Home > Articles > The Archives > The Fiddling of Sam Bush

The Fiddling of Sam Bush

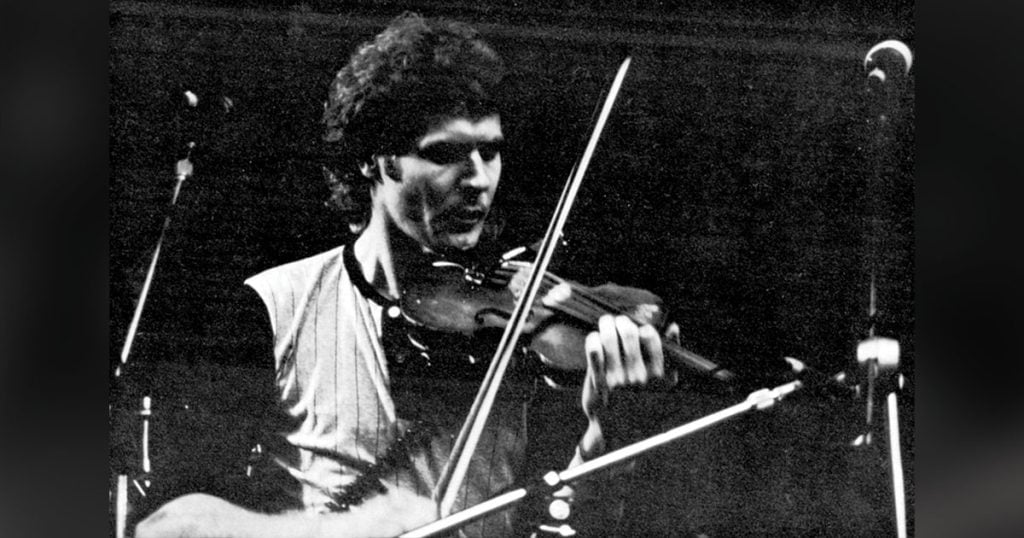

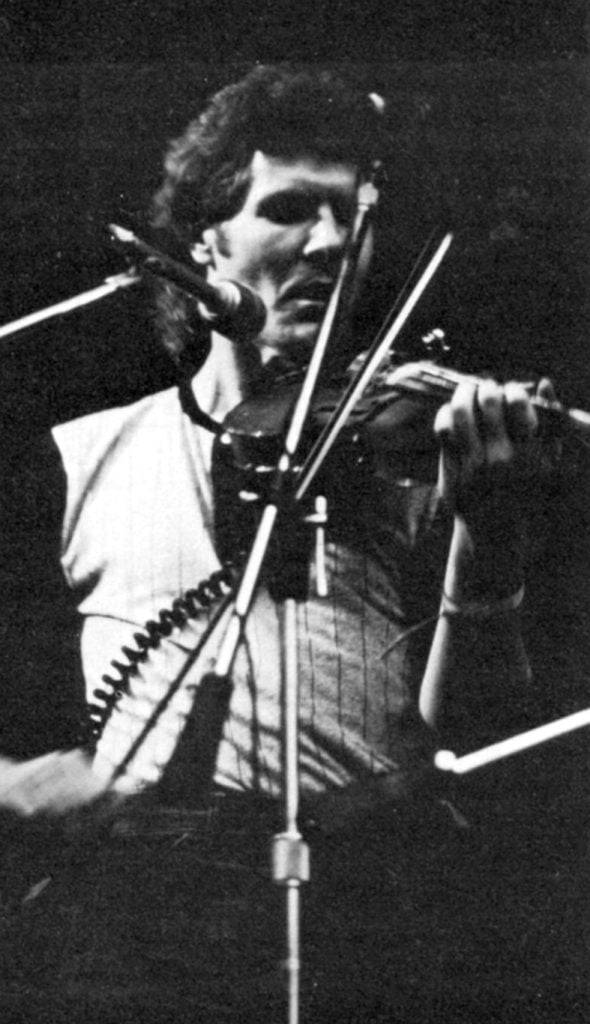

Photos by Ron Evers

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1985, Volume 19, Number 8

If I could re-live one musical experience it would be listening to Sam Bush’s fiddle jam on that newgrass tour de force, “Don’t Look Back,” performed August, 1982 outdoors at Green Acres Music Hall, near Rutherford, North Carolina.

Despite the sweltering heat, that mesmerizing delivery had it all: form, feeling, visual appeal, and above all, intensity. A dark gyrating figure in front of a deep red stage backdrop, Bush drew me into the vortex of his musical exploration with the sheer power of a wizard in total control of his craft.

It is not surprising that various writers have described his fiddling as “surreal,” “flamboyant,” “dynamic,” “varied.” It’s all of that, and much, much more than can be heard by listening to recordings. It literally has to be seen and heard to be comprehended totally with all of the physical, mental, spiritual and mystical implications.

And yet, despite the effect his fiddling has on audiences, Bush maintains an almost deprecatory modesty about it, delighting in and preferring, at times, to praise the fiddling of others. His list of favorites reads like a Who’s Who of Fiddling, Past and Present.

“There’s just loads,” he says. “You can name ’em all day. I tell you one of my favorite fiddlers in the world: Tex Logan. Tex plays the most far out things I’ve heard, just about by anybody. He plays a lot of stuff in seventh position! It just fries me! He plays it in seventh position before he plays the open strings!”

Bush’s capacity for being amazed at the fiddling of others is surpassed only by his capacity for spontaneity in his own fiddling. And, perhaps, by his ability to amaze and astonish his audience. Just when one thinks, for example, that there’s no coming back in his ethereal “Don’t Look Back” jam, he switches suddenly into a high-geared rendition of that classic Bill Monroe tune, “Scotland.” Terra firma is still nearby: just hold on to your seat and we’ll be landing soon.

Besides being a brilliant salute to Monroe and bluegrass, that digression into a more musically conservative genre underscores Bush’s roots as a traditional- style fiddler. And one who can take an old tune and treat it like it just drifted in through the cosmic gates. “When I learned to play,” he explains, “it was in square dancing style. That may be part of the strength right there, that I’ve always beat out the rhythm as I play. I think part of the strength lies in the rhythm.”

He beat out the rhythm with enough finesse to win three Junior National fiddle Championships before he graduated from high school. He never went back to Weiser for the adult contest because, “I was too busy playing for a living as an adult.” He has, however, placed as high as third in the Grand Master’s Fiddle Contest held annually in Nashville.

Two strong influences on Bush’s early fiddling were Tommy Jackson and Byron Berline.

“My dad got me started on fiddling when I was 13,” he says, “and I actually learned a lot of stuff from listening to records. I learned a lot of stuff from a fiddler in Kentucky, Lonnie Peerce. The first person I ever tried to copy was Tommy Jackson. To me, Tommy Jackson’s albums were the greatest inspiration to learn from, especially the square dance tunes.

“I was first exposed to Texas fiddling when the Dillards came out with ‘Picking and Fiddling’ with Byron Berline. When I first laid the needle on that record and Byron started with ‘Wagoner’ it blew me away. I had never heard anything like that, and from that point on I was just engrossed in the Texas style.

“I have tremendous respect for Byron. Whenever he touches the fiddle, it always sounds good to me. I’ve never heard Byron play something that I thought didn’t sound good. That’s an extra-ordinary gift.”

Although engrossed in Berline’s fiddling and the Texas style, Bush’s fiddling began a steady process of diversification which has culminated in its current eclecticism, incorporating elements of old-time, blues, jazz, rock, Irish, classical, and even Indian forms.

His unfailing sense of rhythm is evident in a powerful bowing style which he attributes in part to the classical violin training he had from violin teacher Betty Pease while he was still in high school.

“She was amazing, and she had a lot of respect for people who didn’t necessarily play classical,” Bush says. “After it was all said and done, I decided I enjoyed playing the fiddle style better.

“When I play the fiddle I just enjoy doing things. I try to do things that haven’t necessarily been done in the style of music that I play, because I have also been influenced by jazz. Not jazz violinists so much as jazz-rock violinists. Jean-Luc Ponty was a big influence.”

Bush’s joy at “just doing things” is an emotion that he conveys convincingly to his audiences. Sometimes, when the fiddle jam is going particularly well, a mischievously boyish grin erupts on his face. At other times his face seems illuminated by a kind of ecstacy that is religious in its intensity. Regardless of the expression, the atmosphere around him at such times becomes rarified, the sound supercharged, the dynamics palpable. Uncharted worlds are being mapped out for us to follow. Unsurprisingly, it is not being planned that way at all.

“When we do a long jam tune, the kind of thing where I play a solo without restrictions, then I’m pretty much an automatic pilot,” Bush says. “I am discovering something. When the communication is up in the room between the band and the bodies, I can feel it. I think when things are going best for me musically, I’m not aware of plotting out each note. It’s just falling out of me.

“Without getting too cosmic, it really is just coming through you. I don’t know if any musician ever really thinks up the notes. Sometimes I believe you can tap into an incredible source that a lot of other people tap into. And that’s why you communicate without words. You have a musical conversation with the audience.”

Although Bush prefers the mandolin, which he took up before the fiddle, he admits that “since I plugged the fiddle in I enjoy it a lot more. One of the main reasons is because I don’t have to play so hard and I don’t have to fight the rest of the group to be heard when I’m using a pick-up.

“In recent years I’ve gotten so that I enjoy the fiddle almost as much as the mandolin. I still feel more competent on the mandolin, especially in the studio.”

His modesty belies the fact that he has played fiddle on record with such acoustic giants as Doc Watson and Tony Rice, not to mention his early records with Alan Munde and some impressive fiddle work on the New Grass Revival albums. The two early albums set standards for traditional-style fiddling that have been matched by few other fiddlers.

He says that one of his favorite fiddle recordings “was also one of the simplest things I ever did, and also one of the hardest tunes I ever played. It was ‘Pear Tree’ with Doc Watson. I just always liked to hear that back.

“I played a couple of things with Oswald and Charlie that I like, and also ‘Manzanita’ by Tony Rice. Also, on ‘Acoustics’ by Tony Rice I was real satisfied with a few things I played. A lot of times I hear my fiddling back and it doesn’t sound as in tune to me as it did at the time.”

Bush says he also liked the New Grass Revival recording of “Lee Highway Blues,” but that “I’m looking for a new way to do it. We do get requests for it, and I don’t want to stop doing a tune that people want to hear. But at the same time, I’m looking for new things.”

Of his own original classic, “Old Widow Woman” (on the “Sam and Alan —Together Again” album) he says, “I was trying to write a tune that was a new tune that someone could mistake for an old one. The best tunes for me just come out of my head.” (One apparent exception is ‘Foster’s Reel,’ on the same album, which Bush describes as an unusual tune for which he actually scored out the notes as an exercise in high school —“At the time it was fun,” he says. “Now [he laughs] it’s not such fun, but then again that was a tune that just came out of my head.’’)

Although he is not a prolific composer of fiddle tunes, the ones he writes are memorable, difficult technically, and some, like the relatively recent (and as yet unrecorded) “Indian Hills,” draw on exotic sources.

“That tune touches upon Indian scales, but doesn’t play in any Indian scales,” Bush says, “because I’m not that knowledgeable about Indian music.”

Bush confesses a preference for fiddles with a deep, resonant, low-ended sound, which is well-suited to the tunes he has composed and to the deep rich musical sensibility he displays in both his compositions and his interpretations. “Norman Blake told me, ‘Boy you really like them old gourdy fiddles!’” Bush says with a chuckle. “I guess I do.”

“The fiddle I’m playing now is a copy Stradivarius that Courtney Johnson found in a junk shop in New Mexico in pieces for $40. Courtney’s got an amazing way with instruments. He put it back together and stuck a little red varnish on it—actually it’s more of a red stain—and boy I heard that thing and I asked him if he’d trade one for another.”

Bush’s current hero on the fiddle is Mark O’Connor. “The only thing wrong with his playing is that he never makes a mistake,” he says with a laugh. “I just don’t think I’ve ever met anybody that’s so gifted and has such a beautiful touch on the fiddle. Mark has the control over it I wish I could have.”

But Bush is aware of the danger of calling anyone “best” on the fiddle. “As a fiddler you can’t ever close your mind, or you can’t ever think that you’re the greatest because just when you think you are, somebody’s gonna come along and show you you’re not. And even if you were, who cares?

“My violin teacher, Betty Pease, respected all people who play. Maybe I learned it from her. Just respect people who play, no matter what their style.”

How does Bush compare the fiddle to the mandolin as a means of tapping the musical source?

“I can’t speak as one instrument over another,” he answers slowly, “because when I’m truly tapped to the source I’m not really thinking about anything. As far as whether the fiddle can reach out to more people or not, it’s hard to say. At one time for me country music was fiddle music. It changed in the ’50s and bluegrass also changed from the old-time string bands, so it’s hard to say.

“All I know is that the fiddle always does seem to communicate with people when we use it sort of as our ace in the hole and we play a country show or something. Once we pull out the fiddle, it sort of comes into its own.”

Bush says that a lot of people have talked about his recording a fiddle album, but that “I haven’t really thought about it that much. I’ve never just sat down and thought, well I should make a mandolin album or I should make a fiddle album. It’s the same way that I’ve gotten in trouble all through my musical career. I just want to make a big musical statement, and not necessarily any one kind of music…”