Home > Articles > The Artists > Putting the I in IBMA

Putting the I in IBMA

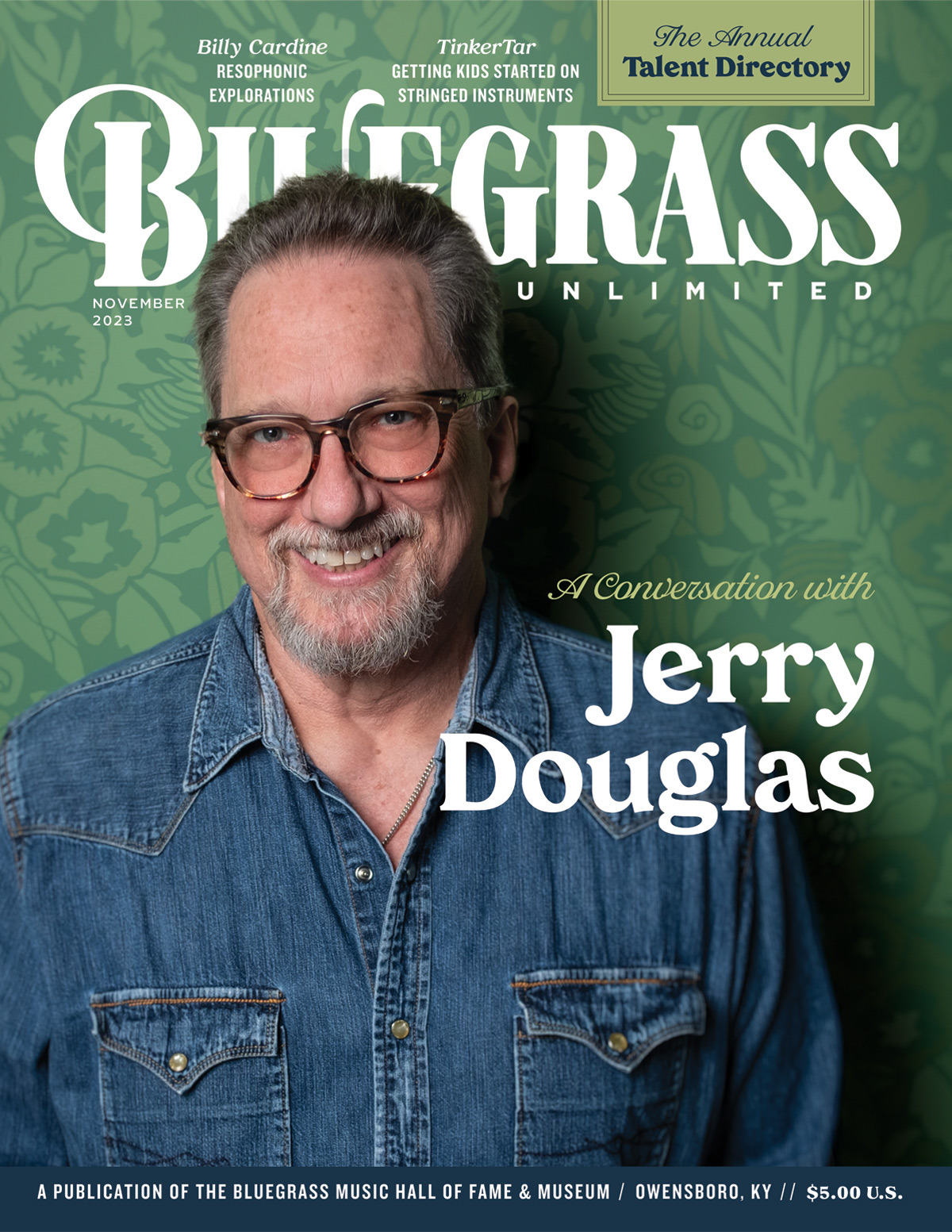

Photos by Ben Wright

With the release of their latest album Lead and Iron and after more than nineteen years as a band, Chicago-based Henhouse Prowlers has settled on the right combination. They started as a six-piece band playing every Tuesday night at a neighborhood bar on the north side of Chicago. As they started to tour, playing a few hours outside of town, the band naturally evolved. As they grew more serious about performing, members who did not have the desire or time to tour moved away from the band. Founding members Ben Wright and Jon Goldfine were joined by Chris Dollar about five and half years ago and Jake Howard two years later.

Lead and Iron, their tenth album and the first produced by Stephen Mougin at Dark Shadow Recording, marks what Wright calls “a huge step up quality-wise.” He said for their last studio album the four of them had gone into the studio “doing the best we could amongst the four of us.” He said he is still proud of that album, but “this album, with Mojo’s help, feels like a huge step in a positive direction—both songwriting and musically.”

They connected with Mougin two years ago at IBMA. Mougin and Ned Luberecki approached the band after they played a show and started a conversation about their moving to a record label, a discussion that continued for about eight months before they struck a deal. The band had self-released up to that point and wanted to be sure of the direction. Even more, said Wright, “We have a lot of facets to what we do as a band, one of the biggest being our nonprofit Bluegrass Ambassadors.” The fit, they discovered, was natural. He noted that Mougin’s wife Jana, also a singer, is from Slovakia. “They loved what we do; it wouldn’t have worked if they hadn’t,” he said.

In 2022, Henhouse Prowlers and Dark Shadow Recording paired up at IBMA to host a suite in the Marriott, which, they noted, “solidified everything.” Wright said the band went into the project thinking, “Geez, we hope we all made the right decision” and left thinking, “Oh my God! These guys are our partners!” The collaboration, they noted, felt so symbiotic.

The band considers their position as Bluegrass Ambassadors a defining role for the band. Ben noted, “Early on, as we started to tour more, we had an appetite to get outside of the country. That slowly started to happen, and people caught on to the fact that we really enjoy the things that come with being in a band, especially the opportunity to meet people from different states, but then also different countries.” Someone told them about a program called American Music Abroad. They applied, were accepted, and in 2013 started building a relationship with the State Department, which runs the program, to do cultural diplomacy programming, a role that suited them perfectly.

The American Music Abroad program, going on for 70 or 80 years now, uses music as a way to connect people. As Wright noted, diplomats can seem stuffy, but every culture has music. “When you put musicians together from different countries, they can connect in ways that stuffy diplomats can’t.” The members of Henhouse Prowlers were so inspired by the program that they decided to do as much of it as they could on their own. They next turned their music and experiences into educational programs both at home and abroad.

Wright noted that during COVID they were able to get some support from Shure microphones to make an album of nine songs from nine different countries. Because of their nonprofit status, they were able to pay a group of artists from all over the world during the pandemic.

Wright said, “We put together that album, and we’re really proud of it. We sing in the original languages, and it’s an extension of what we do on stage.

As Bluegrass Ambassadors, Wright said, “Alongside our own original material, we also share music at every show from our travels and use it as an opportunity to tell people about different places we’ve been and the wonderful people we’ve met.”

Asked why bluegrass translates so well in other countries, Dollar remarked, “You know, bluegrass on its own doesn’t necessarily connect with everyone. That’s why we learn their tunes and show them what bluegrass would sound like if we were playing their songs. That helps because sometimes when we go to a country, we’ll start playing fast bluegrass that we love, and they don’t know how to dance to it.”

Howard pointed out that every country has its own traditional music, so they are able to bring traditional American music to share, and the people they visit can do the same with their own traditional music. He added, “When we do those trips, we usually have bands from that region play with us as well, so we may have ninety minutes to get to know these guys. We don’t speak a word of their language, they don’t speak English, but we share music, and we’re able to connect through that. We take some of their influences, and they take some influences that we have and make something work.”

Goldfine pointed out that common themes in bluegrass are found in folk music from other countries: “There are so many songs about love and loss and longing for home and those themes resonate.

Ben added, “Honestly, the core of what we’ve learned and what we believe is that we can’t just go to these places and say, ‘Here’s bluegrass music. You’d better love it.’ We listen before we go, and we learn music so we don’t start off on that foot. It’s more like ‘Hey, we’ve taken time to learn about your music and culture; maybe you’re more likely to listen to ours now because we’ve made that first step.’”

Those commonalities—love, loss, family, and home—have shaped some of the themes the band members write about. Wright said, “We’re all big advocates of travel and experiencing other people and how they live around the world. It foundationally changes how we see things, so we think a little bit deeper and more introspectively now with our songwriting simply because of those experiences that we’ve had. We recognize that there are things that we fundamentally share as human beings, no matter how different we look or where we’re from. Something shifts in your brain, and you feel more like a global citizen instead of somebody from Chicago. I look back at our material on our earlier albums before that started happening, and it’s just not quite as interesting.”

The new album shows signs of maturity as well. The songs chosen for the album, for example, speak of their experience on the road—“Rolling Wheels” and “My Last Run,” and especially the first track on the new album “Home For,” which ends with a reference to a baby on the way. The baby, now here, is Dollar’s son, the first child born to a member of the band. Dollar explained, “It’s always been about finding a balance. When a child comes along, it can throw off your balance, so it’s taken a lot of adapting.” He noted, however, that his bandmates have been extremely supportive of his family decisions, which he considers a blessing.

The one instrumental track on the album “Wobbly Dog” also pays homage to the band’s soft spot—for their dogs. Howard, who composed that song, said the past year had been tough. “Three of the four of us lost an animal, which is heartbreaking, but the beautiful thing about this group is that we’re best friends, so when something happens, we’re all there to support each other. Not every band can say that.” He added that they might poke fun at each other “but not for crying about a dog.”

The band released four singles from the album before its release, beginning with “My Little Flower.” Released last, the title track “Lead and Iron” was written in response to the all-too-frequent school shootings and what seems like the futility of prayers to change things. The band had a heightened awareness of timing of its release, not wanting to “piggyback” off anyone’s grief.

Howard said, “It’s really hard to find the right time to release something like that and to have it out in the world. I wrote it for a specific purpose, but it has meaning in a lot of other certain circumstances that we find ourselves in in life. The song isn’t supposed to be overtly political at all,” he said, “but sometimes change has to happen. It’s supposed to help.”

Another powerful song on the album, “Died Before Their Time,” left nothing to inference. The song makes direct references to the consequences of the abuse of power, ranging from Nathan Forrest and the origin of the Klan to the Khmer Rouge killing fields, and Charles Taylor’s reign of terror in Liberia.

Goldfine said the song started with a more generic message, but when the band members gathered with Mougin to start writing the song, there were “unfortunately, a lot of different people that could be the subject of verses for that song.”

Wright said, “I haven’t thought until [now] about how our music’s been influenced by our travels, but that song references somebody that we would have never really known about. When we were in Liberia, we stood on the roof of this hotel that had machine gun holes in the walls from when Charles Taylor took over that hotel and it became his base. Marrio stood on the beach where he executed everybody, and we learned so much about it that left a profound mark on us.” Ironically, he noted, people in the U.S. have to dig to find information about this event in recent history. “It really does speak to a lot of things that are important to us,” he added.

Goldfine added, “Other verses are reference to places we stood as well, like the one in Cambodia. I went to the to the killing fields memorial and to the to prison camp that had been a school and is now a memorial museum. In Rwanda, we went to a church where mass murders had happened during the genocide there, so the song is about places we went and have close feelings about.”

The band also brings their outreach to schools and festivals, where they share music.

Wright said, “It’s become a huge part of what we do. It really does balance out the performance side. We’re at the point now where we feel like we have to do a school program at least three or four times a year to feel balanced. We’re not just playing shows and trying to run the business, but giving back to kids because we all remember moments that changed our lives. That’s a huge part of bluegrass, honestly, passing on the knowledge to the next generation. It got passed on to us, and it’s our turn to pass it on to the next generation.

He said the band members are uniquely suited for working with children: “Most importantly, we’re all a bunch of children still.” He said the band doesn’t have trouble tailoring their program to whatever age group they are working with. “It’s not hard for us to act like a bunch of 4th graders.”

While they may not feel much older than fourth graders, the band has made some adjustments in their travel in recent years. While they used to log 175 shows a year—sometimes hitting over 200—they now play between 75 and 100 shows, recognizing the stress on home life and families.

Wright admits that there was a time when their philosophy was “If you can’t keep up with the band schedule, you shouldn’t be in the band.” Wright said that now that Chris Dollar is a father—and every member of the band is a core member—he has realized, “It’s okay to change your philosophy as a business for the right people. I would have been mad at myself for saying that ten years ago, but I’m proud of saying it now. A lot of that rests on Chris.”

The balance role of the band members is also evident on the new album, where they switch off lead and harmony vocals. Dollar explained, “We definitely cater our sets to make sure that at least within the first six songs, you’ll hear one from each of us. We’re all songwriters, and we all have a flow of songs coming in, so we can keep it balanced.”

Starting with at least twenty-five new songs, the band worked together to pare down to the track list that found a place on the new album. Mougin weighed in as well, paring down the list down to about fifteen songs before band members made suggestions, though they admitted they promoted each other’s songs. While they admit it’s hard to narrow down the theme of the album, it might be, said Wright, “This is who we are right now.”

After their album release on September 15 at Nashville’s iconic Station Inn, they headed back to Raleigh for IBMA week, where they again partnered with Dark Shadow Recording for a suite at the Marriott. Their Tuesday night showcase highlighted international bands from Slovakia, Canada, Australia, South Korea, Norway, and Wales.

Wright said, “We are advocates through Bluegrass Ambassadors, focusing more on the I in IBMA. The organization is doing a wonderful job with that right now.” The band just returned from France where they conducted a camp with 100 students from across Europe who are “as passionate about bluegrass as anybody you’d meet in the United States,” he added. “It’s time to shift our focus over there and recognize that bluegrass is growing internationally. That’s important to us because we’ve been inspired by musicians we’ve met over there. Some of the best musicians we’ve ever met come from the Czech Republic, and everybody needs to know that. It only benefits bluegrasses as a whole to acknowledge that, underline it, and focus on it.”

With the release of Lead and Iron, the Henhouse Prowlers will draw on their personal and musical harmony as they aim for balance, especially with “so much more to be home for.”