Home > Articles > The Tradition > Stringbean and His Banjo

Stringbean and His Banjo

Photos Courtesy of Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum

In the summer of 1972, Mark Jones, son of Grandpa Jones, auditioned to perform at the newly-opened Opryland theme park in Nashville, Tennessee. He had practiced his chosen number on the banjo, working out solos high on the neck. Before auditioning, he ran his performance by his father’s best friend, David “Stringbean” Akeman. When Mark finished and asked Stringbean what he thought, the banjo-playing veteran replied, “Little man, you done well. But there ain’t no money past the fifth fret.”

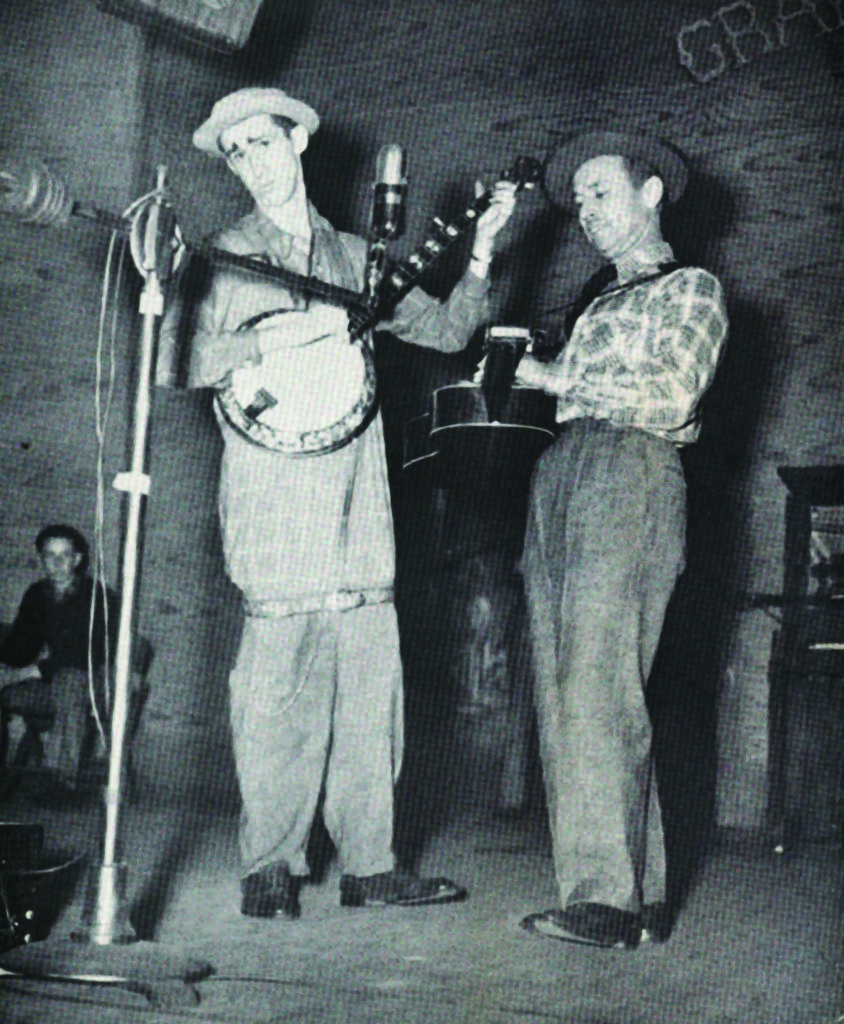

It was a quintessential Stringbean line, full of layers. The first, most obvious layer pointed out the contrast between Stringbean’s clawhammer style of play and the three-finger bluegrass style of Earl Scruggs. Stringbean, who preceded Scruggs as a Blue Grass Boy and was mentored by old-time banjo player Uncle Dave Macon, was taking a friendly swipe at the brilliant, surgically precise but also bloodless, atomic-era style of Scruggs. Where Uncle Dave, Grandpa, and Stringbean entertained with jokes, clever lyrics, banjo-twirling, and vigorous clawhammering, Scruggs stood still, silent, and stone-faced. In his dry-witted way, Stringbean was reminding the young man that his meals came from a father who entertained in the old-time style.

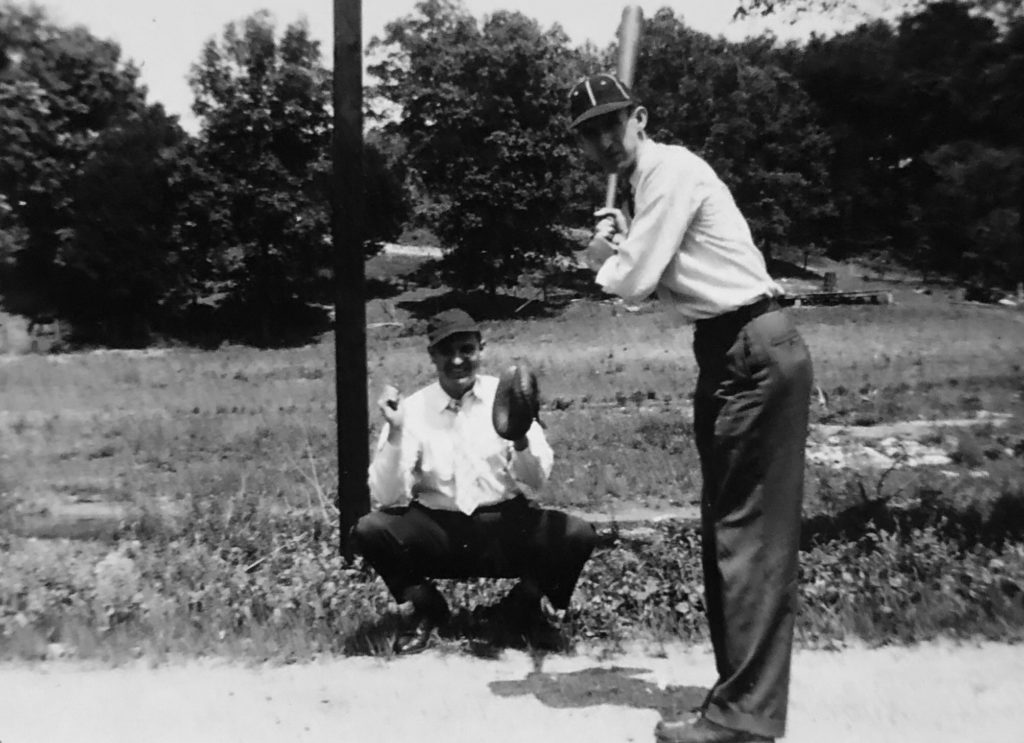

A closer look at Stringbean’s own playing reveals another layer, for his performing actually carried on a subtle dance around that fifth fret. When he was not taking his left hand off the fretboard altogether and making a Babe Ruth-like gesture (the move of a talented baseball player), Stringbean would sometimes slide his hand up to the twelfth fret and tap his fingers rapidly. His dancing fingers did not press the strings at all, and his eyes wandered off listlessly, obvious artifice perhaps meant to burlesque those bluegrass players. Meanwhile, Stringbean routinely emulated Uncle Dave’s antic of gliding his right hand the opposite direction, strumming from the head along the neck toward and perilously close to that fifth fret before he let it dance back down to the head again.

That fifth fret flirt epitomized the comic genius of Stringbean—a masterful, sly irony that managed to be both outrageous and understated at the same time. That blend was completely authentic and unique to David Akeman. He used it in everyday life when he would call someone on the phone and pretend to be the person he was calling. The same contrast characterized his lifestyle of strenuous penny pinching while trading in for a new Cadillac every year—a luxury that served his simplicity since he and his wife, Estelle, simply reported the total miles on that “work vehicle” for tax purposes. His genius expressed itself most fully in the outrageous visual of his costume of long shirt and short pants that any other shy Kentucky boy would never dare to wear in public.

Stringbean expressed his unfathomable nature in a self-penned lyric that he was “baffling the blue-eyed world” in his classic autobiographical song, “Herding Cattle in a Cadillac Coupe de Ville.” It is a great joking song about the paradox of his life as successful Opry star who lived in a tiny house in the country. One of the memorable times he performed that number on television, Earl Scruggs stood to his right, not playing his famous Gibson Mastertone banjo but a guitar. When Stringbean broke into a solo, Scruggs smiled and said something to him. String reacted by smiling also and proclaiming, “Play it, Earl Scruggs.” Scruggs then broke into a full-on grin. Could it be a coincidence that Scruggs spoke just after Stringbean’s ring finger dared to reach from the fifth to the seventh fret?

Stringbean’s unusual relationship with money has been well documented. His coming of age during the Great Depression, not trusting banks, and carrying large sums on his person all were determined to have led to his murder on November 10, 1973, despite the troublesome fact that a huge wad of cash remained on his body when the police arrived the next morning. Well before his murder and long after he had ceased having to worry about money, however, Stringbean was cutting costs in every way he could think of. But not when it came to buying that Cadillac, acquiring a lake home and bass boat, or purchasing and maintaining the fine instrument he played, with its magical fifth fret, as though on that little piece of wire might be tagged the end of a rainbow with a pot of gold.

No one now knows how much Stringbean paid for the Vega No. 9 Tubaphone banjo he acquired around the same time Bill Monroe found his legendary Loar-designed Gibson mandolin. Stringbean also owned a Gibson RB-1 left to him by Uncle Dave, but it was that Vega that really defined the Stringbean character. That banjo was the perfect instrument for Stringbean’s alternating between clawhammering and the two-finger picking style. It was its unique tone ring that allowed that versatility: the tubaphone ring, which has been described by the Deering company as the SUV of tone rings, able to accommodate a range of styles. A strong argument could be made that the distinctive tone ring was the actual part of the instrument that made Stringbean his money, and it was way past the fifth fret. Or way before it, depending on point of view.

A fret is many things: a physical demarcation, a unique kind of wire, a mathematical incarnation, a devilishly difficult thing to install, level, bevel, and dress. It is also arguably unnecessary and can enhance or impair the effects of certain playing techniques. Stringbean claimed his very first banjo (possibly made by himself) had no frets at all. Would that mean the entire fingerboard would bring money? Or none of it? Not to make too much of a single joke, but that joke so powerfully expresses the heart of David Akeman/Stringbean, and the banjo is so closely connected with him. What has been said of Pete Seeger—another lanky player of a Vega Tubaphone—could apply to Stringbean, that he literally looked like a banjo.

Since Stringbean’s death, so much of the writing on him has been about the murder and relatively little about the man himself. With 2023 marking the 50th anniversary of his death, the murder story will likely be rehashed. But Stringbean’s life and career as a singer, banjo player, and comic is just as significant as the grizzly story of his murder. When I began working on my book, Stringbean: The Life and Murder of a Country Music Legend, which is scheduled to be published by the University of Illinois Press in April 2023, I had no idea of the journey before me. I had known about him since I was a child and thought his story would be relatively easy to tell. It turned out to be the biggest writing challenge of my life because it required figuring out how to turn two very different stories—Stringbean’s life story and the true crime story of an investigation and murder trial—into a single, coherent, meaningful narrative. I soon discovered that each story could stand on its own distinctly and separately.

Stringbean’s career formed a bridge in the country music industry from its earliest days into the television era and the development of Outlaw Country. While Scruggs’s style is rightly seen as crystalizing a recognizable bluegrass sound, Stringbean’s banjo playing marked a vital step toward establishing that sound. Stringbean was unable to attend the 1965 Labor Day Fincastle, Virginia, event that included “The Story of Bluegrass Music,” which reminded attendees of Bill Monroe’s being the genre’s architect. As Carlton Haney took the audience through the development of bluegrass, he explained Stringbean’s contribution. Then the band broke into “Rocky Road Blues” because Stringbean had played on the 1945 recording of it. The banjo player that day, Lamar Grier, played Scruggs style, but that event nevertheless helped bring Stringbean to the attention of the bluegrass world where he had been to some degree overlooked.

Overlooking appeared in various ways throughout Stringbean’s career. When David Guard, of the Kingston Trio, played a Vega, he was emulating not Stringbean but the aforementioned Seeger. Seeger in many ways resembled Stringbean, the two sharing plenty of the same repertoire. But Stringbean was a little too much at one with the hillbilly Opry audience to appeal to the sophisticated folk audience at first. Stringbean later played at universities and folk festivals, but he always brought with him a gamey blend of the Appalachian wilds mixed with country music industry commercialism. Yet, even when Stringbean joined the Hee Haw cast as a foundational member, the producers were not quite sure what to do with him. Lulu Roman took one look at his over-long torso and over-short legs and could not decide if he was real or another of her LSD hallucinations. “What is that?” she thought. His becoming the scare-crow in the cornfield was brilliant, but it was Stringbean himself who suggested that he read a letter from home that he kept next to his heart, heart, heart.

Where Stringbean was never overlooked was at the Grand Ole Opry, where he remained a regular for over three decades. The energy of his showmanship continuously tickled audiences and fellow Opry cast members alike, and he inspired the adoration of younger stars such as Porter Wagoner, Dell Reeves, and fellow Kentuckian, Loretta Lynn. Stringbean never emerged as a major recording artist, but Opry fans regularly bought his Starday long-playing albums in the 1960s. Had he not been so brutally murdered, he would surely be remembered solely as one of the Opry legends along with Grandpa, Minnie Pearl, and Roy Acuff, as well as a foundational bluegrass figure.

But he was murdered, and that story holds even more riveting twists and turns than are typically related. My research into the murder investigation and trial included reading over 3,000 pages of court records, every single issue of Nashville’s Tennesseean, and most of the issues of the Nashville Banner from November 11, 1973, through December 1974. Standard journalistic comments that the crime devastated Nashville and the country music industry are all true. And the details of the murder most definitely pointed to Doug and John Brown and their family. But the particulars of the investigation are far murkier than are commonly remembered, and the trial proceeded in a series of events that raise as many questions as they answer. In the end, the jury members went on record saying they did not know what half the real truth was but that they were sure Doug and John had been at the scene of the crime.

The jury’s misgivings resulted from the fact that the entire case was built around a “confession” Doug gave to a Banner reporter of questionable ethics for the purpose of pinning the crime on John. Arnold Peebles, John’s attorney, raised serious doubts about the nature of the evidence in the case. Peebles believed another member of the Brown family to have been responsible for the murders. But for a shocking reason with large repercussions, Peebles ended up providing what was surely one of the weakest defenses in the city’s history. Those hapless jurors waded through a morass of information filled with dubious shadows and pressured by a societal demand for punishment and retribution.

During the next four decades, tremendous changes took place. Those changes manifest in the ways the newspapers changed over that time. The Banner folded, but The Tennesseean continued, its lay-out changing, article-title styles altering, and finally the very form of dissemination itself transitioning from print-only to the hybrid of print and online. Over the course of that time, as more and more of Stringbean’s friends passed away, Stringbean morphed in the public imagination into even more of a sacrificial lamb than he was in 1973. By 2014, Doug had died in Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary (the fictional Hannibal Lecter’s would-be site of incarceration) and John claimed to have been redeemed by the blood of the Lamb, supported by the minister of the Cornerstone Church, who had himself done time for murder before reforming. The story had transformed from one of punishment spectacle to societal redemption, and John Brown was paroled.

The terrible moment in time that makes the lynchpin connecting the life story and the true crime story was, of course, the awful murder of two innocent people. Yet, in so many ways that moment had little to do with either those people or the events to follow. There is no evidence that Stringbean did anything to bring death upon himself other than keeping cash in his home and on his person. The spectacle of the investigation and trial had little to do with the Akemans and their lives and a great deal to do with the drama of the investigators, attorneys, and accused. It is, in a sense, easy to forget about Stringbean altogether in the true crime story. And yet it is also impossible.

I have come to realize that the murder itself is a fifth fret. You can read Stringbean’s life up to it or read through the parole, trial, and investigation back to it. But the moment itself cannot be narrated with full certainty. And that adds yet another layer, tragical and vivid. For Stringbean finally is comic and serious, visible and invisible, and completely and irrevocably commensurate with the instrument that articulated himself. He was “Stringbean and His Banjo,” as his own lyrics told of himself:

I am a banjo picker right out of the South.

And I come from there in time of the drought.

And I travel fast and I travel slow.

But I never quit a-pickin on the old banjo.

Of the many photographs taken in connection with Stringbean’s death, two particularly stand out. One is of his costume, recovered from a pond, laid out on pavement, the Stringbean character deflated like a blow-up outdoor holiday decoration during daytime. The other photo features Pete “Bashful Brother Oswald” Kirby, Roy Acuff, and Lieutenant Thomas Cathey putting that Vega No. 9 away in its case to carry it to the police station the day after the murder while its owner’s body underwent an autopsy. The two images seem imprints of something incomplete, unresolved. The thing that animates them has departed, leaving only its outline. That departed thing, in the end, does not explain. But it is knowable and endearing even as it is mysterious and wry. It is the special thing that is Stringbean.