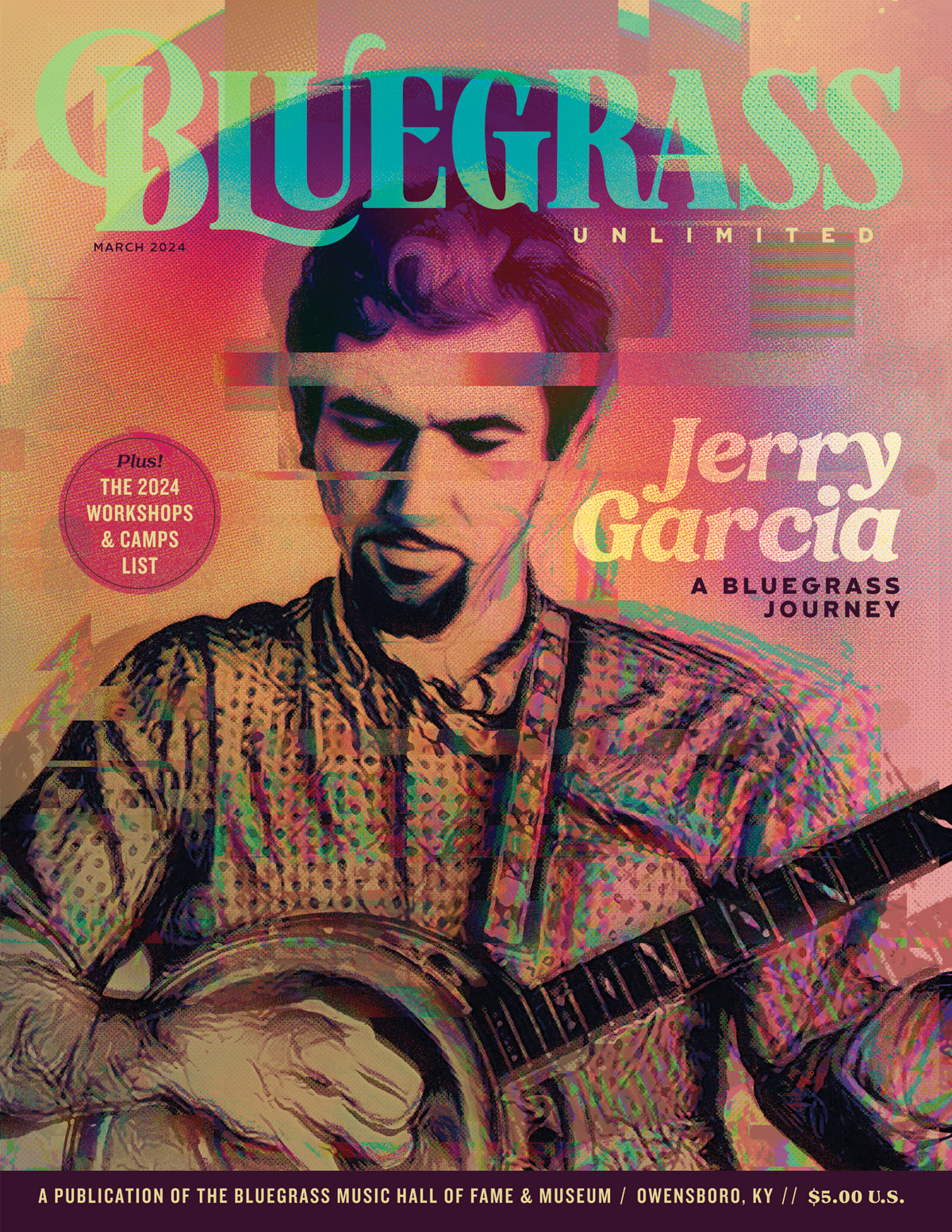

Home > Articles > The Artists > The High Lonesome Song of Jerry Garcia

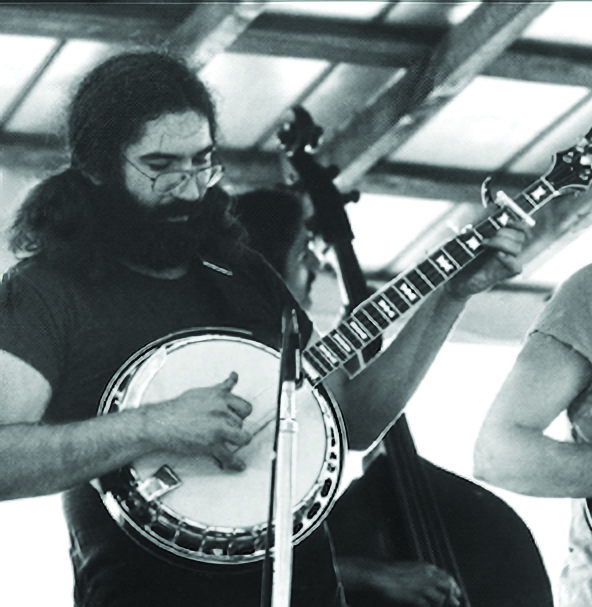

The High Lonesome Song of Jerry Garcia

Demigods don’t play the banjo. Scholars can point to a few lyre-playing immortals here and there in the pantheon, but that’s not picking the five-string, is it? And Earl Scruggs himself? Far too humble to make it in Valhalla.

Yet some say there was a Buddha-like figure from the West, an ageless spirit with an expanded mind who sang old ballads and played the immaculately conceived three-finger bluegrass banjo style. Here’s the thing though. Jerry Garcia never wanted to be sanctified or deified. He wanted people to be on the same level, to get along, and to share in the spirit of music. If anything, he was too successful at the latter, as the Grateful Dead became a phenomenon and a borderline cult for some. The Deadheads elevated “Jerry” to iconic and revered stature to the point where he could barely function. It troubled his equilibrium and quite possibly hastened his demise.

Amid the pressure of decades of adulation, Garcia would say sometimes that he most trusted the friendships he’d made before all the mayhem and the stardom, back when he was an unknown banjo player.

“When we were together in 1973,” remembers banjo playerand Hot Rize co-founderPete Wernick, “(Jerry) said, ‘You know, I consider people like you my real friends, because you knew me before the Dead.’” And it’s not like the two were intimates. But they’d played bluegrass together in the early 1960s, when that was the center of Garcia’s musical world, forming a bond for life.

Bluegrass, you see, wasn’t a byway in Garcia’s journey. Banjo wasn’t a diversion from his path toward rock and roll success. The genre and instrument laid the foundation for much of what came later and gave Garcia ideas about music that he’d weave into the Grateful Dead. In the documentary Long Strange Trip, Garcia holds up bluegrass as “a model for how a band could work” and nothing less than “a way to organize music.” He was impressed, as fans tend to be, by the push and pull in bluegrass between individual expression and group dynamics, between tradition and spontaneity. It’s not about finding parallels between Garcia’s banjo playing and his electric guitar, because he himself said the instruments were “apples and oranges,” but it’s about feeling the debt to bluegrass in the Dead’s innovations—their shared roots in the blues and a jazz-like ethos in which everybody’s interconnected, but everyone gets to express their unique voice.

“His roots as a bluegrass musician really helped formulate the concept that became the Grateful Dead and that rubbed off on everyone else in the band,” says award-winning Colorado guitar player and Garcia superfan Tyler Grant. “Those songs and the approach of how the instruments talk to one another, how the instruments communicate with one another in a bluegrass setting, really helped shape and define the approach the Grateful Dead took to their music.”

The “Startling” Banjo

Garcia’s parents named their second son for the great popular composer Jerome Kern and started his musical life with piano lessons, though Jerry never learned to read sheet music. His father, a retired jazz ensemble woodwind player who came from a singing Spanish family, drowned in a fishing accident when Jerry was five, leaving a void we can only imagine.

Coming of age in and around San Francisco in the 1950s and 1960s, Jerry was exposed to the big bang of rock and roll and the American folk revival all at the same time. When his mother bought him an accordion for his fifteenth birthday, he bridled and talked her into exchanging it for an electric guitar, but he admits he was pretty aimless about it. Then, after a short stint in the Army, where his resistance to authority was proven beyond a doubt, as well as a near fatal auto accident that helped him appreciate life itself, he got serious about music with a decisive turn toward folk and old-time.

Like so many others in the late 1950s, Jerry was seized by what he called the “startling” sound of Earl Scruggs and his five-string banjo. “I was attracted by the intensity of it, really,” Garcia told the Banjo Newsletter in 1991. “I think the first attraction is the incredible clarity and the sparkling brilliance of it. Then, as you play banjo, you start to be more conscious of the tone, of the inside—of the subtlety of it.”

Garcia taught himself, because one had to in those days, setting hard-to-find bluegrass LPs on half speed to work out Earl’s right hand rolls by ear and intuition. Jerry also adjusted to his unique digital disability, having lost his right middle finger in a childhood mishap with a hatchet, playing rolls with his thumb, first, and third fingers. And he became a leader, teaching guitar and banjo and showing the local musicians who desired to play bluegrass how the masters did it with their devious mix of drive, swing and blues.

Wernick, who at 17 lived for a summer with his family in Palo Alto in 1963, became part of Garcia’s picking community. He remembers how focused Jerry was on advancing as a picker. “The guys in Palo Alto went all the way down to L.A. to hear Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys when they came through. That’s a long trek. And then Jerry comes back. And he has heard Bill Keith, who had, at that time, a revolutionary style of playing the melodic style banjo. And Jerry went right about learning it. He had already learned a lot by the time I was around, and I was really impressed that he could pick that up.”

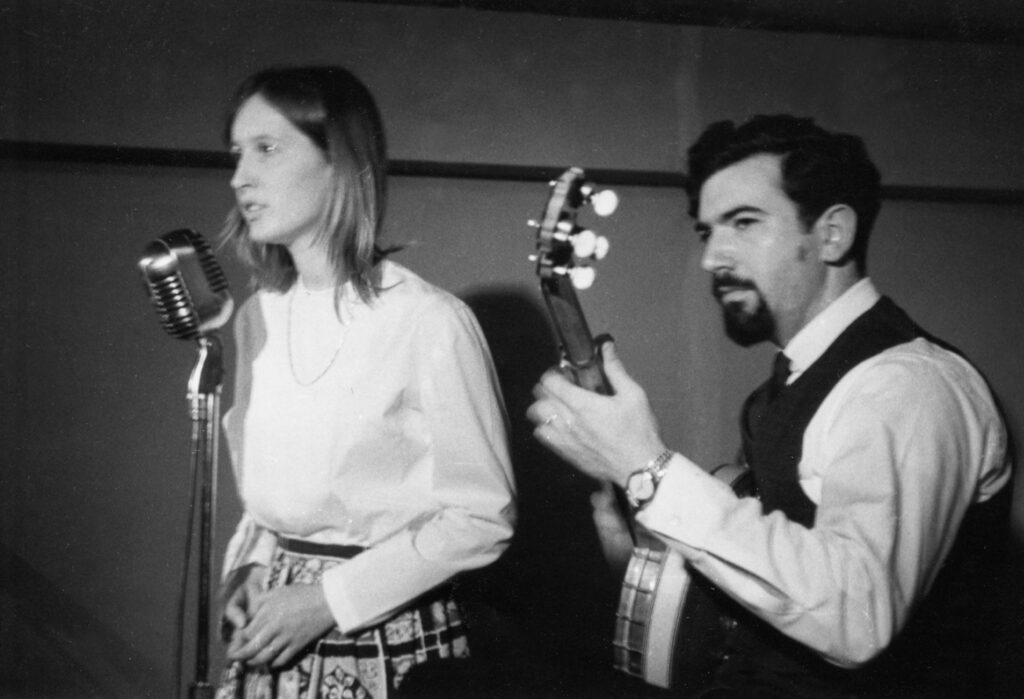

Garcia practiced so obsessively and often that it cost him his first serious girlfriend, but he made other relationships that would fundamentally shift his life—Robert Hunter who’d become his lifetime co-writer, David Nelson, his future partner in the country band New Riders of the Purple Sage, and multi-instrumentalist Sandy Rothman, a future Blue Grass Boy. With these and other proto hippies, Garcia started or got involved with a string of bands whose names sometimes belied their commitment to the music’s integrity—The Sleepy Hollow Hog Stompers, The Hart Valley Drifters, The Wildwood Boys, and most serious, the Black Mountain Boys. Here’s where Garcia first performed and recorded “Pig In A Pen,” sourced to Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith, standards like “Salt Creek” and “If I Lose,” as well as songs that would enter the Dead repertoire later, including “Dark Hollow” and “Rosa Lee McFaul.” Garcia played tricky Earl Scruggs instrumentals, including “Ground Speed” and “Flint Hill Special,” with its peg-twisting slurred notes.

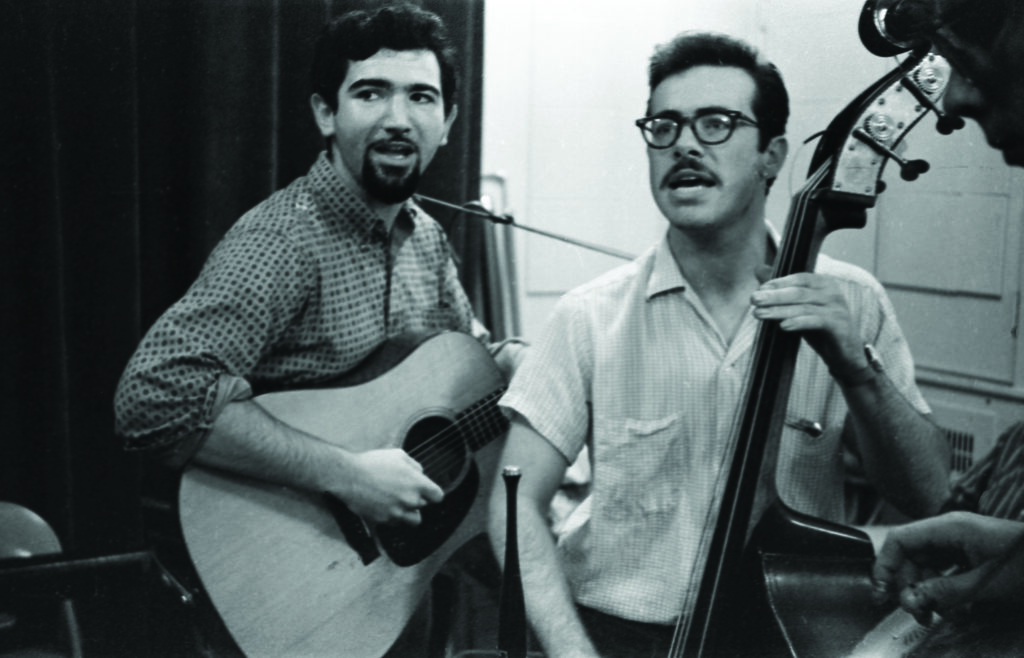

It was the time of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road, and Jerry Garcia decided he too needed an American musical pilgrimage. In the Spring of 1964, he and Rothman piled in Jerry’s white Corvair with instruments and a Wollensak reel-to-reel tape recorder and drove East, caravanning part of the way with California’s game-changing Kentucky Colonels. They caught Bill Monroe live in Bloomington, Indiana, and hung out with budding music historian Neil Rosenberg, future author of the seminal book Bluegrass: A History. They saw Reno and Smiley at a park near Columbus, Ohio, and Jim & Jesse play the Opry on regional television. But perhaps most fatefully, that trip led Garcia to Sunset Park in West Grove, Pennsylvania, where he met a young David Grisman, on his own journey deep into the music and playing with the upstart band the New York City Ramblers. “I had my banjo, he had his mandolin,” says Garcia in an Acoustic Guitar story from 2015. “We cranked a little bit and he kind of tested me. I guess he wanted to see if these guys from the West Coast could play.”

These were heady years of growth, but something profound and self-aware happened to Garcia after a few years playing old-time roots music. He felt himself thinking like a narrow-minded folk purist with strident opinions about how the music was supposed to sound and what was allowed. Yet his innate sense of rebellion seems to have kicked in. He recognized that he was becoming somebody he didn’t want to be and in the Long Strange Trip film, he says “I murdered that person.” In a flash, his muse became the electric guitar. His band became the Warlocks which quickly metamorphosed into the Grateful Dead. But the idea of “the instruments talking to each other” survived and became the heart of one of rock and roll’s most inventive and searching ensembles.

Old & In the Way

Acoustic roots music sat on the back burner for a few years as the Dead essentially invented psychedelic blues rock with a side of avant-garde sound-making. But the band’s folky heart resurfaced with two breakthrough albums in 1970—Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty. Grisman, by then a Bay Area resident, played session mandolin on the latter. The LPs remain classics of the country rock movement and they brought air and melody and imagery that would lure in new waves of admirers. The albums also seemed to suggest that Garcia might have more to say as a bluegrass artist, which came to pass in 1973 with his most influential side project.

Peter Rowan’s version has become the definitive story. In October of 1972 he moved to the Bay Area after his time as a Blue Grass Boy with Bill Monroe and his sharp left turn into cosmic rock with Grisman in the band Earth Opera. While hanging out, Grisman suggested they visit Garcia at his home above Stinson Beach. “Jerry Garcia?” asked Rowan. And off they went, arriving at a driveway with a sign above it reading Sans Souci, literally, without a care but which Rowan has memorably interpreted and intoned on stage over the years as “no problem.” And there was Garcia, picking the banjo and eager to play bluegrass with others again.

“Our rehearsals were hilarious and full of infectious spontaneity,” Rowan wrote for notes to the Old & In The Way Breakdown release. “Jerry was eager to play music at any hour. We tried songs from Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, Red Allen, Frank Wakefield, The Stanley Brothers and The Country Gentlemen.” They also worked up new Rowan songs “Panama Red,” “Land of the Navajo,” and the picking party staple “Midnight Moonlight.” Grisman conceived a title theme song to go with the band’s Garcia-inspired name. The repertoire and the attitude struck a seductive balance between the surprise-based music of the Dead and the rigor of Monroe’s music. Even if Jerry didn’t think he was playing all that well.

“I wasn’t nearly as good a banjo player in Old & In the Way as when I was 21, 22 and deeply into bluegrass,” he told Ken Hunt in a 1981 interview. “I had to practice for months just to get as good as I was when that band was happening, and even then it wasn’t satisfying to me because I knew what I’d been capable of. Even so, it had a nice feel, a flavor all of its own. And it was real fun for all of us for as long as it lasted. I really enjoyed it. I really did.”

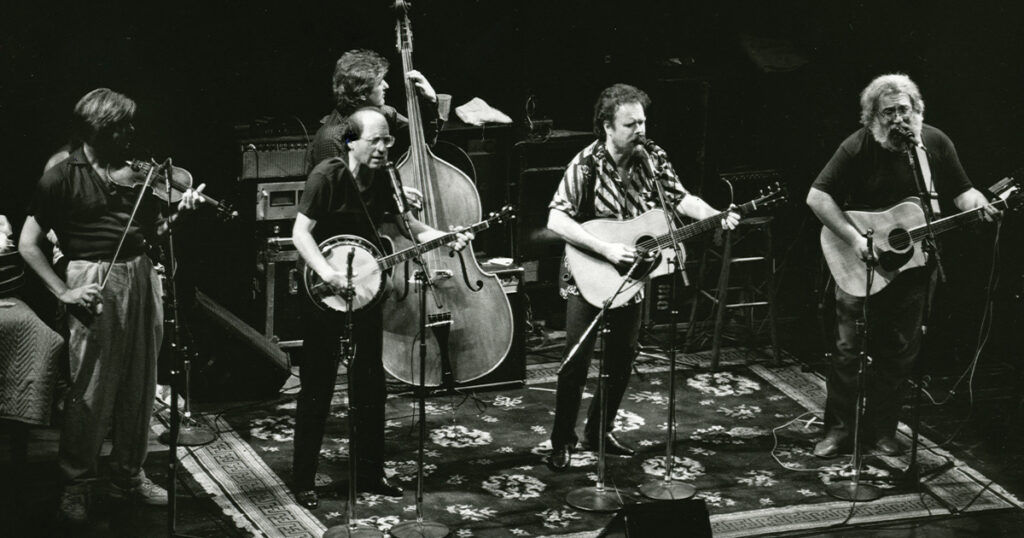

The band, rounded out by bass player John Kahn and the utterly unique Nashville fiddler (and former Blue Grass Boy) Vassar Clements, never went formally into a studio, but they played about 50 dates through 1973. Most of the shows were recorded, and two nights at San Francisco’s Boarding House in October 1973, recorded by the Dead’s sound man Owsley Stanley, became their calling card in the form of a ten-song eponymous album in early 1975.

Alas, by that time, the bluegrass band had dissolved, and Garcia had returned to the rigors and electrified power of Dead shows. But even in a prolific stretch of years that included the heyday of the Earl Scruggs Revue, New Grass Revival and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, this modest sampling of a good-time band of friends became the best-selling bluegrass album of its era and helped inspire the idea that one could be a fan of bluegrass and still hold a progressive outlook on music.

“Old & In the Way was a seminal recording,” says Tyler Grant. “In the sense that it was exposing bluegrass music to a whole group of people who hadn’t been exposed to it yet, and it has continued to do so in the same way the Grateful Dead’s popularity has perpetuated in this really unlikely and almost unbelievable way. And I personally was affected by that. It was a catalyst for me listening to bluegrass music more seriously. And then that became my life. And this is the story for so many bluegrass players.”

Reconnecting With Dawg

After Old & In the Way, Jerry Garcia stayed busy with the Dead, which enjoyed arguably its greatest artistic stretch in the mid-1970s and its most intense era of stardom in the later 1980s, as legions of new Gen X fans joined the caravans on the strength of 1987’s double platinum In The Dark. Jerry did indulge his love of country music playing pedal steel for his side project the New Riders of the Purple Sage between ’69 and ‘71. And while his bluegrass passion was largely in retreat, the Dead would sometimes break down into an acoustic format, as captured beautifully on the 1981 album Reckoning.

As a mid-1980s college student finding my way into folk and bluegrass, Reckoning’s renditions of “Dark Hollow,” “Rosalie McFall” and “Deep Elem Blues” transfixed me and pointed me toward a broad-based love of American roots music. The Dead’s yin-yang embrace of the acoustic and electric, the rooted and the fresh, struck my intuition as beautiful and meaningful. It set me up to appreciate Old & In the Way a bit later. Some of Garcia’s oldest mates, including Nelson and Rothman, got together in 1987-88 to record and tour as the Jerry Garcia Acoustic Band. And then in the 1990s came Garcia’s final act as an old-time folk and bluegrass artist.

David Grisman had spent the rest of the 1970s and 1980s developing and touring his unique blend of bluegrass, Latin and string band jazz that Garcia had indirectly dubbed “Dawg music,” though the old friends spent a dozen years out of touch. They’d had a small dispute over money, but Garcia mended the fence by sponsoring Grisman for an artist grant from the Dead’s foundation. Grisman was surprised by the check in the mail and called up Garcia to thank him and catch up.

“He said, we should get together,” Grisman recounted to me in a conversation last summer. “So I invited him over. He walked in the door and said, I know what we should do, we should make a record! And that’ll give us an excuse to get together. Wow, I said, I just started a record company.” (That would be Acoustic Disc, now with a remarkable catalog of music by Grisman’s many projects and other roots artists he admired.) Grisman had also just built a recording studio in his Mill Valley home’s basement, so he and Garcia had a place to play and track in peace.

“We walked downstairs,” said Grisman. “And I put two microphones up, and I still have the tape of what we played for the first time. Anyhow, it’s just been kind of serendipitous like that. And then we did over 40 sessions for the next five years until he passed away.”

Those sessions aren’t bluegrass per se, and Garcia plays acoustic guitar in almost all cases instead of the banjo. But the repertoire overlaps, and the body of work comprises some of the most elegant, sustaining and poignant recordings of Garcia’s career. Their seminal self-titled first release of 1991 included the traditional song “Walking Boss,” a tasty interpretation of Ted Hawkins’s “The Thrill is Gone,” the Civil War ballad “Two Soldiers,” and Grisman’s crafty instrumental “Grateful Dawg,” which toggles between sections that epitomize each artist’s instrumental voice and style. Subsequent releases, all produced and put out by Grisman, would include “Shady Grove,” “Nine Pound Hammer,” and “Sweet Sunny South,” with interpretations that many have learned and taken to heart.

“It really clicked,” Grisman told me. “I listen back to this stuff. I mean, almost every take is good. (Jerry) was really singing great. And I think we had developed. It was a point in our lives. We had similar backgrounds, not just musically. Both of our fathers were musicians (who) died when we were young. And we had a lot of common threads, you know? He’d think of a song, or I would, and we would just fall into this thing.”

By the 1990s, Garcia’s diabetes, addictions and heavy smoking had left him depleted. He’d been through interventions by his band and stints in rehab, not to mention a diabetic coma in the 1980s that nearly killed him. In the Gillian Grisman film Grateful Dawg however, we can see what a sanctuary Grisman’s home and musical collaborations had become for Garcia.

“Garcia encouraged Grisman to loosen up a little bit, and Grisman encouraged Garcia to tighten up a little bit,” says Grant of their musical dynamic. “And I think that’s attributed to their friendship and how well they knew each other. Because Garcia, being so sensitive and having such a struggle in his life, being under so much pressure and having these legions of fans who thought he was a deity, and then here’s just his old friend giving him some space. And I can’t imagine how sweet those interactions must have been between them.”

It wasn’t enough, sadly. Garcia died of a heart attack while in a rehab facility in California on August 9, 1995, launching yet another cycle of veneration. And of course Jerry is worthy of our love and respect. He was one of the most insightful innovators in American music and a seductive improviser with parallels to the spiritual sound fields of John Coltrane, the lyricism of Wes Montgomery, and the squalling freakouts of Frank Zappa. His songwriting, in tandem with Robert Hunter, added to the folk canon, as any picking party version of “Friend of the Devil” or “Ripple” will attest. He will forever gaze at us over his aviator glasses with a trouble-maker’s smile and an invitation to join the grand unifying song.

“I’m sure there’s a very substantial amount of bluegrass fans that came in through the Grateful Dead,” says superstar guitarist Billy Strings in one of the interviews conducted for the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s new special exhibit. “Which is such a cool thing to think—that this big psychedelic band was somehow funneling people down to Earl Scruggs, you know? But that just goes to prove that it’s true American music. The Grateful Dead, just like bluegrass.”