Home > Articles > The Archives > The Briarhoppers: Carolina Musicians

The Briarhoppers: Carolina Musicians

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 1978 – Volume 12, Number 9

For a period of more than 15 years, the WBT Briarhoppers constituted one of the most popular regional country music groups in radio. Sponsored by Peruna, this aggregation achieved such a following in the Carolinas and adjacent states that it sometimes became necessary for two units to keep active on the road simultaneously in order to satisfy the demand for personal appearances. The music and songs of the Briarhoppers included elements of old-time string music, harmony duets, and bluegrass as well as mainstream country music of three decades ago. Until recently, the Briarhoppers had been relatively inactive but as of late their sound has again been heard at bluegrass festivals in the Southeast.

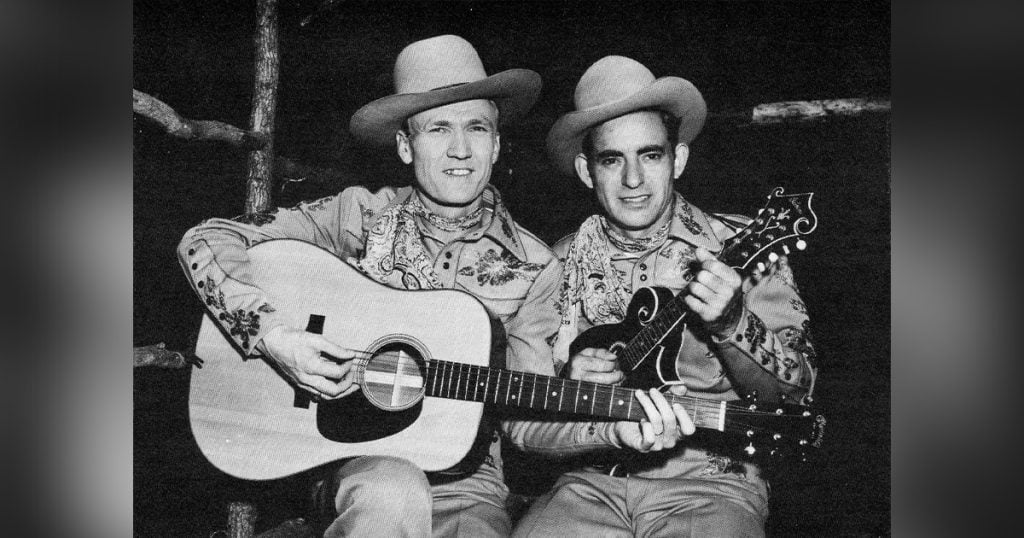

Through a dozen of the Briarhoppers’ best years, the team of Whitey and Hogan formed the nucleus of the group. Made up of Roy Grant and Arval Hogan in real life, this mandolin-guitar duo sang in a style that had wide appeal during the 1930’s and 1940’s. In addition to their radio and personal appearances, Whitey and Hogan cut records, having some 28 issued sides to their credit. These range from old-time duet arrangements to vintage bluegrass.

Arval Hogan, the older and mandolin playing half of the duet, was born in Robbinsville, North Carolina on July 24, 1911. Four years later the Hogans moved to the town of Andrews, North Carolina where Arval’s father directed the choir in a local church and taught his three sons to sing at an early age. During the late 20’s, the Hogan Brothers, Clarence, Garland, and Arval, together with a neighbor on fiddle started a local string band. Since all the Hogans played guitar, it was suggested that Arval get a mandolin. At the time, he did not even know what the instrument was but ordered one from Sears, Roebuck and Company. Subsequently he learned to play it by listening to a record of “Chinese Breakdown” by the Scottsdale String Band. Thereafter Arval played mandolin with the group at “square dances, parties, churches, and family gatherings for a long time.” In 1936 he left Andrews and came to Gastonia where he met both his future wife, Evelyn, and his “life-time music partner.”

The partner, Roy (Whitey) Grant was born at Shelby, North Carolina on April 7, 1916. Whitey’s interest in music dates from his earliest memories. He recalls urging his parents to buy phonograph records of Vernon Dalhart and other old-time singers. At 15, Whitey bought a guitar and had the man from whom he purchased it draw him diagrams showing finger positions for various chords. Church parties and family gatherings provided audiences for Whitey’s developing talents. In 1932 he met Pauline Chapman and after they married in 1935, went to Gastonia to work in a cotton mill. Not long afterward he met Arval Hogan and they have been a musical duet “ever since.”

The two soon began to play at local entertainments and from there went on to regular radio appearances. They first broadcasted on a regular basis on WSPA in Spartanburg, South Carolina as featured performers on Scotty-the Drifter’s program. When radio station WGNC was built in Gastonia, Whitey and Hogan auditioned and subsequently got their own daily quarter hour show at 12:45 each afternoon. Sponsored by Efird’s Department Store, they were called “The Efird Boys.” Later Rustin’s Furniture Store became their sponsor and they did their show live from the department store’s show window. Although they gained considerable local popularity, the duo did not feel secure enough in their careers as entertainers to give up work at the textile mill. Following the show they went to the afternoon shift at the twisting department at Firestone, making the fibers that went into automobile tires. Whitey contends the pair were late for the show only once during the radio days at Gastonia and that was because “Hogan was up at the dime store watching a bunch of goldfish and we forgot we were going to be on the air.” “(I’m Riding On) My Savior’s Train” served as their radio theme song and they performed both secular and sacred numbers.

During the stint at WGNC, Whitey and Hogan made their first recordings. The Decca distributor at Charlotte arranged for them to go to New York in the fall of 1939 where they waxed 16 numbers on November 8. The most memorable songs included a cover of the Blue Sky Boys’ “Sunny Side of Life,” one of the earliest recordings of “Turn Your Radio On,” (preceding the Bill and Earl Bolick version by nearly a year), the sentimental “Old Log Cabin For Sale,” the later bluegrass standard “Gosh I Miss You All the Time,” their own “Answer to Budded Roses,” and the beautiful but seldom heard “You’ll Be My Closest Neighbor.” The trip to New York encompassed some three or four days and the boys recalled that they “were treated like kings” and reimbursed for all their expenses when they got back from New York.

Whitey and Hogan remained at Gastonia until September 1941 when they were asked to join the Briarhopper program at WBT Charlotte. Since the Briarhoppers had a show at 4:30 in the afternoon, the duo switched to working the third shift at the mill for six months until they saw how the new job “shaped up.” They then “followed music continuously for 10 or 12 years,” as a full-time occupation.

The Briarhoppers were already an established group at WBT when Whitey and Hogan joined the organization. The group originated back in the mid-thirties when the Drug Trade Products Company of Chicago wanted to sponsor a country music program at WBT, so they got some “boys together and started a program but they didn’t have a name.” One day Charles Crutchfield, the announcer, was out hunting with some fellows. When they jumped a rabbit and one of the party said “look at that rabbit jump those briars,” Crutchfield hit upon “Briarhoppers” as the name for the band that advertised Peruna. So Briarhoppers they became and Briarhoppers they remain to this day. Actually, the Briarhoppers were but one of several country aggregations sponsored by Peruna around the nation. By 1946, Drug Trade Products Company employed such groups and/or programs as Cap, Andy and Milt in Charleston; the Morning Frolic in Louisville; Cousin Emmy and Her Gang in Atlanta; and the Briarhoppers at Charlotte as well as the Cactus Kids, Uncle Enoch and His Gang, Pete Haley and His Log Cabin Girls, the Bohemian Orchestra, the Bar Nothing Gang, the Haden Family, and the Smiling Hillbillies at other locations. Often, the groups worked under Peruna sponsorship for only six months of the year since Peruna tended to be a popular product only in the winter months when listeners suffered from coughs and colds. In some years, however, the company sponsored the Briarhoppers the entire year. At other times, however, a band might have to seek another sponsor or other means of employment in the “off season.”

Although Whitey and Hogan’s dozen years with the group place them among the more durable members of the Briarhoppers, many other notable musicians worked with the band in their 17 years or so at WBT. A complete history of all these musicians would run into a most lengthy article and outside of those who currently make up the Briarhopers only a few will be mentioned here. William “Big Bill” Davis played bass fiddle with the band through most of its years at WBT. Davis is now a High Point resident and although 84 years of age still plays an occasional show with the Briarhoppers when they play near his home.

Fred Kirby was another key member of the Briarhoppers off and on for several years. Born at Charlotte on July 19, 1910, Kirby worked with Cliff and Bill Carlisle at various times, led his own band-the Carolina Boys-and worked as a solo vocalist. At one time or another, he recorded on most major labels including Bluebird, Columbia, and Decca as well as lesser-known companies like Gotham and Sonora. Fred achieved considerable success in the mid 1940s with his song “Atomic Power,” which was covered on some nine record labels. Kirby also composed “Reveille in Heaven” which is one of Mac Wiseman’s bluegrass standards. He is still active in Charlotte to this day although he has not been associated with the Briarhoppers for more than 25 years.

There were also two “Homer” Briarhoppers. The first, Homer Drye, was a youth who recorded for Bluebird in the late 1930s and continues to use that name to the present day although, like Kirby, he has not been a part of the group for many years. The other was presumably Homer Christopher who waxed a few sides for Decca also in the late thirties. Gib Young was a fine guitar player for the group as was Dewey Price. Eleanor Bryan worked as girl vocalist for some time and also played an able guitar.

Garnett B. Warren, better known as “Fiddlin’ Hank,” served one of the longest stints with the Briarhoppers. Born at Mt. Airy on April 1, 1909, Hank also became interested in music at an early age. He learned to read music (being one of the few traditional performers to do so) and played violin in the high school orchestra. He later learned to play mandolin, tenor banjo, ukelele, and hand saw. Interested in old-time music too, he participated in and won several fiddler’s conventions in the Mt. Airy area prior to organizing a local band known as Warren’s Four Aces. In 1931, he married Inez Turney and then went on the play fiddle with a professional group—Jack Richie and his Blue Ridge Mountaineers.

Hank then joined Dick Hartman’s Tennessee Ramblers, one of the most popular country bands in the Carolinas, who played regularly at WBT. Since this group played a lot of “uptown” and western-styled country music they are not as well remembered today as bands that clung to the mountain styles, but a Crazy Water Crystals souvenir booklet of the mid-thirties suggests that their popularity probably at least equaled that of Mainer’s Mountaineers. Other members of the group at various times included Harry Blair, Kenneth Wolfe and Cecil Campbell, who later became their leader. Hank Warren stayed with the group for about two years, playing on two and perhaps three Bluebird sessions with the band. In 1936, he went to California where the Ramblers made the movie “Ride Ranger Ride” with Gene Autry. After the film’s release, the band toured widely with the picture appearing in theaters.

After leaving the Ramblers, Hank went to WPTF, Raleigh where he worked with the Swingbillies, a group led by Charlie Poole, Jr. In 1937, he returned to Charlotte and joined the Briarhoppers. Fiddlin’ Hank remained with them until 1950. In 1943, Hank sponsored one of the most unusual contests ever held on radio when he suggested that listeners to the Briarhopper program submit names for his newborn son. Some 10,000 fans sent in names and the proud father selected the name, Larry, and awarded a ten dollar prize to the winner.

Another important Briarhopper was Don White who played with the group off and on for several years. White’s real name is Walden Whytsell and he came from West Virginia, being born at Wolf Creek on September 25, 1909. Don first learned to play guitar from his mother and eventually played bass, rhythm and steel guitar. He first came to Charlotte as a musician in 1933 with the aforementioned Blue Ridge Mountaineers playing at WSOC radio. He later returned to West Virginia but came back to Charlotte in 1935 as a member of the Crazy Buckle Busters and working for Crazy Water Crystals at WBT. Later he switched to the Briarhoppers, remaining with them until 1939. On June 19,1936, Don made his first recordings, waxing three solo numbers—“Mexicali Rose,” “Rocking Alone in an Old Rocking Chair,” and “What a Friend We Have in Mother.” He also did two duets with Fred Kirby, “My Old Saddle Horse Is Missing” and “Play That Waltz Again.” Don and Fred left WBT in 1939 for WLW in Cincinnati. Don moved on to KFAB in Lincoln, Nebraska as a single and thence in 1941 to WJJD in Chicago. In 1942, he rejoined the Briarhoppers at Charlotte. The following year he moved over to the Tennessee Ramblers who then worked on the same program. He remained with them until 1946 during which time the group appeared in three films. The first one starred Lulubelle and Scotty and Dale Evans, the second featured Charles Starrett and Jimmie Wakely, and the third was “O My Darling Clementine” with Roy Acuff, Pappy Cheshire, and Irene Ryan.

In 1946, Don returned to Chicago and spent the next six years leading the WLS Sage Riders, a popular western styled group. Don was more influenced by western music than most of the Briarhoppers and worked for stints with Otto Gray’s Oklahoma Cowboys and also with Red Foley. When WLS changed ownership in 1952, the Sage Riders disbanded and Don returned to Charlotte, his wife’s home town. He left the entertainment field for more than twenty years.

Shannon Grayson was probably the most important member of the Briarhoppers in respect to their relationship to bluegrass music. Shannon was born at Sunshine, North Carolina on September 30, 1916. This community was only about ten miles from where Snuffy Jenkins grew up and Snuffy influenced Shannon’s banjo style. Grayson took an interest in music at an early age as his family owned an organ and Shannon humorously contends that he almost drove them away with his playing. Later his father bought him a banjo since he could be sent to the barn with it and rest the ears of the Grayson household from listening to his organ music. He also became adept on mandolin, guitar, and bass fiddle.

Grayson played at a number of local entertainments prior to joining the touring group of one Art Mix who claimed to be the brother of cowboy film star, Tom Mix, in 1936. Later he returned home and worked in the textile mills. About 1937, Bill Carlisle approached him about working with his group on radio at Charlotte. Since Carlisle already had a reputation as a radio and recording artist, Shannon thought “that was the greatest thing I had ever heard, to get to work with somebody like Bill Carlisle and be on the radio and play shows and get paid for it too. That was too good to be true!” Shannon played with Bill at WBT, Charlotte, WWNC, Asheville, and WCHS, Charleston.

After the group worked in the West Virginia capital for some time, Bill took them to New York where he scheduled a Decca recording session. Cliff Carlisle met them there and the brothers recorded both together and separately. That session proved to be the first of several that Shannon Grayson would do with the Carlisle Brothers on Decca and Bluebird. On these recordings, Shannon usually played mandolin but occasionally used a five-string banjo. Among the many songs recorded by this group include an early version of “Footprints In the Snow,” “Two Eyes in Tennessee,” and a number called “Are You Going to Leave Me, Lil?” which featured some wild mandolin work and comes quite close to bluegrass. Most of this recorded repertoire features a lot of mandolin along with Cliff’s Dobro stylings.

Following the initial Decca session on which Shannon played, Bill and Cliff reunited for radio work and the Carlisles went to WNOX, Knoxville. They remained in the east Tennessee city for several years. Shannon stayed with them until 1943 playing on the Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round, early morning radio shows, and hundreds of personal appearances. Of the latter, Shannon recalls the most memorable as being in Harriman, Tennessee where they worked a show with Bing Crosby. Dixie Lee Crosby, Bing’s first wife, called Harriman home and the couple had been slated to attend and entertain as had the Carlisle band. Dixie Lee developed an illness and failed to appear although Bing came and the Carlisles ended up providing musical backing for him. Shannon recalls that things worked pretty well with “a bunch of hillbillies” accompanying Hollywood’s most popular crooner and that everyone was congenial.

In 1943, Shannon Grayson came to Charlotte and joined the WBT Briarhoppers. He has more or less been part of the group since that time except during those years when he led his own band, the Golden Valley Boys. This combination worked together in the late 1940s and early 1950s, guesting on various radio shows while cutting some vintage bluegrass for the King and RCA Victor labels.

The Golden Valley Boys consisted of Shannon Grayson playing banjo and singing lead, Dewey Price on guitar and tenor vocal, and Millard Presley doing the mandolin work and baritone singing. Harvey Raborn sang bass in the quartets but played no instrument. A studio bass player was used on their sessions. Tommy Jackson fiddled on some cuts and an electric steel was used on part of the Victor recordings. In all, the Golden Valley boys had four sides issued on King and eight on Victor.

Most of the band’s repertoire consisted of sacred material, especially quartets. Shannon did some banjo instrumentals like “Earl’s Breakdown” and “Flint Hill Special” and the group performed some secular material like “Work Is All I Hear” and “Roses and Thorns” which they recorded on Victor. Some of the best known sacred songs included “If You Don’t Love Your Neighbor” which Carl Story also recorded, ”I Like the Old Time Way,” “Since His Sweet Love Rescued Me,” “Sunset of Time,” “Childhood Dreams,” “The Secret Weapon,” and “Pray the Clouds Away.”

Although the Golden Valley Boys had no regular radio show, they managed to keep about as busy with showdates as those groups that did. They guested regularly on the Briarhopper program and other radio shows. Somewhat later they appeared often on the Arthur Smith television program and other radio shows. Such appearances together with their recordings gave them a good drawing power in the Carolinas.

Meanwhile, all during the forties, the Briarhoppers with Fiddlin’ Hank and Whitey and Hogan’s duets continued to be very popular throughout the decade. During the war years the band participated in bond drives and entertained servicemen while continuing to play regularly in auditoriums, theaters, and schools. Sometimes they were booked on package shows with artists from the Grand Ole Opry and other country music radio jamborees. One memorable night they vividly recall was June 6, 1944—D Day—when they were playing in Norfolk, Virginia with Ernest Tubb and Pee Wee King’s Golden West Cowboys. Over the years, Whitey and Hogan played shows from Georgia to Washington D.C. and Lexington, Kentucky with the latter being a guest appearance on the Kentucky Barn Dance. For their “outstanding accomplishments” in selling (war) bonds Whitey and Hogan received a citation from Secretary of the Treasury, Henry J. Morganthau.

After World War II, Whitey and Hogan also had the opportunity to make further records. They waxed eight songs on the Deluxe label about 1946 of which six were issued. Those released included a cover of Molly O’Day’s “Tramp on the Street,” one of their own compositions entitled “There’s a Power Greater than Atomic” (an excellent topical song of the period) and Karl and Harty’s old number “I’m Just Here to Get My Baby Out of Jail” together with three lesser known songs—“You’ve Had a Change in Your Heart,” “Bear Creek Hop,” and “I’m Just a Used to Be.” (The latter a completely different song not to be confused with the Bill Monroe composition with a similar title.) In addition to Whitey’s guitar and Hogan’s prominent mandolin, accompaniment on the session included Big Bill Davis, bass; Roy Rector, steel guitar; and Sam Poplin, fiddle. Two numbers have never been released from this session, one of which was “The Bible My Daddy Left for Me.” The Deluxe recordings constitute what may be Whitey and Hogan’s best recorded efforts.

In 1947, “Whitey and Hogan’s Mountain Memories” song book came off the presses of Bourne Music Publishers of New York. This coincides with their peak period of popularity during which time they appeared not only on the Briarhopper program but also on WBT’s “Carolina Hayride” and “Dixie Jamboree.” On Sunday morning, together with Arthur Smith and the Cracker Jacks, the Tennessee Ramblers, and the Rangers Quartet, Whitey and Hogan were regular features on “Carolina Calling” which went out to a national audience over the CBS network. The Briarhopper program, however, remained their major source of popularity. Whitey and Hogan jokingly contend that the show’s appeal stemmed from being broadcast just before “The Lone Ranger” came on the air, and that listeners tuned in to their show so they wouldn’t miss the adventure show.

Whitey and Hogan cut more records later in the decade. They had one release on the Cowboy label, both sides of which featured numbers from their song book. “Jesse James,” their most popular tune, was an excellent harmony duet which featured Shannon Grayson on bluegrass banjo and Bill Davis on bass. This number, together with Shannon Grayson’s “If You Don’t Love Your Neighbor,” is currently available on Rounder Records’ “Early Days of Bluegrass #1.” The other side, their own tune, “I Have Tried but I Have Failed” had a more typical guitar-mandolin sound. The duo also recorded for Sonora records in New York with four sides being released. Hank Warren’s fiddle and Bill Davis’ bass complemented their own guitar and mandolin. A cover of the widely popular “Have I Told You Lately That I Love You” by Scotty Wiseman did very well, with the reverse being a novelty tune, “Mama I’m Sick.” The other Sonora release was “Talking to Mother” and “I’m Longing for My Sweetheart,” a pair of good sentimental numbers.

Whitey and Hogan also provided musical backing for three other artists on record. They helped Dewey Price, then a member of the Briarhoppers, do a session for Majestic. Released as Dewey Price and the Blue Ridge Mountain Boys, two of the titles cut have entered bluegrass repertoires although the accompaniment on the records is somewhere between western swing and bluegrass. Leon Rusk’s composition “Air Mail Special” originally done as a smooth western swing number eventually became a bluegrass classic as performed by Jim and Jesse while Vaughn Horton’s “Sold Down the River,” also recorded by the Blue Sky Boys, finally received a typical Bill Monroe treatment in 1960. Whitey and Hogan also helped Majestic’s A and R man, Riley Shepherd, on a session and assisted fellow Briarhopper Fred Kirby on some of his Sonora recordings. In addition, the Blue Sky Boys recorded one of Whitey and Hogan’s songs, “I’ll Take My Saviour By the Hand,” and the Buchanan Brothers did a cover of “There’s a Power Greater Than Atomic” on RCA.

The forties, however, proved to be the last full decade of the golden age of radio. The Briarhopper program terminated in 1951 although Whitey and Hogan continued as regular performers on television until 1953. Gradually, various members of the group went into other occupations. Shannon Grayson became a carpenter and cabinetmaker specializing in making bank furnishings and fixtures. Hank Warren became a photographer working for WBT-TV. Whitey and Hogan, faced with remaining in Charlotte where their children were in school or continuing radio work in a new location, chose to give up show business. As Whitey Grant puts it, “Our children at that time could go to school and go to church and not have to cross the

streets so I started driving a city bus here in Charlotte.” Somewhat later he entered the postal service becoming a city letter carrier. Arval Hogan entered the restaurant business briefly in West Palm Beach, Florida, but returned to Charlotte and sold insurance until he, too, became a mailman. For some 20 years they played music mostly for their own amusement or occasional local functions.

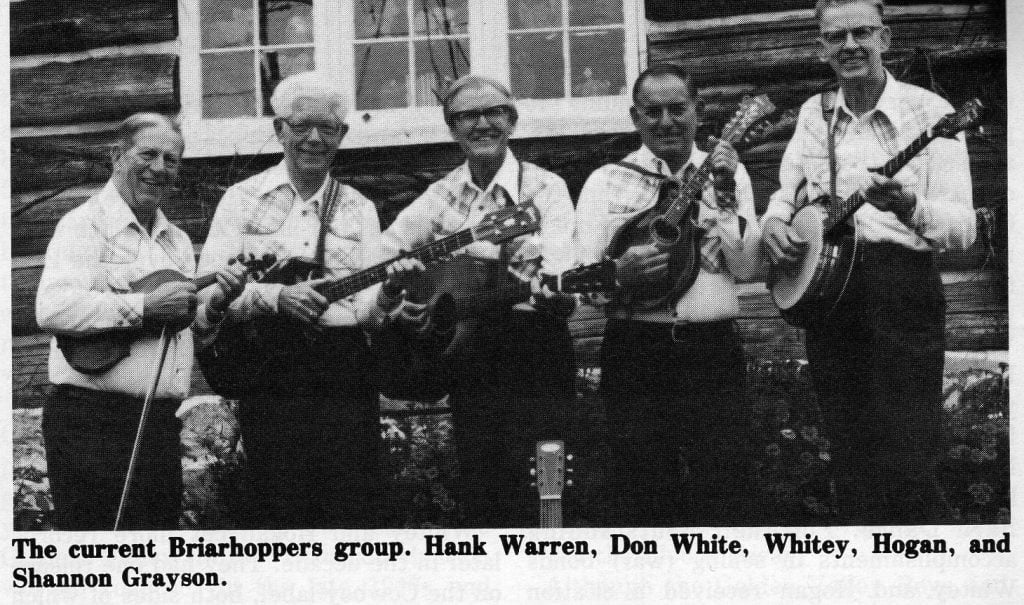

In the early 1970s, five members of the Briarhoppers decided to get back together—Whitey Grant, Arval Hogan, Shannon Grayson, Hank Warren, and Don White. The Rounder Records people sought them out in May 1973 to get background data for their “Early Days of Bluegrass” series and afterward they began to play more frequently. Renewed interest in old-time, bluegrass, and their brand of country music together with a general infatuation with nostalgia gave them a new audience while many of their old fans fondly remembered them.

In the last two years, the Briarhoppers have appeared at the Snuffy Jenkins Bluegrass Festival and also at other festivals in the Carolinas. They have also played at schools, churches, senior citizen centers, and been on radio and television again. Recently, Old Homestead records released an album made up of material from their old records, radio transcriptions, and home recordings. Some of the hitherto unreleased numbers available on this record include an excellent rendition of the Bailes’ song “Dust On the Bible,” the Delmore’s “Lonesome Gamblin’ Man,” and a song foretelling the energy crisis entitled “The Old Grey Mare Is Back Where She Used to Be.”

In December 1977, they did a new session for John Morris of Old Homestead from which two albums are slated for future release. In all, the Briarhoppers are finding considerable satisfaction with their rejuvenated careers in traditional country and bluegrass music. Hank, Don, and Hogan are now retired from their jobs although Whitey and Shannon continue to work. They are already booked on several bluegrass festivals for 1978.

Over the past four decades the various members of the Briarhoppers have made notable contributions to old-time, bluegrass and country music. Whitey and Hogan with their harmony duet and Shannon Grayson with his pioneer bluegrass quartet are particularly exceptional. Fiddlin’ Hank and Don White contributed to both old-time and western music. Today, all five are continuing to entertain in the tradition of which they have so long been a part.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

The Legendary Briarhoppers continue to perform in its 91st year.