so it will be a special night.”

For anyone who enters any kind of hall of fame, it usually takes place later in life so very few inductees are lucky enough to have their parents with them as it happens. What is special about the father and son team of Jerry and John Douglas is that Jerry was raised while being around his father’s bluegrass band, which were called John Douglas and the West Virginia Travelers. Though Jerry grew up in Warren, Ohio, after his parents moved there for work, John’s band name proudly pays tribute to the whole family’s Mountain State roots.

“My Dad is 92 years of age, so he got to see it happen, and this all happened because of him,” said Douglas. “He was the one that got me interested in bluegrass music. Otherwise, I might not have ever known about the music at all. If he hadn’t been a guitar player and did not have a band, and if I didn’t have that kind of music around me when I was growing up, I wouldn’t have done anything like this with my life. So, it was great to tell my Dad. The best thing for me about this whole thing was to be able to tell my Dad that I was going into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame.”