Home > Articles > The Artists > Talking Chicago Bluegrass

Talking Chicago Bluegrass

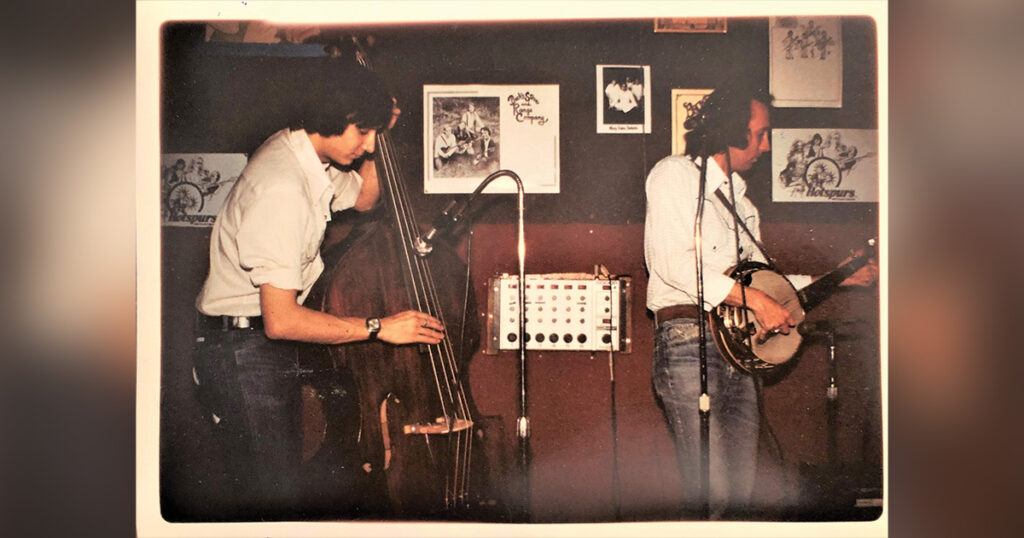

with Greg Cahill and Ben Wright

To understand how bluegrass in Chicago has changed over the years, I had the pleasure of chatting with two of the best banjo players based in the city. I spoke with Ben Wright of the Henhouse Prowlers, a progressive-leaning bluegrass band with an international and educational focus entering its third decade. We sat down with his mentor Greg Cahill of the IBMA award-winning Chicago staple Special Consensus, which Cahill co-founded in 1975. Our discussion was wide-ranging—from the history of the music in Chicago, to the exclusion of musicians from places outside of the south in the name of traditionalism, and the way the economics of making music has changed through the years. Their experiences reveal how these things are connected: making the bluegrass tent bigger, and cooperating with musicians in all corners of that tent, makes it easier to get by. Here, we see Wright as a mid-career artist experiencing much of what Cahill is reflecting on as an established artist. I edited our conversation for length and clarity.

Heather Grimm:Having seen you both in concert, I’ve noticed how you reference the fact that you’re from Chicago on stage, usually in a somewhat defensive way. How has being from Chicago become a part of your “brand identity”?

Greg Cahill: For the first 30 years, there were places that wouldn’t hire us because we were from Chicago. It had nothing to do with the music. This was mostly in the south, mostly the bigger festivals at the time. But most of the time they wouldn’t say it explicitly. But they would say that in Nashville, though. The first time we played the Station Inn was 1981. It took forever to get booked there because we were from Chicago. We had a new mandolin player that was filling in for the summer. We got there at seven-thirty to rehearse for a nine o’clock show. When the manager came back and said “Greg, there’s somebody here to see you,” I said, “Forget it,” because we had never played together and we were playing the Station Inn! Every minute of rehearsal counts. She said “No, I really think you should come out here.” So I go out there and here’s this powder blue suit, white Stetson, a beautiful blonde woman on his arm. He said, “I’m Bill Monroe and I came to see how you play my music in Chicago.” He said he could only stay for one set.

HG: Talk about pressure!

GC: I went back and told the band that we’ve never played together and Bill Monroe is sitting in the front row. [Greg yelps, imitating their panic.] But we did it, and he stayed. We talked to him the whole intermission.

Ben Wright: What did he say?

GC: He said he liked the way we were putting his music across, or something like that. So back then, you had to play three sets at the Station Inn. He stayed for that break, and then he stayed again, and stayed until the end and left.

HG: He must have really liked it.

GC: Well, later the person who did sound for us asked, “Why didn’t you ask him up to play with you?” I would never have the guts to do that. He said that Bill stayed because he was waiting to be asked up. But then we agreed that he wouldn’t have stayed for two breaks if he didn’t want to just hang out. That gave us legitimacy as a band from Chicago, because Monroe came out and stayed. The thing is, bluegrass always had a good following in Chicago. That was the point of our recording Chicago Barn Dance [2020], to show people that this has been around here for a long time, you just didn’t realize it. Ben, I’m sure you experienced that attitude: “You’re from Chicago, we can’t take this seriously.”

BW: Oh yeah, even to this day I still get comments like that semi-regularly. They’ll say, “So how did a bluegrass band get started in Chicago?” And I think about the Old Town School of Folk Music that’s been there since 1957. You need to be a nerd to know the history, you know, but it’s there.

HG: I think about how closely people associate the blues with Chicago, and it’s such a similar story to bluegrass about how people came from the south, settled in places like Chicago, and made music. And yet something about bluegrass, it just didn’t stick.

BW:Yeah, I think it’s the schism between the north and the south, and how that music was identified as being southern music, even though it’s not anymore.

GC: When we were getting started there was cross-pollination with the blues. I played on some Eddy Clearwater records. When he called me up to ask me to play with him, I said “Wait, I play the banjo!” and he said “Yeah, I know.” I found out that he and a couple of the blues guys in Chicago knew more about bluegrass than a lot of people playing bluegrass because they grew up in the south and that’s what was on the radio.

HG: Wow, so the two genres have influenced each other more than most people realize. It seems to go against the traditionalist grain of keeping tight boundaries around what does and doesn’t count as bluegrass.

GC:When I was on the IBMA board, the question was always how to incorporate the young people without losing the old people. People would say “describe bluegrass—what is this tent and how big is it? And how far will you go before you stop calling it bluegrass?” People would hate some versions of the music that didn’t always have a banjo, for instance. For me, I would always push the real traditionalists on the question of whether you had to be from the south to play this kind of music. Let’s look at the people who are really making money doing this. Alison Krauss is from Champaign, Illinois. Bela Fleck’s from New York City. Tony Rice—okay, he’s from Virginia, but he grew up in California.

BW:And Seldom Scene in D.C.

GC: These bands were making the money. Then I started thinking twice about making those arguments in those IBMA meetings. But there’s so many young people who at least show up now.

BW: I had a less than great experience when I went to IBMA early on, which I think was 2006 or 2007, but I want to provide some context. I didn’t have the perspective I do now, which is that if it’s only your third year being a band, and you’re going to something like IBMA, you might feel like you didn’t get a lot of gigs out of it, no matter where you’re from. But you absolutely have to go. You need to show everyone that you’re serious about being in the mix. Shake hands with the movers and shakers, be seen at the showcases of bands you love and bands you’ve never heard of before. Be part of the scene and the scene will start including you.

GC: It’s the same at the festivals. Many of them have started incorporating different types of bluegrass. Most of them now have more than one stage. They’ll have a youth stage, or a late-night stage for the more progressive stuff.

BW:We played Thomas Point this year, which is in Maine. It’s a great festival and we played the mainstage. Everybody loved us, but they’ve rebooked us for next year as a late night band. It’s great that they rebooked us…

HG: But it shows where you stand as an artist.

BW: We also played a more traditional festival and they were displeased with us because we were too loud.

GC: I don’t think they’ll hold it against you.

BW:We have to treat shows differently depending on the audience. Sometimes we’re playing a listening room and we can tell stories from our travels and people are really into the narrative of the band. Other times we’re at a festival and people want to dance. That doesn’t mean we change our show, but we might move between songs quicker and talk less. It’s a puzzle and one of the things I love about being in a band. You can’t win them all though. That same trad festival also had people complaining on social media about our instruments being plugged in.

GC: Still?

BW: Yeah, it’s been rattling around in my brain ever since to be honest. I have a mic setup fully built and ready to go, but I like my plug-in setup so much. It’s easy and I think it sounds pretty close to acoustic. That being said, I’m probably going to change it soon.

HG: What I’m hearing from both of you is how you have to navigate these unwritten rules of bluegrass in order to make a living. How does this differ from when you were starting out in Chicago in the ‘70s?

GC: Well, it was a completely different world, because in the ‘70s there was a huge club scene. A good example was Lincoln Ave at Fullerton. You could walk north on Lincoln and within not even a mile, there were probably ten clubs, so you could go door to door, literally. There were folk clubs like Orphans, Holstein’s, and Somebody Else’s Troubles. And across the street was Irish Eyes which had Irish music, and then next to that was the blues club Lilly’s which is still there. So, you could park your car, walk less than a mile, and get all kinds of music. One night Orphans might have rock n’ roll, Holstein’s would have progressive, folk, country, or New Grass Revival. Somebody Else’s Troubles would have Fred Holstein and then across the street Irwin Helfer, one of those blues guys who plays the piano, would be at Lilly’s. And we used to play all those clubs. You could pretty much eke out a living because we could play six nights a week. It wouldn’t be much per night, but we could get by.

It wasn’t so competitive. There were guys in some of the rock bands that would come out to hear us and we would hear them. We had the Old Town School of Folk Music, they always brought in great bluegrass, even when it was just a little place on Armitage. They would have Bill Monroe every year, the Osborne Brothers, Jim and Jesse. I used to go on Sunday afternoons at this divey bar on Wilson in Uptown and play music with all these guys from the south. That’s how I met Leon Jackson who’s a famous bluegrass songwriter. He wrote “Love Please Come Home” and a bunch of other songs that Bill Monroe recorded. He gave us songs for our first record. It was really cool—there was a vibrancy to the scene.

HG: What was your repertoire like then?

GC: We used to do a lot of rock n’ roll covers to play these clubs. I just wanted to play the Flatt & Scruggs and J.D. Crowe. But to get people to come to the clubs—I mean, I could play “Amy” by Pure Prairie League standing on my head in a cornfield sneezing from allergies.

BW:That was the “Wagon Wheel” of that era.

GC: So, our musical influences were there, but a lot of it was to get people out to the club. At that time, you had progressive people like New Grass Revival; Bill Monroe was appalled at first but then liked them. Sam Bush is a prime example of somebody who could do his music and make people realize this is just great music, regardless of genre boundaries.

HG: Older folks being appalled at first and then coming around to it—that’s a pattern that plays itself out over and over again through the decades. Did you have different audiences at these clubs that featured different genres?

GC: I think it changed over time. Back then there weren’t clubs in the suburbs, so people would come into Chicago. But the massive numbers of people coming into town was what ended it. The landlords were making a fortune, and they kept raising the rents on the club owners.

But then in maybe the early ‘80s clubs started getting built in the suburbs. People started going there for music. I think that’s when people started being more specific about genres.

BW: At the heart of that Lincoln Ave. explosion people just went there to see music in general and almost club hop a little bit?

GC: Yeah, or they may go there to see a particular group, but they’re not going to stay for all the sets. They’d go to at least one other place.

BW: How much of this change is connected to technology like home VCRs? Did people stop going out to see music in the middle of the ’80s because there was so much more on television and they were able to get their entertainment at home?

GC: Probably for the masses, yes. Thank God are still loads of people who just love to support music of any genre, as well as people who support a certain genre.

HG:Do you think you get fewer casual fans dropping in then?

GC:Yeah, people now buy tickets online to go see a specific band and stream their music. I think where technology helped our music is that you can learn how to play an instrument or how to sing in your living room online. When I was starting I was slowing records down to sixteen and dropping the needle. I’d have to buy two or three copies of the same album because I’d literally wear down the grooves just trying to get those licks.

HG: Fascinating! But it seems like you had a lot of help from other musicians, too.

GC: The musicians in that scene all communicated much like Ben and I do. Everybody used to have the impression that everyone was so competitive. You didn’t want to handle other people invading your market, just like Bill Monroe used to think. But then, like him, you realize that if you help and support each other, it’s much better for everybody.