Ringing in the Changes

Geoff Stelling Bids Farewell to Banjo Making After 48 Years

It may seem an odd thing to say in an age when the options for professional-quality banjos are plentiful, but there once was a time when they didn’t extend much beyond Gibsons. But by the mid-70s, when Geoff Stelling was thinking about starting his own business building banjos, the quality of the once-formidable Gibson brand had slipped. It turned out to be the ideal time to found an independent banjo company.

Stelling saw enough success with the basic banjo design he devised at Stelling Banjo Works in the 70s to continue making his instruments with relatively few modifications for nearly fifty years. It’s only with the arrival of his 79th birthday this month (June)—and with nearly 8,000 banjos, mandolins and guitars to his name (7712 banjos—which include 7431 Stellings and the rest Foggy Mountain models—101 guitars, and 150 mandolins)—that he has decided to draw things to a close.

Stelling’s official retirement from the instrument-building world came in March of 2022. As much as being motivated by his own desire to move on, he was also having a hard time finding replacements for long-time employees who themselves were stepping down. “It finally drove me out of business,” Stelling said. “I had no choice but to do the same thing myself.”

The last banjo to be made at the renovated schoolhouse containing Stelling’s shop in Afton, Virginia, was completed on March 28. Stelling is keeping the banjo—one of his flagship Staghorn models—for himself. With his decision to cease production, the banjo stamped Serial No. 7431 is now destined to be one of many collector’s items Stelling and his employees have put out in the world.

Rather than produce museum pieces, Stelling said his main ambition was always to build “players” capable of meeting the demands of the best professionals. Stelling got his own insights into these demands from his time playing banjo in a group called Pacific…ly Bluegrass. He was then in the Navy, stationed in San Diego. The Gibson-style banjo he was playing at the time wasn’t quite to his taste. So he did what any enterprising musician with a mechanical bent would do: He built his own.

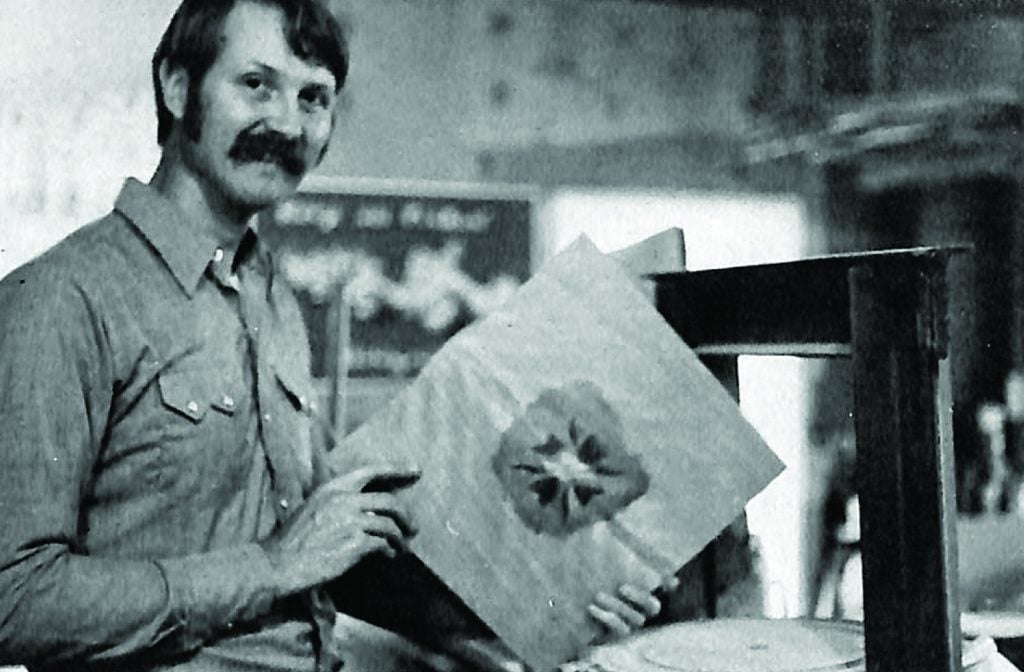

Encouraged by his early results, he started Stelling Banjo Works in 1974 nearby in La Mesa, California. His first innovation was to devise a new way of attaching tone rings to his banjos’ pots. One of the more dissatisfying aspects of the basic Gibson design to Stelling had always been the pot assembly. In Gibsons, and other similarly built banjos, the rims and tone rings are squared off and have to be cut perfectly to fit together tightly. Even when this is done just right, changes in humidity and temperature can cause the assembly to loosen.

Stelling’s time in the Navy had included time spent working on aircraft engines and propellers. Those experiences gave birth to a simple thought: Why not borrow from airplane design and make a tapered tone ring and rim that would fit together much like a propeller and propeller shaft? If the rim shrank over time, the tone ring would simply be pressed down further by the head, ensuring the fit remained tight. Stelling’s design was distinct enough to merit a patent—which he was able to secure only after traveling to Washington D.C. and demonstrating one of his instruments to a no-doubt bemused patent officer.

Stelling’s pot assembly was only one among many innovations he was to introduce over the years. By 1978 he had come out with his own designs for both tailpieces and nuts. His “pivot-pin” tailpieces can be easily adjusted up or down—to increase or relieve pressure on the strings—as well as to the left and right and in and out. His nuts are “compensated,” meaning they have notches of varying lengths to stop the strings in a way that mitigates some of the vagaries of stringed-instrument tuning. In another diversion from Gibson design, Stelling produced necks that were as thin as guitar necks. A standard banjo neck, he said, felt too much like “a baseball bat” in his hands. Once introduced, these features became standard on Stelling banjos. Combined, they gave rise to the distinct Stelling sound.

Whereas so many builders before and after Stelling have had their hearts set on chasing the pre-war Mastertone sound, Stelling had enough faith in his own ears and taste to pursue what rang true to him. “Once Little Roy Lewis started playing my first Masterpiece model in 1981, the Gibson crowd had been won over for the most part,” Stelling said.

Aside from ornamentation, the company in fact changed very little in the basic design of the various models it introduced over the years. The main components included fancy walnut and curly maple from Oregon and Washington state. With his company’s move to Virginia in 1984—he took it there to be nearer his then-wife’s family—he started securing wood for necks from a local manufacturer who had large pieces initially intended for rifle stocks. After many experiments with tone rings, he lit on a casting method that used centrifugal force to spin impurities to the outside of his bronze rings, where they could be machined away. By the early 2000s, he had ceased making his own rims and was instead obtaining them from Tony Pass, who was pulling “reclaimed” wood out of the Great Lakes.

With some of these design elements either in place or in the works, Stelling set about introducing the line of instruments that would make his name familiar to banjo players throughout the world. His first model was the Bellflower, followed shortly afterward by the Staghorn. Then came the minimally decorated Whitestar—which sold for less solely because of its lack of ornamentation—and the Golden Cross and Starflower. Throughout the years, he introduced various custom lines, such as the Scrimshaw series featuring engravings of whales, porpoises and other sea creatures. There were also models designed to the specifications of well-known players. The best-known of these—the Red Fox—was built for the recently deceased Bill Emerson of Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys, Country Gentleman and Country Current fame.

Of course, it wasn’t enough simply to build high-quality banjos. To succeed, Stelling had to get players to take notice. He did this first by bringing his banjos to every bluegrass festival he could possibly go to and setting up a booth to let passers-by give a Stelling a try. Also helpful were the many advertisements he placed in bluegrass publications such as Bluegrass Unlimited—where one of his ads occupied the back cover for many years. But, as is true for so many builders, the real advancement came when well-known players started using his instruments.

The musician perhaps most associated with Stelling is Alan Munde, who played a Staghorn on his early recordings with Country Gazette and solo albums. But there were plenty of others. Besides the aforementioned Emerson, the long list of illustrious Stelling players includes Ralph Stanley, Little Roy Lewis, Raymond Fairchild, Ben Eldridge, Terry Baucomb, Eddie Adcock, Bill Evans, Sonny Osborne, Ned Luberecki and Tony Trischka.

Alan Munde met Stelling when he moved to Nashville in 1969. The two quickly struck up a friendship. Munde said he remembers Stelling, then a student at Vanderbilt University, tinkering with an old open-back banjo he would play around town. His keen interest in instrument construction was already evident. Several years later, the two of them found themselves both in California. Learning that Stelling had started making banjos, Munde asked him to bring one up to Los Angeles. A life-long affiliation was born.

“I really liked the sound of it,” Munde said of his first Staghorn. “I’d say it was a much quicker sound. You didn’t have to play it quite as firmly as a Gibson to get a sound of it. And it had clarity all the way up and down the neck.” To this day, Munde almost exclusively plays Stellings. He still has his original Staghorn as well as a Crusader from the 2000s. Munde said, “I always say: You can make a banjo as good as Geoff Stelling, but you can’t make one better.”

Trischka, whose first banjo was a Staghorn and who later played Stelling Sunflowers on recordings in the 80s and 90s, said one of his clearest memories of Stelling came from a visit to the Stelling workshop in California. With Stelling on bass, they experimented with playing bluegrass with the standard rhythm turned around—having the mandolin chop on the downbeat and the bass hit on the upbeat. “It didn’t have legs,” Trischka said. “But it was fun.”

Trischka said Stelling not only deserves credit for reintroducing professional-level banjos to the market at a time when quality was sagging but also for being one of the most significant innovators of the latter half of the 20th Century. “He did a lot of rethinking of banjo construction,” Trischka said. “We all owe a lot to Geoff Stelling in the banjo world. He’s been really generous to me and supportive. So I’m sad to see he’s retiring.”

Luberecki, who plays banjo in The Becky Buller Band and has used Stellings on various recordings over the years, said that when he first set out to buy a banjo with his own money, there was no better builder than Stelling. His eventual purchase of a Staghorn in 1983 for $2,000 later led to a tour of Stelling’s shop in California. Stelling proved a gracious host, giving Luberecki a “Stelling doorstop,” a wedge-shape piece of wood from the same stock used to make the neck of Luberecki’s banjo. It remains one of Luberecki’s most-prized possessions.

Luberecki said Stelling perhaps deserves the greatest credit for not being afraid to be different. “In a world of Gibson Mastertone clones, Geoff was the first major banjo maker to radically redesign the way the tone ring and banjo rim come together,” Luberecki said. “We can always argue about which design sounds better (which is subjective, after all). But there is no question as to the quality of workmanship, premium materials, artistry and passion for innovation that Geoff Stelling brought to the banjo world.”

Bill Evans said, “Hearing the tone of Alan Munde’s banjo on his Banjo Sandwich album in 1975 was a life changer for me as an emerging professional player. It seemed like a different paradigm from what I had heard from any other player. I saved up every penny that I earned playing banjo at Busch Gardens in Williamsburg, Virginia in the summer of 1976 and was head over heels in love with serial no. 158, my own Stelling Staghorn, when it was delivered later that year.

“One aspect of the story of Stelling Banjos is that the instruments got dramatically better in this first decade, in my humble opinion. By 1981, I had purchased a Bellflower, like Tony Trischka’s Stelling, and this was the instrument that I played with Cloud Valley, my touring band, in the early 1980’s. Right before I left for California to start graduate work in Music at UC Berkeley, Geoff moved to Nelson County, Virginia, near where I lived in Charlottesville. I only got to visit the shop a few times before I headed west, but I cherish those moments and memories of time spent with Geoff. And to come full circle, Alan Munde was staying with me here in my New Mexico home and I got to spend some time playing his mahogany Crusader banjo. What a fine instrument! Congratulations Geoff on a job that’s more than well done and I hope you get to enjoy your retirement!”

Throughout it all, Stelling never felt a desire to put low-priced, starter models on the marketplace. That lack of interest in the beginner’s market was one of the reasons for his eventual split with Greg Deering, who had joined Stelling Banjo Works shortly after its founding in California and later went on to start Deering Banjo Company with its wide range of high-quality banjos at all price points.

Deering was only one of many future instrument builders to benefit from experience gained working in Stelling’s shop—Larry and Kim Breedlove were two others. Kim and his brother Larry worked for Stelling in California until Larry moved to Oregon to start Breedlove Guitars. Kim stayed with Stelling through the move to Virginia. After moving to Virginia, Kim worked for Stelling for two years before moving back west and buying into Breedlove Guitars after Larry left to move back to California and work for Bob Taylor at Taylor Guitars. Jeff Huss and Mark Dalton, the principals behind the Huss and Dalton guitar line also got their start at Stelling.

Huss said he came to Stelling after training to be a lawyer and with virtually no experience related to banjo-making save some time spent working with tools. As much as the craft of instrument building, Huss learned from Stelling about the great amounts of effort needed to keep production quality high. “When I started working in my garage on my own, I knew things had to be just right and had to be clean,” Huss said. “So I had that little start on a lot of people. I wasn’t going to stand for anything that looked a little sloppy, because that wasn’t the way we did it up there at Stelling.”

Even after discovering his winning formula early on, Stelling never stopped trying out new things. He released his first mahogany banjo since the 1970s in 2004: The Crusader, which featured a modified version of the classic Stelling peghead. In 2016 came the Afton Star, a relatively light banjo with no metal tone ring. He also, for shorter periods, experimented with making mandolins and guitars.

In the first article Bluegrass Unlimited published on Stelling (March 1976), the writer opined: “Geoff Stelling is that most fortunate of individuals, a man doing something he loves, being successful at it and enjoying it immensely.” Looking back on his career, Stelling can now say that being an independent instrument builder for nearly fifty years was by no means easy. “It is a tough industry to stay in business in,” he said. “A lot of people started out in business are no longer around.” But he also couldn’t have stuck with it for so long, and watched so many others come and go, if he wasn’t having at least a little fun.

With his retirement now official, Stelling is not only no longer making banjos but also is no longer accepting instruments for repair. He plans to soon compile and release a list of places where Stelling owners can bring their banjos to have them worked on. His online shop will meanwhile continue to sell hats, bridges, strings, truss-rod covers and other accessories, but only while the supplies last.

Stelling said any talk about finding someone else to run the business more or less petered out among the realization that skilled craftsmen and quality materials were getting only harder to come by. Banjo players, meanwhile, are now blessed with choices when it comes to professional-quality instruments. Even though new Stellings are no longer being produced, the thousands of quality instruments he produced in his career, and the use they’ve been put to by great players, will ensure that Stelling’s place in bluegrass history is a permanent one.