Home > Articles > The Archives > Ralph Rinzler

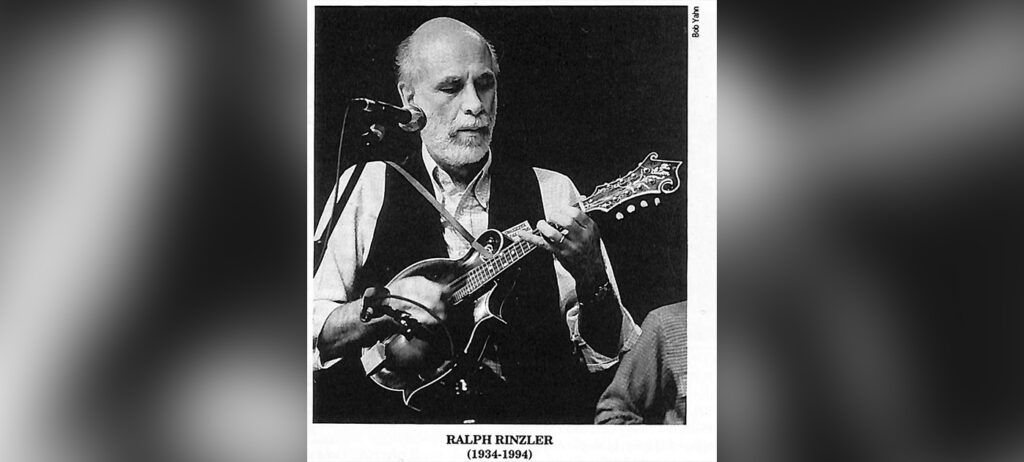

Ralph Rinzler

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1994, Volume 29, Number 2

Ralph Rinzler—one of the most influential figures in bluegrass, folk and old-time country music history—died on July 2,1994, at his home in Washington, D.C., after a lengthy illness. He was 59 years old.

During an active life as a folklorist, promoter and musician, Rinzler revitalized the career of Bill Monroe, discovered Doc Watson, helped develop the bluegrass festival as we know it today, and introduced traditional-style country music to vast new audiences.

Born in 1934 in Passiac, N.J., Rinzler was fascinated as a boy by a set of Library of Congress folk songs recordings given him as a gift. At Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania (from which he graduated in 1956), he became part of the active campus folk scene which included a well-established annual festival. Rinzler later noted, “If I was ever prepared by my work at college to do anything in life, it was in seeing what possibilities a festival had for human learning and communication.”

Rinzler went on to study with prominent folklorists A.L. Lloyd and Alan Lomax. He took a sincere interest in the music of the south, and in the 1950s and ’60s was one of few northerners seeking out bluegrass and old-time music on its home ground.

On a song-collecting trip to North Carolina in 1961 for Folkways Records (during which he recorded Clarence Ashley, Fred Price and Clint Howard), Rinzler was introduced to a blind guitarist who played electrified country music for profit and traditional music for fun—Arthel “Doc” Watson. Ralph convinced Doc there was an appreciative national audience for the old sounds and got him bookings on the folk music circuit. The rest is history.

Rinzler first heard Bill Monroe at the New River Ranch in Maryland in 1954. He immediately recognized that compared to other bluegrass performers Monroe “was in a category all his own…He was playing music that was a lot more sophisticated and archaic. At the same time, it was both modern and ancient.”

It seems difficult to imagine now, but at the time Monroe (although a respected Grand Ole Opry veteran with a loyal following) had become something of a footnote to country music history as the former employer of Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. After winning the trust of the taciturn Monroe, Rinzler documented his accomplishments as the true founder of bluegrass in a landmark 1963 Sing Out! magazine article. He became Monroe’s manager and introduced him to new audiences by arranging bookings at major folk festivals and persuading Decca Records to release collections of important Monroe recordings with extensive liner notes.

From 1964 to 1967, Rinzler served as a director of the influential Newport (Rhode Island) Folk Festival. When country music promoter Carlton Haney conceived of an all-bluegrass weekend to be built around reunions of classic Blue Grass Boys bands, he closely studied the Newport format of concerts and educational workshops. Rinzler helped organize Haney’s 1965 show in Fincastle, Va., which ushered in the era of bluegrass festivals as we know them today.

Unlike armchair interpreters of folk arts, Ralph Rinzler was a skilled and seasoned performer of the music he loved. As a college student, he taught himself guitar, banjo and mandolin, and appeared occasionally on bass with the Blue Grass Boys while managing Monroe. He appeared for several years as mandolinist/ vocalist of the New York-based Greenbriar Boys, one of the first successful “city-billy” bands. The group won the old-time division at the 1959 Union Grove Fiddler’s Convention, backed Joan Baez on tour and recorded several well-received albums for Vanguard. (Rinzler later recalled with a smile the time the Greenbriar Boys headlined a show at the Gerde’s Folk City club; the opening act that night—making his New York, debut—was an unknown singer/songwriter named Bob Dylan.)

David Grisman and a number of now-prominent northern-born pickers were encouraged by Rinzler in their early efforts to learn how to play. Rinzler typically depreciated his own excellent picking and singing, taking greater satisfaction in using his music to spread the word about Monroe, Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers, Clarence Ashley and other great “originals.” Indeed, many northerners first saw “bluegrass” used to describe a form of music in Rinzler’s finer notes for the 1957 Folkways collection American Banjo Scruggs-Style (re-released as Smithsonian/Folk- ways SF 40037).

Ralph Rinzler went on to a distinguished career at the Smithsonian Institution. In 1967, he became founder and director of the Smithsonian’s Festival of American Folklife on the capital mall, an annual event from which evolved the Smithsonian’s Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies. (Rinzler died during this year’s festival and the gathering immediately became a memorial to his life.)

He was promoted in 1983 to the museum’s Assistant Secretary for Public Service and is credited with introducing CD-ROM technology to the institution. In 1987, he facilitated the acquisition of the immense (and immensely important) Folkways Records Catalog & Archives. A multi-artist tribute album Folkways: A Vision Shared (Columbia 44034), in whose production Rinzler was actively involved, won a 1988 Grammy. He became an assistant secretary emeritus of the Smithsonian in 1990.

Rinzler helped promote a diverse range of folk arts. He was particularly interested in the preservation of pottery making and other traditional crafts. He worked for several years with the United nations’ UNESCO cultural agency and served recently on a White House task force on music and education.

One of Rinzler’s last major contributions to bluegrass music came as executive producer of collections of rare five recordings by Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys (Smithsonian/Folk- ways SF 40063) and Monroe with Doc Watson (SF 40064). He also helped facilitate the recent joint production by Smithsonian/Folkways and Homespun Video of instructional tapes by Monroe (Homespun VD-MON-MN01 & MN02) and Watson (VD-DOC-GT010). At the time of his death he was working with long-time friend Mike Seeger on an expansion of Harry Smith’s major 1952 reference work The Anthology Of American Folk Music.

In the classic movie It’s A Wonderful Life, a man is shown how much happiness others enjoy because he was born. Although we might take certain things for granted today, it is largely due to Rinzler’s efforts that Bill Monroe has received full credit for the creation of bluegrass; that the virtuoso Watson-style school of flatpicking has developed; that folk festivals enrich the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans; and that bluegrass and old-time music delight millions more around the world.

Ralph Rinzler indeed had a wonderful life. He is survived by his wife Kathryn Hughes Rinzler, a stepdaughter Mami and, in a real sense, by all of us who are the better that he lived.