Home > Articles > The Archives > The Elusive Prewar Flathead

The Elusive Prewar Flathead

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1989, Volume 23, Number 11

Everyone chooses favorites and of all the Gibson banjos termed ‘prewar,’ the wreath pattern RB-3 with flat tone ring stands out as my all-time choice. There is a quality combining the delicate mother-of-pearl inlays, serviceable mahogany wood and nickel-plating, that is significant considering the economic level many of the bluegrass banjo pioneers found themselves in during the early years of the music.

Grenadas are great, no question about it and the tasteful combination of beautiful curly maple, dark stain, celluloid bindings and mother-of-pearl made it a classic long before Earl, Sonny, J.D. (for a time) and others added their mark of distinction to the flathead versions.

I’ve seen and cut out a lot of hearts-and-flowers and flying eagle pearl patterns, so can’t be accused of abnormal bias during the thirty or more years since we started converting tenors to five-strings to help correct the numerical imbalance between the two types and customer needs and preferences dictated working with virtually all models during this same period of time.

The wreath patterns were made earlier and fancier in both ballbearing and solid and forty-hole arch tops such as the TB-5 and in fact, was the most expensive model Gibson offered in their early catalogs, before the tenor player market brought about such carved, engraved, gold-plated extravagant models as the Florentine, Bella Voce and All American.

My personal inspiration dates back to the Rudy Lyle-owned wreath RB-3 banjo which my brother traded for and then traded to me. It may go a step further back to the first time I saw Bill Monroe and the gleam of the plating and pearl on stage left a subconscious impression, at the same time Rudy was giving an inspired musical performance as only one can when the Father of Bluegrass is overseeing the proceedings.

For all the history that banjo had been part of (played on classic Monroe recordings of “Rawhide,” “White House Blues,” etc), the rim had been damaged and the neck and resonator poorly refinished. The tone ring was changed over to a solid wood rim and the neck and resonator used in several temporary situations, but at this late date, nothing is known about the location of any of the original parts.

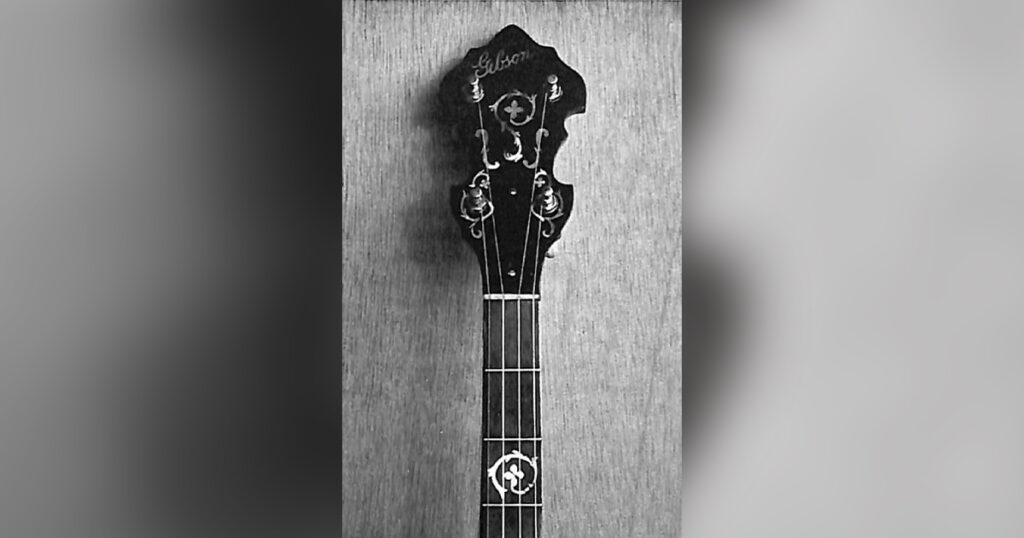

The five-string wreath flathead is something of an anomaly, as they occurred after the TB-5 had disappeared from Gibson’s advertisements and to my knowledge, were never pictured in any catalog. They had the same artistically pleasing pearl design as had appeared earlier in a fiddle-shaped peghead, but were not inlayed in the double-cut shape used in the 1930s when they were built.

Another departure from the norm is that the Mastertone block was inlaid into the fifteenth fret space (the only model like this), and it is almost as if the craftsmen were bored with the style of the plainer mahogany Mastertone of the time and decided to build a few ‘high-powered’ RB-3s, just for diversion.

In the late 1950s, I was able to trade for an original RB-3 (like the catalog version), but it took a brand new RB-250 to separate it from its owner and by this time the banjo had been sent back to Gibson to be refinished and a new ‘bow-tie’ fingerboard installed. It also had a ‘no-holes’ flat ring originally, that its subsequent owner, Paul Champion chose to modify.

By the time an album cover appeared showing the unmistakeable earmarks of another original five-string, my sources of information divulged that one Joe Drumright, residing somewhere in the Nashville area, was indeed the owner of a wreath RB-3. Further inquiry revealed that Joe had known Rudy Lyle and they had compared notes (literally), but sometime later Joe traded and defected to the archtop camp.

The plot thickens as we move the scene, appropriately, to North Carolina and one enterprising individual who found two wreath flatheads, one a plectrum model and the other an elusive five-string original. For reasons known only to him (or her), the necks were exchanged. Marc Pruett bought the original pot for the five-string, it was then sold to Bob Ginn, but the next owner was from a location so culturally-and geographicaly distant as Sweden!

I’ve always been amazed (and sympathetic) when folks in other countries have heard something in our music from such a great distance that causes them to want to learn to play or own the instruments classically associated with bluegrass music. First, at least one-third of the appeal is seeing a band play, so they have overcome a large obstacle in turning on to the music in spite of a missing element when learning from records only.

Also, the hazards of buying an instrument from such a great distance are legion, if the tone doesn’t meet ones expectations, unscrupulous individuals misrepresenting the item and little recourse to have such instruments authenticated or the hassle of returning for a refund. We’ve dealth with and had visits from folks from Japan, Australia, Switzerland, England, France, New Zealand and, Sweden and are always struck by the extra effort these people go to to learn more about the music we sometimes take for granted.

An excellent example is Ake Tydeh, the Swede who bought the original flathead pot, but took curiosity to some unusual extremes. He has an unusual feel and appreciation for tone, whether it be in Scruggs style banjo, Tommy Jackson fiddle, or a Martin guitar. Ake took several additional steps with the banjo toward fulfilling an as yet unrealized dream to have the alloy and dimensions reproduced by carefully measuring the original tone ring.

Also, though the reproduction neck he owned played well enough, Tyden was haunted by the nagging knowledge that somewhere in the United States there was still existent the original five-string neck that Gibson had built for the banjo. It is a real credit that from such a great distance, with more than a little detective work to trace down the part and by paying a premium price, this outstanding student of bluegrass instrument history was able to reassemble this very unusual banjo.

Ake was also able to determine that a pearl nut and fifth string pin (like found on the Grenada) would indeed change the tone of his original and the scale length was longer than the 26 and 1/4 inches used by modern builders. The Tyden story, however, does not end happily there. A combination of personal items (not the least of which was peer pressure in Sweden question the banjo’s authenticity) caused him to sell the instrument back in this country and it is likely it will stay here for many years to come.

When Ake read in Bluegrass Unlimited, that Curly Seckler and Earl Scruggs would do a reunion show in Ohio in 1988, he took the opportunity, albeit costly, to learn first-hand the standard of excellence for bluegrass banjo tone.

Also, when he left Kennedy International Airport for the return flight to Sweden, carefully disassembled and packed in separate items of his luggage were a TB-7 pot, tenor neck and excellent reproduction five-string neck that will go a long way toward replacing the collector’s item he sold!

The credit has been given to a foreigner for service above and beyond the call of duty to reassemble another example that just as easily could have been lost forever.

Imitation being the sincerest form of flattery, it is easy to see that others share my reverence for this inlay pattern, due to the large number of copies, both domestic and imported, being played today.

It still leaves some basic questions unanswered. Were there only such a small number of original five-string wreath flatheads built, ever? Is there a logical explanation that a discontinued pearl pattern reappeared several years later, in a less extravagant model?

Given the intrinsic simplicity and beauty of this banjo and the chance that very few—possibly as low as less than five only were made, is the 1930s Wreath pattern flathead possibly the most rare and collectible of all the elusive Gibson prewar flathead five- strings?