Home > Articles > The Archives > Riley Puckett—Country Music’s Pioneer Guitarist

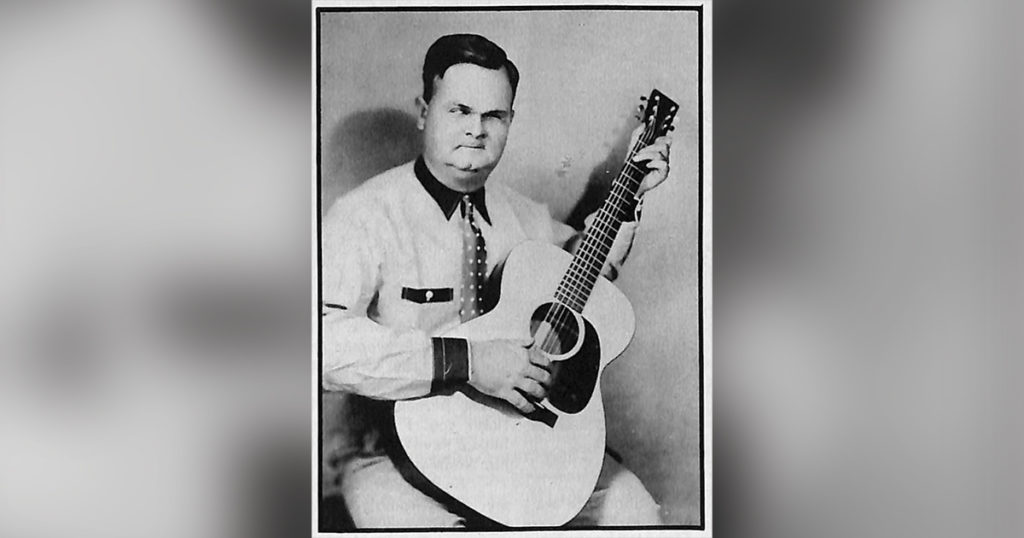

Riley Puckett—Country Music’s Pioneer Guitarist

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1984, Volume 19, Number 4

Enon Baptist Church is located just a few miles from the Atlanta suburb of College Park on a winding stretch of highway known as Stonewall Tell Road. Across the road from the church is a cemetery, full of sculptured granite and marble monuments. One of these monuments marks the grave of Riley Puckett.

There is nothing fancy about Riley’s monument. No musical notes or guitars are chiseled into its surface. There is not even an epitaph, only the name “George R. Puckett” and the dates of his birth and death.

If there were an epitaph, it might read something like this:

“George Riley Puckett. Early Hillbilly recording artist. Renowned as an innovative guitarist and vocalist, Mr. Puckett helped to pioneer country and bluegrass music through his recordings with the Skillet Lickers in the twenties and thirties. His admirers included such musical greats as Doc Watson, Bill Monroe and Jimmie Rodgers, and his career paved the way for countless other performers. Although blind, he was a visionary in the field of country music.”

Riley Puckett was born on May 7, 1894, in Alpharetta, Georgia, a small community just north of Atlanta. When he was three months old he developed a minor eye infection and through a misapplication of a solution of lead acetate (sugar of lead), a powerful astringent, Puckett was left sightless.

Shortly after his seventh birthday, Riley entered the Georgia Academy for the Blind in Macon. During the time he spent at the Academy, Riley learned ways to adjust to his handicap. He also learned to play the piano, a skill which developed a great deal of dexterity in his fingers. Around the age of twelve, he moved with his parents to Atlanta. There, sometime during his teen years, he taught himself to play the five-string banjo and later, the guitar.

Approaching adulthood with a severe handicap, Riley found most jobs closed to him. Like Blind Lemon Jefferson and others, he turned to music to earn his living. He began his career by playing at dances, parties, fairs and occasionally, on street corners.

By 1920, Atlanta had become a center for fiddling and hillbilly music, largely due to the nationally famous Georgia Old-Time Fiddlers’ Convention, held yearly in the Atlanta City Auditorium. In time, Riley’s proficiency on the guitar gained him admission to a clique of musicians which included Clayton McMichen, Gid Tanner and Fiddlin’ John Carson. Soon, Riley was appearing over radio station WSB as a member of McMichen’s Hometown Boys. His debut performance on Thursday, September 28,1922 brought enthusiastic reviews from the local press. “Already a favorite at WSB,” wrote the Atlanta Journal, “the Hometown outfit scored a knockout by introducing Mr. Puckett as one of their stars Thursday night.”

In 1923, the country music industry was born when Okeh Records recorded Fiddlin’ John Carson, one of Riley’s contemporaries. Columbia Records was now eager to get in on the game and soon A&R man Frank Walker (who later played a prominent role in the career of Hank Williams) had Puckett and Gid Tanner in the company’s New York studios. There, they cut what was to become that company’s first country records.

Puckett and Tanner’s first trip to the studio, in sessions held on two consecutive days, produced several breakneck fiddle tunes including “Buckin’ Mule” backed by Puckett’s guitar and Tanner’s whoops and hollers. In addition, Riley recorded “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane,” a cover version of John Carson’s first hit. On the flip side, Puckett sang his version of “Rock All Our Babies To Sleep,” complete with yodeling. Riley thus became, according to many, the first country performer to yodel on records, a distinction usually accorded to Jimmie Rodgers.

The recordings were an immediate success and the team of Puckett and Tanner quickly became Columbia’s star hillbilly attraction. A 1924 advertisement described the duo in these words:

“Not long ago, Gid Tanner with his violin and Riley Puckett with his guitar came, fresh from the mountains of North Georgia, to make records for Columbia.

“Gid has walked away with the first prize at some of the Old-Time Fiddler’s Conventions in Atlanta. Riley and his guitar are known to thousands in the south, who have heard him perform at county fairs. Hear these Tanner and Puckett records. No southerner can hear them and go away without them. And it will take a pretty hard-shelled Yankee to leave them.”

The success of the recordings brought Riley a new degree of affluence. Even though he was unable to drive, he soon used some of his royalty money to buy a new Model T Ford. One day in early 1925, Riley and a fellow musician named Ted Hawkins were driving back from Stone Mountain in the Model T when they were hit by a trolley car. The Model T was totaled and Riley was thrown from the vehicle and almost killed. He was taken to Grady Hospital with injuries to his head, legs and arms. Later, he was sent to his mother’s home to recuperate and Blanche Henley, an outpatient nurse, was assigned to care for him.

The future Mrs. Puckett had heard of Riley before while working as a nurse in Thomaston, Georgia. She was caring for a recuperating patient at the hotel at the same time that Riley was making an appearance in town. After she had gotten off from work one day, some friends invited her to go with them to see Puckett play. “As tired as I am tonight,” replied Blanche, “I wouldn’t go to see the Statue of Liberty waltz all over New York.”

Blanche remained at the Puckett home for about two months. Soon, just like in the old joke, Riley took a turn for the nurse. “One day I was there at the bed working with him and he just looked straight up and said, ‘Miss Blanche, you’ve got the sweetest personality of anybody I ever saw, and the sweetest disposition.’ Well, I didn’t think anything about it. I just went about my business.”

“A morning or two after that, he was getting better and I was fixing to leave. He said, ‘Miss Blanche, I’ve seen a lot of prettier woman than you are, but you have the sweetest disposition of anybody I’ve ever seen in my life, and the nicest personality. And I said. ‘Well, thank you.’ I was in love with him then, but I’d have died before I’d have ever let him know it.”

“So, a day or two after that he asked me, ‘What would you think about marrying a blind man?’ I said, ‘If I loved him, I’d marry a blind man quick as I would one with four eyes.’ And that’s the way it started.”

Riley and Blanche were married on May 18,1925. For a honeymoon trip, Columbia Records sent them to New York, where Riley made some more recordings.

Later that same year, Clayton McMichen signed with Columbia after an unsuccessful association with Okeh. Frank Walker quickly came up with the idea of forming a “super group” with Puckett on guitar, McMichen and Tanner on fiddle, and banjo player Fate Norris. The group, christened “The Skillet Lickers” soon became the leading hillbilly group of its time, a fact that McMichen attributed to Puckett’s guitar playing and singing.

It was Puckett’s guitar style that set the Skillet Lickers apart from other groups like Al Hopkins’ Buckle Busters and the Georgia Yellowhammers. Instead of merely providing a chordal rhythm to back the lead fiddles, Riley used the guitar to play intriguing bass runs and counter melodies.

Guitarists who listen to Puckett today on records consider him a first-rate flatpicker. In actuality, Riley was a fingerpicker. Both of Puckett’s hands, in fact, were capable of lightning speed. “When he was playing, every one of his fingers were moving,” recalls Blanche. His piano lessons at Macon undoubtedly gave him the necessary right-hand dexterity to accomplish this.

Puckett’s unorthodox but highly effective technique is doubtlessly due to his blindness and the fact that he was self-taught. His widow calls it “God’s gift. The first guitar he ever tried to play, he played it,” she explains. “He could play any kind of instrument in the world, any kind of instrument you’d hand him.”

Many guitarists have tried to duplicate Riley’s unusual finger style with little success. In addition, many flatpickers also have been influenced by his music. Among these are Doc Watson, who names Puckett as one of his major musical heroes. As a child in North Carolina, Watson listened to Puckett’s recordings and drew inspiration from the fact that, like himself, Puckett was blind. Riley’s style has also filtered down in the playing of Dan Crary, Norman Blake and the late Clarence White.

In fact, it may be said that Puckett’s playing provided the framework for bluegrass guitar style. Riley, for instance, was among the first performers to use the “G Run” prominently in his music and one of the first to employ heavy bass runs as back-up. It is no surprise that many early bluegrass guitarists emulated Puckett: At the time, Puckett was one of the few hillbilly guitarists worth emulating.

Another big plus for the Skillet Lickers was Riley’s singing. Unlike early hillbilly artists like Henry Whitter and John Carson (whose voice was once described as “plu-perfect awful”), Riley had a rich, mellow, baritone voice, free of any trace of nasal twang. Admirers of Riley’s singing included many of his comtempories, among them Jimmie Rodgers, who even did cover versions of some of Riley’s songs.

As the Skillet Lickers, Puckett, McMichen and Tanner made over 80 records between 1925 and 1931. “We got to playing, making big hit records, and then we got on the road and made some money,” recalled Gid Tanner years later. The Skillet Lickers could rightly be termed hillbilly music’s equivalent of the Beatles. They were creative, fiercely independent, and, at times, a bit crazy. While other groups aped the backwoods image by wearing overalls, the Skillet Lickers performed in three-piece suits and tuxedoes. Their recording sessions on Pryor and Peachtree streets in Atlanta had party atmosphere. (There is a story, which may or may not be true, that at one session in an Atlanta hotel the bathtub was filled with white whiskey and a gourd dipper was hung on the faucet.)

This outrageous sense of humor is reflected in the “Corn Licker Still” series, fourteen recordings which combined music and comic dialogue about a group of Georgia moonshiners. The records served as “samplers” of other Skillet Licker recordings like “Pass Around the Bottle,” and “Devilish Mary.”

The Skillet Lickers, however, like the Beatles, began to drift apart. Clayton McMichen began to break away from the old-time format and formed a second band, the Georgia Wildcats. Tanner, clinging to the old-time sound, dropped out of the picture for a while, as did Fate Norris. According to Blanche, the breakup came while the group was playing over radio station WCKY in Covington, Kentucky. “There was some kind of controversy between the musicians and we left,” she remembers. “As to why, I don’t know.”

Riley apparently remained on good terms with everybody in the group. Later they re-grouped as “Clayton McMichen and the Skillet Lickers” and played again over station WCKY.

In 1934, Gid Tanner arranged a recording session which took place on March 29 & 30 in San Antonio, Texas with the Victor Company. Puckett, along with his friend Ted Hawkins and Tanner’s 17 year old son, recorded 24 sides as “Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers.” From these sessions came the famous recording of “Down Yonder,” one of the biggest fiddle tunes of all time—a recording which remained in print decades after its original release.

With Blanche and their baby daughter traveling with him, Riley continued to work at various radio stations east of the Mississippi. He performed on stations in Huntington, West Virginia, Cincinnati, Ohio, Gary, Indiana, Harvey, Illinois, Chicago and Knoxville. Throughout the week, Riley played concerts in the station’s listening area. “The station booked big auditoriums where they’d be 5000 people sometime,” recalls Blanche. Sometimes Riley worked as a solo act, using the new all-metal guitar he had purchased in 1937. At other times, he had his own band. “Smoky Jenks was his comedian,” remembers Blanche. “If he was coming home at night. Smoky would say, ‘Riley, are we going to get any ol those good hot biscuits and fried chicken tonight?’ Riley would say, ‘Well, I guess we will.’ That’s the way I knowed he was coming home. The station wouldn’t let him come right out and tell me he was coming home.”

Riley continued to record up until 1941 for Victor’s Bluebird label with one session for Decca in 1937. His songs included traditional hillbilly tunes like “Curley-Headed Baby;” blues tunes like “Waiting for the Evening Mail;” novelty songs like “I Wish I Was Single Again;” western ballads like “Boots and Saddle;” and pop tunes like “How Come You Do Me Like You Do?;” and Sigmund Romberg and Oscar Hammerstein’s “When I Grow To Old Too Dream.” By the time of his last session on October 2, 1941, he had recorded over 80 sides as a solo artist after leaving the Skillet Licker.

The wide range of Riley’s repertoire testifies to his eclectic nature. Riley listened to “anything and everything” and was constantly attuned to the radio. “The radio was the first thing that went on in the morning,” says his widow. “He could sit and listen to a song on the radio one time and just pick it up and sing it all the way through and not miss a note.”

Riley had built his first radio, a crystal set, from a kit. He possessed a phenomenal memory and a surprising degree of mechanical aptitude. On the personal side, he was an extremely gentle man. He did, however, have an Irish temper. “He was one of the sweetest people that you could ever imagine…until you made him mad,” says Blanche. “When he got mad, he had the awfulest temper that I have ever seen in my life. But when it was over, he was back to his old sweet self.” Despite the Skillet Lickers’ wild image (or maybe because of it), Riley was apparently a deeply religious man who often sang at revival meetings.

Sometime after 1941, Riley, McMichen and Bert Layne reputedly played the Grand Ole Opry. Riley also appeared over Knoxville radio in addition to his performances over Atlanta stations. The last Atlanta station he played over was WAG A, along with a group called the Stone Mountain Boys.

In 1946, Riley was playing throughout the week over station WGAA in Cedartown, Georgia, and staying with friends in nearby Rockmart, when tragedy came unexpectedly. “He had a little pimple on the back of his neck,” recalls Blanche. “On Sunday afternoon he said, ‘Honey, come here and mash this thing. It’s kind of hurting me.’ I looked at it and said ‘Uh-uh, I’m not going to do it because it’s got to come to a head.’ And so he went back over to Rockmart.

“So he was gone during the week and the next Wednesday afternoon a man pulled up in front of my driveway and said ‘Miss Puckett, Riley’s sick and we want you to come and see about him.”

The pimple had turned into a boil and, the next morning, Blanche and a local doctor lanced it. Blanche took Riley home and tried to persuade him to go to the hospital. “He was stubborn as an ox,” she recalls. “He said, ‘I’m not gonna live and I’m gonna stay right here with you and the baby.’ After he got so far along I just called the ambulance and they took him anyway.”

Riley died on July 13,1946 at Grady Hospital from blood poisoning caused by the boil. His funeral was held at Enon Baptist Church with Gid and Gordan Tanner among other Atlanta musicians as pallbears. For the next four weeks, Atlanta’s WAGA played his records as a tribute to him.

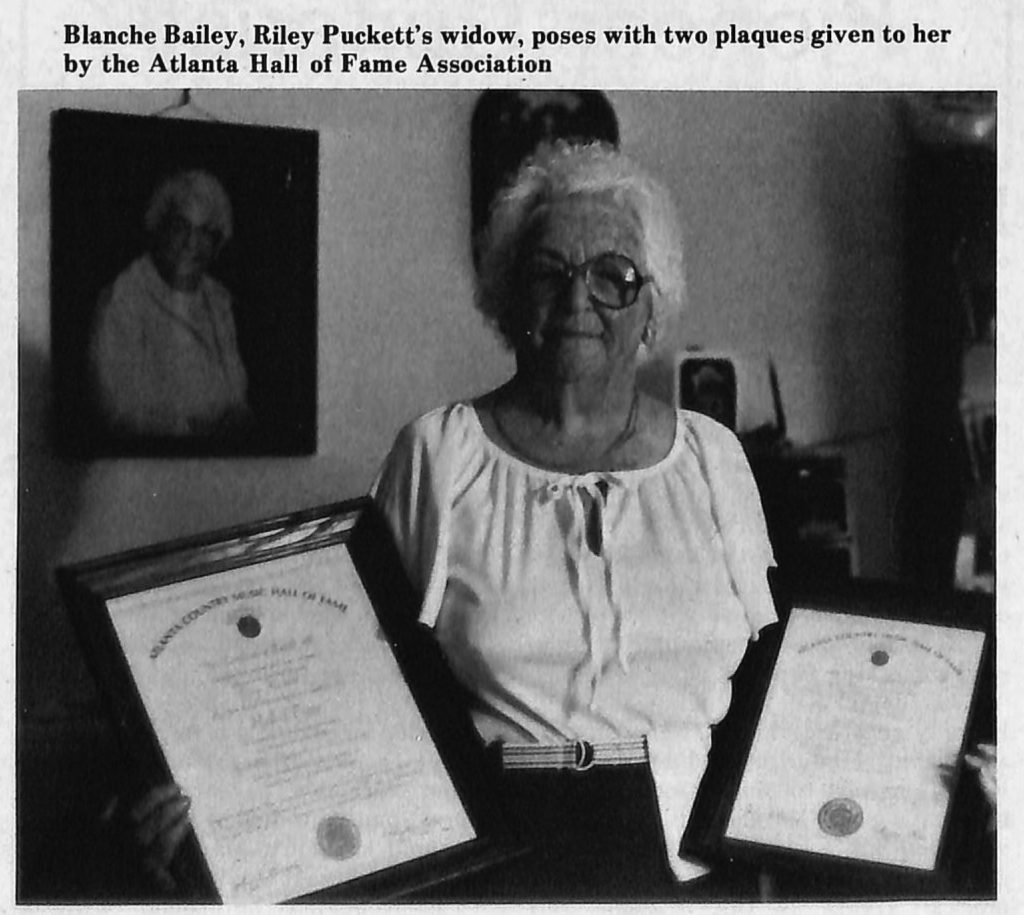

Some time after Riley’s death, Blanche married Clyde L. Bailey. She now lives in Riverdale, Georgia with her daughter from that marriage and her son-in-law. Her other daughter, from her marriage to Riley, lives in Winter Haven, Florida.

In recent years, Blanche has worked to keep Riley’s memory alive. She was present at the opening of the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, where she donated Riley’s pipe to the museum. She recently accepted a Hall of Fame certificate on behalf of her late husband from an Atlanta organization which intends to set up a Hall of Fame for Georgians who had been instrumental in the growth of country music. (See BU, March 1983) She keeps her awards in her bedroom, along with the two framed photographs of Riley, several tapes of his music, and a complete discography of all his recordings.

Had Riley not been blind, Blanche believes that his impact on music would have been even greater. “He was an artist unto himself.” she says. “He would have outdistanced most or all singers of that time. She is especially proud of Riley’s guitar playing. “Maybe I’m prejudiced,” she admits, “But when he wanted to, Riley could run rings around Chet Atkins.”

Blanche would like to see Riley elected to the Hall of Fame in Nashville but is not overly optimistic about his chances. “There’s so many big Ts’ and little ‘yous’ in the music business nowadays,” she explains. “Every hog wants to get to the trough first.”

To those who have heard him on record and marveled at his voice and lightning-fast licks, however, it has been evident for a long time that Riley was one of the head hogs at the trough to begin with.