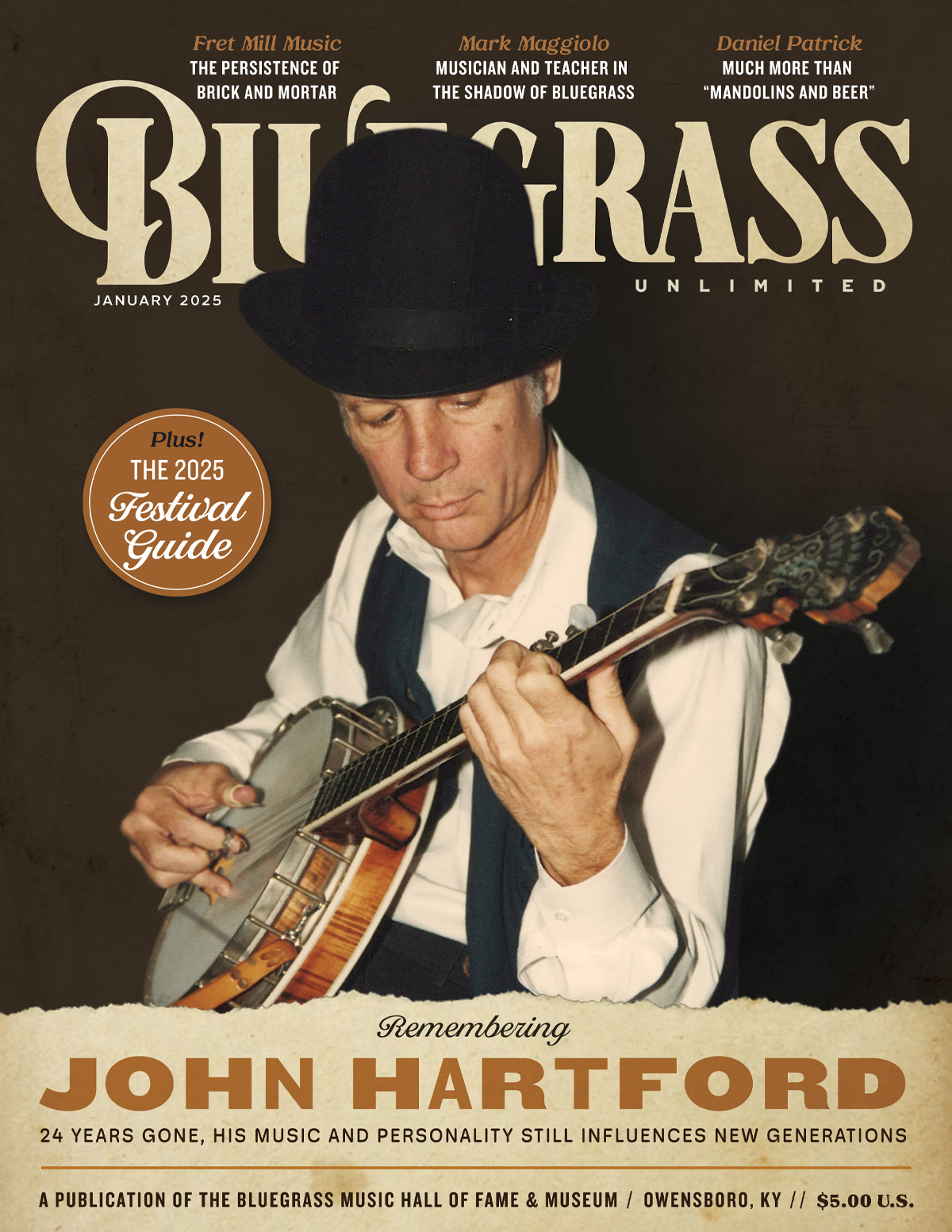

Home > Articles > The Tradition > Remembering John Hartford

Remembering John Hartford

Hartford is 24 Years Gone, Yet His Music and Personality Still Influences New Generations

I got to know John Hartford a little bit through the sheer luck of geography. As a native of Huntington, West Virginia, located on the banks of the mighty Ohio River, my family would eventually move to Cincinnati when I was six years old, which is a bigger city also founded within that same watershed.

One of the positives about living in the Ohio River Valley during the last century was being able to witness the big riverboats come into port when they still roamed the larger tributaries of the Mississippi River. One such magnificent vessel was the wooden sternwheel steamboat called the Delta Queen, which was based in Cincinnati for many years.

I bring all of this up because John Hartford, one of our great and truly unique roots music artists, was also a lover of riverboats. He grew up not far from the Mississippi River near St. Louis and he became fascinated with life on a paddle boat at a young age. He was equally fascinated with American roots music, and as he pursued both paths in his life, it would lead to him becoming a licensed steamboat pilot, and a member of the IBMA Bluegrass Hall of Fame.

When I was in my late teens in the early 1980s, I visited the aforementioned Delta Queen one day when it docked in the Port of Cincinnati and that is when a young man walked up to me and asked me if I was interested in taking his job on the boat. He explained that he could not quit his job as a dishwasher on the vessel unless he found somebody in one of the ports to replace him, and said I would have my own small room on the boat. But, the catch was that if I was interested in making this life-changing move, I’d have to go home and pack up my clothes and belongings and be back on the riverboat and ready to shove off in two hours’ time.

I had a job at that point in my life and I was about to start college, so I turned him down. I am about 80% sure that I made the right decision, but that other 20% has intrigued me ever since then, and I often wonder what advice John Hartford would have given me if he had been standing there beside me, or looking down and talking to me from the upper deck.

When it comes to the music side of Hartford’s life, I first became intrigued with his talent at a young age when I watched him perform on national TV. That was especially true when he sang his hit song “Gentle On My Mind” with Glen Campbell on Campbell’s Goodtime Hour television show. Even though I was only ten years old or so, I was not only fascinated with playing of musical instruments in general, I was also captivated by the poetry of the lyrics of that song in particular.

I was into the rock and soul music of that time period, and went down every rabbit hole of every new genre and sub-genre that bubbled up in the late 1960s and early 70s, without a doubt. And yet, one of the things I learned at that young age was that great lyrics were great lyrics. I was transforming from a kid who had fun listening to, Honey, Oh, sugar, sugar, you are my candy girl, and you got me wanting you, and When you’re hot, you’re hot, and when you’re not, you’re not, to appreciating, It’s knowing that your door is always open, and your path is free to walk, that makes me tend to leave my sleeping bag, rolled up, and stashed behind your couch.

When it came to “Gentle On My Mind,” when Hartford or Campbell sang the words, I dip my cup of soup back, from a gurglin’ cracklin’ cauldron in some train yard, my beard, a roughening’ coal pile, and a dirty hat pulled low across my face, I believed it. My grandpa was a coal minor, and I knew what a slag heap coal pile was, and that imagery clicked with me.

When I got older and knew more about the ways of love, this line fascinated me as well, It’s not clinging to the rocks and ivy, planted on their columns now that bind me, or something that somebody said, because they thought we fit together walking. How many times do couples fit together walking, but then the connection ends when they either go their separate ways, or folks try to bring them together in the first place because of that perceived connection? It was a lot for an inexperienced and naïve mind to ponder.

The point of all of this was that those two aspects of John Hartford’s life, the riverboats and the music, both came together in one event when my city of Cincinnati hosted the first-ever Tall Stacks Steamboat and Music Festival in 1988.

When that inaugural year of Tall Stacks unfolded, it was magic. Eventually, most of the riverboats that existed on American waters that could get to Ohio did so, and the sight of those 20-plus riverboats in one place was captivating.

There were many musical acts that performed during that first Tall Stacks, and the highlight for me was the multiple shows that Hartford did as a solo artist during the day. Those performances all led up to the nighttime headlining shows, which incredibly included the aforementioned Glen Campbell. During that performance, as we all hoped, Hartford appeared and they two of them sang “Gentle On My Mind” like they did 20 years earlier.

The Tall Stacks events would happen every three years after the first one, and that is how I got to know Hartford just a little bit. We both had a few of the same eclectic interests in some ways, and I wasn’t afraid to approach him and have a real conversation with him. I say that because a lot of folks I have talked to over the years, even professional musicians, were in awe of him and nervous about engaging him.

I became truly aware of that phenomenon when I stood off to the side of the stage after one of his performances at Tall Stacks in 1988 and waited for those in line to get his autograph and do their meet-and-greets.

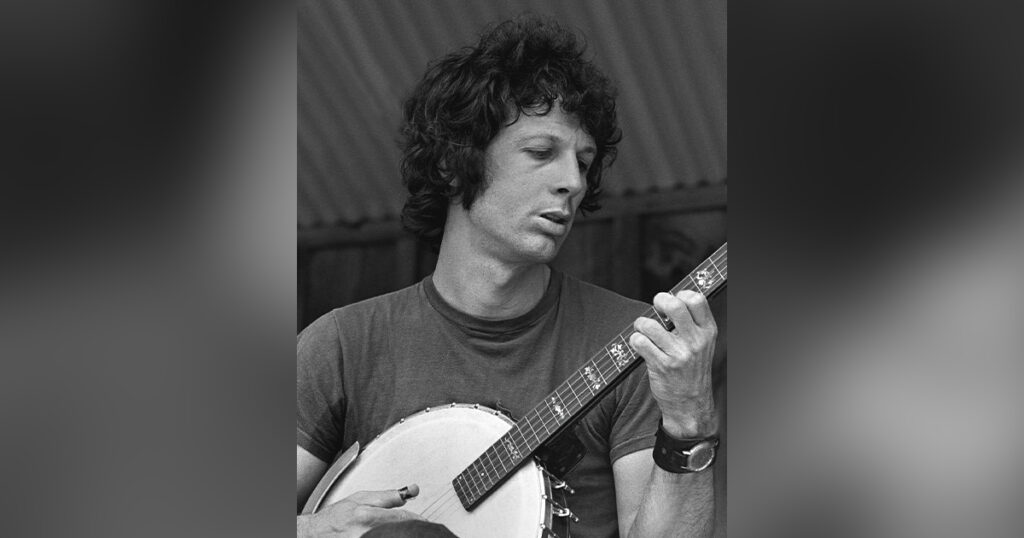

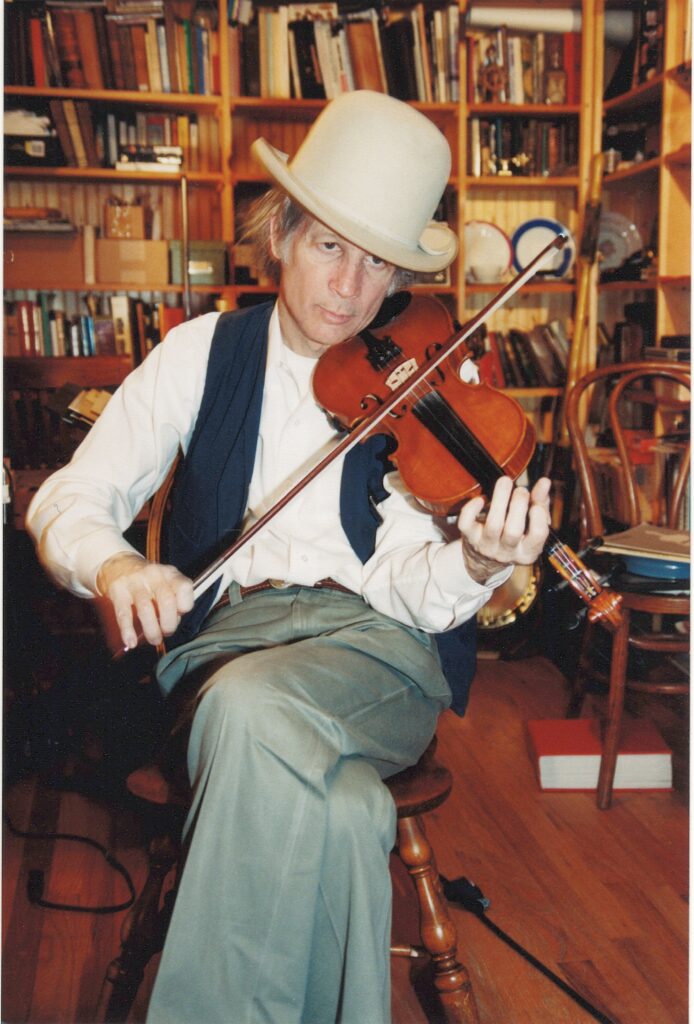

When Hartford did his solo show, it was just him up on the stage with his instruments and his 4-by-4 piece of plywood with an expertly-placed microphone on it. With a little sand thrown on the platform for sound effects reasons, Hartford would play the fiddle or the banjo while at the same time keeping rhythm with his feet shuffling on the board.

As he played on the open-air stages on the riverbank, the steamboats would be floating upstream and downstream in the background behind him. When he would stop playing for a second and turn and wave to the boats, the captains and pilots, most of whom he had known for years, would see him and recognize him and would blow their steam whistles in response and it was marvelous.

Hartford’s one-man show was in the tradition of all the old traveling minstrels and musicians that played the river ports of this country for hundreds of years. And, if you squinted your eyes as you soaked up the whole event that surrounded you and used your imagination on those October days and nights, all of those things combined to create the closest thing to time travel that you could ever hope to experience. It was a brief glimpse into life in the 1800s.

I was standing off to the side after Hartford’s show that I mentioned above when I overheard some of the ladies talking as they stood in line, waiting to meet him. They were amazed at how he could dance and shuffle his feet to the rhythm on the plywood for such a long time, while simultaneously playing his instruments and singing. When it was their turn to approach Hartford for an autograph, they became too shy to ask him about his foot work. That is when I decided to bring their question up for them, asking him about his dancing prowess as his fans quietly stood in front of him as he signed his name on their paper. It was then that I walked right into the dry and wry sense of humor that was John Hartford.

“So John,” I said, “How is it that you keep your legs up like that?” “Well,” he answered, without missing a beat, “They’re attached to my hips, I reckon.”

Recently, while searching amongst some old digital files I had collected from the early days of personal computing, I came across some audio that I recorded from that first 1988 Tall Stacks Festival. I had not paid much attention to the files because they were recorded at too fast of a speed.

In 1988, I wanted to capture the sounds of the event, so on the second day, I brought and carried around a big and bulky cassette boombox about a foot-and-a-half wide that had a ‘Record’ button on it and cheap external microphones on the front of it. I carried that heavy piece of machinery around with me the whole day.

Unfortunately, the batteries that were used to run the cumbersome cassette player began to run out of steam. That meant that the sounds were being recorded at a slower speed than normal. When that happens and you play the cassette tape back on a player that is spinning at the right speed, everything sounds sped up.

When I found the sound files a few months ago, however, it dawned on me that in these modern times, I could digitally adjust the speed and revive that moment captured in time and play it at the speed it was meant to be in.

As the restored audio begins, which I have uploaded onto YouTube under the name ‘John Hartford at the 1988 Tall Stacks Steamboat and Music Festival,’ the first sound you hear is of one of the steamboats on the water.

As I walked along with the record button set to the ‘on’ position on that day 36 years ago, I also picked up the lively conversations of my brother Doug, my Uncle Wayne ‘Wormy’ Smith, and his girlfriend Sandra, soon being reminded that all three of them have passed away since then.

Then, further into the tape, there is the sound of John Hartford performing his solo act, shuffling his feet like crazy while playing a version of his classic 1971 tune “Steam Powered Areo-Plain.” About two minutes into this rendition, you hear the loud boom of a cannon going off, done every half hour by some of the 1880s-era re-enactors.

As Hartford finishes “Steam,” he turns around on the stage to look towards the Ohio River and six seconds later he says, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the Belle of Louisville. Give them a big hand…along with Captain Mike Fitzgerald.” Amazingly, Captain Fitzgerald is still in the lead chair on the Belle of Louisville as the 1914-built steamboat still cruises the Ohio River every summer and fall.

Later, on the cassette tape, Hartford starts into a high-tempo version of “Skippin’ In The Mississippi Dew.” With his fiddle and bow in his hands and his shoes shuffling double time on the sandy board, he begins to sing the lyrics Well I dream of a girl and a steering wheel steamboat, a pilothouse stove and engine room brass, Hanging on a post by the main deck stairway, Long hair skippin’ in the Mississippi dew. Just as his vocals begin, one of the larger steamboats on the river behind him with a very loud whistle lets it rip, and the sound of it is way louder than Hartford’s PA speakers.

Without missing a beat, as he keeps his foot rhythm steady, Hartford waits for the four successive fog horn blasts to end and with perfect timing, as the audience laughs with him about this wonderfully unusual interruption; he kicks back into the lyrics with a growl singing, Oh the river runs wide, runs deep, runs muddy, the river runs long after I am gone, With the steamboat wheeling on a big wide bend, just skippin’ in the Mississippi dew.

My first thoughts as I listen to this recording almost four decades in the future are similar to how I felt back then, as in, ‘Where the heck do you experience such an amazing atmosphere like this?” The answer, of course, is that it happened in every port along the Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio Rivers during the 1800s when steamboats were king.

The next time I saw John, it was at the next Tall Stacks Steamboat and Music celebration three years later. I ran into him while he was sitting out a steady rain in a vehicle with Cincinnati-based musician Katie Laur, who was a bluegrass legend in her own right.

Hartford recognized me after a few quick seconds of conversation and they invited me into the car to converse and wait out the rain. I eventually gave him a cassette tape I had mixed for him of unusual music I had collected over the years. The playlist included gems from Lillie Mae and the Dixie Gospel-Aires, Floyd Tillman, the song “Five and Dime” from an obscure 1975 album by Mose McCormack, which I still love to this day, and other cool stuff.

On the next day, after the rain brought in a brutal October cold front with it, I saw Katie and John at the outdoor stage where banjo legend J.D. Crowe was performing. It was about 40 degrees that day and Crowe and the boys were performing on an outdoor stage with no source of heat to speak of, which can be rough for a musician when it comes to getting their frigid fingers to work right in such conditions. When J.D. asks the audience that if they have any requests, Hartford, realizing the stiff-fingers situation the band was in, disguises his voice and yells out “Train 45,” knowing that it is one of the hardest and fastest bluegrass songs you could ever lean a five-string into, even in warm weather.

Hartford starts laughing when he sees Crowe’s band get a collective frown on their face after his request, as they look at each other and look at their hands and instruments. After a few seconds, Crowe looks out into the crowd saying, “Hartford is that you?” J.D. finally figured out what was up. John was laughing hard, but J.D. and his band played the tune anyway, just to prove they could do it.

The last time I saw John was in 1999 at what would be his last Tall Stacks Festival. It was obvious that John’s health was not in a good place as his Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma had taken its toll over the previous 20 years and it was finally wearing him down. After his show, he greeted the audience, but only from a distance as he could not shake anyone’s hand at this point and risk infection.

Before I went to see him on the banks of the mighty Ohio River that day, I found a country cookbook written by Ronni Lundy of Louisville, Kentucky. Titled Shuck Beans, Stack Cakes, and Honest Fried Chicken, there was a picture in the book of Hartford taken back in 1958. I wanted to show it to him and he got a big kick out of it, as back in the late 1950s, his hair was slicked down, he had a tie on, and he recognized an old girlfriend that was also in the photo.

When I walked away from him that day, I had a bad feeling about his future. It’s amazing how things can change someone for the worse from one time to the next. He kept on playing until April of 2001 when in Texas, in the middle of a run of shows, and with his long-time band and the group Nickel Creek helping him out; he lost control of his hands. John Hartford would die in June of that year. He was only 63 years old. Six months later, his wife Marie would pass away on his birthday, December 30, 2001.

After Hartford’s death on June 4, 2001, an amazing thing happened. On his web site, johnhartford.com, which he originally wanted to name “Delusions of Banjer,” a message board was created for people to share their stories about him, and over 2,000 posts soon appeared. There were postings coming in from Germany, Italy, Brazil, New Zealand, Netherlands, Bolivia, Canada, and all of the U.S. The stories shared there were touching, unusual, and blatantly Hartford-goofy.

One recurring story that appeared was about the time that Hartford performed at the Skyline Music Festival in Ronceverte, West Virginia, in 1977. During that event, some idiot burned down the barn that housed all of the generators that supplied the electricity that ran the stages. According to attendees Jan Worthington and Austin Troxell, after it got dark, John sent word out to the festival goers to come to the main stage and bring their camping lanterns with them. With hundreds of flickering lights creating an awesome glow, everyone apparently witnessed as good and unique a show by John Hartford as they could ever want to see.

According to other posters, especially those that met him by accident or at unusual times, it was a memorable experience for many. In one posted example, there were some folks that were catfishing on the Cumberland River when Hartford pulled over to walk down the bank to watch the General Lee riverboat go by, only to hang for a bit with his new fishermen buddies, He would often come up with odd quips that people remembered. In this case, he told them that a poor man’s BLT sandwich was taking white bread, covering it with mayonnaise, and putting regular Dorito chips in the middle.

Even near the end of his life, Hartford never lost his sense of humor. The long-running, West Virginia-based radio show Mountain Stage wanted to do a tribute for him while he was still able to participate, and many great musicians came out to perform an array of his songs. The concert was released as an album soon after.

At the end of the show, Hartford came out to play a short set. He started by talking to the audience and the other musicians onstage, saying, “If I’m going to be true to form, I got to tell you like it is. I know why everybody’s here. They think I’m going to croak.”

Hartford went on to say that if he was going to do his part, then he should die within about three weeks so it would still be fresh in everyone’s mind. The problem with that was, as he put it, “We got the whole month of October booked.”

After Hartford passed away, many looked at the lyrics of his song “Old Time River Man” in a different light, wondering if he would live those words out with his spirit one night when no one was looking.

Where does an old time riverman go, after he’s passed away? Does his soul still keep watch on the deep, for the rest of the river day? Does he then come back as a channel cat, or the wasps that light on the wheel? Or the birds that fly in the summer sky, or the fish swimming under the keel?

My article on the death of John Hartford came out in June of 2001, thanks to the late Michael Buffalo Smith, the Editor of Gritz Music magazine. It was my first piece that was published after I decided to finally take up music journalism as my profession. Since then, I have had the pleasure of asking many amazing musicians about their thoughts on Hartford’s music, and his influence on the roots music industry. It doesn’t happen as much as it used to, as he has been dead for almost 24 years now. But, there is something about Hartford’s originality that causes new generations to go down that path.

Luckily, for the first ten to fifteen years or so after his passing, the John Hartford stories just kept on coming. All of the following interviews were done by yours truly, and they reveal a lot about Hartford’s career, talents and personality. He wasn’t perfect, as he could be a bit narcissistic, eccentric and cantankerous at times by some accounts. That is not unusual for artists whose name in on the marquee and who are paying the bills and running the band, etc. But, he could also be unselfish and one of the coolest cats that you could ever want to meet, to the point of being a true and positive influence on many people.

I mentioned Katie Laur earlier and a couple of years after Hartford left this world, she gave me some insight into how hard they would play music together back in the day.

“In 1975, I met John Hartford and I went on this bluegrass cruise with him and about 14 other musicians,” said Laur. “We flew over to St. Louis and took the Delta Queen riverboat back to Cincinnati. We played 24/7. I remember Doug Dillard was playing banjo on the trip and his fingers would swell up so bad he couldn’t get the picks off of them. So, we would say, well, if you can’t get the picks off you might as well play some more, and that is what we did. We stayed up all night playing music, and the passengers who got up in the morning to eat breakfast thought we had gotten up early just to play with them.”

Katie Laur passed away earlier this year on August 2, 2024, at 83 years of age. She was known as one of the first female musician to lead a bluegrass band filled with men with whom she was neither related to or in a relationship with, which was not an easy task in the 1970s.

For many wonderful years, the John Hartford Stringband consisted of Mike Compton on mandolin, Chris Sharp on guitar, Matt Combs on fiddle, Bob Carlin on the banjo, and Mark Schatz on bass, with Larry Perkins being a part of the group’s earlier versions.

A decade after Hartford’s death, his Stringband recorded a tribute album called Memories of John that was fabulous and featured guests such as Alison Brown, Bela Fleck, Tim O’Brien, Alan O’Bryant, Eilee Carson Shatz and more.

As for the current younger generation, Tray Wellington recorded a version of “Half Past Four” on his album Black Banjo in a nod to past great musicians. The tune was written by the acclaimed 1900s West Virginia fiddler Ed Haley and made popular by Hartford, who loved the music of Haley, and even spent a lot of money and time researching Haley’s life. Haley died in 1951.

“I love John Hartford,” said Wellington. “I love John Hartford’s music because I think he was a very different kind of artist that touched on a lot of things. In his own life, I think he was a true artist that did 100% his own style, and I think that is a really cool thing to hear. He did whatever he wanted to do, and yet it was undeniable that he had his own sound, no matter what he did. I’ve listened to him for such a long time that I can’t remember where or how I first heard him. Although, I do remember listening to his classic album Aereo-Plain for the first time and I think that is what turned me on to his music. It’s a great recording.”

The late and legendary songwriter and singer Gordon Lightfoot talked to me about spending time with Hartford back in 2010—“I heard John Hartford play many songs,” Lightfoot said. “The one that I remember best is the one he played when he was opening for us for a while, which was ‘Good Old Howard Hughes and All of His Blues.’ It was a song that he played on the banjo. A favorite memory of John was when we were walking out in a field in Oklahoma on this beautiful farm one night. The sky was just ablaze with stars, and John and I and my lead guitar player were walking out into this great big pasture at one o’clock in the morning.”

An amazing thing happened when the John Hartford’s Mammoth Collection of Fiddle Tunes book was released a few years ago, as it was discovered that many of Hartford’s never-before-seen compositions found in his personal archives were named after people he had met over the years. One example is the fiddle tune “Laura Boo,” named after Western North Carolina musician Laura Boosinger, who is the voice of the Blue Ridge Music Trails of North Carolina organization.

“A couple of years ago, I was at the IBMA bluegrass convention in Raleigh when I received a Facebook message from John’s daughter Katie Harford Hogue, saying, ‘I think this is for you,’” said Boosinger. “Attached was a copy of the tune ‘Laura Boo,’ written in John’s handwriting from his notebook. I couldn’t have been more surprised or honored or humbled. John liked a song I had recorded, a Carter Family number called ‘When the Roses Bloom in Dixieland.’ He would ask me to join him and sing the song with him any time I ran into him at a show. Eventually, he recorded it and gave me a big shout out on the album. Maybe it was during this time when he wrote the fiddle tune ‘Laura Boo.’”

Boosinger played with Hartford at his second to last-ever concert, which took place in Asheville in April of 2001.

“Even though he was very ill, and he had to keep his fans at an arms distance due to his weak immune system and he never really played or sang a note, he still entertained his audience,” said Boosinger. “He asked me to come up and sing ‘When the Roses Bloom in Dixieland’ with him. He managed to play a note or two on the banjo and sing harmony with me as we shared a chair. I will never forget it. Then, David Holt and I went to visit John in May when it was clear that his time was running out. Matt Combs was there, John’s agent Keith Case was there, as was Vassar Clements and Earl and Louise Scruggs. We all sat on the side porch near the Cumberland River and visited. It was very old-school and Southern, and a nice afternoon visit. John told me that when he died, I should stand at the head of the coffin and sing ‘When the Roses Bloom in Dixieland.’ He said, ‘If I don’t raise up, you can close the lid.’”

Another artist who was stunned to find his name on a John Hartford fiddle tune was Pennsylvania musician Ted The Fiddler.

“John Hartford was my friend and mentor for some 28 years or more,” Ted said. “One day, I got a note from John’s daughter Katie. She’d found some things that she thought I might want to have, and one of them was a fiddle tune named after me with a date on it that read March 24, 1987. I was blown away. That was the date that he first invited me up on stage with him at a small festival in Allentown, Pa.”

Ted The Fiddler also got to experience Hartford’s love of all things riverboats one day while visiting him at his home outside of Nashville.

“John used to have these three-day birthday party jam sessions around Christmas and New Year’s Eve and one of the first times I made it down there for one of those events, it was unusually warm for December,” said Ted. “I had never seen a steamboat close up before and the General Jackson was rolling down the Cumberland River right by his house. I climbed down the embankment to the shore to watch it go by while a make-shift band up on the porch played John’s ‘General Jackson Theme.’ As I stood there in awe as the boat went by, I heard this deep voice beside me telling me about the cubic feet and water displacement of the boat. John also told me about Captain Poe, who was waving to us from the massive boat’s Pilot House as he blew the steamboat whistle. John, standing there right next to me, was just as excited as I was, taking in the whole experience. John told me all about steamboats and riverboat life as we watched it go by. As the General Jackson approached the turn in the river, John said, ‘It’s bad luck to watch a steamboat go ‘round the bend.’ So, we turned around and went back up to the house.”

Hartford’s Aereo-Plain album, released in 1971, would go on to influence multiple generations of open-minded musicians. Produced by David Bromberg and featuring Randy Scruggs on bass, the album showcased the genius of the Dobrolic Plectoral Society, which consisted of Hartford, Norman Blake, Tut Taylor and Vassar Clements.

Now, with Hartford passing away in 2001, Clements dying in 2005, and Taylor’s death in 2015, Blake became the last man standing.

“I find it kind of strange, in a way, to be the last person of that group,” said Blake. “John and I were about the same age, so John went prematurely. John and I were less than a year different in age, I think. But, Tut was 91 and Vassar was ten years older than me. So yes, I feel rather strange to be the last man. But, I know that the Aereo-Plain album has become a significant factor (in the music world).”

The roots of Hartford’s move towards recording the Aereo-Plain album started when he was still involved with the world of TV networks in Los Angeles. According to one newspaper article written in the early 1970s, Hartford was offered a role as a detective in a new television series. But, with his song “Gentle On My Mind” not only being a hit on the charts, but also becoming one of the top five most recorded songs in history, he soon realized that he had enough royalty money from song to be able to pursue his own path in music.

“John had a band at that time called Iron Mountain Depot, which included a drummer and a guitar player whose name I believe was Terry Paul, who played a 12-string Ovation guitar,” said Blake. “John did a television special out on the West Coast. Bill Carruthers, who was the man that was producing the Johnny Cash Show at first, was doing this special with Hartford and he decided that I should be involved in that, so he took me out there to play with an orchestra on that show. I got to jamming around and playing with John at that point, and then John came back to Nashville and we’d play for fun around the house. Tut, George Gruhn, Randy Wood and myself all hung around together then.

“Then, John decided that he was going to change his whole thing,” continues Blake. “He was the clean-cut Glen Campbell guy before that, and then he became the John Hartford of the Aereo-Plain era. He got rid of that band that he had at the time and he hired me to work with him and play guitar. I left Kris Kristofferson to work with him. I wanted to get back into something more traditionally-related, so I took the job with John and was living in Nashville. Then, the next thing I knew, he hired Tut and he hired Vassar Clements and then we had the Aereo-Plain band.”

Blake was not really aware of how special the group was at the time, at least in an historical context.

“Well, we were thankful to get a good-paying job,” said Blake. “We knew it was different. We had never played with anyone exactly like John. He formed that group and then he brought David Bromberg down from up in New York to produce that album over at the Glaser Brothers sound studio and it went from there. When John brought David down to do it, he just thought that it would be good to have someone with an outside influence. John left him alone. Of course, John left us all alone. His whole credo in playing music, including on that recording, was we never verbalized anything. He never told us how to play a thing. He’d just start playing and say, ‘You guys fall in and play what you feel like playing.’ We didn’t listen to playbacks. We would cut and cut and cut, but we didn’t hear them back until later on. We would cut for several hours or wait until the next day before we would listen to anything. That is the way John played music with us. Everybody had artistic freedom, as he put it.”

Unfortunately, in the music business, all good things must often come to an end. The Aereo-Plain band disbanded a little over a year after it came together.

“That part of it was financially motivated,” said Blake. “It was not making money. You know how those things go. He was paying us decent and he was keeping it on the road and there were airplane flights and the whole scenario, but it was not financially profitable. So, I stayed on with John for a while after the band dissolved, and he kept me on as an accompanist. Then it got to where he wanted to do his thing, strictly just him, and that is when I went out on my own.”

Leftover Salmon’s Vince Herman remembers a wonderful time spent just feet away from Hartford one night when he reunited with a former band mate of his legendary Aereo-Plain group. It happened in the state of Idaho.

“I got to hang with John Hartford and probably my favorite time with him was when we played a festival up in Idaho and Vassar Clements was there, playing with another band,” says Herman. “We left the festival and went back to the hotel and there sitting in the lobby was Vassar and John and a mandolin player I didn’t know, but he knew them both and knew all of their stuff. John and Vassar sat in that lobby for three-and-a-half hours with those matching fiddles of theirs and played. I know a lot of fiddle tunes, yet I knew maybe a quarter of the tunes in those three-and-a-half hours of playing. They dug so deep into the song cannon. I so wish I had recorded that session. It was incredible.

“There were probably 20 musicians sitting in that room, but there was just one guy playing a mandolin, giving them a chop,” continues Herman. “It was more than perfect with just Vassar and John and somebody chopping behind them. Nobody else wanted to put themselves into an equation like that. They seemed to have a huge pile of tunes that they had shared together over the years that they dug back for. They were playing fiddle tunes in the key of F and E-sharp. You know what I mean? They were really out there. They were doing the Ed Haley longbow stuff and some Texas Shorty stuff. They were playing old time and bluegrass, and the lines aren’t so clear between those two genres when it is just fiddles playing. So much is lost with the passing of those two men in terms of tunes, knowledge of the styles, where they came from and who played what. There was so much history in the minds of those two guys and it was great to see the depth of that in that session. The thought of it makes me miss them both.”

Chris Thile, who has dazzled audiences and fellow musicians alike with his time as a member of Nickel Creek, with the Punch Brothers, or playing solo while interpreting Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas with his mandolin, is considered one of the true geniuses of American roots music. In fact, Thile won the MacArthur Foundation Genius honor back in 2012.

Fortunately, Thile also got to spend some time with Hartford in his younger years.

“John taught me so many things,” said Thile. “He would say, ‘Hey man, don’t crack your fingers.’ ‘Practice with the metronome.’ ‘Play in time.’ ‘Play the melody.’ He learned how to write music late and he had started to collect old fiddle tunes. John also loved Bach’s ‘Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin.’ It was John Hartford who told me to get Henryk Szeryng’s version of ‘Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin.’ I listened to those recordings, top to bottom, so many times. The next time I saw him I said, ‘John, I’ve been listening to ‘Sonatas and Partitas.’ I’m trying to play them like Szeryng right now.’ And he was like, ‘I have to hear it. I really want to hear it. Play me one of them.’ So, I played him the E major Prelude and he was just all over it.”

One day at the annual MerleFest music festival in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, Thile spent a magical evening with Hartford at a restaurant. As the two musicians had dinner together, a musical challenge was proffered that resulted in a simple piece of paper that has been saved for the ages.

“One night, we were at the Sagebrush Steakhouse outside of MerleFest and there was a big, giant group of us all around one big table,” said Thile. “John and I sat together. He got one of his little note cards out, one of his three-by-five cards, and all of a sudden he was quiet for a while. I was sitting next to him, talking to Natalie McMaster or somebody like that, and he started writing. All of a sudden, he handed the piece of paper to me and he said, ‘You can read music, right?’ ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘I just wrote a ‘first part.’ You write the second part, and it will be our new tune called ‘The Sagebrush Gathering.’ So, I sat there and wrote a second part down, put the ‘repeat’ signs in, and he signed it in his beautiful calligraphy script. He gave me that three-by-five card of that little tune we wrote together, and I still have it in my office. No one has ever played it.”

Happily, the great Peter Rowan got his flowers while he was still breathing when he was inducted into the IBMA Hall of Fame in 2022. When I asked him about what was one of the best off-stage jams that he was ever a part of, his thoughts went immediately back to the aforementioned Tall Stacks Steamboat and Music Festival. This particular jam happened at someone’s house, and it involved John Hartford and the Tex-Mex accordion legend Flaco Jiminez,

“I knew John Hartford in a certain way,” says Rowan. “It was ‘John and I,’ and I went out on the river with him one time. He reminded me of Jerry Garcia in that the immediate line was, ‘It’s wide open, anything can happen and it could be dangerous.’”

Over the years, Rowan spent more time with Jimenez, however, recording and touring with the Tex-Mex legend many times.

“Flaco Jimenez was basically the sound of the Free Mexican Airforce as it existed on my first Flying Fish (label) record,” says Rowan. “It was suggested that I go and record this stuff down in Texas, so I found Flaco and we hung out. I went to the places he was playing and Flaco is unbelievable. He’ll just stay up and talk and play. I’ve stayed up all night with him. We toured over in Scotland for a while and in Edinburgh we played all night and he took on all comers. Some guy would want to play a song at the party and Flaco was eager.

“There is a big stone mountain right there in Edinburgh called Arthur’s Seat,” continues Rowan. “It had a big rock outcropping and I remember that we saw the sunrise with our instruments up on Arthur’s Seat. That was a memory. Flaco is standing there, and he always wore this nice woolen poncho which was all-weather gear, and there is Flaco at sunrise on Arthur’s Seat standing up there and playing some unbelievably beautiful morning song that probably goes back a long time. That was something.”

So, as this Jam Story begins, all three musicians, Rowan, Hartford and Jimenez, found themselves in an impromptu jam session during the Tall Stacks Festival that would turn into an offstage musical tour-de-force.

“One year at Tall Stacks, I backed Benny Martin up and I guess I did a solo show, maybe,” remembers Rowan. “It was great to hang with Benny. And, one of my other duties was to be a guest on Flaco Jimenez’s set. So, we went to a party afterwards and at this party were myself, Roy Husky, a couple of members of Flaco’s band, John Hartford and a bunch of other people. I think Katie Laur was there as well. Hartford was an unstoppable force of nature and he would go into some old Missouri clog dance. Well, Flaco picks up his accordion and he is kind of going right along with it. John finishes his part, and Flaco jumps in with a variation of the tune with some German-Spanish tradition from Texas on it, and it was like, ‘Uh oh! Whoa!’”

Rowan knew that something special was brewing, so he grabbed his axe.

“I had my mandolin out and I was kind of chunking along,” says Rowan. “And then, Flaco goes into a hornpipe, and then John jumps into it and plays the hornpipe, playing it similar and even different on the fiddle. John didn’t play any banjo. He just played fiddle the whole night. This went on for about four or five hours. Then, Flaco would play some incredibly sentimental Spanish waltz, then Hartford would come in with something like ‘The Missouri Waltz.’ Then Hartford would start some other tune and Flaco would follow him with another tune. I’m telling you, man, that was the best jam session I ever heard because it reminded me of some of the best old bluegrass sessions where you get a room full of people like Benny Martin and a guy like Tut Taylor and a guy like Kenny Baker. It only takes a little bit of that chemistry to make the sparks fly. And, those guys would do that same thing. They would follow each other, especially if you’ve got fiddlers.”

Remembering the positive aspects of the Hartford-Jimenez session sparks Rowan into talking about similar yet rare jams that he has experienced in the bluegrass world.

“When the fiddle players are there, like Red Taylor and guys like that who know that stuff, they go from one song to another without blinking an eye and that’s when it is fun to be a bluegrass guitarist, truthfully,” says Rowan. “That is where it is really fun, just flipping the right stuff behind the fiddle players and going from one tune to another. The only people that have made that a professional thing are the Irish where they do what is called a ‘set,’ where there’d be a reel and a hornpipe and a jig. A ‘set of reels,’ which is like three reels in a row, they still do that.

“I have to say, I’m just an amateur, really,” continues Rowan. “I’d rather be in a room with those classic fiddle players than do anything else I can imagine. When those guys would lead the jams, it would be like a pyramid with the very top like a sparkling crystal jewel and we’d be the rhythm section underneath just going along with it and making it happen. But I can count with the fingers on one hand those times that I was a part of anything like that. So, that night at Tall Stacks, really, truly and honestly, I would have to say was the epitome. There was John Hartford from Missouri and there was Flaco Jimenez from San Antonio, Texas, trading off without ever hesitating, without ever saying ‘Oh, you know that?’ or ‘That’s interesting.’ Nobody said a thing. It was ‘in the moment, on we go,’ and I couldn’t tell you the names of those tunes. It was just magic.”

At the 2003 Tall Stacks Festival, that first one to take place after Hartford’s death, the event organizers honored John Hartford by dedicating the festival to him and putting up round historical markers on the grounds that told his life story. One morning during the festival, I read an article in the local newspaper about a group of 52 5th-graders from Clermont Northeastern Middle School, located in nearby Adams County in southern Ohio, that were going to perform a play based on the book written by Hartford called Steamboat In A Cornfield.

The book was based on a true story about the USS Virginia, a steamboat that traversed the inner waterways of the U.S. that tried to make it to a safe port during a flood in the 1800’s. The captain made a wrong turn and ended up bottoming out in a cornfield. After the flood waters receded, the boat was stuck there in that cornfield for six months and it became quite the attraction.

As I stood there and watched the play, and the kid actors were great, enthusiastic and adorable as they read their lines. And yes, there were a ton of proud parents there video-taping the show in that age just before smartphones would make their appearance.

The play was a hoot and the kid actors ended their performance by singing “Old Man River.” But then, it dawned on me that there was not a single John Hartford song in the play. After the show was over, I talked to the teacher in charge and asked her why there were no John Hartford songs in the production. To my surprise, she said that even though they had performed the play for years, they did not know until a month earlier that Hartford, the book’s author, was also a very famous musician.

“We went and got a tape recently,” she said. These wonderful folks from a rural area out in the Ohio countryside came to John Hartford strictly because someone found his book about a steamboat in a corn field. As I walked away, I laughed to myself while thing about the smile on Hartford’s face had he heard this story. I’m guessing that his first response would have not been about his music not being played that day, but instead he would have been thrilled that attention was brought to the age of the steamboats through his book, which was written for kids, and brought to life by kids at the Tall Stacks Festival.

Finally, back in 1999 when I saw Hartford in person for the last time ever, he gave me a gift that would play out four years later. When I last talked to Hartford that sunny day, I brought one of Vassar Clement’s solo albums that he recorded on Mercury Records in 1975. The cover of the vinyl album featured a picture of Vassar playing the fiddle, with just his face and his fiddle taking up the whole cover.

The project had an all-star cast of musicians playing on it including John, so I asked him to sign the album. Hartford looked at Vassar’s big head on the cover, paused, and then he laughed and then proceeded to write his autograph big as can be right across Vassar’s forehead using his well-practiced calligraphy style of writing that Thile mentions above.

After Hartford died in 2001, I ran into Vassar backstage at FloydFest in 2003 and told him the story. Knowing Vassar would be there, I brought that album and Hartford’s autograph on his forehead and showed it to him. Vassar just laughed out loud, and said, “Old Hartford got one on me again.”