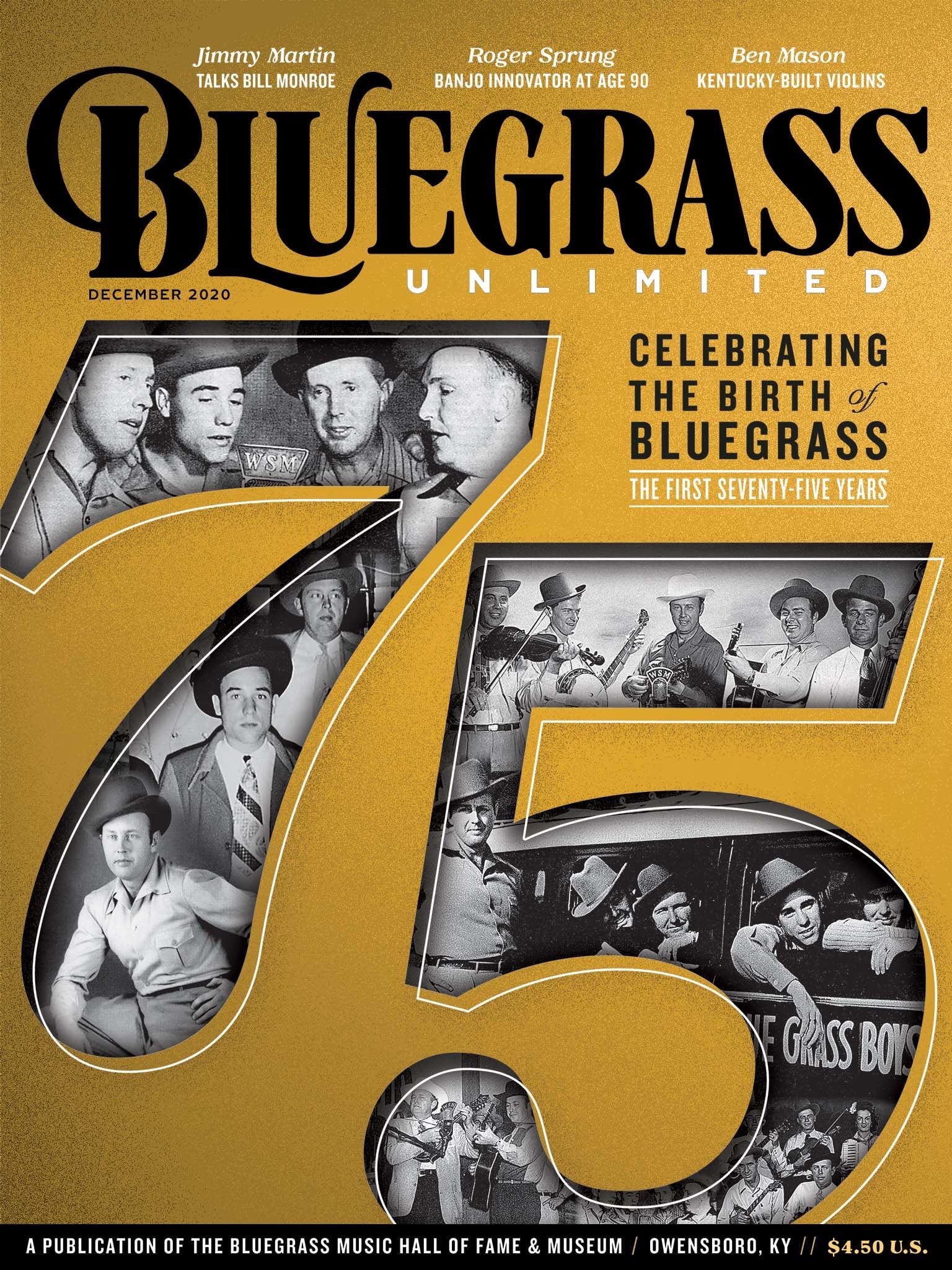

Home > Articles > The Artists > Roger Sprung: The “Godfather of Progressive Bluegrass” at Age 90

Roger Sprung: The “Godfather of Progressive Bluegrass” at Age 90

Who is the big man in the white shirt, black slacks and two-tone shoes, crowned with a homburg hat? And is he really a pioneer and living legend of the bluegrass banjo?

The answers are: Roger Sprung, and yes, yes indeed.

Roger was a central figure in the Folk Music Revival of the 1950s and ‘60s. His virtuosity at playing an almost boundless variety of music on the 5-string has made him to many fans the godfather of newgrass – or what Roger terms “Progressive Bluegrass” (from which he named his band, the Progressive Bluegrassers).

“One of my biggest, early influences was Roger Sprung.,” says Tony Trischka, himself a banjo master heralded for boundary-removing musical explorations. “I was captured by Roger’s wide-ranging repertoire – Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever”, “Mack the Knife”, “Malaguena”, “Greensleeves”, to name a few items that fell outside the standard Bluegrass repertoire.”

But as Tony also points out: “Bill Monroe thought enough of him to invite him onstage whenever they were at a festival together.”

Now, along with the acclaim that Sprung has won over his long career – for his entertaining festival and club performances, now-classic albums and for winning the title of World Champion Banjo Player at the 1971 Union Grove Fiddlers Convention – have come additional celebrations, including an enthusiastic September 14, 2019, tribute concert in his home state of Connecticut and his induction this past August 30th into the American Banjo Museum’s Hall of Fame.

Plus, Roger turned 90 this year, his path to banjo fame having started when he was born on August 29, 1930, the son of attorney Sam Sprung and wife Peggy, in New York City. That place of birth was far from the Southern heartlands. But as things turned out, little Roger was perfectly positioned for what he would one day contribute to folk music and bluegrass.

At about age 5, Roger was started in music by a nanny who taught him to play piano by sounding the black keys with his knuckles. Roger soon expanded to the white keys on his own, then put together rudimentary but complete tunes to perform. He eventually took piano lessons and found joy in boogie woogie.

Then, in his late teens, elder brother George took him downtown to Washington Square Park, where a nascent Sunday afternoon folk music scene had blossomed among the surrounding marble, concrete and asphalt.

As Roger recently recalled: “I saw people of all ages playing all kinds of stringed instruments and things. And I thought, That’s for me!” He soon acquired a guitar (thanks to a grandfather who owned a pawnshop) — and then a 5-string banjo.

In those days, the banjo learning process, especially for non-Southerners, was catch-as-catch can. The young Sprung started catching all he could.

Professional and accomplished amateur musicians were moving into the Greenwich Village neighborhood adjacent to Washington Square, drawn by its history as an arts district and its now-vibrant folk music scene. Some of Roger’s earliest banjo lessons were from Tom Paley, a founding member of the New Lost City Ramblers old-timey revival band.

Later, Roger became a prominent banjo teacher himself with innumerable students over the decades. His initial learners came from some of the folk revival’s most successful ensembles: Erik Darling of the Rooftop Singers (who performed with Roger in the early 1950s group The Folksay Trio), Chad Mitchell of the Chad Mitchell Trio and John Stewart of the Kingston Trio. (Indeed, although Roger performed at major bluegrass festivals during the 1970s, ‘80s and beyond, he never concentrated on touring the Southern circuit, preferring to stay based in New York and later Connecticut, rounding out his music business with teaching and instrument sales.)

As the now-legendary Washington Square jams ramped up New York’s role in the revival, George Sprung became responsible for obtaining the weekly event permits from the city parks department. And his brother Roger, grown into a stalwart young man of 6 feet-plus with confidence and authority on the banjo, became the epicenter of many a bluegrass jam session.

The cover photo selected for Ronald D. Cohen’s landmark book Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940 — 1970 shows Roger, thronged by listeners in the park and jamming with then-teenagers Mike Seeger and John Cohen (who, along with Paley, were New Lost City Ramblers co-founders).

Later, Sprung’s jaunty stage attire of black slacks, white shirt, vest, and black & white brogue shoes, all topped by a homburg hat, became his visual calling card, serving him especially well during tours with cabaret singer Kay Starr, appearances on the shows of early television icons Garry Moore and Dean Martin, and appearances at Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall.

His first bands – the Folksay Trio and the Shanty Boys – had folk-focused repertoires. And Roger never abandoned a folk-flavored sound during his long career. One of his most beloved albums was Roger & Joan with his first wife, folk singer/guitarist/songwriter Joan (Sachs) Sprung. And his longest musical collaboration, spanning more than three decades, was with Hal Wylie, a singer/guitarist with a specialty in British Isles ballads who proved a loyal friend and resonant performing match. But after developing a formidable bluegrass technique, Roger applied it to a surprising spectrum of material.

As a lad, Roger had quickly rolled into the piano’s possibilities. Entering his twenties, he began exploring the 5-string’s potential for a variety of music. The process began easily (one might even say, innocently) enough. Roger had made serious forays down to the Carolinas and Virginia to learn traditional music at its source. The experience surely aided his later wins in contests for banjo (both bluegrass- and clawhammer styles) and autoharp at Southern fiddlers conventions. But now he began creating banjo arrangements of songs that he simply enjoyed –classical music compositions, Broadway musical numbers, selections from European folkways.

Certainly, Roger Sprung was not the only picker pushing the possibilities of the instrument. Pete Seeger’s 1955 album Goofing Off Suite included the pop music standard “Blue Skies” by Irving Berlin, plus compositions by classical music titans Bach and Beethoven. Earl Scruggs was jazz-influenced (“Farewell Blues” and “Bugle Call Rag” started as 1920s jazz orchestra compositions that Earl reinvented as bluegrass standards). Also, Don Reno was perfecting his jazz guitar-flavored banjo technique, just as Reno admirer Eddie Adcock later developed his own adventurously virtuosic style.

But as banjo picker and Nitty Gritty Dirt Band co-founded John McEuen noted in a tribute, Roger revealed “playing directions I had not thought to explore. His border-crossing explorations – like those of Reno and Adcock – brought me and many others to a new path to head down.”

An early co-traveler on Roger’s path was none other than Doc Watson. In 1963, Roger was about to cut his first album for Folkways Records. Doc was appearing in New York, and Roger asked if he’d like to play on the sessions. Doc readily agreed: His own deep repertoire reached from traditional Southern music into rockabilly and pop, making him a perfect choice as the album’s lead guitarist.

The exciting result, Progressive Bluegrass Volume 1, represents Doc’s first studio recordings (although earlier at-home sessions featuring Watson had been recorded by folklorist/musician Ralph Rinzler in 1961). And progressive it was, including “Stars and Stripes Forever,” “Mack The Knife” and “Greensleeves.” (Hardcore banjoists who teased Sprung about his straight-fingered picking hand technique would do well to absorb the final cut, a show-stopper version of “Bye Bye Blues” in which Doc is clearly working diligently to keep up with Roger.)

Tony Trischka agrees that Progressive Bluegrass Volume 1 is a classic. “There was something about Roger’s tone and feel that resonated for me at that point in my life,” he says. “His style seemed fun and insouciant. And, of course, Doc’s guitar was a sterling attraction.

“Listening back to his first album, with my current ears and sensibilities, there’s so much to admire there,” says Tony.

Subsequent albums in the Progressive Bluegrass series — now available through Smithsonian-Folkways and featuring highly talented Sprung stalwarts Jon Sholle on lead guitar and Jody Stecher on mandolin — are also highly recommended.

Last year, Roger experienced a minor but limiting stroke. Sprung fans and friends James Weisser and Raye Hodgson presented a tribute concert with fundraiser on September 14, 2019, to a near-capacity crowd at the Grange Hall in Oxford, Connecticut. The event featured Trischka (who had changed his performance schedule to be there), Connecticut bands Shoregrass from Branford and Coda Blue of New Haven, this writer, and James, Raye and Erick Feucht as a trio. Sprung, slowed but still sharp and emotionally spry, enjoyed the show from front and center with his wife Nancy and their daughters Jenny and Emily.

Personal appreciations — insightful, occasionally humorous and totally heartfelt — were sent by John McEuen (who affectionately recalled how, along with Roger’s picking, his “cool look of somewhere between a riverboat music man and a card shark appealed to me”) and Pete “Dr. Banjo” Wernick (Hot Rize member and former International Bluegrass Music Association president). These were read to the audience from the stage.

Other accolades have followed — most notably Sprung’s induction this past August into the American Banjo Museum’s Hall of Fame.

Established in 1998, the American Banjo Museum is located in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Master players of all banjo varieties are now immortalized in its Hall of Fame.

In consideration of Roger’s venerable 90 years of age (especially during concerns about the coronavirus pandemic), the Hall of Fame came to him. Erick Feucht and Kim Cornell, neighbors of Roger and Nancy in Sandy Hook, Ct., graciously hosted a professionally-produced video session in the living room of their historic 18th century home.

Roger was introduced via video link by Banjo Museum board member Johnny Baier in Oklahoma, who then turned the proceedings over to colleague Paul J. Poirer on site in Connecticut. Next, an excellent museum-produced documentary on Roger’s life and career was shown. Then Paul presented a visibly-moved Roger his Hall of Fame statuette. A brief interview by Johnny of Roger for the American Banjo Museum website followed (youtube.com/watch?v=68HrGyGY3xs).

But that was only half the celebrations: The day before, August 29th, had been Roger’s landmark birthday. His nine decades were honored with gifts and reminiscences by attending friend. While a scrumptious buffet was enjoyed, Roger and company were entertained with an impromptu concert by co-host Erick on guitar, Richie Hawthorne on bass, and this writer (another former Progressive Bluegrasser who Roger also happily calls “Richie”) on mandolin.

Roger and Nancy have been married for 30 years. Their daughters Jenny and Emily were adopted. Nancy characterizes Roger’s unreservedly loving part in their adoptions, at his ages 65 and 69, as “remarkable and so generous.”

This kindness and nurturing, she adds, extends to his life as a music professional. Nancy recalls a conversation thread about Roger on banjohangout.org. “What struck me over and over again was how many people recalled him as a very good person, so generous and helpful,” she says. “It makes me so proud of him.”

When asked what advice he’d give aspiring banjo pickers, Roger says, “You’ve just got to love to play.” And when asked what he’s especially grateful for in his long career, he immediately replies, “To make a living playing the banjo.”

And we, in turn, can be grateful to Roger Sprung for playing the banjo, livelier and livelier.