Home > Articles > The Archives > Rudy Lyle—Classic Bluegrass Banjo Man

Rudy Lyle—Classic Bluegrass Banjo Man

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 1985, Volume 19, Number 10

In any conversation about the great musicians in the formative years of bluegrass music one name always comes up, Rudy Lyle. Rudy played the banjo on many of the classic Bill Monroe recordings including “Rawhide,” “On & On,” “Sugar Coated Love,” and probably his most noted performance on “White House Blues.”

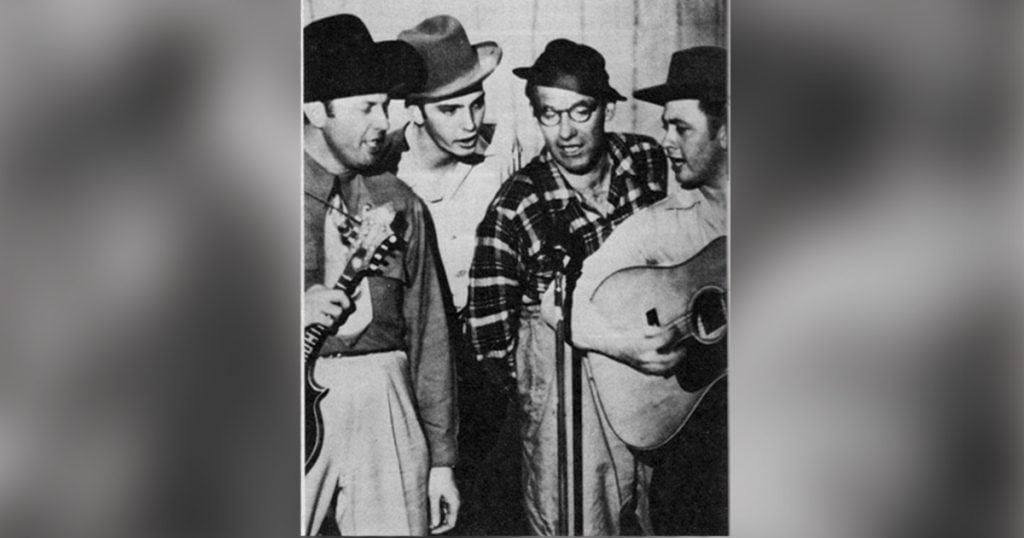

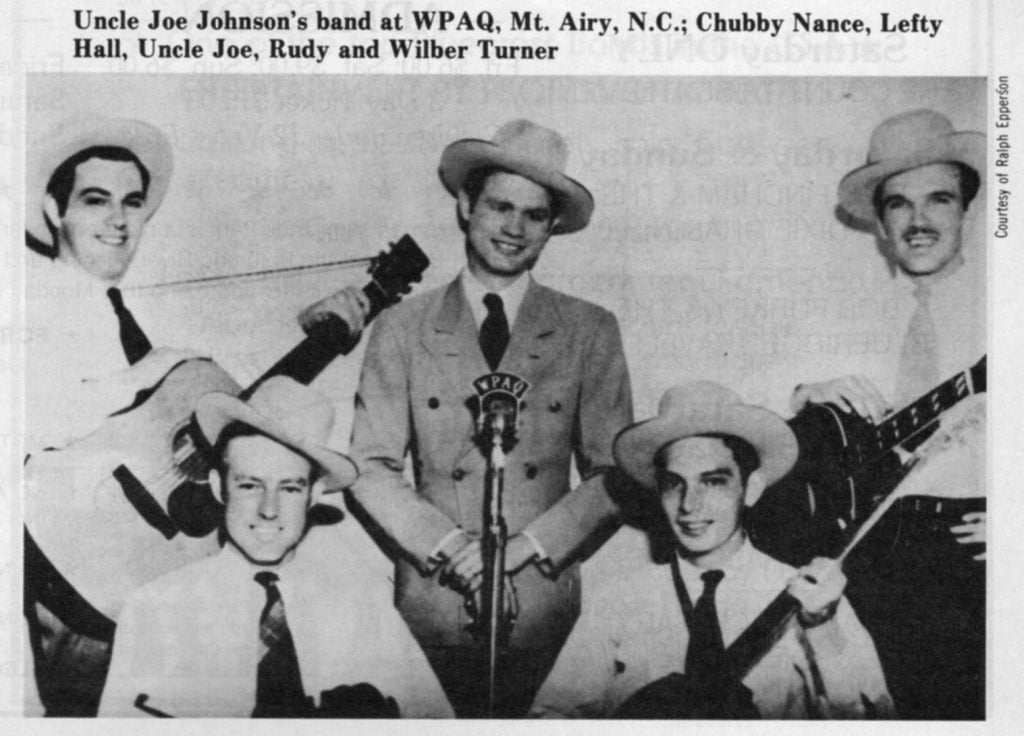

Rudy grew up on the Black Water River near Rocky Mount, Virginia. He lived with his grandfather Lomax Blankenship who was a noted local fiddler. At the age of 9 he began to learn to play the five-string banjo. “Lawrence Wright, he lives close to Rocky Mount. He was the first man I heard play rolls and I picked it up from him, I also learned a lot from Paul Jefferson,” Rudy recalled. In a few years Rudy met two boys from Rocky Mount that played music and began picking with them on WPAQ radio in Mt. Airy, North Carolina. “We had Wilber Turner on guitar and Lefty Hall on the fiddle. They told my granddad that they would take care of me and they talked him in to letting me go with them.” During the time they worked at WPAQ they worked with Uncle Joe Johnson and Pretty Little Blue-eyed Odessa. The band included Uncle Joe on the Dobro, Wilber Turner on the guitar, Lefty Hall on the fiddle. Pretty Little Blue-eyed Odessa singing and Rudy on banjo. It was during this time that Rudy first met Bill Monroe. “I was in Mt. Airy working with Uncle Joe. Bill came through there with a show at the high school. It was on a Friday night that we weren’t working so we all were there. We had announced on our radio program that he was going to be there with his show. At that time Bill’s band had just broken up. Don Reno had just left. He didn’t have too many people working with him. He had two boys called the Kentucky Twins and another fellow named Bill Myrick but didn’t have a banjo player so I tuned up and went out there with him. That’s where we got together. After the show I told Bill that I’d sure like to work for him and he said that he would like for me to but didn’t want to take me away from Uncle Joe. Bill didn’t want to hire me on the spot. I respect Bill for that.

“About three weeks later we were working a show in Radford, Virginia at the theatre. The manager came back stage and said I had a long distance call. It was Bill. He was in D.C. and asked me if I wanted to come to work. I said yes, I was ready.

“I got into Nashville and I didn’t know anything about the town. I had rode a Greyhound bus in. Back then everyone wanted a car but everyone didn’t have one. We had been using Wilber Turner’s car in Mt. Airy. Cars were kind of scarce. I got into Nashville early Saturday morning. I spent the whole day walking around the block down around the station. The Grand Ole Opry was on the next corner. I didn’t know where to go or what to do. Bill had said to be there Saturday night for the first show; the R.C. Cola Show. I was there in the alley when Bill and all the guys came around the corner. We went in and did the R.C. Cola Show. The first tune I did was ‘Cumberland Gap.’ I think the R.C. Cola Show was network then like the Prince Albert Show, so it was getting out pretty good. Bill told them that he had a brand new banjo player from over in Virginia—Rocky Mount, Virginia. Then he told them what I was going to play. I played, then Grant Turner came in. Boy, it was great, it was something else.

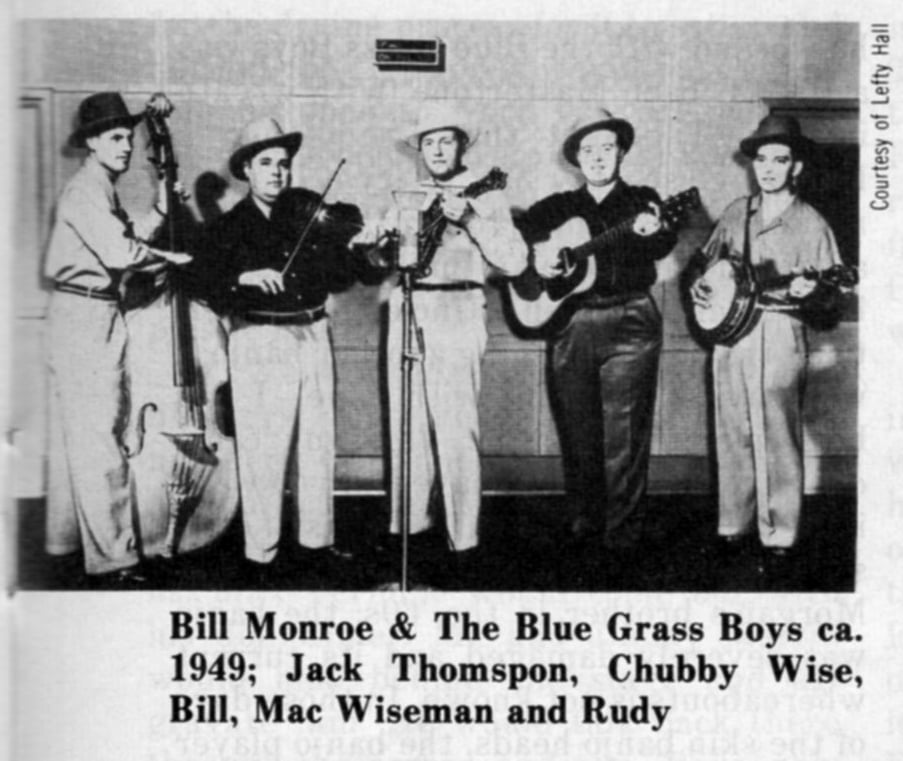

“When I got to Nashville Bill had Chubby Wise, Mac Wiseman, Jack Thompson, me and him (Bill). Joel Price was playing comedy. Jack Thompson was playing bass and he left to work with Lou Childre and Stringbean, to play rhythm guitar for them. Then Joel started playing bass. After Mac left, Jimmy Martin took his place. I brought Jimmy Martin in the back door of the Opry. Jimmy was standing out in the alley one Saturday night. Old Sergeant Edwards, the policeman on the door, had turned him away two or three times. Sergeant Edwards was a big old heavyset mean looking policeman. He could just look at the people trying to get in the back door and they’d run. There was all kinds of people trying to get in that back door.

“I had heard Jimmy play a little bit and I told him to put his guitar back in the case and let’s go inside. We came on through. I told Sergeant Edwards that Bill wanted to try this man out. Bill liked Jimmy’s guitar playing because he played good guitar—solid rhythm. He also liked Jimmy’s singing. Bill could tenor him good. They had a good close duet that was very close to Bill and [Lester] Flatt.”

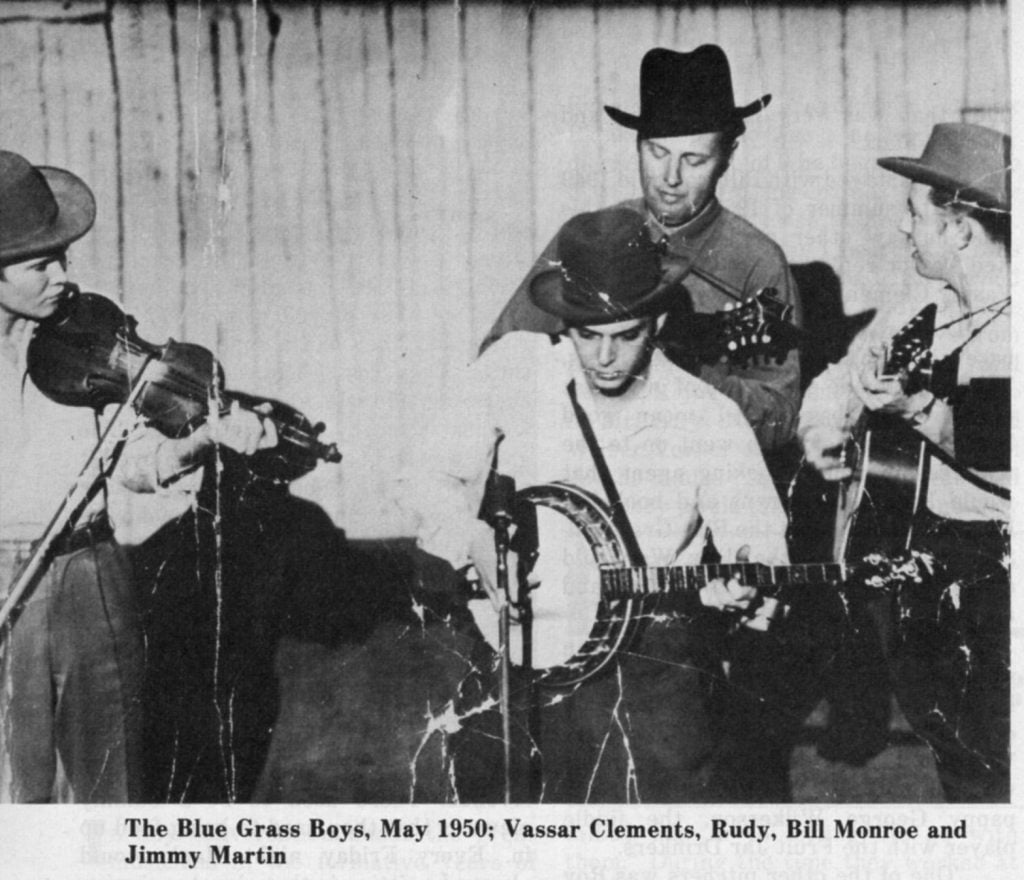

Rudy stayed with Bill from mid 1949 until late summer of 1951. During this time he saw other personnel changes. Red Taylor replaced Chubby Wise then Vassar Clements took Red’s place.

During this time, “Bill had the baseball team, the Blue Grass All-Stars. They were made of a group of guys that played good baseball. I mean good baseball. Some of them went on to the majors. Bill had a booking agent that would book these towns and book the local ball club against the Blue Grass All-Stars ball club plus the show. We would always open it up with the music and after that the game would start.

“Bill would always let Stringbean start out pitching. Then if they got too hot on him and start beating us he would call in his other pitchers like G.W. Wilkerson. They called him Ziggy, he was great. G.W. was the son of Grand- pappy George Wilkerson, the fiddle player with the Fruit Jar Drinkers.

“One of the other pitchers was Roy Pardue from there in Nashville. There was Stringbean, Ziggy and Roy Pardue. They were all great. String was really playing ball. He was a super pitcher but he lacked a little bit of the speed that Ziggy and Roy could put on it. He was a good straight honest pitcher and loved baseball.

“I love baseball too and a lot of times me and Bill would go out to Long Hollow and pitch. He would say, ‘Rudy you’re pretty good but not good enough,’ and I’d answer him back saying, ‘Yes, I know but I’m better than you.’

“Bill would manage [the team]; he didn’t miss anything going on. He watched every little thing. He would work a lot with the catcher and pitchers to make sure they’d change up the pitches. We had a super ball club. We were easy on the other teams when we knew we could win. Sometimes Bill would put Stringbean back in to pitch. The hardest team we ever played was in Des Arc, Arkansas. They had a super good team there. They really had some good pitchers; a good team, and good players but we beat them by a couple of runs. The game was so good, the people enjoyed it so well that we re-booked it right there on the spot for another game to follow it up the next month.”

During this period the Blue Grass boys were in great demand. “We did a lot of package shows—Hank Williams, Hank Snow, Ernest Tubb and Bill Monroe. Those were the big names on the Opry at that time. Hank Williams used to prank with us a lot especially at the Friday Night Frolic up at old WSM on 7th Avenue. There used to be a dummy elevator that they used to bring food up in. Every Friday night Hank would always be sitting in that elevator signing autographs and having his boots shined and talking crazy. He talked to everyone, he never met strangers. He used to always kid Bill about where he got his banjo players.”

During this time the Shenandoah Trio was formed. “The Shenandoah Trio was Joel Price, Red Taylor and me. Bill would use us as a break from himself on the show. We used to do things like the ‘Rag Mop’ song and tunes like that. There were also many songs written during this period. He wrote ‘Uncle Pen’ in the back seat of the car up on the Pennsylvania Turnpike on the way to Rising Sun, Maryland. On that same trip to Maryland, we were traveling in a Hudson Hornet and had a rack on top of the car. We had all our instruments up on the rack. We were going down the Pennsylvania Turnpike and the rack blew off. I mean just blew off. There were all our instruments scattered all over the highway. It broke the neck out of Chubby’s fiddle and skinned up Bill’s mandolin case pretty bad but my banjo wasn’t even out of tune.”

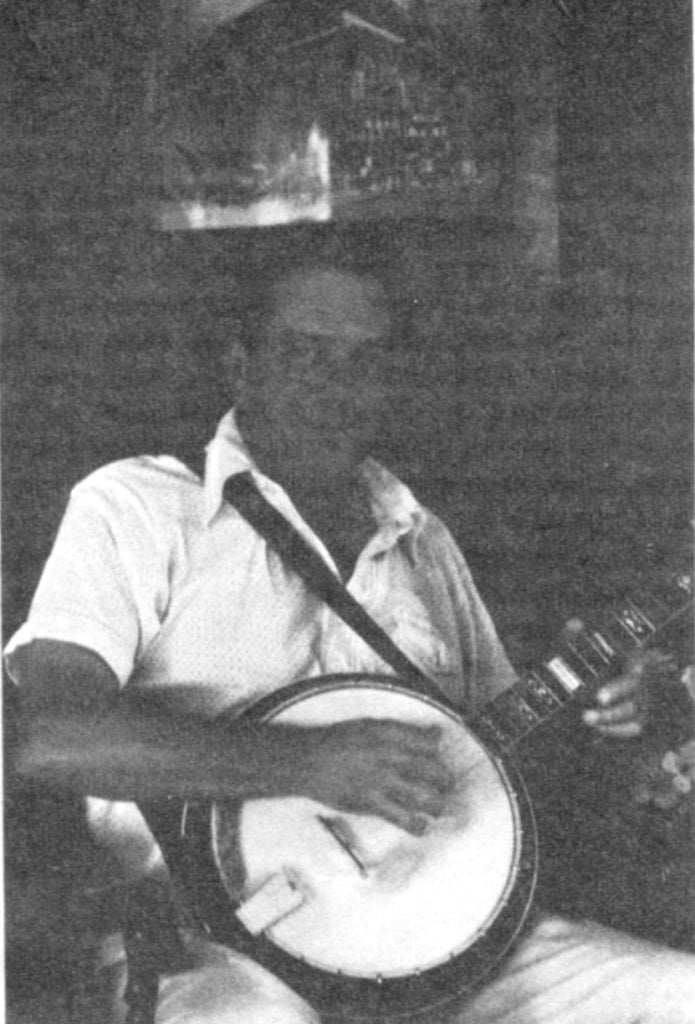

The banjo that Rudy played while he worked with the Blue Grass Boys was a RB-3 Gibson Mastertone (with wreath inlays). “I bought that banjo from a fellow close to Mt. Airy. I can’t remember his name. [Johnny Vipperman, a noted local musician thinks it was probably Early Jarrell.) Uncle Joe advertised that I was needing another banjo; I was having problems with mine—I had been playing a Bacon. This guy came over and said you can have it if you want it for $150.00. I bought it and wasn’t ever sorry.” Rudy traded that banjo to Tom Morgan’s brother in the ’60s; the banjo was severely damaged and its current whereabouts is not known. In those days of the skin banjo heads, the banjo player had to not only play the banjo but be a technician also. The skin heads were very responsive to climatic changes and you would have to change heads whenever one broke.

“We didn’t have room to take two instruments so I’d carry extra heads with me. I kept eight to ten with me all the time in my suitcase. A lot of times I’d get to a job and the head would be busted so I wouldn’t work that job, I’d be busy putting a brand new head on. There was only one way to get them on. They were calfskin heads, I mean real calfskins. You had to soak them in water and get them real loose to even put them on. Then after you’d get them on, you had to wait for the drying process for it to set up and not get too tight or it would bust again. You just had to work with it. I’ve put them on everywhere; in hotel rooms, in the car going to shows. I even put one on backstage at the Opry one night. Banjo players have it good these days with plastic heads.

“We worked a lot of theaters, one nighters; on weekends we’d work matinees. One time we had Johnny Mack Brown, one time Max Terhune, the old Western Cowboys. They’d do shows with us. Max Terhune would come out with his doll Elmer. Me and Jimmy Martin would hide behind the stage and aggravate him. He would talk back there through the screen and say, ‘Boys, now don’t start that stuff.’ I remember once we had been up in Charleston, West Virginia and Bill had this fine race horse he’d bought, trailer and everything. We had that trailer on the back of the car coming around those mountains in West Virginia heading back to Nashville. If I’m not mistaken it was Chubby Wise driving and he said, ‘I think I hear a horse running and he really did. When we got back there we found the whole trailer floor had fell apart and the horse had kept up with the car.

“Once we played a show at Meadows of Dan, Virginia and on the way out we stopped in Wytheville, Virginia. Bill bought this dog from a man there. It was the best dog this man had, a ‘lemon walker’ he called him. We had to be in Poplar Bluff, Missouri the next day so Bill put that dog in the trunk of the car. We had all the instruments in the rack on top. We went all the way to Poplar Bluff, Missouri with that dog in the trunk of the car. We were afraid to open the trunk afraid he’d get out and run. When we got there, there was a big fox chase. The old dog won the chase; he caught the fox. He had rode halfway across the country and still won the race.”

Rudy was no different than many of the other young men when it came to the service. Rudy went into the Army on August 3, 1951 and was replaced in the Blue Grass Boys by the young Sonny Osborne. “If I hadn’t went in the Army I’d have probably stayed with Bill. I’d have been another Oswald.”

During the time Rudy was in the Army he pulled duty in Korea. “On my way back I was in Japan. I was in the PX one day and at the table next to me I kept hearing this guy talking and I kept thinking, I know him. Come to find out it was Dale Potter, he was on his way back home. Dale was one of the finest fiddlers in Nashville.”

After he got out of service he returned to his old job with the Blue Grass Boys. “When I came back from the Army, Flatt & Scruggs were doing the morning Martha White Show at WSM. They were in one studio and we were in the other. Me and Earl was good buddies. He would come by every so often. I remember one Sunday they were working Dunbar Cave in Clarksville and Carter Stanley and me went up there with Earl.”

There had been a lot of changes during the time Rudy was in service. One was an especially bright star on the horizon. Rudy remembers the beginning of another legendary artist. “We done the Phillip Morris Cigarette Show with Elvis. It was the T.D. Kempt circuit out of Charlotte, North Carolina. They called it the ‘Chittlin Circuit.’ It started in Florida and went all the way to Pennsylvania. It was one nighters—theatres, mainly. That was when Elvis was first starting in ’54-’55. We had Carl Smith on the show plus Hank Snow, Bill Monroe, of course Elvis was an added attraction. Tom Parker was bringing him out first and it got to where when Elvis got through doing his show no one else could go on stage. I remember that Hank Snow was trying to follow him one night and there was no way, so Hank just threw up his hands and walked off. They were all hollering, ‘We want Elvis.’ So Tom parker changed it around and put Elvis last.”

After returning from the service, as Rudy put it, “Things weren’t the same.” Many young servicemen probably suffered those same experiences returning home after a period of turbulence such as the Korean conflict. So in 1954 Rudy left the Blue Grass Boys.

“I went up to D.C. and worked for a while. Jimmy Dean had a TV show up there so I went up there. I was a little mixed up. I just got back from Korea. Everything wasn’t the same. My brother, dad and mother had moved up there. There was 3 of us brothers and I have one sister, her name is Patsy. My brother Bobby still works around D.C. playing music five nights a week. He plays the chord-o-vox (accordian). Nelson my other brother doesn’t play much any more, he just plays for fun.

“I was working up there with Jimmy Dean, working package shows with him, Roy Clark was working at the Dixie Pig on Bladensburg Road. I worked some with him. I had started switching back and forth from lead guitar to five-string. Hank Garland is the one that got me to switch. We all used to live together over on Boscobel Street (in Nashville). There was a rooming house over there, Mom Upchurch’s. So I moved in and at that time Hank used to come around there a lot and we always got along real good together. I used to really enjoy to listen to him and watch him play. He was always so accurate, everything was so perfect and in my mind I felt like I could do it too.

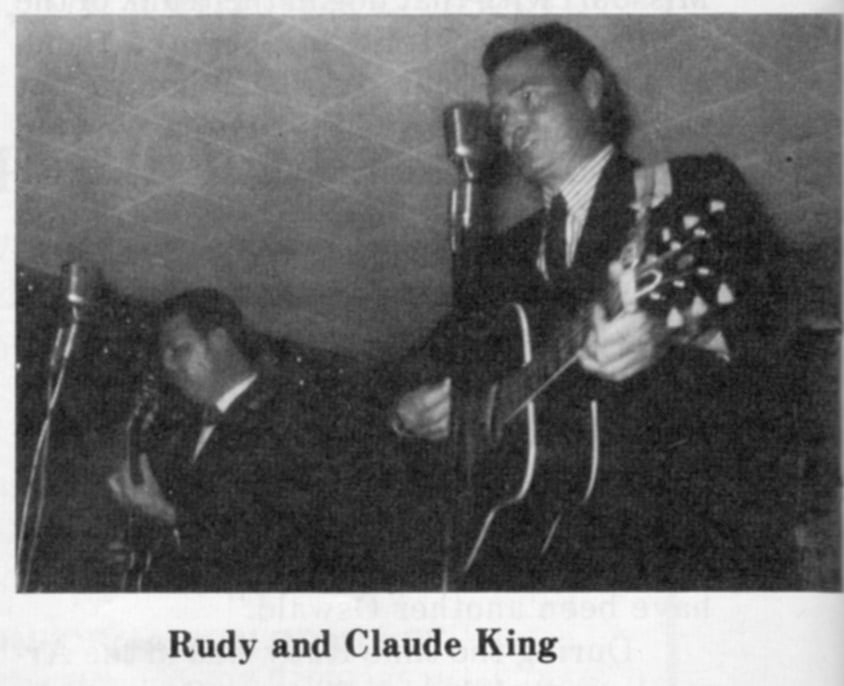

“I worked a while with Claude King, he had the hit song, ‘Wolverton Mountain.’ I worked with Patsy Cline while she was with the Jimmy Dean Show.”

In the late ’50s Rudy moved to the Knoxville area. “I worked for Cas Walker there and with a friend of mine at a car dealership.” It was while selling cars he met his wife, Mary. “I met Mary when I sold her a car, that was in 1963. I was working some with Red Rector and Fred Smith about that time. They had an act equivalent to Homer & Jethro. That’s where Homer & Jethro and Jamup & Honey came from, too.”

After a few years in Knoxville, Mary and Rudy moved outside Nashville where for a time they ran a restaurant and he began working for the Tennessee Department of Corrections in Nashville.

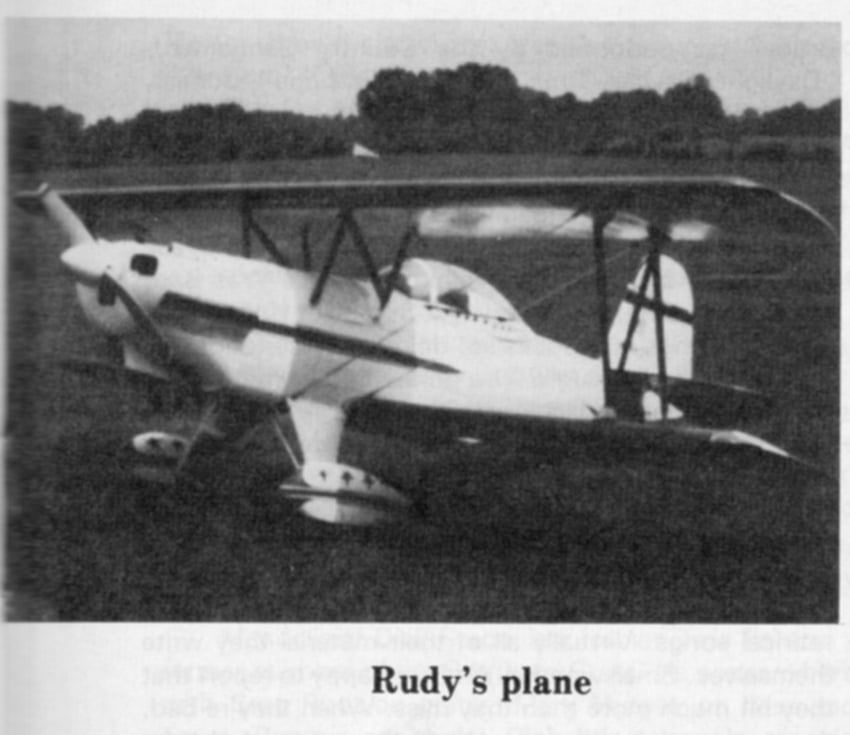

Much of Rudy’s time in recent years had been filled with his hobby of building and flying airplanes. ‘I’ve always liked airplanes. Back when I was living down on Boscobel Street, years ago, me and Randy Hughes, who was with Cowboy Copas when they had their accident, learned to fly together. We would go over to Cornelia Fort Air Park there in Nashville and go flying.

“I bought this airplane, it was all to pieces and put it back together and I restored it. I’ve been everywhere in that plane. I worked on it for five years and I’ve been flying it for ten years. It’s a EAA Sport Biplane, with a 85 Continental engine. It cruises a little over 100 miles an hour. I have a buddy who’s an aircraft engineer who’s got one just like it. We’ll get up early and go out early on weekends and fly—The Dawn Patrol.

“I built a couple of airplanes there in my garage. I helped a doctor here in Franklin build one. I went ahead and got all my ratings then I got my FAA rating to do annual inspections on the aircraft, the A & P License. It’s something I enjoy doing.”

Rudy occasionally got together with some local musicians around his home in Franklin, Tennessee and as Rudy said, “I’ll never retire from my music. I’ll keep on writing songs and playing my music and working on my airplanes.”

All bluegrass musicians owe a great deal to all those musicians like Rudy Lyle who blazed the trail for the music we now know as bluegrass. And Rudy was a trail blazer as Bill Monroe recently said. “There was Earl Scruggs, then Don Reno, they were wonderful banjo players but when Rudy Lyle came in there with me even Earl and Don was listening to Rudy. He could really roll that banjo and he was powerful.”

[Printed in the same issue as the above article]:

Rudy Lyle—March 17, 1930-February 11, 1985

On February 11, 1985 the bluegrass music world was saddened with the loss of one of its beloved family, Rudy Lyle. Rudy grew up in Franklin County, Virginia and began playing banjo at age nine. He began his musical career at WPAQ Radio in Mt. Airy, North Carolina in the late 1940s with Uncle Joe Johnson. He later joined Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys where he left a lasting impression for bluegrass banjo enthusiasts for generations to come thru his recordings with Monroe. His tenure with the Blue Grass Boys was interrupted by a tour of duty in Korea where he was decorated for bravery. After the war he rejoined Monroe then later moved to the Washington, D.C. area where he concentrated on writing songs, playing electric guitar and banjo with various country entertainers such as Jimmy Dean, Patsy Cline, Jim Reeves and Roy Clark. Rudy had not been actively performing for several years but has con tinued to write songs. He wrote over 100 songs one of which being the Star-day release “Brown Eyes Crying Over Blue.”

Services were held in Nashville, Tennessee on Thursday, February 14. Through the efforts of Dutch Hutchings, Benny Martin and John Hartford a special 20-minute tribute of music that was dear to Rudy was arranged for the services and included his recordings of “Rawhide,” “Whitehouse Blues” and the Hank Garland instrumental “Greensleeves.” Rudy was a gentle loving individual that was unaffected by the fame that was due him. Leaders open up new paths while leaving it to the followers to deepen, widen and lengthen the paths. Rudy Lyle was a true leader and although no longer with us his contributions will live as long as anyone listens to this music we call bluegrass.

He is survived by his father, Simpson Lyle, his wife, Mary Wright Lyle, two brothers, Bobby and Nelson Lyle, a sister, Patsy Lyle and a half sister, Janice Chilson.