Home > Articles > The Archives > The Delmore Brothers—On The Opry

The Delmore Brothers—On The Opry

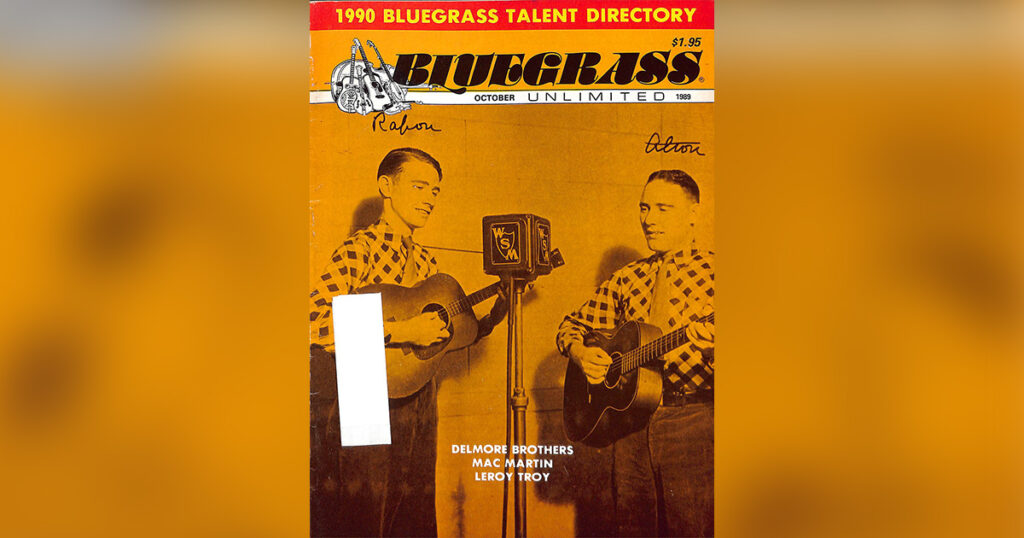

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1989, Volume 24, Number 4

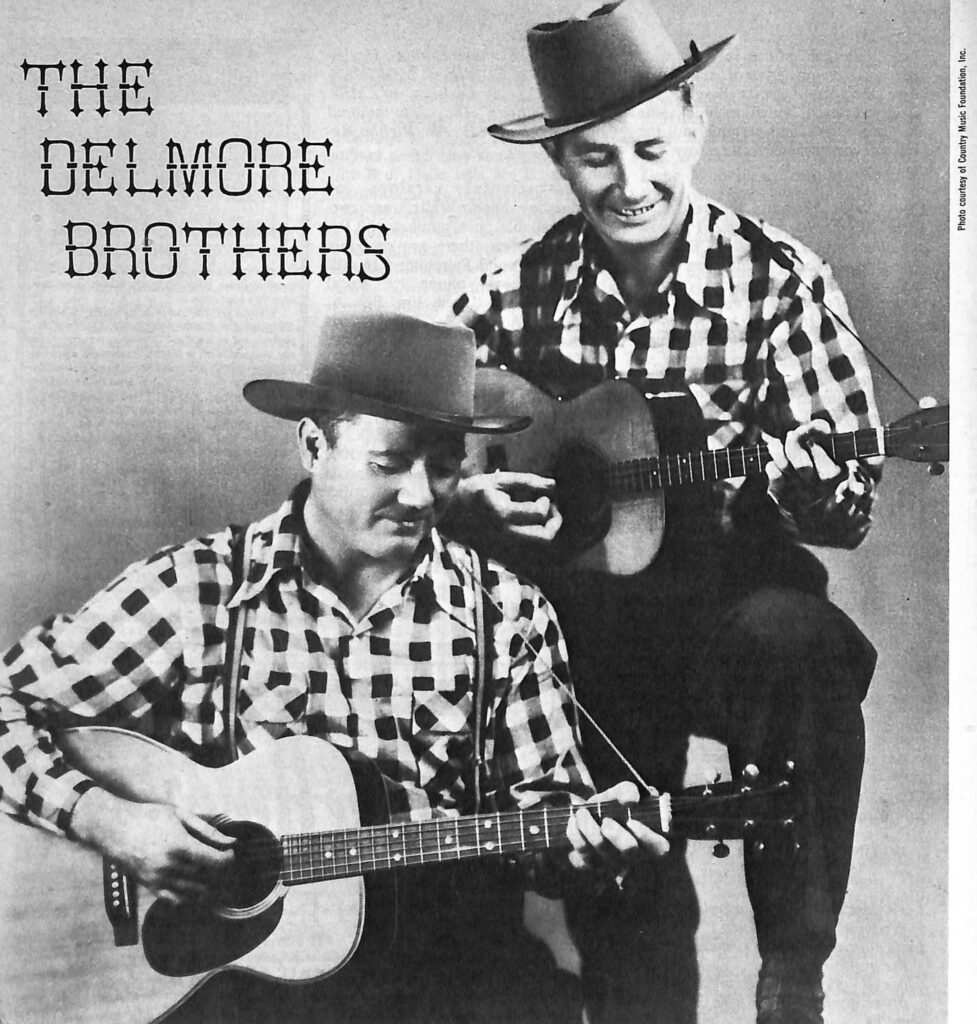

Without a doubt, the most popular group on the Opry in the mid-1930s was the group that became perhaps the most famous singing duo in country music history, the Delmore Brothers. They joined the show in the spring of 1933. To the casual fan, the Delmores (Alton and Rabon) might be seen as just another duet act from the 1930s, when the music suddenly blossomed with popular acts like the Callahan Brothers, the Monroe Brothers, the Shelton Brothers and the Bolick Brothers (the Blue Sky Boys). But the Delmores were far more than just another duet act; they were one of the very first of these acts and they retained their popularity longer than many of the others. They generally sang original songs and they sang them in a close-harmony style that influenced generations of country performers. Though they were certainly a transitional group on the Opry, they were in fact one of the most vital transition groups in country music history; they linked the blues, ragtime and shape-note singing of the rural 19th century South with the polished, complex, media-oriented styles of the 1930s and 1940s.

The Delmores were transitional in another sense, too, for they were among the first country acts to appeal to a wider audience. As we have seen, any fully professional act on the Opry in the early 1930s—that is, any act trying to make a living at their music—had to appeal to a wider audience than the barn dance audience; they had to be able to hold down weekday shows on WSM in order to get enough of a salary to exist. The Delmores learned to do this well and to even transmit this appeal to records; some of their records, like “Beautiful Brown Eyes” and “More Pretty Girls Than One” (both recorded with Arthur Smith), were among the earliest “crossover” hits in the music, selling both to rural and urban audiences. Like the Sizemores and the Vagabonds, the Delmores were literate and sophisticated, but unlike them the Delmores had a genuine folk base for their music. The Delmores not only had style, but content—not a content derived from 19th century sentimental songs or popular “heart” songs, but from the rich traditions of northern Alabama. This content was filtered through the creative imagination of one of the music’s finest composers, Alton Delmore.

Though much of the Delmores’ success came from their own innate skill and drive, part of it came from their being in the right place at the right time. Jazz critic Whitney Balliet has written of the importance of the development of the hand mike in changing the style of American pop singers; it moved them away from the loud booming style of the acoustic era to the subtle nuances of the Crosbys and Sinatras. A similar argument could be advanced for the development of country singing. In the 1920s it was necessary for the Carter Family or Riley Puckett to generate enough volume to allow them to be heard under rather primitive staging conditions. But by the 1930s radio had made it possible to sing softly and still be heard and by the mid-1930s sound systems had developed to the point where in-person concerts could accomplish the same end. The first generation of country stars—Rodgers, the Carters, the Skillet Lickers, Uncle Dave Macon—could not entirely depend upon radio to establish their reputations; their artistic style was not really suited to the new radio medium. But the second generation of country stars sensed the absolute need to fit their art to the medium and the Delmores were among the first of this generation. With radio their carefully crafted harmonies could be appreciated and their effective lyrics be understood.

Both brothers were born in Elkmont, in north Alabama—Alton on Christmas Day, 1908, and Rabon on December 3, 1916. Their parents were tenant farmers who struggled to eke out a living in the rocky red clay of north Alabama and the brothers saw hard times for much of their early lives. But musical talent ran in the family: the boys’ mother and uncle were both skilled gospel singers who could read and write music. Their Uncle Will (W.A. Williams) was a well-known area music teacher who had composed and published several hymns and gospel tunes. Often the entire Delmore family would sing at revival meetings and “all day singings” held at tiny churches throughout the South. Alton’s mother taught him to read the old shape-note music and he learned even more by attending the various singing schools held in rural churches. In fact, by 1926, when Alton was eighteen, he had published his first efforts at songwriting in one of the paperbacked shaped-note gospel songbooks common in the area. This one was called Bright Melodies and it included two songs with composer credits to Alton Delmore (music) and “Mrs. C.E. Delmore” (words); Mrs. C.E. Delmore was Alton’s mother. The songs, however, were listed as “property of Alton Delmore,” which suggests his mother’s contribution might have been token. Whatever the case, neither song is especially different from the eighty or so others in the book; one is called “We’ll Praise Our Lord,” and the other is “The Vision Of Home, Sweet Home” (“Jesus who loves me, my pilot will be/As I’m crossing death’s rolling foam”). The book was published by a local firm, the Athens Music Company, which had been started in the early 1920s by songwriter and teacher C.A. Brock, whose son Dwight would go on to become one of gospel music’s best-known pianists. The effect on Alton of having an important shape-note publishing company located in his back yard is hard to underestimate. Throughout his life he would continue to publish gospel songs in these small paperbacked books issued by publishers like Winsett throughout the South and would eventually help form one of the most famous of gospel quartets, the Brown’s Ferry Four, in the early 1940s.

By the time Rabon was ten (about 1926) the brothers were playing together and singing the close harmony duets they later became famous for. They sang informally in the community and at local fiddling contests. Alton recalled later that a major influence on their singing had been the amateur gospel quartets that flourished (and still flourish) in the rural South. Rabon was also learning to play the fiddle at this time and Alton often backed him on guitar. The brothers began to repeatedly win first place in the singing divisions of the Limestone County area fiddling contests and local newspapers began to praise them in print. Alton, who was working at this time as a printer and a cotton gin hand, recalled: “We never tried to sing loudly. We couldn’t have if we had wanted to because we both had soft voices.” Their first successful appearance was at a fiddler’s contest on the Elk River in western Limestone County. Alton recalled: “It came time for Rabon and me to play and some of the fine bands had already been on the stage and made a big hit with the crowd . . . The only thing was we could not play as loud as the others had played … We picked out two of our best ones. I think the first one was “That’s Why I’m Jealous Of You.” We sang it a lot in those days and it was a good duet song. When we first began to sing the crowd was kind of noisy but we hadn’t got through the song before there was a quietness everywhere. You could have almost heard a pin drop. Then we knew we had a good chance at the prize, even if there were only two of us. When we finished there was a deafening roar of applause. If the crowd had not quieted down there probably would never have been an act called the Delmore Brothers.”

Encouraged by this success, Alton began writing radio stations and record companies asking for a try-out; he got firm but polite refusals. Then the Delmores met up with the Allen Brothers, a successful duet from nearby Chattanooga who had recorded a string of records for Victor and Columbia, including a lot of “mountain blues” material like “Salty Dog.” The Allens were sympathetic to Alton’s plight, and suggested that he began stressing his original material in their auditions. They did this and in 1931 landed an audition with Columbia records.

Thus the brothers traveled to Atlanta in 1931 to record their first records. Throughout the 1920s Columbia had dominated the old-time record market with their famed 15000 series, but the depression was hitting the record business hard by 1931 and the end of the splendid series was soon to come. The Delmores’ single recording, “Alabama Lullaby” and “Got The Kansas City Blues” (Columbia 15724), was one of the last in the series and sold a mere 500 copies. The promised contract was not forthcoming and in fact Columbia itself was to virtually be out of the record business (temporarily) in a couple of years. But the trip had other valuable benefits. At Atlanta the brothers met several of the great artists from Columbia’s “golden age,” including Riley Puckett, Clayton McMichen, Fiddlin’ John Carson and Blind Andy Jenkins. (Carson, of course, had recorded the first country record back in 1923 and Jenkins composed hundreds of early country ballads, including “Floyd Collins.”) These greats of a passing age all praised the Delmores’ singing. Alton recalls that John Carson told the other musicians in the studio, “Now if you want to hear some real singing just shut up and listen to these two boys and then I’ll bet you’ll be glad you did.” Then John and Andy Jenkins asked them to play “a song or two” just for them. “What would you like us to play,” Alton asked. “Oh, just anything you boys want to sing and we’ll help you,” replied John. Alton recalled: “I was dubious about the last part of his statement but we fired into ‘Left My Gal In The Mountains’ and before we were halfway through all those record stars were over there with us, singing along just like a choir. It was, and still remains, one of my biggest thrills of all time in show business.”

Alton then began writing to Harry Stone, the manager of Nashville’s WSM. That station’s Saturday night “Barn Dance,” which had been rechristened the “Grand Ole Opry” only four years earlier, was quickly gaining popularity throughout the South. Alton recalled later: “We all knew that the Grand Ole Opry was the greatest show on the air at the time. Or at least people in the South thought so and we were Southerners.” But for a year Stone wrote back offering little encouragement. The brothers hung on. “We were still playing school houses and any other place we could book and still the old fiddlers’ contests and we brought home some money nearly every time—precious money that kept some food on the table, along with daddy’s help. We were treated almost as celebrities in our home Limestone County, Alabama, but we didn’t have the money to make the thing real.”

Finally, in the spring of 1933, the boys received a letter from Harry Stone asking them to come up for an audition. Though Stone didn’t say so, the Pickard Family was leaving WSM to go to Chicago and he had a slot to fill on the show—preferably a slot for a singing act. The audition got off to a bad start: it was set up for Monday and the brothers dragged in on Tuesday, angering Stone, who had plans to take in the opening game of the Southern League baseball schedule that day. The brothers then made another faux pas by singing a version of “When It’s Lamplighting Time In The Valley” with the Vagabonds present in the room; they walked out when they heard the Delmore version, mainly because they were so sick of it. But then Stone asked how many original songs they had and seemed happy to hear that they had around 25; he then asked them to play some sample “request” songs—standards and current favorites that listeners expected, like “Silver Haired Daddy Of Mine.” Stone then left, and the Delmores, assuming they had failed, started down the stairs of the National Life Building. Only then did Stone appear over the top railing and shout down that they had a job on the Opry. They made their debut on the show on April 29, 1933, in a regular fifteen-minute segment following that of DeFord Bailey.

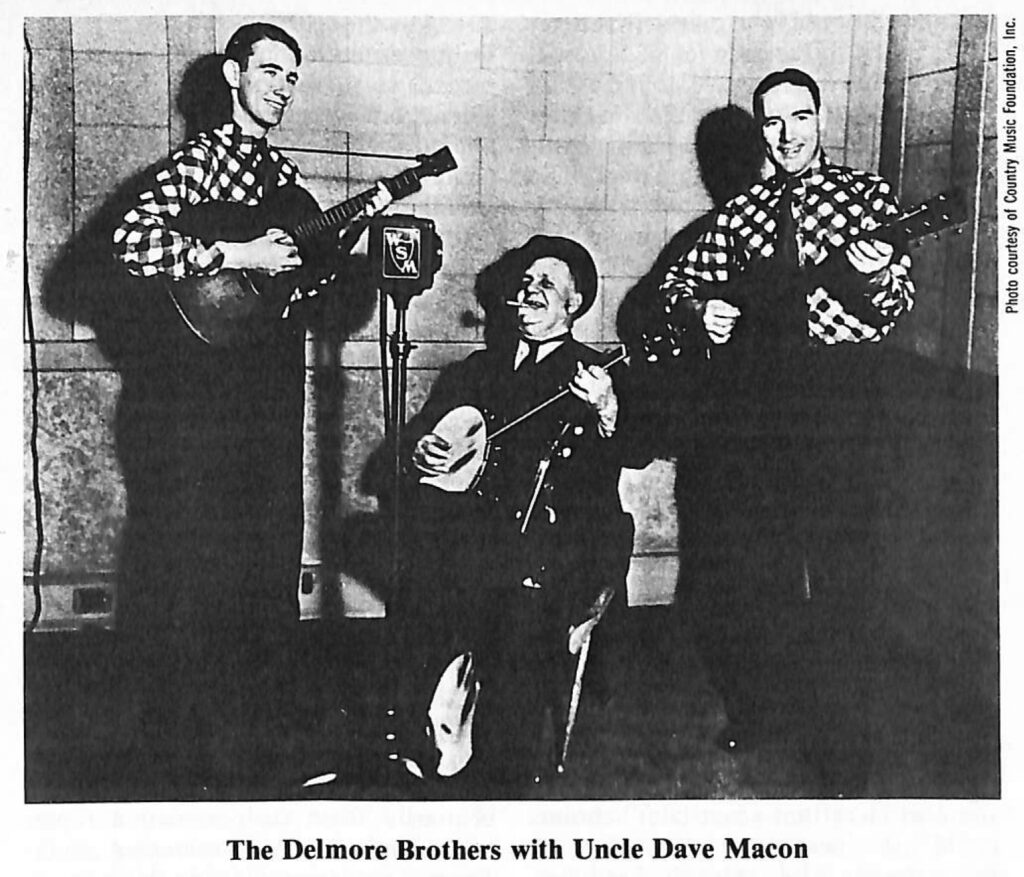

The Delmores’ stay on the Opry was stormy and controversial at times, but it gave them the exposure and national audience they needed. They became popular at once and soon were receiving more fan mail than anybody else on the show except Uncle Dave Macon. They read much of their mail—it was as yet a novel experience for them to get fan mail—and made up lists of numbers that were requested and Alton even typed many personal letters in reply. They had an unusual rapport with their audience, but were disappointed at not being able to get any tour bookings. (To the early Opry artists, personal appearances were necessary to supplement the meager wages paid by the station.) In December, 1933, the brothers journeyed to Chicago to make their first Bluebird records for Victor; they drove up with another popular singing group from the Opry, the Vagabonds.

Eli Oberstein, who did so much of Victor’s hillbilly and blues field recording in the 1930s, was in charge of the session. The seventeen sides from this session included two of the brothers’ most enduring numbers, “Brown’s Ferry Blues” and “Gonna Lay Down My Old Guitar.” (Alton had composed the former as a contest song; when they had almost been bested by a group singing “comic” songs, Alton decided that if the public wanted comic songs, he would give them one. He named the song for an old ferry site near the Delmore home on the Tennessee River. The brothers had been playing on WSM for a year before station manager Harry Stone heard them doing the number in a jam session and insisted they include it on their radio programs.) The Delmores soon became the most successful recording group on the Opry.

Yet during their early days on the show, the brothers were at times struggling to make ends meet. Like the Vagabonds and the Sizemores, they had to have weekday appearances on WSM in order to gain a living wage. But unlike the Vagabonds and Sizemores, they had not come to the station as seasoned entertainers. Alton described their plight this way: “There were two classes of entertainers at WSM. The staff members, the ones that got paid every week and knew they had a good job and security, and the other class, the Grand Ole Opry talent, who played only once a week and were paid a very token fee for each Saturday night. Rabon and me found ourselves in the middle of the group. We didn’t get a good salary but we played three times a week on the morning shows and sometimes on other programs they had when they needed someone like us.” The Delmores tried to solve this problem at first by going out and seeking bookings on their own. Uncle Dave Macon, noting that by 1935 the Delmores were getting more mail than anyone else on the show (except for him), asked the pair to tour with him in a tried-and-true circuit of school-houses and small-town meeting halls. Uncle Dave had set up by now an impressive network of school teachers, Chamber of Commerce officers, lodge leaders and small town mayors that had known him since before the days of radio. Alton wrote, “If he wanted to play a week in a certain part of the country, all he had to do was write someone a letter and they would book him and he always made good money.” This method, of course, by passed the newly created WSM Artist Service Bureau, with its 15% commission, but since Macon was an old, established star, with established ways, little was said. Alton and Rabon worked well with Uncle Dave—they even got to where they sang trios with the older man on hits like “Over The Mountain”—and for a couple of years became regular touring partners with him. “Everybody was happy and we began to make some pretty good money right at the beginning,” recalled Alton.

By 1936, though, this arrangement was causing trouble. Judge Hay had by now taken over the Artist Service Bureau and was trying to set up tour packages that would pair the hottest new acts with some of the older groups whose popularity had waned, or with some of the newcomers who had not yet proven themselves. The Delmores were hot and Hay saw no need for them to be paired with his other biggest star, Macon. For a time, therefore, he paired them with Arthur Smith—until Smith himself, on the strength of his Bluebird records and hits like “More Pretty Girls Than One,” emerged as a star in his own right. “We used Arthur on several appearances and got a real good little show started,” wrote Alton, “and then they took him and put him with another act and wouldn’t let us use him anymore.” The Delmores, always anxious to “professionalize” their work found themselves on occasion paired with veteran Opry acts who still tended to look on music-making as hard-drinking, informal fun. When Alton complained to them about too much drinking, or their not taking show dates seriously, one of them told him, “By God, I was playing on the Grand Ole Opry when you and your brother were just plain cotton pickers and I ain’t gonna let no goddam cotton picker tell me what to do.” The touring problem became an increasing point of friction between the Delmores and the Opry management. Alton at one time tried to work out a separate contract with the Sudekum theater circuit ($70 a day for the two of them), but Hay learned of it and stepped in to insist that the Sudekum take on an entire Opry package tour—one which quickly folded.

By the middle of 1937, though, the Delmores were being singled out in WSM press releases as the most successful performers on the Opry. One release says: “Young farmers, these boys, aged 28 and 23, have beat out some ‘new’ folk songs which have given them instantaneous popularity with followers of the Grand Ole Opry.” Much is made of the Delmores’ recording career: “In every nook and corner of the land, one can hear recordings of the Delmore Brothers being played—in corner drug stores, at church festivals, in private homes, wherever the charm of the folk-tunes, or hillbilly songs penetrates.” During their stay on the Opry, in fact, the Delmores managed to record some 80 sides for RCA’s Bluebird label—and for the Montgomery Ward mail-order label (where they enjoyed their own separate listing in the Ward’s catalogue). Their best-seller was “Brown’s Ferry Blues,” which by mid-1937 had racked up sales of more than 100,000 copies—an astounding figure for a Depression-wracked economy. Their average record sale, according to the WSM press release, was 35,000 and their yearly earnings from recording and copyright royalties average around $4,000; ASCAP benefited the Delmores [with performance royalties for their compositions] as well as the Berlins and Gershwins, the release concludes. “Brown’s Ferry Blues,” “Southern Moon,” “When It’s Time For The Whippoorwill To Sing” and “Gonna Lay Down My Old Guitar,” the biggest Delmore originals to date, were already being “covered” by dozens of other radio and recording artists. WSM also gave the Macon-Delmores trio credit for introducing 1936s top hit “Maple On The Hill,” as well as 1937s biggest radio hit, “What Would You Give In Exchange For Your Soul”— even though the Delmores did not follow these up with recordings (though Uncle Dave had recorded the former back in 1927). The relationship between radio popularity and recorded hits was still unsettled, even as late as 1937.

The exact ways in which the Delmores formed a new synthesis from older components of southern music can be seen by examining their very first Bluebird session. This seventeen song session, held in Chicago in the winter of the worst year of the Depression, has to rank as one of the most auspicious debuts in country music history (discounting the 1930 Columbia try-out). It produced four recordings that were to become standards; “Gonna Lay Down My Old Guitar,” “Brown’s Ferry Blues,” “Blue Railroad Train” and “The Frozen Girl.” It also produced several songs that would become Delmore favorites over the years: “Lonesome Yodel Blues,” “Big River Blues,” “The Girls Don’t Worry My Mind” and “I’m Leaving You.” (Yet another song that became a standard, “When It’s Time For The Whippoorwill To Sing,” was brought to the session by the Delmores, but they got into a wrangle with the Vagabonds over the publishing rights and the Vagabonds wound up recording the song instead of the Delmores. Things were so confused that Alton and Rabon did not record the song until 1940, when they moved to Decca records and for a time in 1933 the Vagabonds were publishing a version of the song in their folio with composer credits to Goodman, Upson and Poulton. “It took me two or three years to get it all straightened out,” wrote Alton.)

One type of synthesis was to take the “blue yodel” and falsetto singing that had been popularized by Jimmie Rodgers a few years before and add to it a high, intricate harmony. Such a harmony yodel impressed Oberstein, the Victor A & R man, for he chose as the first Delmore Bluebird releases two numbers that featured it: “Lonesome Yodel Blues” and “Gonna Lay Down My Old Guitar.” Alton’s autobiography is silent as to where the brothers got this technique, but it had been recorded as early as February 1932 by a team of west Tennessee singers named Reece Fleming and Respers Townsend; their harmony yodel, though, a stiff, hooting sound, cannot compare with the graceful, pliable style of the Delmores. The Delmore harmony yodel became an important staple of their stylistic arsenal and they used it with increasing dexterity as the years wore on, eventually creating with it masterpieces such as “Hey, Hey, I’m Memphis Bound” (1935). And the Victor A & R men came to think so highly of it that they went out of their way to note on the session ledgers which songs had yodels and which did not.

Another Delmore innovation was their use of close harmonies and a “soft,” almost intimate, manner of delivery. Country duet singing before the Delmores emerged in 1933 had been casual and slapdash, as with Darby and Tarlton or Riley Puckett-Hugh Cross, or stiffly formal, as with the gospel-trained efforts of Lester McFarland and Robert Gardner. Much of it used “open” harmony, where the tenor used a note higher than the nearest natural harmony, much in the manner of modern bluegrass harmony; the Delmores, however, drew upon their formal musical training, with it harmonics and sense of pitch, to create a style using a very close harmony. Most of the time it was Alton who sang lead to Rabon’s harmony, but if the range of the song dictated it, the brothers could switch back and forth—even in the same song. The close harmony was unique and influential on a generation of duet singers, including the Blue Sky Boys, the Crowder Brothers, the Callahan Brothers, the Girls of the Golden West and others. The harmonies also worked, as we have seen, because people could hear them with the new radio microphones and public address systems. Alton himself sensed this watershed between the first and second generations of country musicians when he described the Delmores’ first live public appearance, at an old-time fiddling contest in Alabama where there were no microphones.

A third aspect of the Delmore fusion of old and new was their superb guitar work, which survives today in music as diverse as that of Chet Atkins and Doc Watson. Many of the “turnarounds”—the instrumental passages between vocal verses—on the very first Delmore session were done on a little tenor guitar, played on occasion by Alton and on occasion by Rabon. Alton taught Rabon how to play the instrument: “I had brought it home with me from Decatur. I taught him the first chords on it and I played it like a tenor banjo. So that’s the way he learned to play it.” The Delmores were probably not the first country act to use a tenor guitar—for a time, the Vagabonds even included one in their act—but they were certainly the first to use it as a lead instrument and the first to do breaks with it. In addition, Alton himself was a formidable flattop style guitarist who once amazed the legendary Georgia guitarist Riley Puckett by outplaying him on his own specialty, “A Rag.” Though some fans have compared Alton’s playing to east coast bluesman Blind Boy Fuller, Alton himself acknowledged other masters: in his late teens he spent some time convalescing from an illness. “I started listening to the various recording artists, Jimmie Rodgers, Carson Robison, Nick Lucas, Riley Puckett and Eddie Lang. These are the fellows I copied mostly. I would take a little from the style of the first one and then the other till I had my own style. And besides playing some of their runs and riffs I emphasized the melody and would play the song like anyone would play it on the piano or the violin or any other lead instrument and that is where my style was different.” Alton’s mention of Nick Lucas is intriguing, since Lucas also published an influential series of instruction books and on occasion spotlighted the tenor guitar. Throughout the 1930s, the Delmores would remain the only duet act to feature the tenor guitar (as opposed to the mandolin or second guitar) and it helped give them their unique sound.

Finally, there are the Delmore songs themselves—perhaps the most important examples of their fusing of older musics to create something new and distinctive. Their second record issued from the Bluebird session was Bluebird 5538, “The Frozen Girl” backed with “Bury Me Out On The Prairie.” Both are songs steeped in tradition. The former, with its haunting “No home. No home” first line, is more commonly known as “The Orphan Girl” and had been collected by folklorists and even recorded (by Buell Kazee and McFarland and Gardner) before the Delmores did it; in a later King re-make of the song, Alton would announce that it was “over 100 years old.” Yet much evidence suggests the song was usually sung as a solo in earlier days; the Delmores brought it to their harmony and a surprisingly fast waltz tempo on the guitars. Yet it worked. It was a hit for Bluebird and remained a favorite in the Delmore repertoire. “Bury Me Out On The Prairie,” under variant titles like “I’ve Got No Use For The Women” and “The Gambler’s Ballad,” had also been collected by folklorists prior to the Delmore recording, and had even been recorded several times by early country groups in the late 1920s. The Delmores probably got it from the Vagabonds, who included it in their 1932 songbook. To it they brought, again, their harmony, a brisk tempo and sparkling tenor guitar breaks. Throughout their career, the Delmores would continue to revamp old folk songs, albeit sparingly and only when the songs fit their style.

The real centerpiece of the Delmore repertoire—and the secret weapon that gave them the advantage over lesser groups like the Vagabonds—was the body of original songs created by Alton. Based on older lyric patterns and rhetoric of blues, gospel and 19th century Tin Pan Alley chesnuts, they nonetheless seemed fresh and new because of Alton’s synthesizing abilities. Two examples appear on the Delmores’ third Bluebird release, Bb5358, “I’m Leaving You” and “I’m Going Back To Alabama.” The former is based on a classic blues stanza pattern in which the first line (in this case, “I’m leaving you this lonesome song”) is repeated three times before the completing line (“Cause I’ll be gone, long gone, some day ’fore long”). This in itself is not so unusual—Jimmie Rodgers did a lot of this—but the Delmores add to this a call and response echo on the first three lines, much in the manner of a gospel quartet. The mixture works and Alton was to repeat the formula on later songs like “Fifteen Miles From Birmingham.” “I’m Going Back To Alabama” is derived from the South-as-nostalgia mode that city singers like Carson Robison and Vernon Dalhart exploited so well in the 1920s; after rambling around a bit, it’s always great to go back home. This theme, too, was to be a Delmore staple, but with an important difference: Alton’s keen eye for detail. Whereas Robison sang of a vague “Blue Ridge Mountain Home,” the Delmores singled out specific southern locales: states like Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Mississippi, cities like Memphis, Birmingham, Nashville. Others sang of “prison” in a vague generic sense; Alton sang of the “Alcatraz Island Blues.” This trait too he might have borrowed from country blues singers, whose songs were always full of specific geographic details— some so clear that years later scholars could use clues in the songs to track them down. Also, Alton’s keen perception of the southern landscape afforded him specific images and honest references; night-birds cry, in “I’m Going Back To Alabama” and the moon in summer is so bright that you can use it to roam around. Alton genuinely loved the southern landscape and continued to use it in songs year after year. Finally, Alton and Rabon peopled this landscape with real people—not Victorian maidens and earnest suitors. They sensed that while the form and style of the older songs was appealing, they would have to graft onto it a more modern view of love. Thus “Lonesome Yodel” features the refrain “You’re gonna be sorry for what you done,” while “I’m Leaving You” start off, “I’m leaving you this lonesome song.” Images of separation abound, as do references to isolation, hurt and anger: “There’s no one to cry for me” (“Old Guitar”), or “If I sink just let me die” (“Big River Blues”). At other times a bitter misogyny surfaces; “I’ve got no use for the women,” they sing in one place (“Bury Me Out On The Prairie”) and “I don’t let the girls worry my mind” they sing in another. A generation before honky-tonk music was to supposedly reflect modern love for the first time, Delmore songs were speaking frankly not only to the older, sentimental audience, but to the younger generation who, like themselves, knew the pain and confusion of turbulent emotions.

As the 1930s progressed, the Delmores added more and more hit records to the list of those memorable sides from December, 1933. These included “Nashville Blues” (1936), “False Hearted Girl” (1937), “No Drunkard Can Enter There” (1937), “Southern Moon” (1937), “I Need The Prayers Of Those I Love” (1937), “Weary Lonesome Blues” (1937), “Fifteen Miles From Birmingham” (1938) and “They Say It Is Sinful To Flirt” (1937). With Arthur Smith the brothers recorded “There’s More Pretty Girls Than One” (1936), “Take Me Back To Tennessee” (1936), “Pig At Home In The Pen” (1937), “Walking In My Sleep” (1937), “Beautiful Brown Eyes” (1937) and “Across The Blue Ridge Mountains” (1937). They even had a hit with Uncle Dave Macon, “Over The Mountain,” in 1935. During this time they also published two songbooks of their work: Songs We Sing On The Grand Ole Opry, ca. 1937, containing 43 songs drawn primarily from their recorded repertoire; and Sweet Sentimental Songs From The Heart Of The Hills, published in 1936 with ex-Vagabond Curt Poulton and containing 32 songs, including again most of the Delmores’ hits. Neither book was issued by a regular music publisher, such as Cole or Peer or Forster, but by the artists themselves—testimony to the bad experience Alton had had with his round with the Vagabonds, and testimony to the developing need for a music publisher in Nashville. It would be 1940 before the Delmores would see a folio of their work issued by an established music publishing company.

In January, 1938, David Stone suspended Arthur Smith from the Opry for three months for missing an important show date in west Tennessee, thereby initiating a chain of events that would eventually lead to the Delmores leaving the Opry. Smith and his band, the Dixieliners, was the favorite touring group for the Delmores and his absence meant they had to find another band to go out with. David Stone came to the brothers and told them he planned to audition four different bands on four consecutive weeks, letting them play as guests on the Opry and the Delmores would choose the one they liked best. This band would be hired as a “road band” to back the brothers on personals and tours and would be hired for only a six-month period; “they will never be a genuine act of the Grand Ole Opry,” he told Alton. After listening to four bands the brothers told Stone their choice: the east Tennessee group called the Crazy Tennesseans and led by Roy Acuff. According to Alton, David Stone was surprised, since he considered Acuff’s group the worst of the four bands, but agreed to hire him to fill out the booked show dates. When he wrote Acuff, on February 10, 1938, he painted a different picture; “I am teaming you up with the Delmore Brothers for several personal appearances,” he said. “These boys have tremendous popularity in this territory, but they cannot build or manage their own unit so I think it would be a great combination for the two acts.” By February 19, Acuff was sharing the morning show that the Delmores had on WSM, and on February 20, he and his band backed the Delmores for their first joint date, in Dawson Springs, Kentucky. According to the original deal Stone worked out with Acuff, the whole troupe would travel in Acuff’s station wagon—five members of the Acuff band and the two Delmores— and the gate receipts would be split 50-50, half to the Delmores half to the Acuff band. This seemed to work well for a time, and Alton and Roy even used to sit out in his station wagon and sing old gospel songs between shows.

As Acuff’s popularity soared, he soon was able to carry a tour on his own and he and the Delmores split up. There were mutual influences, though: the Delmores soon recorded songs from the Acuff repertoire, such as a version of “Wabash Cannonball” (1938), “You’re The Only Star In My Blue Heaven” (1938) and “Wabash Blues” (1939). Acuff, on his part, waxed versions of “Walking In My Sleep” (1940) and “Beautiful Brown Eyes” (1940). Soon, though, the Delmores were touring with the Golden West Cowboys, led by Pee Wee King but managed by Joe Frank. Both brothers were impressed by the promotional abilities of Frank—abilities that would eventually land him in the Hall of Fame as one of country’s great promoters—but they knew they were marking time. By the start of the year in 1938, the brothers were actively looking around and writing other radio stations to try to land better jobs. The reasons are complex. Judge Hay, who had returned to work after a long absence, really didn’t get along with the brothers at all and as director of the Artist Service Bureau could almost dictate tours and booking routes. The Opry management made it difficult to supplement WSM work with outside bookings, for instance, the Delmores played the Opry every single Saturday night throughout 1937 and up until their leaving in 1938. Their enforced estrangement from Arthur Smith, one of the few Opry regulars who could match the Delmores in sheer musical skill and creativity, frustrated them, and watching their “temporary” backup band, Acuff, turn into one of the Opry’s hottest stars exacerbated the touring problem. Added to all this were personal problems; both felt that Opry regulars and staff disapproved of certain aspects of Rabon’s life style and this, coupled with an understandable jealousy of the most commercially successful team on the Opry, caused a subtle but continual tension. The brothers were so anxious to leave that they eventually accepted a job at WPTF in Raleigh, a job that had no regular salary, in hopes that they could make it better with personals. In September, 1938, the Delmores put together a band that included former Golden West Cowboy Milton Estes, bass player Joe Zinkan and singer Smiley O’Brien, and, after singing one last Opry performance of “What Would You Give In Exchange For Your Soul,” packed their two cars and started out east on highway 70. It was September and as Alton recalled, “raining and dismal.”

Before the Delmores left, Harry Stone tried to persuade them to stay, but then finally told them, before they left his office, that “the key was always on the outside.” That proved not to be true, though; while the duo did return in 1939 and 1940 for occasional guest appearances, they were never asked to rejoin and by 1939 J.L. Frank had found another duet that were adept at imitating the Delmore sound—the Andrews Brothers. The Opry was history for the Delmores, but the five and a half years they had spent there launched them on a long and influential career. Ahead of them was a dizzying round-robin of radio stations, but a series of hit records with the Brown’s Ferry Four, with Wayne Raney and by themselves. In the 1940s they were to have even bigger hit records with “Blues Stay Away From Me,” one of the cornerstones of the new rock and roll and “Hillbilly Boogie.” Alton would write over 1,000 songs in his lifetime, see them recorded by people as diverse as Grandpa Jones, Tennessee Ernie Ford, Glen Campbell, Doug Sahm and Bob Dylan. He would be elected to country music’s Songwriter’s Hall of Fame and write a remarkable autobiography, Truth Is Stranger Than Publicity. By 1952, the brothers had broken up and Rabon died soon after; Alton continued on in music for a time, even recording for several small labels and working in radio, but he eventually became bitter and died in 1964.