Home > Articles > The Archives > The Freight and Salvage Gives Bluegrass A Microphone On The West Coast

The Freight and Salvage Gives Bluegrass A Microphone On The West Coast

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1996, Volume 21, Number 4

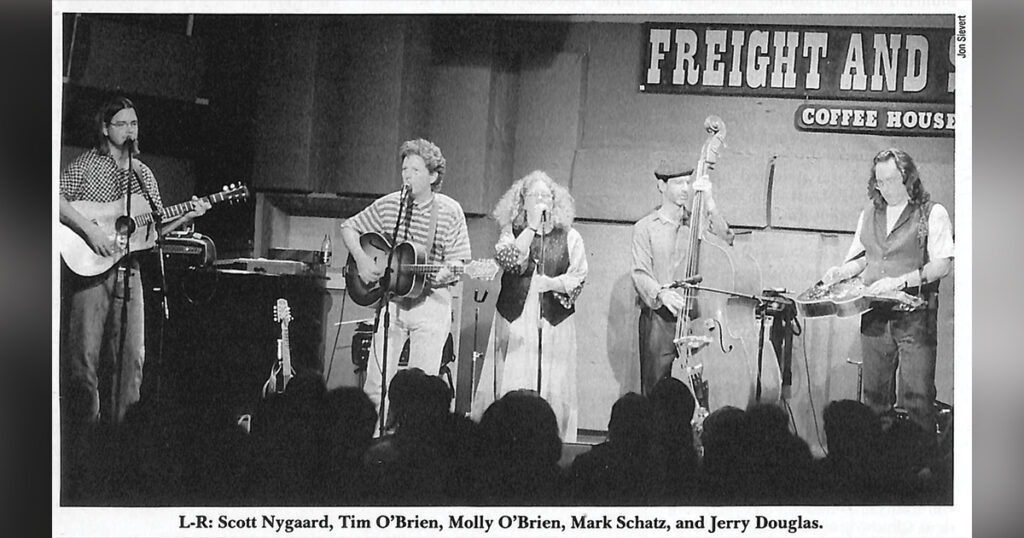

Tim O’Brien was just learning the fiddle in 1974 when he got the itch to go to California. He grabbed the instrument, slung a backpack over his shoulder, stuck out his thumb in Jackson Hole, Wyo., and hitchhiked to Berkeley.

While checking out the local music scene one night, he stumbled upon a benefit to save a funky hole-in-the-wall called the Freight and Salvage. The place was brimming with fans and musicians who had shown up to help: Shubb, Wilson and Shubb; Mike Seeger; High Country, and the Phantoms of the Opry. O’Brien, then 19, was knocked out by it all: the string band jazz from the Shubb trio and the gutsy singing from the Phantom’s Pat Enright.

“I really respected the fact that here were these hippie guys playing in the Phantoms and they were really traditional bluegrass,” he recalled.

Not knowing anybody, O’Brien hinted he wanted to play in the grand finale jam, but he wasn’t invited. It didn’t bother him much. He was eager to be part of the scene.

“Here was this little place—they couldn’t have been making very much money for The Freight—yet here were all these great players supporting it and making it possible to exist,” he noted.

Over the years, the coffeehouse has had to make some big adjustments, including switching to a non-profit corporation and moving into bigger quarters. But the strong sense of community has endured, enabling the Freight to thrive as the oldest acoustic music club on the West Coast. While other bluegrass venues have come and gone, the Freight offers bands a stable place to play and audiences a comfort able place to hear them, without the clang and clatter of a typical nightclub. The black brick walls reverberate with every variety of roots music, from downhome blues and singer- songwriters, to Celtic fiddlers and a cappella singers. Dana Carvey even appeared on the bill in 1979. The next year, a then-little-known singer named Shawn Colvin played at its “hoot night,” an important weekly open mike for the new talent.

“In my mind, the existence of the Freight and Salvage has been integral to the growth of West Coast bluegrass and you couldn’t write a history of West Coast bluegrass without including the Freight,” said Artistic Director Randy Pitts, who booked the acts from 1989 to the spring of 1996.

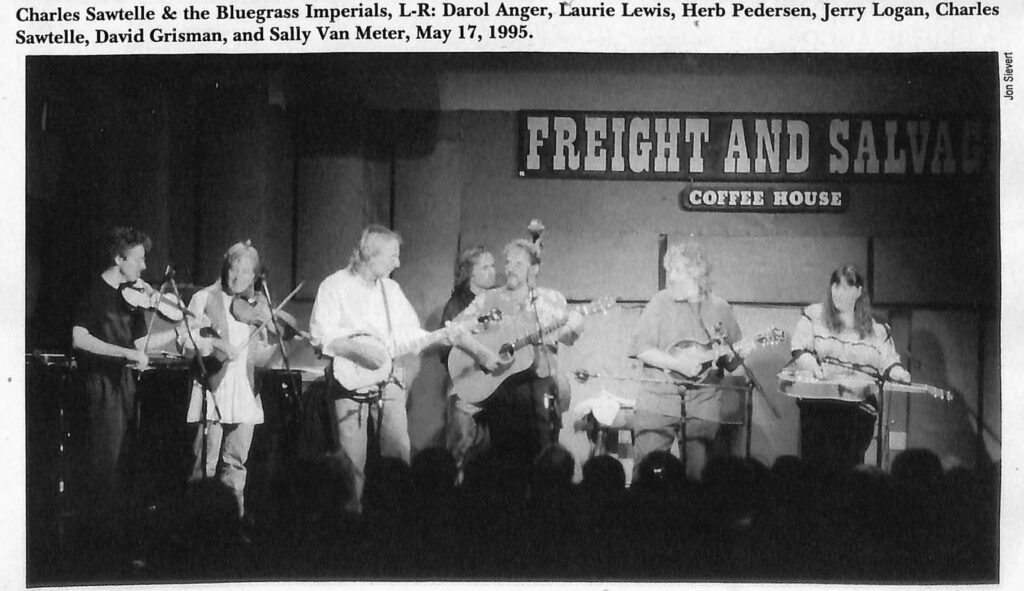

The old hand-drawn calendars from the ’60s and ’70s reveal a smorgasbord of monthly appearances by California greats, such as Vern Williams and Ray Park (Vern and Ray), Enright, Laurie Lewis and Grant Street, High Country, and the Good Ol’ Persons. Some of the West Coast’s most successful bluegrass emissaries cut their musical teeth on its stage, including banjoist Tony Furtado, resonator guitar wizards Sally Van Meter and Rob Ickes, fiddler Paul Shelasky, and Keith Little (an alumnus of the Country Gentlemen) and Ricky Skaggs.

Lewis said the Freight has been vital to her development as a singer, songwriter, and fiddler. She still plays there to sold-out houses. “It’s been like a home base for me to get my chops together and try out new material, but also the Freight and Salvage has had a real reputation as a listening club. You know people are listening. And when I first started playing the Freight, it was nerve-wracking for me. But having a place to play like that was vital to playing music for people who wanted to pay attention. If I only had pizza parlors to play in, I don’t think I would have developed as much a sense of nuance as I have.” Lewis said.

In November 1995, the Good Of Persons celebrated their 20th anniversary at the Freight, where they played one of their first gigs at a hoot night. “There has been a steady belief in the Good Ol’ Persons, even in the days of changing personnel and waning popularity. It’s been tried and true. That’s why the Good Ol’ Persons would not have their 20th anniversary in any place but the Freight,” Kallick said.

The club borrows its name from an old moving and storage company that operated in a small brick storefront on San Pablo Avenue. In 1968, a preschool teacher, Nancy Owens, rented the space as a folk music club and kept the name. The club changed hands several times and was eventually rescued from near demise by patrons and musicians who formed a non-profit corporation called the Berkeley Society for the Preservation of Traditional Music.

The Freight was small—holding only 87 people—but the acts loomed large from the wooden stage. Laurie Lewis fondly remembers sitting practically under the noses of Vern and Ray as they belted their spine-tingling duets. It was a treat for Bay Area audiences to have such authentic players to emulate so far afield from the music’s roots.

“They were loose. You never knew what was going to happen and who was going to be playing with them,” Lewis said. “They were wonderful. Those guys would come into Berkeley from the hills and play their butts off. It was raw. I heard Vern say one time, ‘To sing bluegrass you gotta spill your guts and walk in them.’ And that’s a very good description of what I heard them do at the Freight.”

The place was like a homey living room with mismatched chairs and a few tables. The backstage area was really a storeroom where musicians crammed in to warm up. Some even had moments of brilliance there, such as when Bryon Berline wrote “Huckleberry Hornpipe.”

“It was like a family situation, sort of like being in a big house together. The idea of some kind of status distinctions didn’t apply,” said Mayne Smith, a founder and former board president for many years. “People really believed in it and participated in what was going on there.”

Supporters rallied again in 1988 when the Freight was forced to move because of tripling rent. Through a series of musical benefits and donation drives, the society pulled off a stressful and expensive move into a theater a block away, fighting opposition from the adjoining residential area.

The new Freight, located at 1111 Addison St., Berkeley, is much roomier, holding up to 240 patrons. The sound system is a great improvement and musicians have access to a bigger dressing room. But the biggest advantage, said Pitts, is that the newer place has been able to bring in acts that it couldn’t afford before.

The expansion of the Freight has also presented challenges. Drawing a substantial audience for a newer band without name recognition is often tough in a hall more than double the capacity of the old one.

“Five years ago, I think a traveling bluegrass band, any touring band, you could count on certain hard-core blue- grass people to be at the event and that’s no longer the case,” Pitts said.

Despite the challenges, the Freight continues to serve a steady diet of blue- grass, being true to its mission to give a voice to all varieties of music.

The non-profit organization traditionally shares most of the money it makes at the door with its musicians. And the players return in droves to say thanks in numerous benefits.

It’s this image that has stayed with O’Brien as he returns to the Freight regularly, these days as the star of the show.

“It’s the community that revolves around it,” he said. “It’s the fact that’s been the place to see and hear this kind of music for so long. People are really loyal.”

Chris Lewis is a newspaper reporter living in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is also the mandolin player for the bluegrass band the All Girl Boys.