Home > Articles > The Tradition > Richard Hefner of the Black Mountain Bluegrass Boys

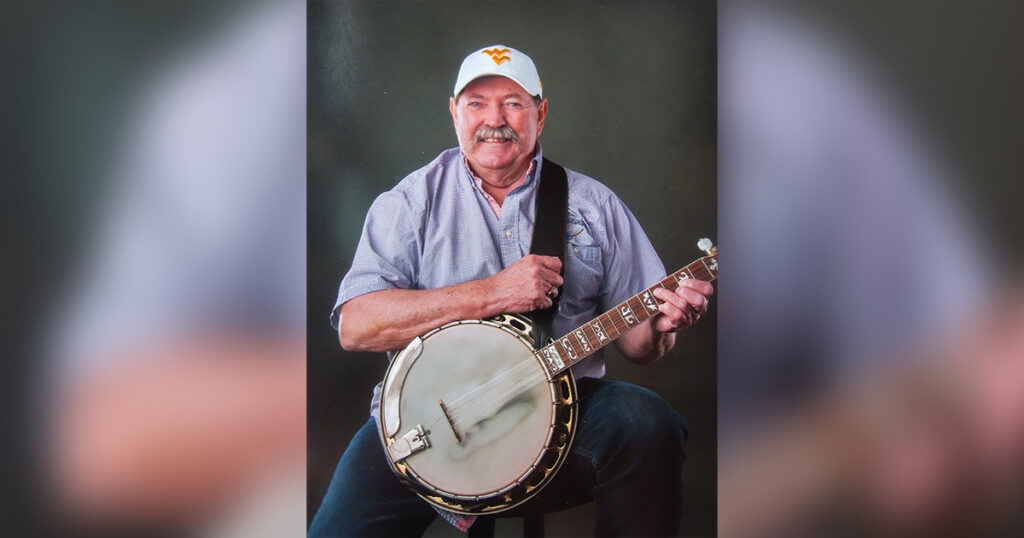

Richard Hefner of the Black Mountain Bluegrass Boys

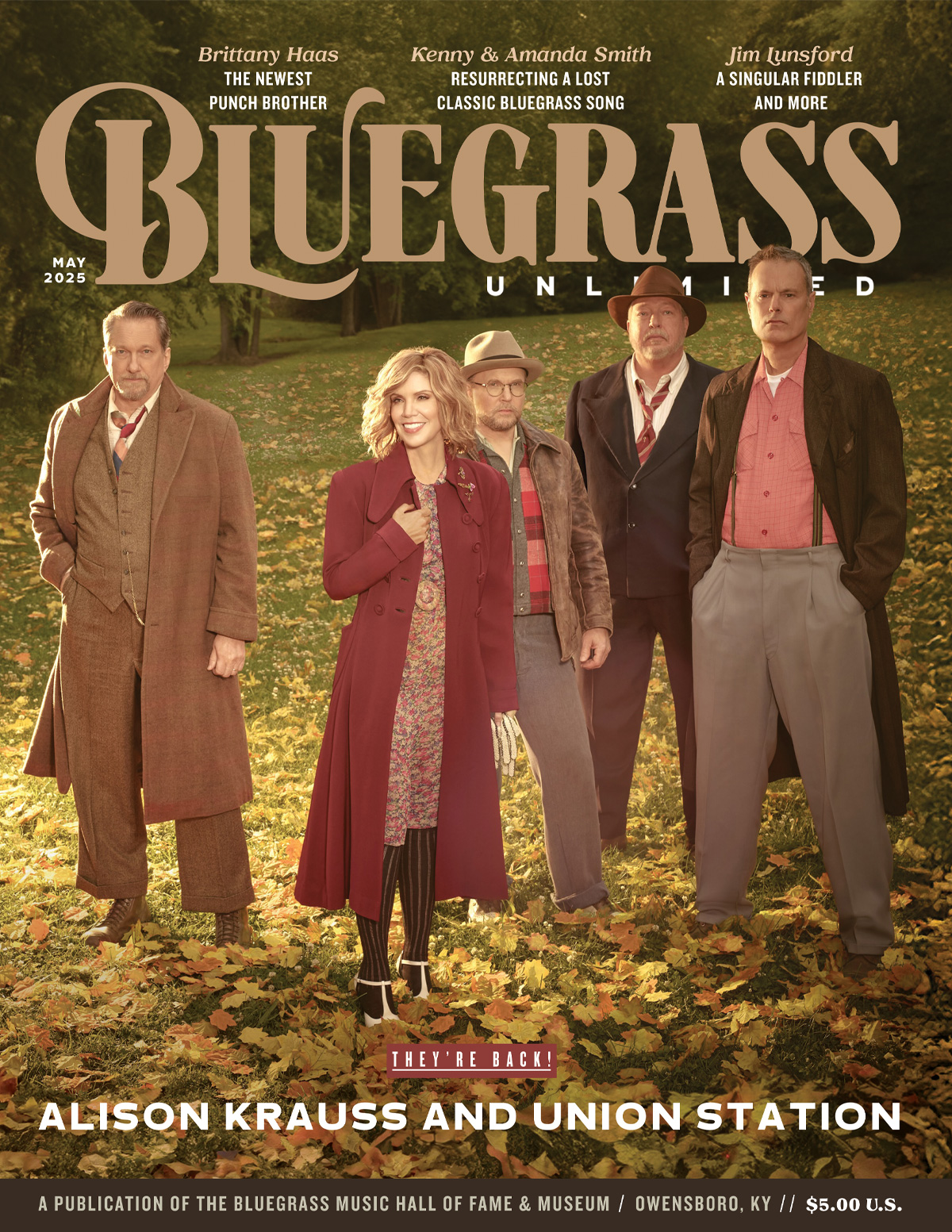

A West Virginia Bluegrass Legend’s Signature Song Revived for Modern Times by Kenny and Amanda Smith

Pocahontas County is not only one of the most beautiful counties in West Virginia, it is one of the most nature-filled regions in all of the 400-year-old Appalachian Mountain chain.

The county, which contains the headwaters of eight rivers, also features the small town of Marlinton, West Virginia. What separates Marlinton from other mountain towns like Boone, North Carolina, Huntington, West Virginia, or Johnson City, Tennessee, is that the latter places contain a university while Marlinton does not, leaving Pocahontas County mellow and quiet.

Bluegrass legend Richard Hefner was born and raised in Pocahontas County in a place called Mill Point, which exists on RT 219 in-between Marlinton and Lewisburg, West Virginia. When you travel through that turn in the road while on the way to the Cass Scenic Railroad, the arctic fauna of the Cranberry Glades, or the ski slopes at