Home > Articles > The Archives > The Boys From Indiana with Paul Mullins and Noah Crase

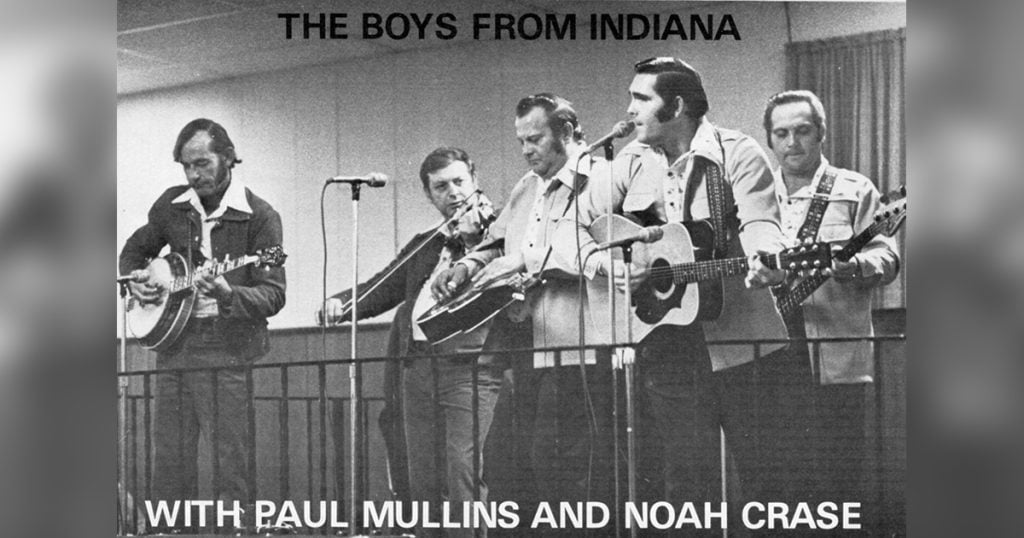

The Boys From Indiana with Paul Mullins and Noah Crase

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1976, Volume 11, Number 5

Not since the introduction “Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and All The Foggy Mountain Boys” last rolled off the tongue of announcer T. Tommy Cutrer has the name of a bluegrass band been longer or more talked about than “The Boys From Indiana with Paul Mullins and Noah Crase.”

Sure, it’s a long title, but it’s confused more often than it should be, by fans and promoters alike. The point of this long name is that all of the members have significance on their own, and experience earned separately, and these things are mentioned in the old, fair sense of “credit where credit is due”.

I

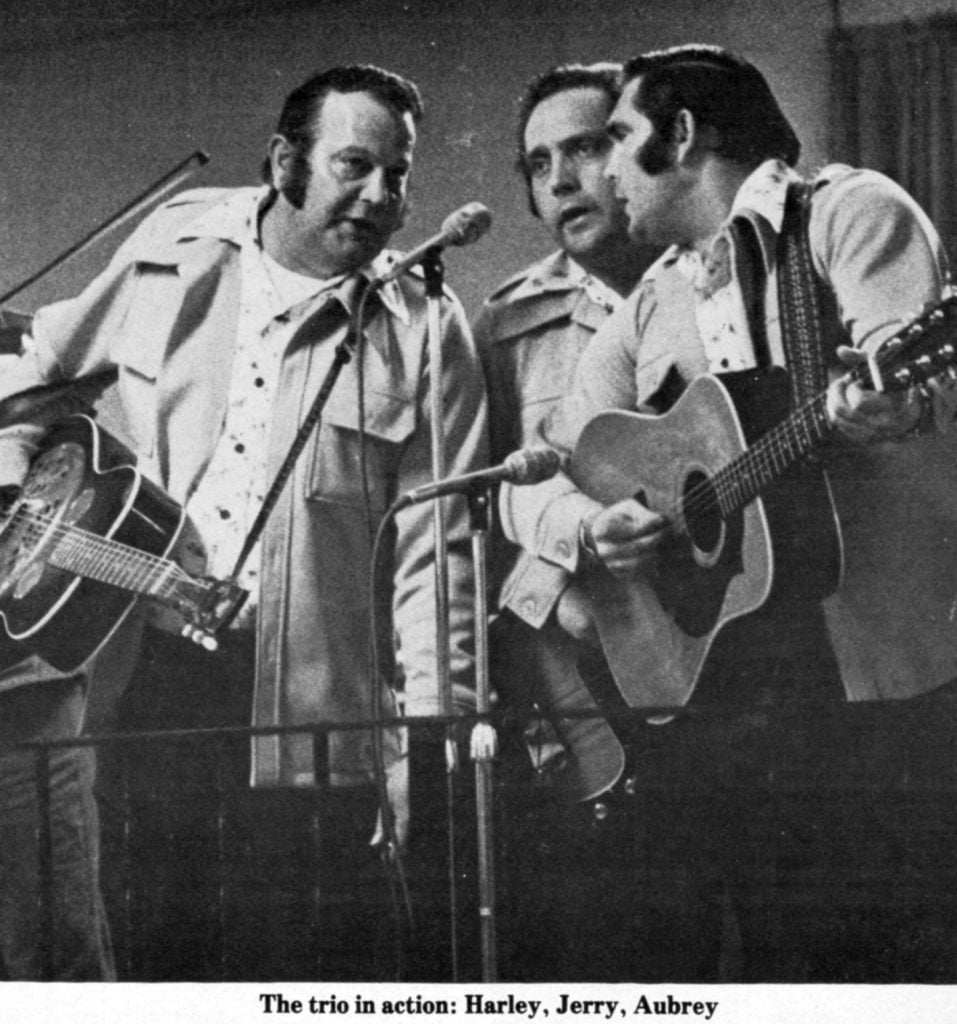

Three-fifths of the band, The Boys From Indiana trio, is made up of family members who have been playing together a long time, beginning as boys on a farm in Indiana, and many of their childhood experiences are reflected in the music they write and sing.

Harley Gabbard is Aubrey and Jerry Holt’s uncle, but they grew up together in a family in which nearly everyone played an instrument and sang. The whole family would sit around and listen to The Grand Ole Opry on a battery-powered radio, and then would play and sing far into the night, and the boys listened to the adults still singing after they were sent to bed. They remember the World War II songs, those of Ernest Tubb and Roy Acuff, and “Footprints In The Snow”, and they particularly liked Hank Williams’ songs.

By the time they were twelve or thirteen, Aubrey and Harley were sneaking off to sit in the corncrib and play guitars and sing. Harley got started on guitar, then banjo, fiddle, and French harp. He once made a fiddle bow out of an elm branch and cut hair for it out of the tail of his cousin’s horse.

Even the reaction that brought didn’t discourage them, and when they got into their middle teens, they would sit in on the family singing sessions, and then go to practice with a cousin, Earl Gabbard, who played Travis-style electric guitar. Earl had had an offer to travel with Merle Travis, but he didn’t take it seriously, so after Harley and Aubrey got old enough, the three of them played in bars together.

In 1955 and ’56, when Harley had just started playing banjo, Jimmy Skinner had a radio show over WNOP, Newport, Kentucky, which originated from his old 5th Street record shop in Cincinnati. Bill Price and Bobby Simpson were playing there, and Harley “Would go down to try to learn hot licks in the back room”. It was there he and Aubrey met Jimmy Skinner and began a friendship that was to last for a long time.

“Jimmy Skinner is one of the best friends I ever had,” Harley says. “He did more for me. I worked for him for four or five years off and on when I was needed.”

During 1957, when Aubrey and Harley were working as “The Logan Valley Boys”, they began playing with “The Laurel County Boys”, consisting of Curley Tuttle, Virgil Joseph, Danny Brockman, and Hubert Cox, a fiddler from Waycross, Georgia, who lived in Hamilton, Ohio.

The two groups combined to make up “The Logan and Laurel Valley Boys”, and played a radio show every Saturday in Hamilton, Ohio, over WHOH. A single was recorded on the Excellent label, Aubrey and Harley’s composition of “Family Reunion” b/w “Let The Saviour In”.

The record was played a great deal in the Cincinnati area, reaching #4 on the local charts. After that they cut several singles for Starday, all under slightly different group names. Two they remember are “You’ll Never Find Another So True” and “Burning The Strings”.

According to Aubrey, when rock and roll was new, “You couldn’t give bluegrass away”, and Aubrey entered the Navy. Harley played for about a year and a half with Arthur and Jesse Burns, “The Burns Brothers”, and then headed South to join Aubrey, who was stationed in Jacksonville, and Hubert Cox, who had returned to Way cross, Georgia.

The three of them worked out vocal harmonies and played in clubs, at dances and birthday parties, and managed to work nearly every weekend that Aubrey was free.

About 1962, Aubrey and Harley returned to Indiana, and not long afterward joined Hylo Brown, with Harley on Dobro and banjo, and Aubrey on bass.

The first time Aubrey played bass was on the Wheeling Jamboree, and then they played a fair in West Virginia in a place where “You wouldn’t think there were thirty people in the county, but cars were lined up on both sides of the road for three or four miles in each direction.”

Charlie Moore and Bill Napier were on that show, as was Jimmy Martin, with Paul Williams, and when Jimmy sang “Lord, I’m Coming Home”, Aubrey says, “It made our hair stand on end”.

Aubrey’s tenure with Hylo was short, but Harley continued on banjo and Dobro for about a year, and for part of that time, Hylo’s band also included Melvin and Ray Goins and Curly Ray Cline.

In the mid-60’s in Cincinnati, the Ken-Mill tavern was home for a bluegrass band which changed personnel from time to time, but was always of a high quality. Some of its members were Walter Hensley, Jim McCall, Benny Birchfield, Earl Taylor, Boatwhistle and Junior McIntyre, and Harley Gabbard. Countless musicians sat in or played short stints, and among these were Ralph “Robby” Robinson, Noah Crase, and Paul Mullins.

Toward the end of 1965, a single of Harley’s “Divorced But Not Free” was recorded for Rem, b/w his “Uncle Bill’s Still”. Jim McCall played guitar; Junior McIntyre, banjo; Benny Birchfield, bass; with Harley on Dobro and Paul Mullins on fiddle.

During one of the band’s re-organizations, Walt Hensley and his brother Jim, with Harley, Aubrey, and Frankie Short on mandolin, formed another band which worked around the area as many as five nights a week, in three different clubs.

“Walter,” says Aubrey, “Is one of the finest banjo players I ever saw. He could follow nearly anything, like slow stuff, and could play any request as well as hard, driving bluegrass.”

Walt had recorded an experimental, non-bluegrass record with Boots Randolph, and after its success he went back to Baltimore. Aubrey and Harley continued to play, but “When the picking got thin and I had lots of kids to feed”, Aubrey took a day job, and quit playing for a couple of years.

During this period Harley went to work for the Osborne Brothers, playing guitar and singing. “The first week I played with them we did nine shows, including TV shows and The Black Poodle with Chill Wills and Mel Tillis.” Harley at that time was playing three-finger style, but after that first week, “I got a straight pick!”.

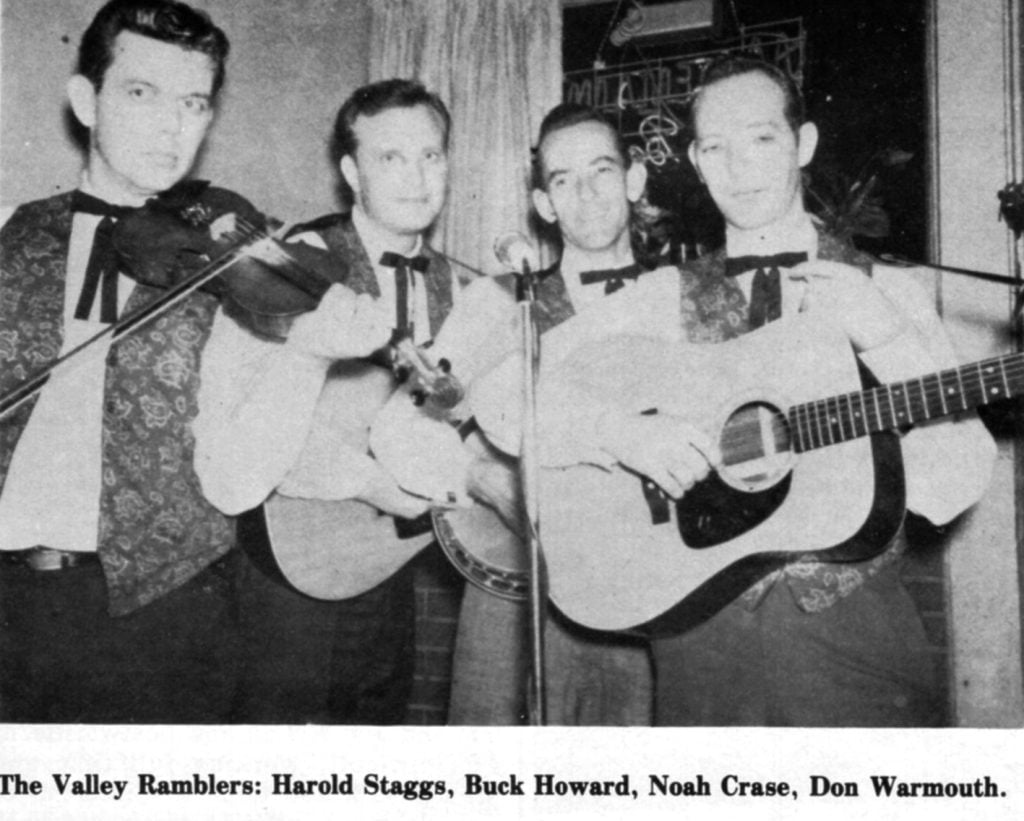

Harley also worked with the Goins Brothers, and with The Valley Ramblers (at that time, Paul Mullins, Noah Crase, Jerry Holt, and Don Warmouth) and recorded with J. D. Jarvis.

Toward the end of 1968, Aubrey was “About to go crazy after two years without playing,” and quit his job to get a country band started. The band had an electric guitar and drums, in addition to Aubrey, Harley, and Jerry, and played an honest kind of country music, influenced by Merle Haggard, and featuring Osborne Brothers style harmony on the trios.

Harley had recorded an album of his own in 1970, with Aubrey, Jerry, and Rusty York on electric guitar, and in 1972, he went back to work with The Goins Brothers.

Paul Mullins, at this time, was working with the Nu-Grass Pickers (Sid Campbell, Noah Crase, and Don Edwards) and when there was difficulty in getting the distant members together for a date, he would call on Aubrey, Harley, and Jerry to fill in. If they were available, he introduced them as “Those wild boys from Indiana”, and the name stuck.

While the group at this time was very loose-knit and temporary, and they all had other commitments, it included the components of today’s band: Aubrey, Harley, Jerry, Paul and Noah. They recorded a gospel album on Jewel, primarily to have some albums to sell, and for Paul to sell on the radio.

Early in 1974, Aubrey, Harley, and Jerry had a serious talk, and decided that if they were ever going to form the bluegrass band they had dreamed of, this was the time. They would drop country music entirely, because, to quote Aubrey, “There are only dances for country bands, and you can play bluegrass to people who listen to the music.”

While they were trying to put a group together, Paul Mullins called Jerry looking for a bass player, and they decided to join forces. The five of them were back together again, this time permanently.

II

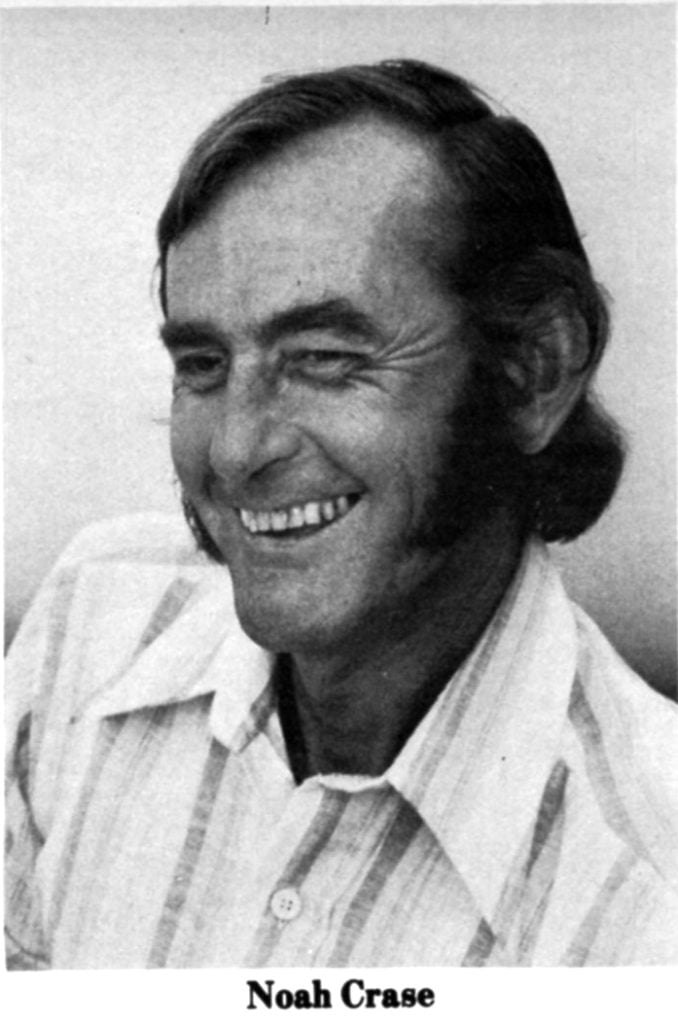

One of the reasons for the band’s popularity and increasing fame is the superlative banjo picking of Noah Crase. Long known as one of the outstanding banjo players in the Midwest, Noah has influenced musicians throughout the country. He was born in Barwick, Breathitt County, Kentucky, and started playing on an open-back banjo belonging to his father when he was about eight years old.

His father played an old style of banjo, as well as fiddle, and once won a Vega Whyte Laydie in a contest in Jackson, Kentucky. He told Noah, “Timing is the most important thing about your music”, perhaps the best advice any young musician can receive.

Noah played mandolin and guitar, but, having no one of his age to play with, began to follow around an adult guitar picker. He learned a few things on the guitar from him, and later played banjo with him, still in an old style similar to the way his father played.

When the Crase family moved to Ohio, Noah was about 13, and he started trying to play banjo 3-finger style. “I had heard Scruggs (on record) in Kentucky and couldn’t figure out what he was doing. I thought maybe he was using a straight pick!”

After his father traded a shotgun for an S. S. Stewart banjo with a resonator, Noah started picking in earnest. He had bought a dozen Flatt and Scruggs 78 rpm records, and sat in front of the record player by the hour, trying to find out what Scruggs was doing.

“I played every spare minute. Played before school thirty or forty-five minutes every day, then after school before going to work in a grocery store, and then after work until I went to bed. Nobody ever showed me anything. I started with two fingers, progressed to three fingers, just from listening to Scruggs.”

His first picking job came when he was 17 or 18, when he and a guitar player went to Monroe, Ohio, south of Franklin, and worked in a club. “We played Friday night for $3.50 each-or maybe that was for both of us!”

That Saturday night they played and made $15.00 in tips, so the next weekend Noah went to the Hilltop Tavern, where a group was playing regularly. Hired for the astronomical fee of $20.00 a night, he worked for eight months, and ordered an RB-100 Gibson.

It was there in the Hilltop Tavern that he met Frank Wakefield and Red Allen. The three of them went to Dayton and played in some of the clubs there, and Johnny McKee and fiddle player Bob Dooley sometimes worked with them.

“Musicians swapped around a lot,” Noah remembers. Three 78 rpm records were made with Red Allen, Noah Crase, and Claude Stewart (mandolin) on the Kentucky label as “The Kentuckians”, of which “Preachin’, Prayin’, Singin’ ” and “Paul and Silas” have recently been re-issued by Rounder. Another they recorded was “Boat of Love”.

A dub of “Two Lonely Hearts” was made with Red and David Harvey (mandolin) which was later recorded by the Osborne Brothers with Red Allen. In 1954 Noah left to work with Bill Monroe for six or eight months, and when he returned to Middletown once again teamed up with Red Allen. Carlos Brock and “little” David Harvey were part of a group that played shows in the Eastern Kentucky area, beginning with a performance in Red Fox, Kentucky, near Hazard. They played in a theatre in Jackson, Kentucky, and had a radio program in Whitesburg.

Jimmy Martin called Noah while he was on the road, and convinced him to come back to Southwestern Ohio and work with him, Smoky Ward, and Red Taylor. Later the four of them and Hylo Brown went to Detroit and got a job, but when they were told they had to join the union to work there, and they were not able to get into the union, they returned to Middletown, and Jimmy went to Louisiana.

About 1955, Noah went to Portsmouth, Ohio, to work in the 440 Club, where he played for five or six months. Red Allen and Frank Wakefield came and got him, and they then played at the Circle Bar in Dayton and several other clubs in Southwestern Ohio.

His second stint with Bill Monroe came in 1956, when Monroe had scheduled some network TV shows. Again, he stayed only a short while.

“Elvis’ music was popular. You couldn’t get a job with a banjo. I played electric guitar a year or two, and took my banjo along just in case. But there was nobody around to play ’grass with.”

Finally, about 1961, Earl Taylor called from Cincinnati to ask Noah to work with him and Jim McCall and Boatwhistle. It was difficult, working full time and driving back and forth to Cincinnati to play music four nights a week, but Noah played with them about three months.

After that, Noah was working in a factory at night, and couldn’t play music on a regular basis. He did get together with Don Warmouth and The Valley Ramblers to cut their Strictly Bluegrass album on Jalyn, and to play with the group as time permitted. Bobby Gilbert played bass, and Harold Staggs and Benny Williams both played fiddle during that time.

In 1964, just after he came to Middletown, Paul Mullins began to be included in some “friendly picking” sessions, and it was at one of these that he and Noah became acquainted.

Noah, Bobby Gilbert, and Don Warmouth started working with Paul in Dayton, Cincinnati, and Middletown, and recorded two single records, “Sweetheart of Mine” b/w “I’ll Always Be Waiting For You,” and Noah’s “I Can’t Go On This Way” b/w “Long Gone” on Jalyn. Jerry Holt played bass on the session.

Later, Paul and Noah got together with Sid Campbell and Don Edwards, from Columbus, Ohio, to form the Nu-Grass pickers. While the group got along well together, jobs were plentiful, and their only album was highly praised, it was awkward for musicians living at such a distance from each other to get together to practice, and it was hard to work out performance dates as well. They disbanded just in time, however, for Paul and Noah to join up with “Those wild boys from Indiana” to create a new and more permanent band with a new sound.

III

Paul Mullins was the catalyst that brought them together. A well-known disc jockey and outspoken bluegrass believer in Middletown, Ohio, Paul is also a fine fiddle player who has worked and recorded with such notables as The Stanley Brothers, Charlie Moore and Bill Napier, and The Goins Brothers, among others. (See B. U., December 1975, “Paul Mullins: Musician, Disc Jockey, and Bluegrass Influence”)

At one time or several, Paul had worked and recorded with Aubrey, Harley, Jerry, and Noah, and the five of them had been together on many performances and one album. It was only natural that they should get together again, and after much discussion, Todd’s Fork, Renfro Valley, and several other festivals were booked for the summer of 1974. Harmonies and breaks were rehearsed, and Aubrey’s new songs began to take their place in the repertoire of the group.

The expert, traditionally oriented instrumentation of Paul, Noah, and Harley offers counterpoint and drive that complements the carefully plotted harmonies of the trio.

“We try to get harmony on every word, if we can,” Aubrey says. “We work it out slowly.”

Harley, who is gifted with nearly perfect pitch, is very particular about harmony. Their trios change patterns, sometimes in the middle of a song, with the three of them changing parts to fit the song or the situation.

All of the members of the group have strong voices, and although Aubrey does most of the solo singing, Harley, Paul, and Noah each take their turn, providing part of the strength and variety of the band’s performances.

When they were approached by Bob Trout (of King Bluegrass Records) at the Todd’s Fork Festival, they began to work out the material they would record on their first session in September, 1974. (“Atlanta Is Burning!” KB-530) Aubrey’s new songs were featured in that album, and have been a major part of their show ever since.

“We can’t do Lester and Earl’s stuff and have everybody else do it too,’ Aubrey explains, “And nobody can do it as well as Lester and Earl did anyhow!” On festivals, about 75% of their performance is made up of new material.

Two additional albums have been recorded for King Bluegrass, (“Bluegrass Music is Out of Sight,” KB-539 and “One More Bluegrass Show,” KB-545) and another session, probably for an instrumental album, will be scheduled as soon as they can find the time.

Aubrey is enthusiastic about their music. “The main thing we’re interested in is the trio and the new material that everybody won’t do. Paul and Noah are good musicians, and they like some of the older stuff which makes a nice change. We play more older stuff in bars and newer stuff on festivals. We try to mix up shows on festivals. Although we’re playing in different places, there may be the same people there. We don’t want to repeat, but we have to have a basic framework to build on.”

“Our group just needs exposure,” Paul says. “We can pick as good as anybody. We have a lot of pride in the group, and have our own material and our own ideas. The trio gets stronger all the time, too. (During a recent performance of)…“Life’s Railway To Heaven,” I like to froze to death. I thought I was going to cry right on stage!”

Paul’s involvement and excitement are shared by the rest of the band, and Aubrey speaks for them all when he says, “We have fun playing. When it gets to be work, it’s no fun.”

It is obvious when they are on stage that these people are having fun-and their audiences are too. Perhaps the most interesting thing to watch about them is the vitality and exuberance of their team effort; five individuals, each bringing his experience and expertise to the group: The Boys From Indiana, with Paul Mullins and Noah Crase.