Home > Articles > The Archives > Rose Maddox—Queen of the West

Rose Maddox—Queen of the West

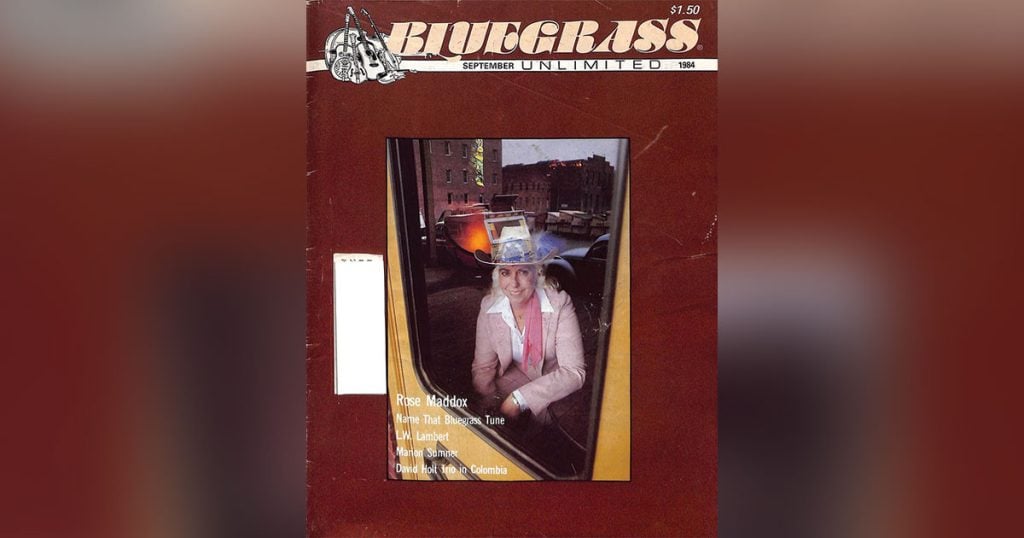

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1984, Volume 19, Number 3

You’re as important in country music today as Roy Acuff was ten years ago.”

Hank Williams was summing up his appreciation for Rose Maddox after a two hour conversation with her in a deserted Los Angeles night club.

A few weeks later they were working together on the Louisiana Hayride when Williams died. It was one of a series of tragedies that have marked the career of the first woman elected to the west coast Country Music Hall of Fame —the deaths in turn of her parents, two of her brothers, and, last year, her only child. Her son Donnie, a fine guitarist and singer who harmonized with his mother both on and off stage, passed away while Rose was playing a rodeo in Reno.

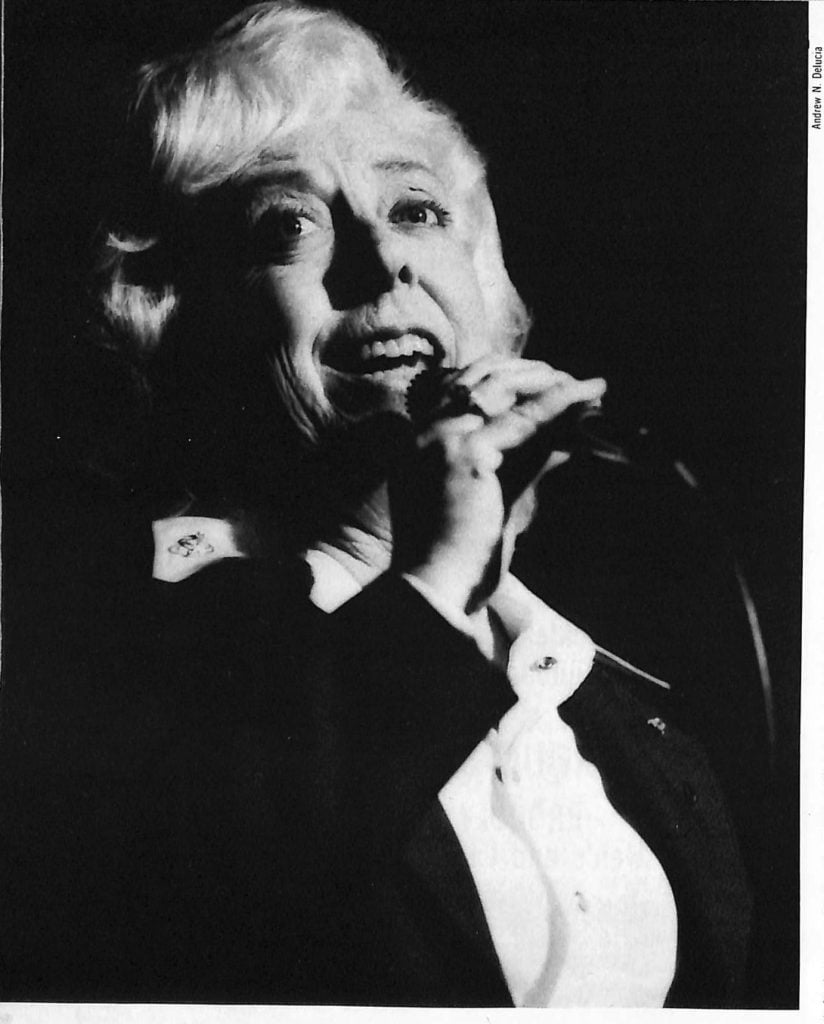

But there have been triumphs as well as tragedies, too, and you would never guess that Rose had suffered all these losses, as well as three severe heart attacks, when she cuts loose with a powerful ballad, old time blues or gospel number. She dislodged a few pine cones at the Grass Valley (California) Bluegrass Festival over this past year’s Labor Day weekend, backed by the legendary harmonica stylist Bill White and his group. It was a smashing wind-up for a heavy summer schedule that saw Rose appearing at clubs, concert halls and festivals and other outdoor events throughout the West. She was on television a couple of times, did innumerable radio interviews and was a featured guest star again on (National Public Radio’s) A Prairie Home Companion.

No fewer than three Maddox albums have been released this year —“Queen of the West” with Merle Haggard and The Strangers and Emmylou Harris (Varrick 010); “Beautiful Bouquet,” a gospel quartet album with the Vern Williams bluegrass band on the Arhoolie label; and a compilation of cuts from old radio broadcasts, also on Arhoolie.

“The Life and Times of Rose Maddox,” a television documentary produced by the (San Francisco) Bay Area Video Collective, was filmed last year and is now being offered to the Public Broadcast Service. Another film done in 1983, featured Rose singing Woody Guthrie’s “Philadelphia Lawyer.” The show aired nationwide in March of this year on PBS. It was Arlo Guthrie’s documentary tribute to his father, “Woody Guthrie: Hard Travelin’.” Rose tells Arlo in the show how she learned the song from Woody while they were both playing for tips in Northern California saloons. That song was one of her biggest hits, and probably Woody’s first.

Her version on the comic ballad is enshrined in the Smithsonian Institution’s folk music collection. She still treasures a letter of appreciation from Woody, penned in his bizarre calligraphic style, while laid-up in a hotel room.

This year also marked the appearance of a new audience for Rose —youthful members of the New Wave cult. It seems that some of the rowdier songs from Rose’s days performing with her brothers have been reissued on European labels (one disc was at the top of the European charts last year). The youngsters, hearing Rose Maddox for the first time, think she and her proto-rockabilly tunes are something new. Rose has had a couple of singing dates in the big Los Angeles clubs that cater to those pink-and purple-haired kids. She’s thrilled by their enthusiasm, but admits it’s a little hard to go back to that loud, raunchy music. Songs like “Those Wild Young Men” aren’t easy for a peaceful grandmother to attack, but she does, and the young people love it.

“There are notes in that tune that have to be brought up from the toes,” she says.

Rose is finding an appreciative audience on another cultural frontier these days-Alaska. She’s had four engagements there this year and the frozen North seems to have warmed up to her: the miners pay her with gold nuggets.

Wherever Rose goes and whoever is in the audience —the young Los Angeles blue-hairs, the older suburban blue-haired ladies who went to a Maddox Brothers and Rose dance on their first date, or the pickers at a bluegrass festival —it is the totally uninhibited, full-throated singing style that turns the crowd on. They are hearing the real thing, and they know it.

They are hearing a music that looks back to the rural Southern roots of families like the Maddoxes, but looks forward to Elvis Presley and the Nashville sound of today, with stops at all the stations in between. It’s no wonder that a bluegrass crowd loves Rose —there is a respect for the past without getting maudlin about it, an upbeat spirit of fun, and above all a tremendous regard for musicianship. If Rose should ever take time out from her singing schedule to coach girl singers, as she has sometimes thought of doing, the results should be remarkable.

Up to now, the only way anyone has ever been able to learn from Rose is by listening to her records or following her around, as Janis Joplin admitted she did. A 1960s folk music recording artist at one of Rose’s record-signing parties this year said, “I wanted to sing just like her and I don’t care who knows it!” Many a country star has gone through her Rose Maddox sound-alike phase.

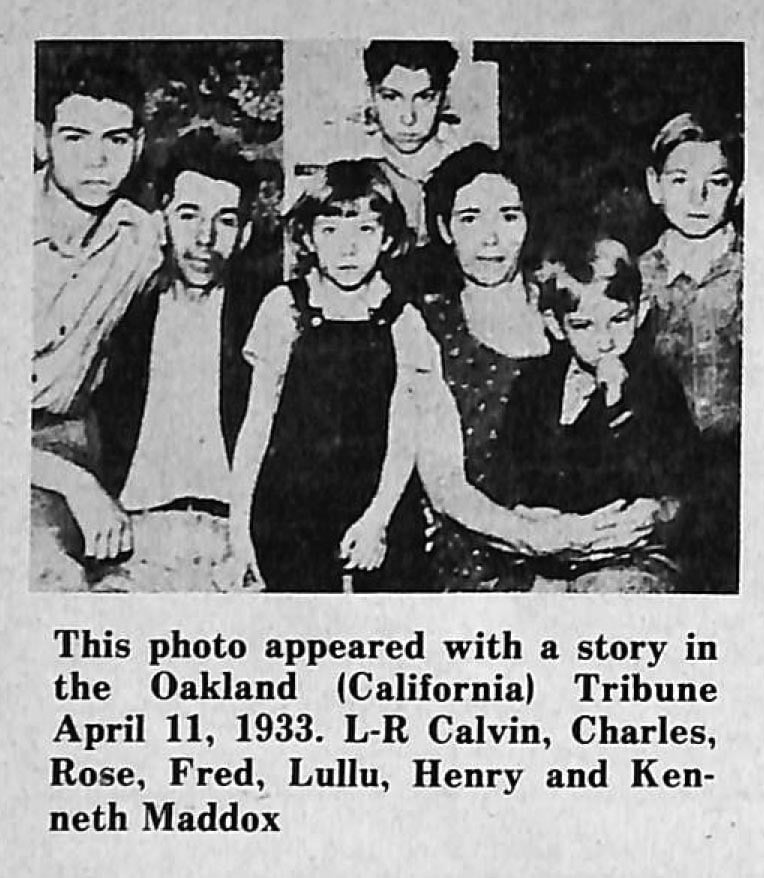

The story of how the Maddox revolution began, in the dark days of Depression and Dust Bowl, is a rich slice of Americana. When Rose was seven years old, drought and hard times forced the Maddoxes off their sharecropping farm near Boaz, Alabama.

“Mama decided we were going to California, ‘Where you could just pick the gold off the trees,’ ” Rose recalls. All their possessions were sold and with the $35 realized from the sale, Rose, her parents and four of her brothers started hitch-hiking west. During one of their frequent stops to earn money for food, the family met a young couple who taught them how to ride the freight trains.

There were thousands of homeless Americans on the road in 1933, but few families with children played the dangerous game of grabbing a seat on a moving boxcar. The railroad workers were touched by the sight of little Rose and conspired to get the family to California, hiding them from the railroad bulls. The cops were especially dangerous in Texas, Rose says, because “They just loved to shoot.”

But at every stopping place word would have gone ahead that the family was coming through and they were safely spirited from train to train. Often they would be met by the Salvation Army, who fed and encouraged them. When they got to the end of the line, in Oakland, California, they were met by the mayor of Pipe City, a community of wayfarers living in big sections of unused sewer pipe. The mayor gave the Maddoxes his own pipe.

The family didn’t linger in Oakland, but headed up into the foothills to try their hand at gold-panning. This was no way to feed a big family and things got so bad that her parents tried to give Rose away. But her new family found Rose’s high spirits too much to handle and Rose went back home. The family survived, Rose survived, and you can still hear plenty of that American determination in her music today.

The Maddoxes became fruit tramps, working the crops up and down the West Coast. Rose was growing up in a Steinbeck novel, in a Dorothea Lange photograph; learning songs from every reach of a country too poor to know it was poetic to be poor. Rose hates to look back, never gives in to self-pity and when she remembers how this desperate, hand-to-mouth existence gave birth to her life in music, she makes a joke out of it: “My brother Fred was tired of working and decided that music was an easier way to make a living.”

Everyone in the family played instruments and sang, and there was an uncle back home famed as a musician, composer and teacher. Fred talked his brothers into forming a band.

Then he talked a Modesto furniture store into sponsoring a daily radio show on KTRB. The store owners insisted that there had to be a girl singer, something Fred hadn’t counted on. But he quickly agreed, assuring his sponsors that the band had the “greatest girl singer in the world,” without mentioning that she was only 11 years old. That was the end of Rose’s childhood, the start of a career that now spans more than four decades.

The band received no pay from the radio deal, standard practice in those days, but they used the show to publicize their dance dates —dances, street corners and saloons along the rodeo circuit, playing for tips from cowboys out on a spree. They played, too, for their fellow fruitpickers, in the migrant farmworker camps.

Woody Guthrie might sing songs of social significance, but the Maddoxes, playing the opposite corner, were just hellbent on entertaining. They seemed to find the right formulas and more often than not people at the dances would crowd up around the bandstand, enthralled, not dancing at all.

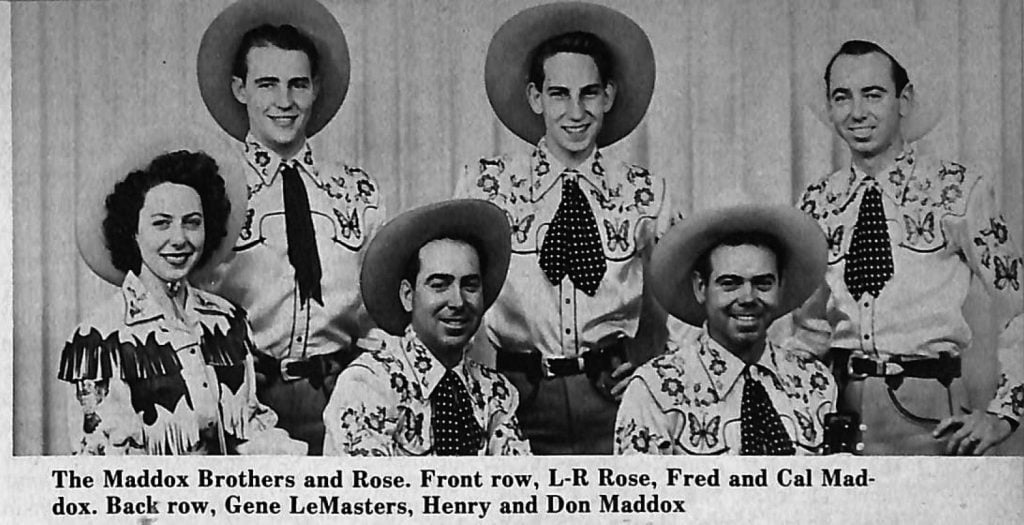

They may have lacked slick technique or sophisticated management, but the Maddoxes tried everything else: outrageous comedy routines, gaudy costumes to back up their brag “The most colorful hillbilly band in America,” and a vital new music, an amalgam of many sources. Rose still calls it hillbilly, but it came out of gospel, swing, bluegrass, and American folk music. It has been called California Country and Okie Boogie. The influences were as diverse as Jimmie Rodgers and The Sons of the Pioneers.

The Maddox Brothers and Rose were entertaining people like themselves, uprooted from a traditional life, looking backward with homesick feelings to the past, yet eager to adopt the ways of a new country. The Maddoxes listened to everything, tried anything that would work. But what held it all together was the unrestrained and increasingly rich and expressive voice of Rose Maddox.

An important turning point in the early fortunes of the group came in 1939 when they won a big competition at the California State Fair, defeating 15 other hillbilly bands. The top prize was $40 and a daily show originating on Sacramento’s KFBK and broadcast throughout the West on one of the early regional networks. A few years later a young mother in the Pacific Northwest became a Rose Maddox radio fan—Loretta Lynn.

The family moved to Sacramento and again using the radio show as a base, ranged widely for one-night stands on the weekends. They were making good money now, putting hundreds of thousands of miles on their Cadillacs each year.

World War II put a stop to all that. The boys all went into the service and Rose went out on her own. Not too far out, however; her mother, Lulla, kept a close eye on her and made sure that no agent, promoter or band leader took advantage of her. It wasn’t easy for a woman to work as a solo performer in country music in those days. Bob Wills refused to take her on and an exasperated Rose threatened “When my brothers get back from the war we’re going to put you out of business!” Telling the story years later, the king of Western swing conceded “And they darned near did.” The Rose Maddox-Bob Wills combination never came about, and it is left to fans of both to dream about what it might have been like.

After the war, the band re-grouped and came back stronger and flashier than ever. By the later ’40s they were probably the hottest act of their kind on the West Coast and at the height of their fame and influence. Merle Haggard was one of a thousand young musicians who heard them on the radio and at dances. It was out of respect for the Maddox achievement and his own musical roots, that Haggard offered himself and his band to back Rose on her most recent recording, the aptly titled “Queen of the West.” A still younger artist, Emmylou Harris, said she felt “honored” to be in the album, singing sweet harmony with Rose on two of the tunes.

As the band’s showmanship reached a higher pitch, fine musicians were brought from outside the family and jazz, swing and rock elements were added to the mix. Yet they retained close ties to traditional country music and Rose made her Grand Ole Opry debut in 1949 singing “Gathering Flowers For the Master’s Bouquet.” It was a song that was to prove a popular favorite over all the ensuing years, and a song Rose was to sing at her son’s funeral.

Some old 16-inch transcriptions of the Maddoxes early radio shows survived and have been reissued, but their commercial recording history began after the war. Their first contract was with Four Star and some of those cuts, too, have been reissued by Arhoolie. Later the band joined Columbia and stayed with that label through the early 1950s. Columbia, unaccountably, tried to tone down the band’s antics.

The Maddoxes often played in the huge dance halls that dotted the California landscape in those days. Many budding young performers stood at the foot of the stage in wide-eyed admiration of the rambunctious Maddoxes, and sometimes were invited up on the bandstand to join in. George Jones was one of them and Rose still thinks he’s the greatest male singer around.

Whole families would attend those big dances, but with the advent of television and the kind of affluence that made babysitters possible, family entertainment shifted indoors and adult entertainment was focused on the nightclubs where liquor was served and children excluded. The economics changed radically and, as Rose sees it, traveling bands like the Maddoxes were supplanted by the house bands, who worked more cheaply. In fact, as more young people entered the business, it became harder for the professionals to make a living, a situation even more common today than it was in the ’50s. Most of the old dance halls are closed now, boarded up, replaced by shopping centers, turned into flea markets.

The Maddox band broke up in 1956. Rose stayed on the road as a solo performer, or with her brother Cal. After Cal’s death she was on her own again. Henry and Cliff Maddox have also passed away; Fred is living in retirement in Delano, California, and Don Maddox has a 600-acre cattle ranch on the edge of Ashland, Oregon, the small college town where Rose also lives.

The first years as a single were hard for Rose. She had to overcome the notion that, as she recalls it, “She can’t do anything without her brothers.” It had been worse before the war, when Rose was one of a handful of women professionals in a male-dominated business. “Back then,” Rose says, “women were supposed to stay home and keep in the background.”

Never one to stay in the background, Rose brought herself to the attention of two TV broadcasters, Black Jack Wayne in San Francisco and Cliff Stone in Los Angeles. They featured her on live country music shows, and Rose was on her way again. She did some recording for smaller labels and then got a contract with Capitol in 1959.

Some of her big successes in the early ’60s were tunes like “Gambler’s Love,” “Kissing My Pillow,” “Sing a Little Song of Heartache,” “Lonely Teardrops,” “Somebody Told Somebody,” and “Bluebird, Let Me Tag Along.” “Heartache” stayed in the top ten of country charts for four months.

In 1961 Rose and Buck Owens had an unusual double sided hit with their duets “Loose Talk” and “Mental Cruelty.” The following year, at Bill Monroe’s suggestion, Rose made her “Bluegrass” album, backed by Monroe, Don Reno and Red Smiley. Later there were albums on the Uni and Takoma labels. And she was traveling widely, touring Japan and Europe, criss-crossing the states with Johnny Cash, and playing the Opry regularly.

The eclectic repertoire of someone who has been raising the roof for more than forty years is reflected in Rose’s newest disc, “Queen of the West,” on the new Varrick label brought out by Rounder. With Haggard and The Strangers, she is backed by some of the greatest musicians in the business today: Guitarist Roy Nichols got his first job, at the age of 17, with the Maddox Brothers and Rose; fiddlers Tiny Moore and Gordon Terry; guitarist Eldon Shamblin; steel guitarist Norman Hamlet; Don Markham on trumpet and sax; Biff Adams, drums; Mark Yeary, piano; and Dennis Hromek, bass. Merle pays glowing tribute to Rose in introducing her on the soulful Freddy Powers song, “Cold in California.” Haggard is heard throughout the record on lead and rhythm guitar and on fiddle; his acoustic guitar playing is amazingly eloquent. Merle’s wife Leona Williams plays guitar on the rousing opening number of the album, Tommy Collins’ “Down, Down, Down.”

Other songs on the album are Merle’s comic “Downtown Modesto” and his mysterious “Shelley’s Winter Love;” “Oklahoma Sweetheart,” a long-time favorite of Rose’s audiences; a real twangy love-song called “Alone With You;” Fred Rose’s wistful “Foggy River;” a complex, story-telling ballad “Mr. Jackson;” Don Reich’s folksy miner’s tune, “Somebody’s Looking For Gold;” and the raunchy “My Love is Just Too Hot For You!” Emmylou Harris sings harmony on “Down, Down, Down” and “Foggy River.”

With a hectic year of singing and recording behind her, Rose may take off a few days to “rest” with her grandchildren, but she rarely takes a real vacation.

Rose hopes to hit more of the Eastern and Midwestern festivals next year. If so, thousands of bluegrass fans are going to find themselves loyal subjects of the Queen of the West.