The IBMA Celebrates 40 Years as a Bluegrass Music Organization

We Interview Some of the People Involved with All Stages of the IBMA’s History

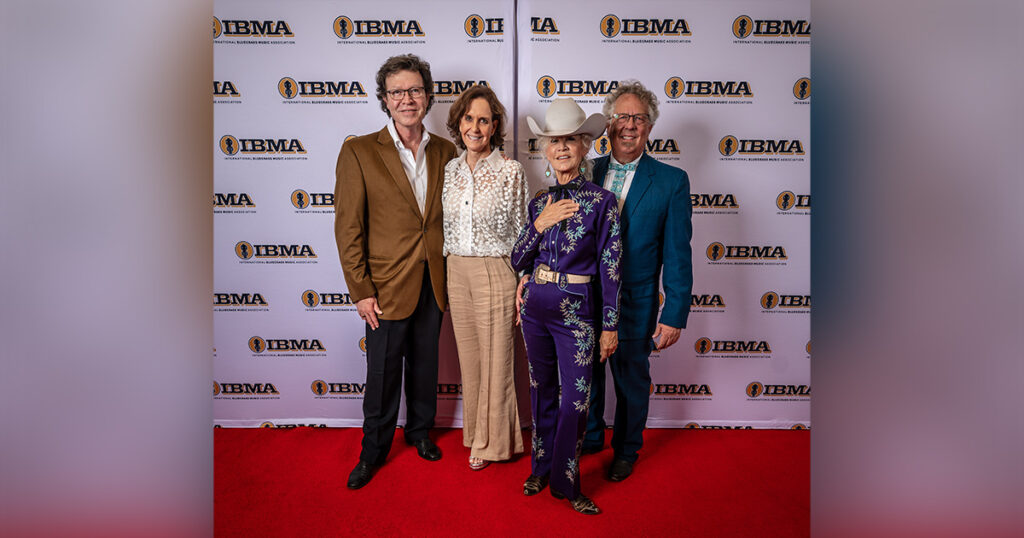

Photos Courtesy of IBMA

It was in 1985 that the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) was officially formed, which makes 2025 its 40th anniversary year. In this article, we are not going to do a deep dive into the logistics and details that surrounded the formation of the organization, but instead, we will interview some of the folks who have been involved with the IBMA during its early years, its middle years, and currently as the bluegrass genre heads into new territory.

Amazingly, when looking back, four decades have somehow gone by since the creation of the IBMA organization. Back then, the first Board of Directors included businessman and bluegrass lover Terry Woodward (who would go onto be an essential part of the building of the $15-million Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum that is located in Owensboro, Kentucky), booking legend Keith Case, Eugenia Snyder, Mary Doub, Barry Poss, Milton Harkey, Larry Harrington, Art Menius, Larry Jones, Allen Mills and Bluegrass Unlimited own creator and long-time Editor, Pete Kuykendall.

In a recent interview with Art Menius, he describes what the goals were in those formative years when he was the part-time Executive Director of the IBMA. “It was Lance Leroy who first put out the call for two dozen or so of us to come together for a meeting in Nashville,” said Art Menius. “The goal back then was to pull the industry together. A lot of folks at that time felt that a generational transition was happening, that young folks had left bluegrass music, and it was ‘circle the wagons’ time in the industry. Richard Harrington of the Washington Post and others wrote articles during that period about how bluegrass was dead. My dad-blamed friend from Pittsboro, Snuffy Smith, said that, ‘There are only like ten thousand bluegrass fans in the world and they all go around to the same festivals.’ So, many of us thought we had to pull together to keep alive, at least as far as it being an actual business and not just a music genre.”

Ultimately, the plan was to unify the industry and to create a convention where everyone could meet, and eventually to create the Awards Show that would follow five years later. “We wanted to create these events to publicize that there was a bluegrass industry and that there were people who did go to bluegrass shows and bought bluegrass records,” said Menius. “Fortunately, the Simmons Research organization still tracked bluegrass music in those days, and we acquired a bunch of important data about the genre from them. This data indicated that there was a thriving market for the music. It wasn’t easy to get folks from the many different areas of bluegrass music to come together under one umbrella, but it was probably easier to do than we imagined at the time. There were not that many holdouts who were opposed to the formation of the IBMA or were sure that the idea wouldn’t work. Many folks were simply worried if they would have gigs booked five years down the road, and they thought the formation of the IBMA might do some good. As Bill Monroe said, ‘Well, I don’t see no harm to it.”

By 1986, the newly formed IBMA hosted its first rudimentary convention in Owensboro. Some of the early supporters of the IBMA included the Society for the Preservation of Bluegrass Music of America and Jo Walker-Meador, the Executive Director of the Country Music Association, who gave the folks at the IBMA a copy of that organization’s bylaws, which were adapted to fit the IBMA by Menius and Randall Hylton.

One recurrent theme of the formation of the IBMA was the creation of the Trust Fund, which was based on the Grand Ole Opry Trust Fund that was set up to help musicians in need. “It was Sonny Osborne who pushed for the Trust Fund,” said Menius. “For Sonny, the IBMA Trust Fund was more important to him than anybody else. If it wasn’t for Sonny, the Trust Fund probably would not have happened. Sonny worked to make the Trust Fund a reality and got artists to come and play the IBMA Fan Fest, which funded it at the time.”

Right after the IBMA was created, Pete Wernick joined the organization the next year. “I was not a Founder of the IBMA, but I was called in to run for an office in the organization in 1986 and I became its first President,” said Pete Wernick, who not only runs the acclaimed Dr. Banjo Jam Camps, he is also about to be inducted into the IBMA Bluegrass Hall of Fame as a member of the band Hot Rize. “The goal of the IBMA was to be a trade organization, and I had to make public statements almost at once while in the role as President, so I distilled it into a two-word phrase, which was ‘Help Bluegrass.’ That had nothing to do with changing the music in any way, but instead it was about serving bluegrass and helping the genre to be more popular, and to help facilitate better communication throughout the bluegrass community, which included mailing lists and other methods of interaction. One of the most important things that we did was to create the convention, for example.”

The overall goal, of course, was to publicize bluegrass music as a truly unique form of American music that is hopefully growing and played around the world. “In the 1990s, I was made the Chair of the Marketing Committee, which gave me a different way to work to enhance the publicity of the music,” said Wernick. “I did some research and found some data on the popularity of bluegrass music, which included the U.S. Census of 1980 that ranked bluegrass tenth on their list of music styles that they defined at the time. Bluegrass was even with jazz music on the list. Jazz music, of course, due to folks like Wynton Marsalis and others, is pushed by very well-funded organizations, and rightly so. But, on the other hand, the bluegrass genre has more radio shows and festivals featuring its music, by far. These days, bluegrass is lucky to have organizations such as the Junior Appalachian Musicians program that teaches young folks how to play the music, and the California Bluegrass Association also has a large instructional program for kids run by Kimber Ludiker as well, as do many other instructional outlets found in other parts of the country.”

Wernick believes that the four-decade history of the IBMA has proven to be a success story. “The IBMA has accomplished a tremendous amount of good things for bluegrass music,” said Wernick. “The organization is doing exactly what it was designed to do. I believe it has brought together the bluegrass community in many ways, which was very fragmented before 1985. In my opinion, there have been 20-year intervals in the bluegrass timeline that have been interesting to think about. The 20 years between 1945 and 1965 marked the distance between bluegrass’s beginning to the advent of bluegrass festivals. Then, twenty years after that, the IBMA was formed.”

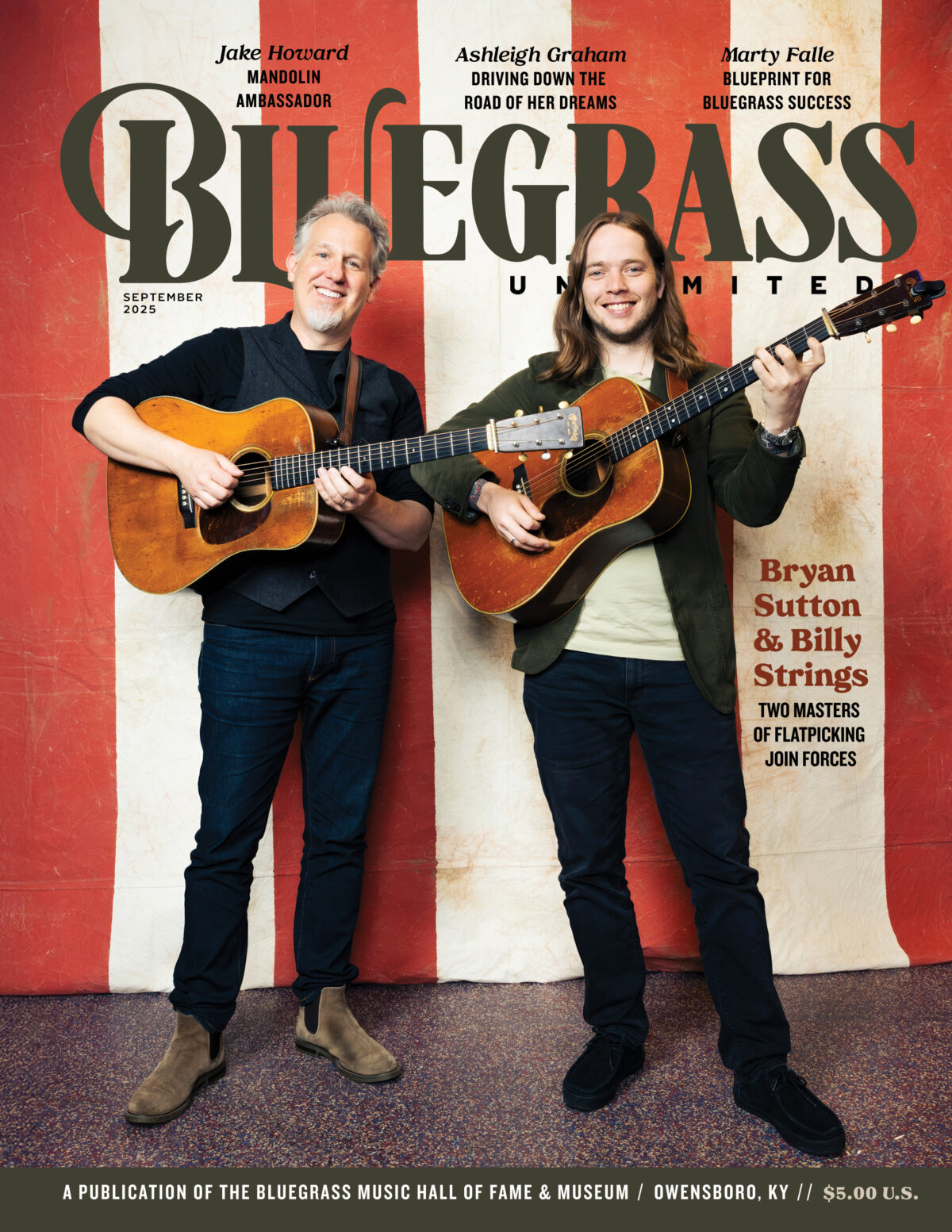

While not in an exact 20 year cycle, per se, the 8-million-selling music soundtrack album of the O Brother, Where Art Thou movie brought on a resurgence in the popularity of bluegrass and American roots music in the year 2000, and by 2019, Billy Strings won his first IBMA Guitar Player of the Year Award as his rise to international stardom continued.

“The IBMA Convention is still a good place to be if you are a band on the way up, so you can be noticed, and to meet other people that will be a part of your life for decades, from recording engineers and the DJs to the publicists and the social media people,” continues Wernick. “All of those people in different aspects of the business are now a part of a community that understands that it is a unique community and that we are there to help each other. Nobody fleshed that out as a vision at first, but everybody knew that was what we were working towards, as in to grow the bluegrass community and to prosper and to improve how bluegrass music is presented, without changing what bluegrass music is all about. There has never been a thing where the IBMA frowns on this version of bluegrass or that version, choosing X or Y when it comes to music, as it is an umbrella organization. Along with its predecessors, including the rise of the bluegrass festival and Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine, with both helping with the growth of bluegrass, the IBMA has made so many things possible.”

One of the best pieces of advice that Wernick received as President of the IBMA came from the late and great Hall of Fame musician John Hartford. “John would come up with a thought and then create a paragraph or a couple of sentences to describe his ideas, and then he would recite that paragraph in front of people,” said Wernick. “So, one of the things he would say is, ‘Don’t let bluegrass get too popular because then we’d have to share it with somebody that we fully don’t know. You know what happens when Walmart moves to town? Everybody has to start locking their doors.’ Those were pointed comments that he made to me as he didn’t want us to sweep a bunch of Nashville country music fans into our house without them really knowing what bluegrass music was all about.”

Dan Hays was the Executive Director of the IBMA for 21 years, ending his run at the helm in 2012. These days, Hays offers his leadership abilities to others as a consultant. Recently, he has spent a lot of time working with Marty Stuart on the latter’s new Congress of Country Music facility in Philadelphia, Mississippi, where they are restoring an old theater and turning it into a live music venue and a museum to showcase Stuart’s collection of music business treasures, photographs, and historical items.

According to Hays, it was Mac Wiseman who encouraged him to continue to go to Nashville and meet with the CMA Executive Director, Jo Walker-Meador. “She was very generous with her time,” said Hays. “We could sit down with her and ask, ‘Ok, how do you do this, how did this come about, and how do you make these things happen?’ She was very open to sharing that kind of information. Jo was tickled that we were there because she understood our journey. Jo actually started as a secretary at the CMA, if I remember right, and she grew into the job of Executive Director. When we walked in there, she said, ‘You know, we’ve never really known what to do with bluegrass music, so we’re happy that there are people and an organization out there that is working on its behalf.’ She loved our music and the people who played it.”

Hays was in his position as IBMA Executive Director when the O Brother, Where Art Thou soundtrack lightning strike hit the roots music world around 2000 or so. When the soundtrack of that film was released, featuring Alison Krauss and many others, it climbed in popularity and sales numbers and reached Number 1 on the Billboard Top 200 chart. For many people and many families, that album became the only recording with bluegrass artists on it in their music collection.

The soundtrack also won three Grammy Awards, including one for Album of the Year. Stunningly, the project also won the Album of the Year Award at both the CMA Awards and the Academy of Country Music Awards, which meant that bluegrass music had completely, albeit briefly, invaded the country music industry with aplomb.

“When they introduced the album to the people at the IBMA conference, people were just buzzing about it,” said Hays. “We were glad that a mainstream movie was highlighting the music, although the film Bonnie and Clyde did the same for us back in the late 1960s. But, even so, if you had told anybody that the O Brother soundtrack was going to sell eight million copies, they would have taken bets on that quickly. But, we were very happy that that album did rise up. It is much like today when we go, ‘Who is this Billy Strings guy selling out stadiums? What is that all about?”

Hays was also in his position at the IBMA when bluegrass became more prominent on the radio airwaves. “When it came to bluegrass shows on the radio, we had tried for years just to get a two-hour show on a college radio station in Poughkeepsie or an hour on a station in Sarasota and things like that,” said Hays. “Now, all of a sudden, they were sending up two satellites that were broadcasting Sirius Radio and XM Radio coast to coast, and both of them decided to have a bluegrass channel on their roster. The fact that both of them had a bluegrass channel to broadcast, even before they merged, was a godsend in terms of the accessibility and portability of bluegrass music sent out to the greater world.”

Nancy Cardwell began as the Special Projects Director at the IBMA in 1994 and eventually became the Interim Executive Director of the organization in 2012 when Hays stepped down. Currently, she is the Executive Director of the IBMA Foundation. “IBMA had the custom of adopting a new strategic plan every three years, and we called Fred Bartenstein out of retirement to serve as facilitator once more in 2013,” said Cardwell. “With limited resources, human and financial, a strategic plan was helpful during the entire time I served on the IBMA staff from 1994-2015, which enabled us to prioritize and focus our efforts. While ‘If you don’t know where you’re going, don’t be surprised if you don’t get there,’ is a poorly constructed sentence, it is actually true. The IBMA has always tried to plan ahead, while also being open to new ideas and developments.”

A part of the aforementioned future to come was the move of the World Of Bluegrass Week from Nashville to Raleigh, NC. “After the membership and attendance at the World of Bluegrass Week in Nashville had leveled off and lodging prices were going up at the conference, we turned the corner in 2012-14 thanks to the expertise of veteran staff member Jill Snider, with creativity and skills from new staff members Katherine Coe Forbes, Caroline Wright, and Taylor Coughlin Garner and a few others after that,” remembers Cardwell. “From March 2012 to April 2015, I managed a $1.4 million budget and nearly tripled financial assets in 2 ½ years, with membership found in all 50 states and 30 countries, as the membership increased overall by 40%.

“And, with a board of directors also interested in operations as policy making, we had a very successful first two years of World of Bluegrass in Raleigh in 2013-14,” continues Cardwell. “Also, thanks to the local tourism committee there, the city of Raleigh, a local organizing committee of volunteers, and great festival production provided by the PineCone organization, more than 150,000 people attended our World of Bluegrass Week in 2013. The local economic impact was $10 million, and we saw an increase to 180,000 people attending in 2014 with an impact of $10.8 million, and the sponsorship support for World of Bluegrass increased by 49% during this two-year period.”

Cardwell’s tenure also saw the beginning of a rapid increase in technology that would soon change the music business forever. “It was an exciting and challenging time,” said Cardwell. “There were some things I’d wanted to try, and having a talented young staff with digital design and IT skills helped us move forward. The IBMA didn’t tell folks in the industry how to embrace technology and run their businesses, but we did regularly feature guest speakers at our conference seminars, webinars, and as a part of the Leadership Bluegrass program that would address those issues while looking forward to emerging technologies and trends, all of which has pretty much come to pass.”

When Paul Schiminger became the Executive Director of the IBMA in 2015. He not only dealt with the onslaught of online streaming when it came to bluegrass airplay, but he also oversaw a fundamental change in how the IBMA organization worked. By the time he retired in 2023, some very important changes had been made to the IBMA charter that proved helpful in enabling the vision pushed forward by the late Sonny Osborne.

“Up until we decided to make a change, the IBMA was a 501(c)(6) organization for 30 years, and we then decided to change the IBMA into a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization,” said Schiminger. “As for the 501(c)(6) designation, that is a legal term for an organization being officially known as a ‘association,’ yet from my stand point, we at the IBMA were not lobbying politicians in Washington DC, which associations are allowed to do, and we were not negotiating contracts for our members. A 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, on the other hand, is a charitable organization that can support the arts and education more freely.”

Once that official change was made, the organization, and especially the IBMA Trust Fund, could be untethered from its earlier restrictions. “We were there at the IBMA to promote bluegrass music around the world and to facilitate education and connection throughout our community and to help artists advance their careers, and you can be a 501(c)(3) non-profit and do everything on that list,” said Schiminger. “Meanwhile, a 501(c)(6) association cannot accept tax-deductible donations or gifts, nor can it get grants from other foundations. We were leaving a lot of potential funding on the table that we could take advantage of, but after the change, we could focus our attention on the IBMA Trust Fund to make sure that funding was secure and prolific. Up until that point, virtually the only source of funding for the Trust Fund came from the World of Bluegrass Week profits. Now, we can not only get money for the IBMA organization from donors and grants, but we can also focus on donations from the public to raise money for the Trust Fund.”

That change truly made a difference when Hurricane Helene hit Western North Carolina, East Tennessee, and Southwest Virginia in September of 2024. While all of the help that comes from the Trust Fund is kept confidential, the impromptu benefit concert by dozens of bluegrass artists that happened on short notice at Donna Ulisse’s Wee Farm just days after the storm raised much-needed money, which greatly helped the many bluegrass musicians and their families that were impacted by that incredibly destructive storm. It was a beautiful and important night of fundraising with donations coming in from all over the country, and it would have made Sonny Osborne proud.

One person in the room on the night of the post-Hurricane Helene IBMA Trust Fund benefit show was current IBMA Executive Director Ken White.

While the World Of Bluegrass Week had a great decade-plus run in Raleigh, with the city truly opening up its venues and blocking off its streets for bluegrass music, White has overseen the upcoming move of the event to Chattanooga, Tennessee. “Raleigh has been a great home for our IBMA Week, but as for most organizations that have a conference, they move it around every year or two, so the fact that we stayed for 12 years in Raleigh is amazing,” said White. “The first time I went to Raleigh, I was blown away at how the locals embraced us there, and at how much hard work they all did to put those events on. When we decided to move the event, we met with a lot of people, and the folks in Chattanooga really impressed us with their hospitality as well as their willingness to step up and make it happen. Change is hard, but also, change is necessary.”

As Executive Director, White has had a very busy 2024 and 2025, yet he is 100% optimistic about where the IBMA and bluegrass music in general are going. “I have spent most of the last year just working on this transition to Chattanooga,” said White. “When you go to a new place, you have to make new relationships and you have to figure out new ways of doing things, and that has been all-consuming. I know that every time we have moved to a new city, there have been challenges. Sometimes, our audiences do not like change, yet once you get them there, they appreciate it. Now, they may be wondering, ‘Where am I going to stay? Where am I going to go? Where am I going to eat?’ But that will encourage folks to hopefully explore a little bit, and that will be a good thing, because there are a lot of great discoveries waiting for them in Chattanooga. So, the one thing on my bucket list right now is to make this transition to Chattanooga go smoothly.”

More information can be found at worldofbluegrass.org, www.bluegrasshall.org, and ibma.org.