Home > Articles > The Archives > Remembering The Kentucky Colonels—The Bluegrass Life Of Roland White

Remembering The Kentucky Colonels—The Bluegrass Life Of Roland White

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1987, Volume 21, Number 8

It was some band. I can still remember my amazement hearing the Kentucky Colonels for the first time, wondering how any five individuals could play music with such speed, drive, and excitement, song after song. There was an unbridled — almost wild-eyed — enthusiasm to the Colonels’ playing that few bluegrass groups could match in the 1960s —and still can’t. But intensity wasn’t the whole of it—these guys played bluegrass (“You is either playin’ it, or you isn’t” someone once said) and, what’s more, they weren’t even from the so-called “Bluegrass Belt” of the southeastern states—where all “good” bands were thought to originate.

It was indeed a band with musical flair, both individually and collectively, but it is only now, nearly twenty years after the demise of the Los Angeles-based Colonels, that many people are beginning to realize this. Though much attention has been payed to the astonishing abilities of guitarist Clarence White, and to a lesser extent, fiddler Scott Stoneman, who played with the band for about six months, there has been relatively little focus on the group as a whole. The neglect of the Kentucky Colonels is in some ways understandable for they were not in the geographical bluegrass mainstream of the time, and it is only recently that many of their live-show performances have been made available on record, while studio recordings of the group were out of print for years. The effect of these recordings is to confirm what devotees of the band have known all along: This was a major bluegrass group of its era, capturing the soulful essence of the music in an expressively spirited manner.

It is music that bears repeated listenings, not just for Clarence White’s thrilling, head-first explorations on lead guitar, or Scott Stoneman’s hair-raising technical accomplishments on the fiddle, but for the more subtle aspects of the group’s offerings: Clarence and brother Roland’s distinctive vocal blend: Roland’s adroit, fluid mandolin leads; the behind-the-scenes drive of Clarence’s impeccable rhythm guitar, Billy Ray’s spirited banjo, and the forceful but economical playing of bass players Eric White and Roger Bush. Given the Colonels extraordinary individual talents and their collective musical horsepower, it is a wonder they were somehow able to blend all of it into a controlled, dynamic, band sound.

The story of the Kentucky Colonels begins, oddly enough, in the state of Maine, where Roland, Eric, and Clarence White were born in chronological order (Roland was about six years older than Clarence) to French Canadian parents. In spite of the somewhat unusual (for bluegrass) circumstances, the youthful White children benefited from a father who was a fiddler and collector of country music records. Thus it can be said that at an early age Roland was presented with a “tater bug” mandolin, Eric a tenor banjo, and Clarence a guitar. Clarence was so small that, initially, Roland had to alternate strumming the instrument while Clarence chorded, or chord the instrument while Clarence strummed. History will record that Clarence ultimately put it all together.

In the early 1950s the White children (there being a total of 17) were uprooted from their northeasterly domain and moved diagonally across the country to Southern California where the elder White had accepted a job working on hydro-electric projects. By this time Roland, Eric, Clarence, and a sister had developed sufficient skills on their instruments to enter a talent contest on a local radio station which, to their surprise, they won. This led to a steady job (as “The Country Boys”) on a local television program.

It was about this time that Roland White was first introduced to the bluegrass music of Bill Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs, and he was immediately captivated: “It really interested me, you know, because we didn’t play that fast,” Roland recalls. “I heard this amazing banjo tune on the radio one morning and I thought, ‘how is he doing that?’ I called the radio station and they told me it was “Dear Old Dixie” by Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. I said, ‘Spell me those last names again’.” Later, Roland found an advertisement in one of the Country Song Roundup magazines for the Jimmie Skinner Record Shop where a person could obtain mail-order bluegrass records. “I noticed they had Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, Reno & Smiley, and Stanley Brothers records, and so every week I ordered something. If you ordered six records you got one free and usually it wasn’t worth a darn but sometimes you got a good one. That’s where we got “Dark Hollow.” And that’s how we got into bluegrass, listening to those records.”

In 1957, banjo player Billy Ray (Latham) joined the three White brothers, and the core of the soon-to-be Kentucky Colonels was established. Clarence sang tenor to Roland’s lead at the time but this was to change for Clarence was barely into his teenage years and his voice soon began to drop. The four of them must have been intensely interested in what they were doing for Roland says they were playing several hours a night, seven days a week: “We just loved to do it. I had all those records coming in and I’d write down new songs and by the end of each night we’d have two or three new songs learned. At one time we could sing anything you wanted. We probably knew 200 songs—all of them bluegrass. It was all interesting to us. Billy Ray had his high voice and we’d do (high-lead) harmonies like the Osborne Brothers.”

At first the group did not play publicly a great deal, but in 1959 they heard about a place in Hollywood called the Ash Grove. Eric Weissberg and the Tarriers had played there some and the group decided to go down and check it out: “We were told there was some weird people down there—beatnicks, you know. We had our instruments with us, so we played during the breaks. Next thing we know, we’re playing regularly at the Ash Grove.”

In 1959 the folk music boom was well under way and the stint at the Ash Grove proved to be a turning point for the young Kentucky Colonels: “All of a sudden we had the chance to play in front of an audience that was there just to listen and that was really unique. We could hear what we were doing and really work on our stuff and get it down good.” Roland had been thinking about making a living at music since his youthful days in Maine (“When I was eleven or twelve someone said, ‘You know, you can make a living at it if you get good enough,’ and I thought, ‘Boy, that’s all right!’”) and now it appeared things were really beginning to happen. The Colonels were playing three or four times a week at colleges and folk festivals, and in 1960 they were hired to do some appearances on the Andy Griffith television show which introduced them for the first time to a national audience.

Then, in 1961, Roland was drafted into the Army, and while he was off in the German hinterlands, 17-year-old Clarence, who to this point had restricted himself, for the most part, to rhythm backup in the band, began to explore the possibilities of the acoustic guitar as a bluegrass lead instrument. There had been some tentative steps made in this direction by other bluegrass musicians —notably, Don Reno; also George Shuffler and Bill Napier with the Stanley Brothers —and Doc Watson was having an impact from outside the bluegrass mainstream, but none of their styles, though interesting in their own right, achieved the dynamic range and excitement of the unique approach to the instrument Clarence would shortly introduce to an unsuspecting bluegrass world. “In about 1959 we got this record of Don Reno playing ‘Country Boy Rock & Roll’ on the guitar,” Roland recalls. “I told Clarence that he ought to learn it. ‘We’ll just sing the song so you can play the break.’ After I left for the Army he really got into playing lead guitar. While I was in the Army the band made the ‘Bluegrass America’ album (now out of print). They sent me a tape and that was the first I heard Clarence do any guitar stuff. It shocked the heck out of me. There was one period after I came out of the Army where we played a lot and he would come up with something different each time. It would be the same song but always something different.”

It was perhaps Clarence White’s unique ability to create tension and excitement in his playing that elevated him to a premier status among bluegrass lead guitarists. His fraught-with-peril, brink-of-disaster lead guitar excursions were at times breathlessly exciting, leaving the listener to wonder at his uncanny abilities. Much of this can be attributed to his unusual mastery of timing and syncopation, but Roland credits it to a more elemental skill—Clarence’s knowledge of simple rhythm. “He had years of just playing rhythm. He knew that real well. I mean real well. That’s where I think people make a mistake. They don’t know good rhythm, and they get into playing a bunch of hot licks. This is true for mandolin, too. That mandolin chop rhythm is real important.” It has been said that Clarence never thought a whole lot of his lead playing, but was quite proud of his rhythm backup. Indeed, in reviewing the Colonels recordings it is evident that much of the rhythmic drive—overdrive might be a better term—of the group can be laid at the doorstep of Clarence’s powerful yet unobtrusive rhythm backup.

Though Clarence’s lead playing is prominent in much of what the Colonels did during this period, it is noticeably absent from the recordings the group made with Scott Stoneman. I asked Roland about this: “We always wanted a real good fiddle player in the band, and he was so good—and such a showman on top of that—that we just all went for it and let him play.” According to Roland, Scott had come out to the west coast for a festival with the entire performing Stoneman family, heard the Colonels play, and asked them for a job. The band admired his playing, and liked him personally, but his drinking problems concerned the group and after some discussion they offered him a job provided he would remain sober. “He said he would do that,” Roland remembers, “and that he would play as long as he could and then leave.”

His six-month stint with the Kentucky Colonels was fortuitous for bluegrass followers affording them some of the few recordings of this extraordinary musician in a bluegrass setting. Though his period with the group was short-lived the surviving recordings provide a valuable insight to the skills and eccentricities of this brilliant musician. Though his unrestrained approach to the instrument sometimes led to a questionable choice of notes, it is possible that no other bluegrass fiddler has played with the same ferocity, inventiveness, and perhaps even technical mastery Scott Stoneman brought to the instrument. And, he could be oh so smooth and soulful when he wanted. Additionally, he had exceptional talents as an entertainer and country-oriented vocalist, and the bluegrass world is the less for his early death in 1973, barely 40 years of age. “One night he said, ‘This is it, boys, I’m leaving and going back east,’” Roland recalls. “He went back east and got to drinking again and his playing slipped a lot, and then of course, he died. It was real sad. He was a real gentleman.”

Though the Kentucky Colonels were at their peak in the mid 1960s, the bluegrass music scene was not, the popularity of the Beatles having superseded the folk revival of the earlier part of the decade. As such, the Colonels fortunes began to nosedive, and personal appearances got farther and farther apart. “About 1966 we got into playing more country (style) places,” Roland says. “We even got electric instruments and a drummer. Clarence got an electric guitar. He’d been listening to (guitarist) James Burton, whom he admired, and we played a lot of lounges doing whatever was popular—Buck Owens, George Jones, Eddy Arnold and others. After a while we disbanded, but James Burton had heard Clarence play and got him some session work. Meanwhile, Bill Monroe came to the west coast on a tour and asked me to play guitar with him and go back to Tennessee. The next thing I knew I was on the bus with a borrowed guitar. About three or four months later I decided to stay and sent for my wife.”

Roland’s relocation to Nashville turned out to be permanent and he still resides there. At the time, though, musical jobs were scarce—even for Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys—but Roland stayed with him until late 1968. He had been anxious to get back to the mandolin and noticed that Flatt & Scruggs weren’t carrying a mandolin player in their band. “I went to WSM where I knew Lester would be (for the Flatt & Scruggs radio show) and told him I’d be leaving Bill by the end of the year. I told him if he could use a mandolin player and half-way tenor singer I’d like the job. He said, ‘I don’t like to be hiring off of Monroe.’ I told him that I had turned in my notice to Bill, and he said, ‘Well, there’s going to be a lot happening next year—there’s going to be some changes.’ I had no idea what he meant. In late January of the next year, after I got back from a tour of Europe with Bill, Lester called and wanted to know if I was still interested in a job. He had just split with Scruggs. I went over to Uncle Josh’s (Graves) house for a practice and (banjo player) Vic Jordan, who was also with Monroe, drove up behind me. He looked at me, and I looked at him, and I said, ‘What are you doing here?’ He said, ‘Well, I might get a job with Lester.’ I said, ‘That’s what I’m here for —Is Monroe ever gonna be mad!’ Anyway, we played the Opry that weekend and I stayed with Lester until 1973.”

According to Roland, this was a very difficult time for Lester Flatt. His twenty-three year association with Earl Scruggs had come to an unceremonious end when Lester called it quits after a show on the Opry. He had become increasingly dissatisfied with the direction the band was taking. At the urging of Earl, his wife Louise (who helped to manage the group), and their producer, Lester was being asked to perform more and more material—Bob Dylan, and other modern songs—that was not suited to him nor to his liking. “Earl was having some physical problems, too, that affected their stage shows,” Roland recalls, “and Lester felt, even though they were selling a lot of records, that they shouldn’t do any more of that material. Lester was really hurt that Earl had let it go so far that it got to the point where he had to just walk off. His best friend was Earl Scruggs.”

In spite of these setbacks to his career, Lester still retained the services of fiddler Paul Warren, Dobroist Josh Graves, and bassist Jake Tullock in his reformed band now called “Lester Flatt and the Nashville Grass.” With the addition of Roland White and Vic Jordan the potential was there for some excellent bluegrass but it was not to be—at least on the first albums the group released. “It was the same old problem, in a way,” Roland believes. “There were no rehearsals and you’d go into the studio and do one, maybe two, takes and then leave and someone else would mix the album. Lester wasn’t in control. He didn’t have anything more to do with it. I don’t think he knew who to go to for the mixing. I think Earl had some say in the Flatt and Scruggs albums. Lester never did. He was never asked and didn’t know anything about it.”

For Roland this somewhat trying period in Nashville was nevertheless fruitful in many ways. He had always spent a good deal of time studying and learning from other musicians and now he had the opportunity to observe closely the playing of such bluegrass stalwarts as Monroe, Flatt, Paul Warren, Jake Tullock, and Josh Graves. “It was totally different being around those great players,” Roland remembers. There were hours and hours spent taping radio shows and the Martha White television show. I was listening to Paul doing his backup stuff, and Josh—I learned a lot from those guys. It was like Scott Stoneman. I learned a lot of stuff on the mandolin from listening to his fiddling.

At this time I didn’t listen to other mandolin players because I’d already listened to them all. I was doing some of the nice little things on the mandolin that people like Bobby Osborne and Bill Monroe did. But now what I was doing was to play stuff I’d heard off other instruments. I always really liked Ralph Mooney’s pedal steel when he played with Wynn Stewart. I like Dobro and I listened a lot to Josh.”

Meanwhile, back in California, Clarence White had begun playing with the Byrds. He had gotten regular session work but then the opportunity to join the well-known rock and roll band had come along: “He didn’t want to give up the session work,” Roland believes, “but the Byrds had lost some popularity and they felt that he could help them a whole lot. They offered him good money so he went ahead with it. He was glad he did but a lot of problems (of the life style) came with it. He liked the music—the opportunity to do something different—and still do quite a bit of session work.”

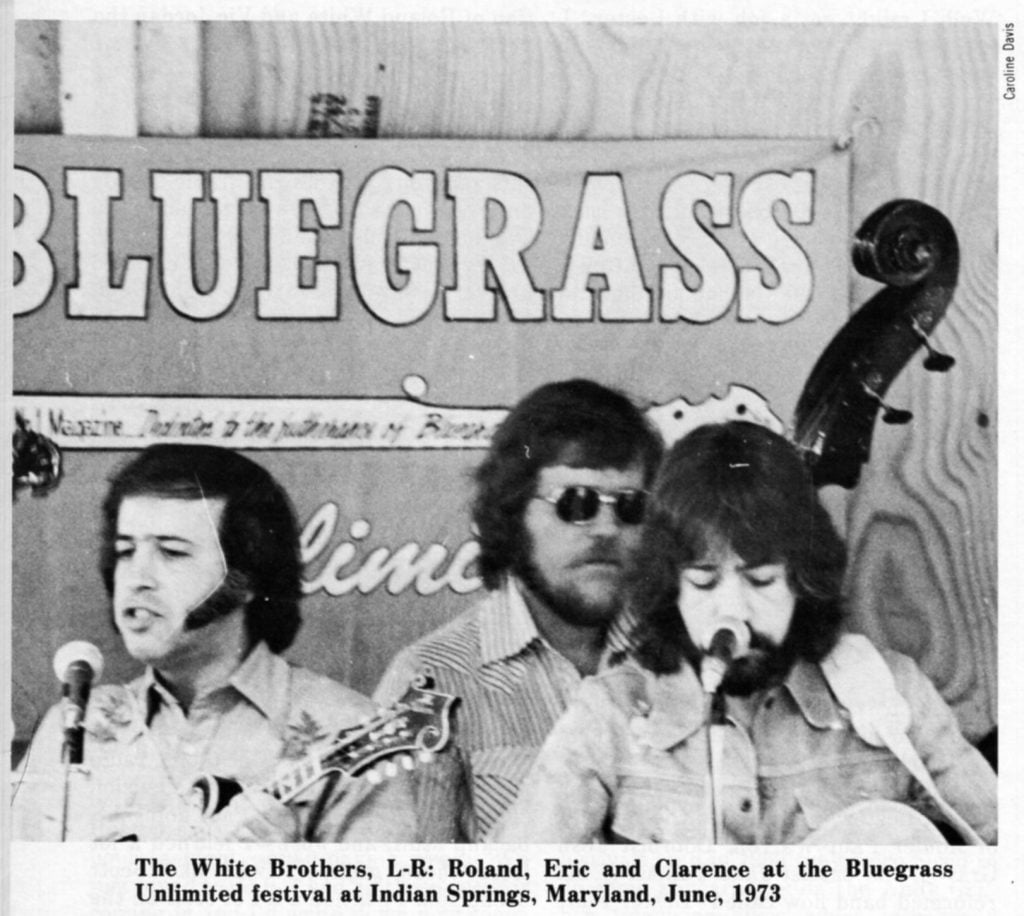

In the early 1970s the bluegrass scene started to pick up again, and Roland and Clarence began playing some jobs together. There was a tour of Sweden in early 1973 with Alan Munde on banjo, but any hopes of a long-term reunion were shattered with Clarence’s tragic death, at 29, in a Palmdale, California automobile mishap in which Roland was seriously injured.

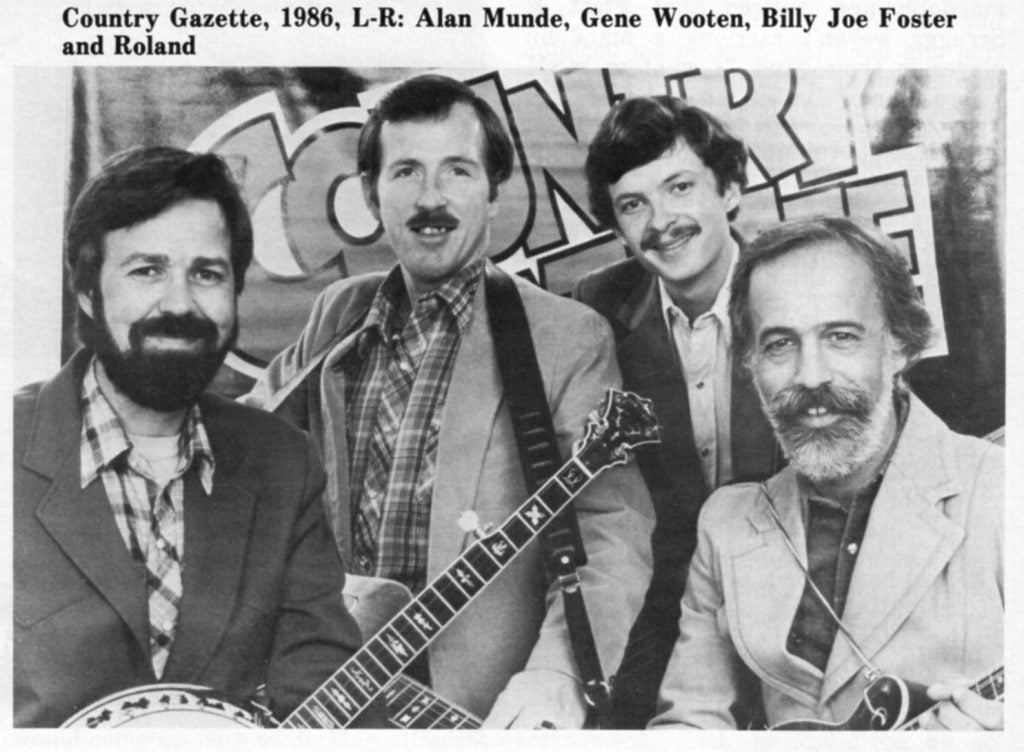

Roland feels that Clarence would probably be playing some sort of country music if he had lived, but he is not certain of this: “It’s really hard to say. Clarence didn’t know how things were going to turn out musically. He’d done that Muleskinner (album) stuff (with Pete Rowan, Richard Greene, Bill Keith, and David Grisman) and he kind of liked that. He was pretty much open to anything. It was a hard blow to lose him—hard to believe it could happen. The Country Gazette offered me a job about that time and if it hadn’t of been for that I don’t know what I would have done. We did some east coast tours and went to Europe and that saved me.”

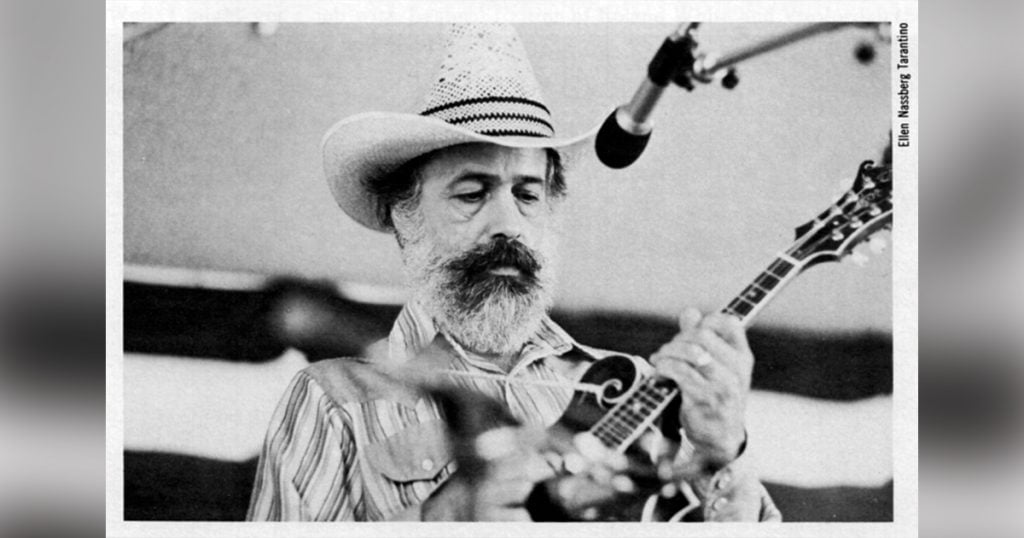

Today, at 47 years of age, Roland White continues his life-long obsession with bluegrass music and remains a vital member of the Country Gazette. He has nearly thirty years in now as a professional musician and shows no sign of any loss of interest: “I really enjoy what I’m doing now. I enjoy working with Alan (Munde). I’ve learned a lot from him. He’s a good musician and a good person. We (the Kentucky Colonels) realized way back that we had something of our own —that we weren’t really working for anyone else, just basically doing our own thing. Working for Bill and Lester was good but working for someone else is not the way to do it. If you can have your own little group and do what you want to do —it’s a lot easier.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

See his BU podcast from 1982 https://bluegrassunlimited.com/podcasts/ for more details about his early years and the incident leading to Clarence’s death.