Home > Articles > The Archives > Smilin’ Jim Eanes

Smilin’ Jim Eanes

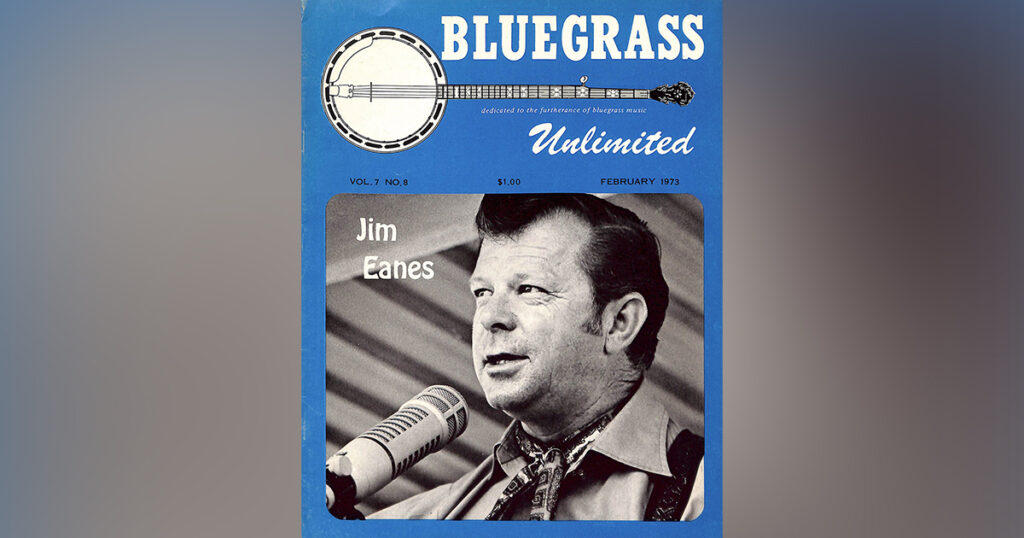

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1973, Volume 7, Number 8

It isn’t Smilin’Jim at all but actually Homer Robert, Jr. son of Bob Eanes a renowned old-time banjo picker from the small southwestern Virginia town of Mountain Valley. Mountain Valley is about fifteen miles from Martinsville in the heart of a circle of approximately 150 miles and covering Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia. From this imaginary circle have come more traditional musicians than any other section of the country. Virtually the complete hierarchy of bluegrass and old-time music come from the area. The Stanley Brothers, Jim and Jesse, Don Reno, Red Smiley, The Osborne Brothers, Kenny Baker, Doc Watson and Jim Eanes all come from the same general area. Born December 6, 1923 he acquired the nickname “Smilin’Jim” early in his childhood and has been known by this ever since.

His interest in traditional styled music came at an early age from both of his parents. With a handicap to his left hand caused by an early burn, a bit of reverse psychology got Jim started playing the guitar. He picked up the basics from his father. “My daddy played a five string banjo. He did two finger picking. I liked the music but due to the handicap I had with my hand I couldn’t play. Or I should say THEY SAID I COULDN’T PLAY. I was determined to show them that I could do it. That’s where I started. I don’t remember exactly how I burned my hand. I was about six months old and fell out of a high chair and grabbed a hot andiron. My noting fingers are twisted. I started playing with my fingers webbed which was how they grew out after the burn. In 1936 I had an operation to cut the webbing out and they wanted to cut the leaders and said that by doing it I might have two straight fingers. I told them no and to just leave it like it was. Now I can’t do all these fancy chords and all that but it doesn’t bother me that much. I was determined to show everybody that I could learn how to play.”

Jim, like Lester Flatt, Carl Story, Carter Stanley and Charlie Moore among others, plays with thumb and finger pick rather than a straight one. “Actually I started doing that because I played a lot of square dances and you had to play as much rhythm as you could because there wasn’t any PA system. The fiddle player who is playing with me now, Willie Gregory, his daddy played a fiddle and my dad played guitar and I started playing square dances with them on Saturday nights. The kind where you move all the furniture out of the room and about forty or fifty people would come in. We would pass the hat around and make about a quarter each. We would get all the good food you wanted to eat, but we didn’t get paid too much. We played for about an hour and a half without any PA set and I had to get all the volume I could. I found I could get more using a thumb pick.”

In 1939 Jim obtained his first professional job as a member of the late Roy Hall’s Blue Ridge Entertainers. Roy’s style had much in common with the early roots of bluegrass. He recorded for Bluebird and American Record Company (Vocalion, Conqueror, etc.) and used instrumentation and songs which were later to become a part of bluegrass. He was one of the first to use a Dobro as a part of a mountain string band not to mention five string banjo and fiddle. Roy’s fiddler at the time Jim worked for him was Tommy Magness. Magness also was a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, recording some of Bill’s early efforts for Bluebird/RCA. “I was working a local radio station in Martinsville, Virginia and Roy wanted me to come to work with him at WDBJ in Roanoke. Roy played the guitar also. He had Tommy Magness and his (Roy’s) brother Jay Hugh Hall. Jay and I were featured mostly on duets. Gordon Reed was on the bass and Hank Anglin on the banjo. Hank is an insurance salesman now. He was doing that three finger stuff. He (Roy) was on the Bluebird label at that time which was a subsidiary of RCA. He had recorded tunes such as Natural Bridge Blues, Don’t Let You Sweet Love Die, I Wonder Where You Are Tonight and stuff like that. I worked with him until he got killed in a car wreak in 1943.

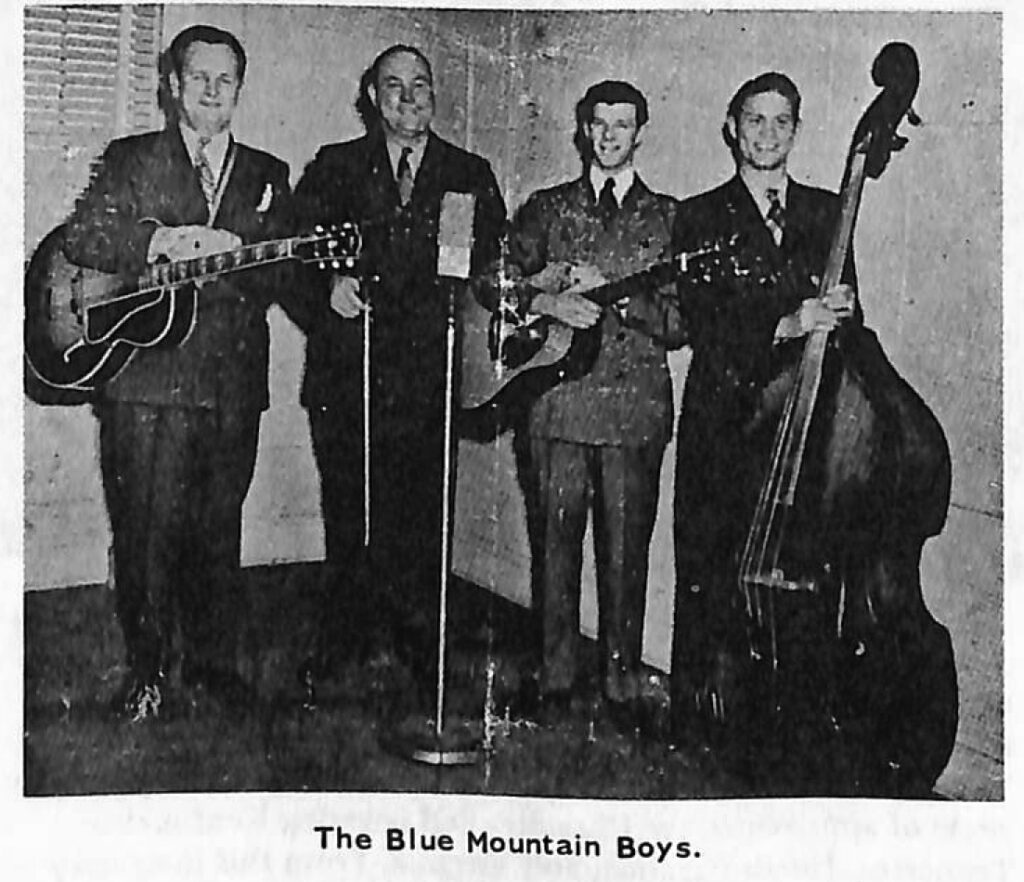

Jim returned to Martinsville and started a local dance with his father again. “We played local dances around Martinsville and they had a big jamboree on Saturday night that they called the Henry County Hoedown. They held it in the National Theater. I was working in a furniture factory too. I started selling insurance in 1945 or ‘46. Joe Johnson, Burk Barbour and Happy Bobbitt came in, the Blue Mountain Boys. We formed a group called Jim and Joe and the Blue Mountain Boys. We worked the local radio station there in Martinsville. We went over to Galax and opened the new station there, WBOB. After that we went to the Tennessee Barn Dance at Knoxville, Tenn. ” Some of the early country artists who were becoming known throughout the nation were on the Barn Dance in Knoxville at the time. “We went to the Tennessee Barn Dance and Midday Merry Go Round in Knoxville. That was on WNOX. We stayed there about nine months. They had Carl Story and the Rambling Mountaineers, they were on the show and Archie Campbell, Molly (O’Day) and Lynn (Davis), The Carlisle Brothers (Cliff and Bill) and Charlie Monroe and the Kentucky Pardners. This was in 1947. During his stay with the Blue Mountain Boys they went to New York and recorded for the National Record Co.

“We did thirty-two sides with Mr. Green. This was in 1947 while we were working at Knoxville. They (National) only released one record from those sessions.” Jim also collaborated with songwriter Arthur Smith in creation of four songs which became big hits in the later years. The titles being, Wedding Bells, I Overlooked An Orchid, Next Sunday Darling Is My Birthday and Missing In Action. The latter song was to become Jim’s biggest seller later in his career. Joe Johnson and Jim sang “Wedding Bells” for a number of months over the Barn Dance but had neglected it since there was no response to the song. According to Jim, Claude Boone, who was working for Carl Story at the time offered to buy the song and Jim and Arthur sold it to him for a few dollars. At the time it was not at all uncommon for a writer to sell his composition completely. Jim and Arthur Smith were also instrumental in introducing the song Wedding Bells to Hank Williams who made it one of his early hits.

Near the end of the 1947 Jim left the Blue Mountain Boys and returned to the Martinsville area. “In January of 1948, Lester and Earl left Bill Monroe. Lester and Earl and Cedric (Rainwater), whose real name was Howard Watts, called me from Shelby, North Carolina, and I went and picked them up. We all came back to Martinsville and decided to start a program in Danville over WDVA. This was the original Foggy Mountain Boys. About two weeks later Bill (Monroe) sent me a telegram and I went to work with him.”

Bill Monroe had heard Jim while playing shows around Jim’s home area of Martinsville and Danville, Virginia. “I guested on some of his shows before. He would come through this part of Virginia and North Carolina. When he went to the Opry he left from Charlotte, North Carolina. Bill and Charlie were working together as the Monroe Brothers and Bill and the Blue Grass Boys; after they were formed, would play Martinsville, Roanoke, Danville, Virginia and on down through Reidsville and Greensboro, North Carolina. I had been a guest on a number of shows with them before. The band was Benny Martin and Don Reno, who went to work with Bill the same time I did. Joel Price was on bass and the boy on Hee Haw, he’s from down around Norfolk, Virginia . . .Jackie Phelps. Jackie was playing guitar and steel at that time.”

Jim worked for approximately nine months as a member of The Blue Grass Boys. “I used to sing Baby Blue Eyes (one of Jim’s most famous compositions). I featured that and of course we would do “Will You Be Loving Another Man” and other duets like that. I couldn’t sing this B or B flat which was way up there – my voice was too low. But when it went into a lower key I could get it all right. The experience that I had with him (Monroe) helped me a lot. He’s a good man to work for.”

Jim returned again to Martinsville and managed a record shop in the town. Early in the spring of 1949 Capitol records was having a big talent contest in Charlotte, North Carolina with a recording contract as the prize. Jim was persuaded to enter the contest and walked off with one of the prize recording contracts. “This friend of mine advised me to go down there and enter. Tex Ritter and Lee Gillette were running the thing. Lee was the A & R (Artists and Repertoire) man with Capitol at that time. Tommy Faile and I were the winners of the contest. There were 534 musicians and Tommy and I were the ones who got the contracts. When I got there and saw all those musicians I thought that I just didn’t have a chance because I didn’t have anybody (to back me) but myself. I had sat around for about four or five hours and didn’t think I was going to get on. They had handed out numbers. They called a number and I was backstage and I thought they had called my number and I went out. Tex Ritter said, “Are you number so and so?” And I said, “No, I’m number so and so.” He said, “Well since you’re out here you’d might as well . . . where’s your band?” I said, “I don’t have a band.” I sang “Baby Blue Eyes,” left the stage, got in my car and came on back home and they called me that night. They said, “You won the contest, can you come back down tonight?” I said “No.” It was one o’clock. But I said, “I’ll be back down in the morning” We went into the studio at one of the radio stations down there and the network kept feeding in on the session. So we went down to the distributor’s place and that was where we recorded. At that time he was recording me and Tommy Faile. Tommy had the Hired Hands with Snuffy Jenkins and Homer Sherrill as his group. Tex (Ritter) recorded Careless Hands and Old Shorty at the same time and I did Baby Blue Eyes and You’d Better Wake Up. I used Snuffy and Pappy (Sherrill) to back me on my record.”

Upon the success of winning the record contract with Capitol, Jim returned to playing music. “I went out to Hollywood, California for about six months. Then I went into Detroit and Chicago, and worked the clubs. I returned to Knoxville and stayed there until February of 1951. Clyde Moody has a band called the Carolina Woodchoppers and he was working at WBTM in Danville, Virginia then. Clyde was offered a spot on the Louisiana Hayride and he wanted me to come down and take his place at Danville. Of course, he painted a very rosy picture and it turned out not to be anywhere near what I thought it would be. When I went there I was supposed to get a certain amount of talent fees from the radio station and fees from the Barn Dance. There was about ninety people on Saturday night and we got a S3.00 sustaining fee.

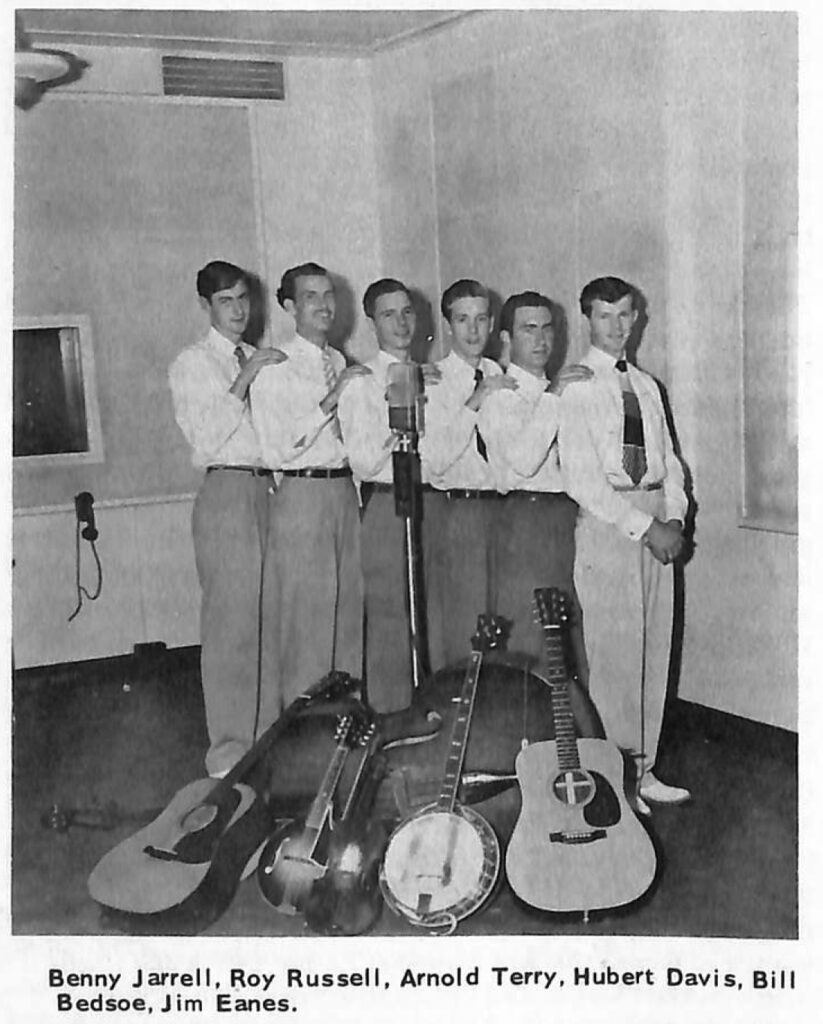

Since I had quit a good job with Lowell Blanchard over at the (Tennessee) Barn Dance, I figured since I was in Danville, I’d might as well make the best of it. For the first two months I did a fifteen minute program by myself. After I built the Barn Dance in Danville up to three or four hundred people, I knew I had to get a group in there. That’s when I formed the Shenandoah Valley Boys. I registered the name in March of 1951. Somebody told me about a little banjo picker called Hubert Davis from Shelby, North Carolina who picked like Earl (Scruggs). I went down to Shelby, North Carolina to talk to Hubert. I asked him if he wanted a job and he said he would go to work for me if I would hire his brother, Pee Wee. So that was how I hired Pee Wee and Hubert. Now I had a fiddle player; Dee Stone, who was working some on the Barn Dance that I was going to keep but when Hubert wanted Pee Wee to be with him I hired both of them. I asked them about a tenor boy. Someone who could play bass or guitar and sing tenor.

They knew this boy who lived over in Rock Hill, South Carolina who played guitar and could sing tenor. His name was Nealy Gilfillian. We went over and hired him. Latter on we hired Benny Jarrell to play bass and he also played fiddle with us for a while. I started them out at S35.00 a week which was good money back then. I brought them all back to Danville and started doing a live program. The Barn Dance kept growing and growing. We were having about a thousand people on a Saturday night. My radio program went from fifteen to fifty-five minutes live every day. I picked up a boy from over around Hillsville (Virginia), Bill Bedsoe. He played mandolin and was real good. I got Arnold Terry to come to work with us about that time too.”

Using this first band Jim recorded his first session since the Capitol records for a small company based in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, Blue Ridge Records. “It was Noah Adams and his daughter Drusilla. They called me in Danville and asked me if I wanted to record. I told them I’d be glad to. We set the time to go over to WPAQ in Mount Airy, North Carolina. I wanted to record this war song that Arthur Smith and I had written while I was in Knoxville called Missing In Action.

Arthur (Smith) came all the way to Danville from Knoxville. This guy who had brought Arthur from Knoxville wanted a third of the song for driving him down. I remember we sat at my cousin’s place and worked out Missing In Action-finished it up. He (Arthur) had wrote a verse and a chorus and I helped him finish up the song and recorded it. “When the company released the record it was an immediate success.” They (Blue Ridge) had one company, Empire records, pressing that one record and with all the back orders they said that it had sold almost 400,000 records. Everybody was doing the song. Ernest Tubb, Jimmy Osborne and others. That was the springboard to the Decca contract.”

Jim previously had another release which also did well. It was recorded in the second session for Blue Ridge but was leased to another pioneer company in country music and bluegrass, Rich-R-Tone. The song was a version of one of Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith’s old tunes called I Took Her by Her Little Brown Hand. It told quite a unique story of an interracial romance and, for it’s day and time the early 1950’s, was not the exact record to be expected from a traditional country performer. Jim featured the number on all his appearances and there was little if any adverse reaction to its message. “I just sung it like I got the words. It was real good for me. I recorded it for Decca and they took the banjo out of it and put the steel in it and I think it hurt the song. I told Paul (Cohen), who was A & R man for Decca at the time that it was strictly a banjo type song.” Decca also had Jim drop the direct reference to the racial aspect of the song making the interracial aspect a bit less obvious. “I never had anybody question me at all about the song until I cut it for Decca.”

About that time Jim added another musician to his group who remained with Jim for many years — fiddler Roy Russell. “Benny Jarrell had told me about a boy who was working down the street with Glenn Thompson on WDVM. I told Benny to see if he wanted a job. That was how Roy came to work with me.”

With both “I Took Her By Her Little Brown Hand” and “Missing in Action” as significant hits Jim was offered a number of contracts by major record labels. “Troy Martin was working for Southern Music and he called me. I knew Troy before. I had three contracts offered, Columbia, RCA and Decca. Paul Cohen was working for Decca and Owen Bradley was his assistant. I listened to Troy. He told me to go with Decca. We went in and I picked up this song from Autry Inman, “I Cried Again.” It was the “B” side of the first record. I had cut a follow up to Missing in Action for Decca as the first release. It was called They Locked God Outside The Iron Curtain. I Cried Again was on the back side of that. Well the war song didn’t do anything but I Cried Again took off. Decca pulled the release back, held it two weeks and then released it again. They used I Cried Again but backed it with Between The Lines and not the war song. If they had left it alone I think it really would have done something. Things got confused since the song was first out and available and then called back and put out again.”

Jim and the band were quite popular around the area of Danville and working shows almost every night. “I had so many shows at the time I couldn’t play them all. They would call in. We would never have to go looking for a show. We worked about every schoolhouse and ball around there.”

Jim stayed on Decca for almost four years and had quite a few releases that did well for him. Wiggle Worm Wiggle, one of Jim’s compositions, and I Cried Again and Little Brown Hand. Jim had tried to cut Wiggle Worm Wiggle ever since he went with Decca but the company always thought it not commercial enough. “I would put that song first on the list every time and they would reject it. Finally I got a chance to do it and Grady Martin put a hot guitar kick-off on it and it did real good for me. It was straight bluegrass.”

Country music was to suffer greatly from the appearance of Elvis Presley and the rock and roll acts during the mid-fifties and Jim is very direct in his appraisal of Elvis’ impact on traditional music. “Well Elvis came along and he put us out of business. I went into radio then.”

Jim has worked as a disc jockey and radio announcer for a number of years and would play music in addition to his duties as an announcer. “This friend of mine who I first had a job with in ‘39 built a radio station in South Hill (Virginia) WJWS and he offered me a job. They had brought in UHF television and they wanted me to do a kiddies show. I was to play guitar and sing the songs for the kids. I didn’t see any future in that so I went to work for the radio station in South Hill. This guy who owned the station told me to come down and he would show me everything that I need to know. I had never worked at a (control) board before. I went to work on Monday morning and he said, “There it is . . . find it! If you have to find it you won’t forget it.” You can imagine what it sounded like. I stayed there for eight months and he built a station in Martinsville, WHEE. I moved back to Martinsville.”

Jim had not recorded in some time and Starday records was pushing bluegrass music quite heavily. “Don Pierce (former head of Starday) called me and wanted me to come to Nashville to record. I told him that I had good studios where I was.

I recorded the first session for Starday at WPTF in Raleigh, North Carolina and then all the rest were cut at WHEE in Martinsville.”

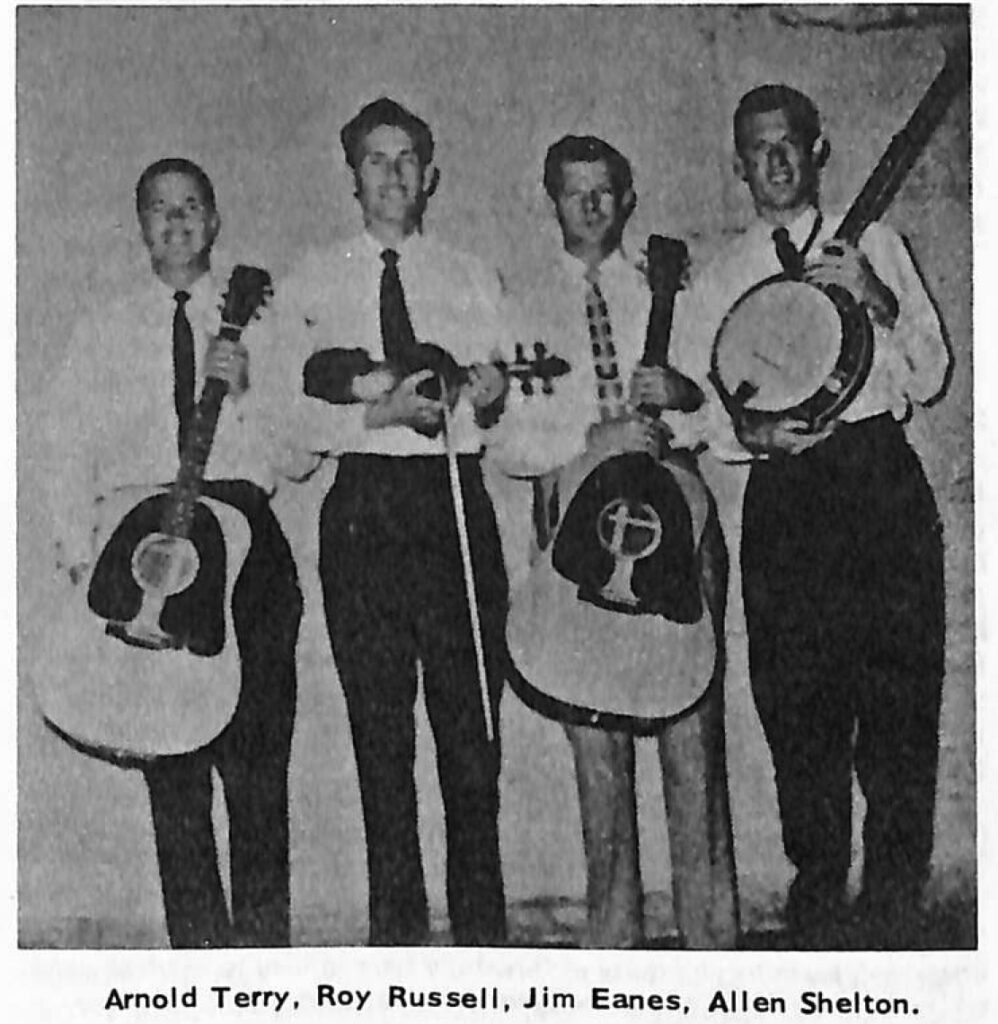

Jim’s band during most of his tenure with Starday consisted of Jim on guitar, Arnold Terry on guitar, Roy Russell playing fiddle and Allen Shelton on banjo. Allen had come to work with Jim in 1952 or 1953. “He (Allen) was a fascinating musician. The most interesting banjo picker I ever heard. I advertised on the radio that I was looking for a banjo player.

“Allen and his Daddy came up one Saturday. He had a roll and it was backward. I heard him play one tune, Cumberland Gap and he could really play it. I hired him on the strength of that one tune. When he came to work with me I found out that he could only play that one tune. But he would play all the time. He would pick in the car, in the room, at the station, during breaks, everywhere. The boys would get behind my back and start playing Lady of Spain and the World is Waiting for the Sunrise or Whispering and I was still playing that three-chord stuff. He left me and went to work for Mac (Wiseman) and then went to work with Hack Johnson. That was when he recorded Home Sweet Home, while he was with Hack. In fact, I recorded a cover of that song with Hubert Davis on banjo for Decca. We called it There’s No Place Like Home.”

Allen Shelton was working with Hack Johnson at WPTF in Raleigh, North Carolina as a member of Hack’s band the Farm Hands. Hack had former members of Jim’s band Allen Shelton and Roy Russell with him in addition to guitarist Curly Howard and bassist Joe Phillips. Hack decided to quit music and the band remained together as the Farm Hands playing at WPTF in Raleigh, North Carolina and also WRVA Richmond, Virginia as members of the Old Dominion Barn Dance. After losing the job with WPTF in Raleigh Allen Shelton and Roy Russell returned to Martinsville to again join with Jim as members of the Shenandoah Valley Boys.

“I was disc-jockeying and working a bam dance at the local VFW hall and playing a live program from 1 to 1:30 every day on the radio station plus show dates. I was working seven days a week. I got up at 4:30 every morning and did my record show and then with the band we did the live program in the afternoon. We were playing on Friday nights for the local ladies auxiliary and then on Saturday nights for the VFW”.

When the group’s first Starday record Your Old Standby and Don’t Stop Now was recorded the pedal steel guitar was the rage in country music and Allen Shelton came up with a way of duplicating the pedal steel sound with his banjo. “Well I wanted to do uptown bluegrass. Everybody was doing the same basic stuff . . . copying (Bill) Monroe. I wanted a different sound. Allen put a handle on his banjo like an electric guitar and tuned it so he could bar it with his finger and we worked up the arrangements using that.” The arrangement was similar to the action derived from the use of a Bigsby tailpiece on an electric guitar plus combining the sound obtained by using the tuners. “He would just push it with his wrist and it would change the tone.”

Jim was instrumental in recording a left-field hit record which appeared on Starday in the late fifties, Pinball Machine. Though the recording artist was Lonnie Irving, the band was Jim’s. “Lonnie Irving had this fellow who played electric guitar and we would use him (the electric guitarist) sometime. Lonnie was a truck driver, he’s dead now, and he used my band on the cut. It was Roy Russell on fiddle, Allen Shelton on banjo, Arnold Terry on bass, the electric guitar player, Lonnie and myself. We cut that at WHEE. Actually it was released on the Irving label and he (Lonnie) bought the first five or six thousand copies. He was a truck driver and sold them on the road like mad. Don Pierce of Starday called me and wanted the master and he worked out a deal with Lonnie and the record was re-released on the Starday label.”

During his stay with Starday Jim cut a number of songs using various mixtures of bluegrass and country music backing. “I was trying to combine bluegrass and country. Something different.”

He also left playing the VFW hall in Martinsville and started a barn dance type of show again. “Another fellow and I built a place called Rockwood Park. He was a building contractor. We worked it for about five and a half months. We would have over a thousand people in that place every Saturday night. I quit the station in Martinsville and went to Danville and went to work for a rock and roll station down there. In 1962 I went to Roanoke and worked on WHYE there. In 1966 I went to WKBY Chatham, Virginia and then on to a station in Stuart and then back to Chatham and from there started working on the Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia. I was working as a solo on the Jamboree and Red Smiley and the Cut-Ups were also working on the show. Since we were both around the same area of Virginia I would ride up to the show with them and they would back me too. When Red decided to retire I went to work with the band. Tater Tate, Herschel Sizemore, John Palmer, and Billy Edwards. We combined the two names, Shenandoah Valley Boys and the Blue Grass Cut-Ups and that was how we got the Shenandoah Valley Cut-Ups. We worked together for about a year.”

Working as a capable M-C and show coordinator for a number of festivals over the past few seasons Jim has started to re-organize the Shenandoah Valley Boys. “I hired a banjo player and a fiddle player. I’m looking for somebody who can play Spanish Dobro. I want a Spanish Dobro, fiddle and banjo. I feel the way those guys in Nashville who play Spanish Dobro play it to work in bluegrass. I’m not knocking the square neck Dobro players, I love ‘em. I still feel like if you can take a Spanish Dobro and put it in with bluegrass it can work. I also want to get back to the trio and duet stuff that I used to have.” The mark of a true professional musician, Jim still strives to improve the sound and style of bluegrass music that have carried the exclusive stamp of Smilin’Jim Eanes.