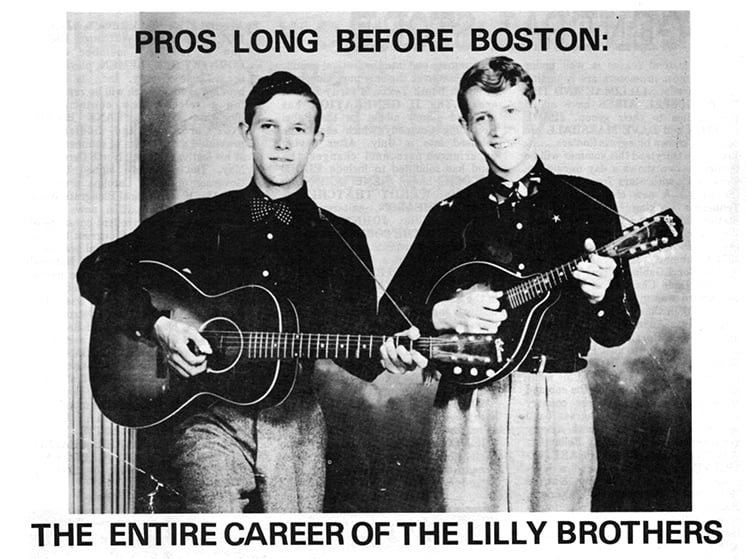

Home > Articles > The Archives > Pros Long Before Boston: The Entire Career of the Lilly Brothers

Pros Long Before Boston: The Entire Career of the Lilly Brothers

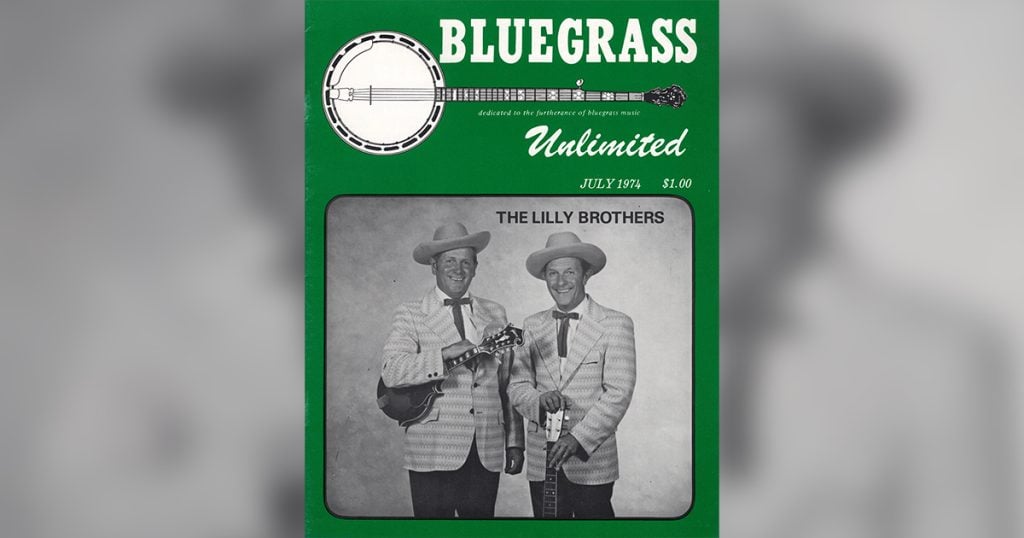

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July 1974, Volume 9, Number 1

One of the reasons that old-time and bluegrass music attracted a wide audience among urban college youth of the east was the long presence of the Lilly Brothers and Don Stover in the Boston area. Through their nightly appearances at Hillbilly Ranch and their pioneering concerts at the University of Chicago Folk Festival, Harvard University and other schools in the northeast, the Lillys were influential in acquainting urban youth with Appalachian vocal and instrumental styles. Because of this long sojourn in New England, the Lillys’ career is often considered to have been primarily concentrated in Boston and at Hillbilly Ranch. The prime purpose of this article is to place the activities of Bea and Everett Lilly in a broader perspective and to remind bluegrass fans that when they first went to Massachusetts they were not at their beginning, but had already experienced more than a decade as seasoned professionals.

Clear Creek, West Virginia is a rural community located in Raleigh County, about midway between Charleston and Bluefield. About fifteen miles away is Beckley, the county seat and an important center for live country music on radio during the 1940’s. The Lilly family is one of the largest in West Virginia, being descended from one Robert Lilly, an associate of Lord Baltimore who came to Maryland about 1640. The Lilly Reunion held in Flat Top Mountain during the 1930’s and 1940’s was an affair which attracted crowds in excess of 75,000, a figure comparable with those at the largest festivals of our own time. Old-time music fans may recall Roy Harvey’s recording “The Lilly Reunion” which described the first of these events. A few years later Everett and Bea were among those who entertained their numerous kinfolk and other visitors.

Mr. and Mrs. Burt Lilly of Clear Creek were the parents of seven children, including Mitchell Burt Lilly (called Bea or B. from his middle initial), born on December 15, 1921, and Charles Everett Lilly (name recorded on birth certificate as Charly Edwin) on July 1, 1924. Farming was the prime occupation of the Lilly family although coal mines were in the area and both brothers worked for a time in the mines. Church gatherings, prayer meetings and revivals provided not only spiritual comfort but also served as one of the few social activities. The isolation of the rural life helped to make the local people create their own entertainment. Music was an important part of the local religious scene and it was here that Everett and Bea heard their first music outside the family home. By 1933 when Bea was twelve, he was playing the guitar and both he and his younger brother were singing.

In those early years the public performances of the Lilly Brothers were limited to the Clear Creak vicinity, but nonetheless they managed to make themselves heard. Everett recalls that on occasions they would go from house to house and do their singing for one or two families at a time. They also sang at churches and other such local events as weddings and funerals. Their first “professional” job was at a movie theater in Ameagle. a company town, some eight miles from Clear Creek.

By the 1935-1936 period, the Lilly Brothers began to be more influenced by professional groups outside their local area. Although they were already familiar with the better known country groups such as the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, the appearance of the brother duet groups in the mid-thirties had a more direct impression on their style. The groups which featured mandolin and guitar made the deepest impact. Homer and Walter Callahan were the first such group to record extensively beginning in 1934, although they first used two guitars on their recordings. In 1936, both the Monroe Brothers and Blue Sky Boys (Bill and Earl Bolick) also began to record extensively even though the former were already well known through their radio work. Bill and Charlie Monroe undoubtedly had the most direct influence on the development of the Lilly style with livelier vocals and more complex instrumentation, but the Callahans were their early favorites. Everett described the early Monroe music as “get up and go…lively” while the subdued approach of the Bolicks is referred to as “livin’ room” music. Guitar duet groups such as the Delmores, Dixons, and Sheltons, along with string bands like the Mainers had a lesser impact upon Everett and Bea’s style.

As a result of the popularity of the mandolin-guitar brother duets, Everett took up the mandolin and it always has been his major instrument although he is also adept on fiddle and plays “drop thumb” or clawhammer banjo and on rare occasions, guitar. By about 1939, their radio career began on the local station WJLS, Beckley, then in its broad casting infancy.

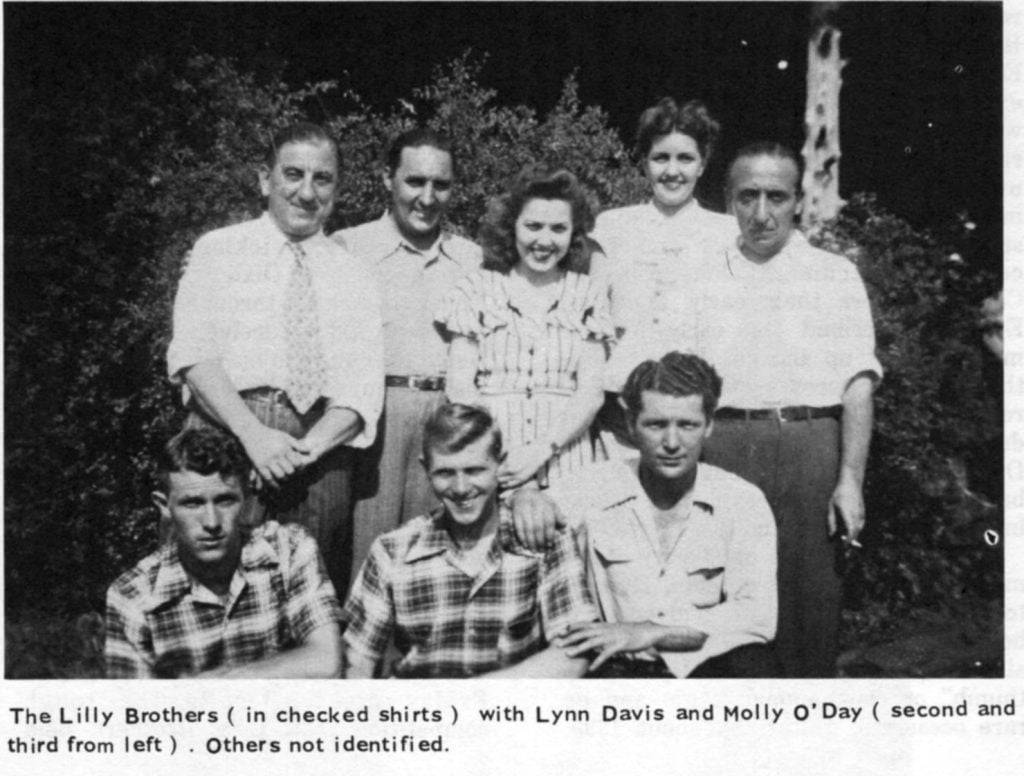

Shortly after, Everett and Bea through the assistance of a neighbor began playing on the Old Farm Hour at WCHS in Charleston. Although this show is only a memory today, both it and daily programs on the same station are among the forgotten great disseminators of early country music. Several important artists and groups either began or spent a major part of their careers in Charleston. Probably the most popular locally was the team of Cap, Andy and Flip, composed of Warren Caplinger, Andrew Patterson and William Strickland. Billy Cox, known as the Dixie Songbird, was Charleston based throughout his career and recorded extensively for both the Gennett and Columbia labels. Two of his many compositions that have become standard are “Filipino Baby” and “Sparklin’ Brown Eyes.” The Buskirk Family worked there too and so for a time did Buddy Starcher, T. Texas Tyler, Natchee the Indian, Molly O’Day and Lynn Davis. Frank (Uncle Si) Welling, who had been half of the recording team of Welling and McGhee, was director of the Old Farm Hour which was performed before a live audience on Friday night. Despite the tough competition, the Lilly Brothers held their own as a popular act during their sojourn on the show. For a time, they were known as the Lonesome Holler Boys, but throughout their career, they always maintained their identity as the Lilly Brothers, even when they were part of another group.

Back in Beckley, WJLS was becoming a more important station on the country scene. The Lilly Brothers also worked there for quite a while with Molly O’Day and Lynn Davis. This was in the period before Molly had become the living legend of country music that she is today through her classic recordings on Columbia. Although Molly and Lynn headed the group, the Lilly Brothers retained their identity by performing part of the show as a brother duet team. Another member of the act was Charles Elzie, known as Kentucky Slim, the Little Darling, whom many bluegrass fans will remember for his comedy work with Flatt and Scruggs and Hylo Brown during the middle and late 1950’s. The group played almost nightly personal appearances in the mountain communities of southern West Virginia and Everett recalls the many hours spent in Lynn’s 1941 Ford, including one time when he dozed off while driving and ran the car over a curb in some small town without even waking the others. Lynn and Molly were also remembered as very nice people with Molly being a motherly type who kept the boys’ clothes and buttons neat before their stage appearances. In addition to their work at WJLS, the Lilly Brothers also worked for a time at WNOX in Knoxville with Lynn and Molly on the Mid-Day Merry Go Round and the Tennessee Barn Dance.

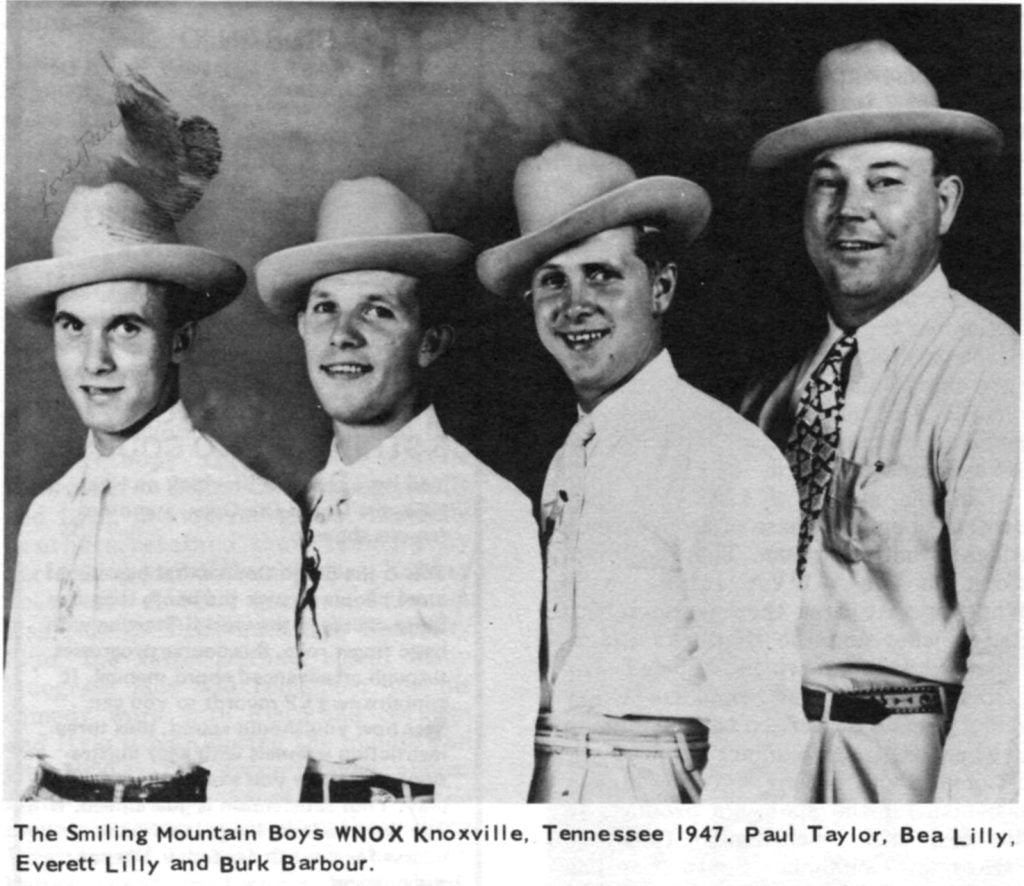

Everett and Bea also worked as a separate act on radio at Beckley. Paul Taylor, an excellent clawhammer banjo player worked with them much of the time and is still a close friend of Everett’s, living near him in Raleigh County. Later, Ed “Rattlesnake” Hogan, a comedian was added on bass. Mel Steele, Little Jimmie Dickens, and the Bailes Brothers also worked at WJLS in the early forties. The Lilly Brothers worked for a brief period on WPAR in Parkersburg. The Lillys and Taylor worked a second time at WNOX in Knoxville with fiddler, Burke Barbour. Lonnie Glosson, the legendary harmonica player from Arkansas worked with them for a time as did George “Speedy” Krise, the well-known Dobroist. Everett, Bea and others often interchanged to form various groups on road shows, one of which was called Burke Barbour and the Smiling Mountain Boys. Another group they worked with for a time was called Speedy Krise and the Blue Ribbon Boys.

While in Knoxville, the brothers were approached by Syd Nathan of King Records, but as he at first proposed using the name of Burke Barbour and his band on the record, the Lillys refused. Later, Nathan told them they could record as the Lilly Brothers, but they were negligent about contacting him again and passed up the opportunity.

It is indeed unfortunate that the Lillys made no recordings during these early years in radio for it was during those years that their sound reached its full maturity. However, there were many other performers of early country and bluegrass music who went unrecorded despite a wide degree of popularity and excellent musicianship. In many respects students of early music get and relay a distorted picture of this period to their readers because they are forced to rely on phonograph records, and much less often, transcriptions for source material. Hundreds of hours of live radio shows good and bad on stations large and small are gone forever. As a result the sound of once important artists such as Budge and Fudge the Mayse Brothers, and Cowboy Loye will probably never be known except to the fortunate few who heard them. For others such as the Bailey Brothers, we have only a small part of their careers on record. And for the Lillys, only the middle and primarily their latter sounds are available on record.

In the spring of 1948, the Lilly Brothers began a phase of their careers which is better known. They began to work on the WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling. At first they worked with Red Belcher and the Kentucky Ridge-runners, a group which included Tex Logan on fiddle and comedian Crazy Elmer (Smilie Sutter) on bass. Although Belcher was a clawhammer banjo player of some talent, his major role was as a salesman for the sponsor’s product. In this respect he was similar to Byron Parker in Columbia, South Carolina whose principle musicians were Snuffy Jenkins and Homer Sherill (and many years before, Charlie and Bill Monroe). Everett and Bea did most of the performing on Belcher’s shows. The group was probably the most popular at WWVA for a time and had three fifteen minute shows daily ranging from early morning to mid-afternoon. With personal appearances almost nightly and the Saturday night Jamboree, opportunities for sleep were limited.

During this period the Lillys received their first opportunity to record. Red Belcher, Bea and Tex Logan cut two sides as the Kentucky Ridgerunners that were issued on the Page label, a small Pennsylvania firm. Everett absented himself from the session, believing that the brothers should record only under their own name. Later in the same year, 1948, the Lillys had a session of their own on Page from which one single was issued. However, no material was ever issued from a session on the Cozy label. Hopefully, this early material, both issued and unissued, will be retrieved and again made available.

Mac Martin, now of Pittsburgh, became a devotee of the Lillys’ music during their years in Wheeling. He recalled recently that the brothers lived with their families in an apartment building on Wheeling Island that housed several Jamboree families including that on “Sunflower” and Marion Martin, the blind accordian player, both of the Doc Williams entourage. In those days the Jamboree originated in the Virginia Theater rather than the present day Capital Theater, but the daily show originated in studios located in the Hawley Building.

It was during this period that Tex Logan’s song “Christmas Time’s A Cornin’ ” was introduced on radio by the group. A couple of years later, Tex gave the song to Bill Monroe who recorded it in October, 1951. The song has since become the standard bluegrass Christmas song.

Red Belcher paid each of the brothers a salary of sixty dollars per week which covered both their radio work and all personal appearances. The Lillys received no other compensation except what little they derived from the sale of their pictures and some travel expenses, as they furnished transportation for their own group and many of the other Jamboree performers in their fifteen passenger stretch bus. Red evidently believed he was overpaying the boys and in 1950 a financial dispute transpired in which Bea and Everett were offered a choice between a ten dollar weekly wage cut or being replaced by Mel and Stan, the Kentucky Twins. The Lillys chose neither alternative and decided to quit. Although offered their own radio show and the opportunity to tour extensively with Hawkshaw Hawkins, they decided instead to leave Wheeling.

From WWVA, they went to WMMN at Fairmont where Everett served as program director supervising the shows of the various live acts that appeared on the station in addition to their own daily show. However, the policy at Fairmont for road shows called for all the performers at WMMN to work together in a package arrangement. According to Everett this meant that there were too many entertainers and as a result the financial pie had to be cut into extremely thin slices. Unable to make much money on personal appearances, the Lilly Brothers soon quit and returned to Clear Creek.

Later in 1950, after a short rest Everett joined Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs playing mandolin and singing tenor. At the time the Foggy Mountain Boys were playing daily radio shows on WVLK at Versailles, Kentucky and Saturday nights at the Kentucky Barn Dance in Lexington. Lester and Earl had attempted to get Everett in their band on previous occasions without success. During this period Bea Lilly returned to West Virginia and worked in Beckley.

While Everett worked with the Foggy Mountain Boys, he participated in their second and third Columbia sessions in Nashville in May and October, 1951, respectively. Among the songs recorded was “Over the Hills to the Poorhouse,” a song co-written by Everett and Lester. Everett had gotten the song from ideas suggested by his mother and old poems such as that by Will Carlton. Flatt and Scruggs later made a second recording of the song for their Hard Traveling album and its continued popularity is illustrated by its being the title song of the third Lester Flatt—Mac Wiseman album. The band also included Chubby Wise on fiddle and Jody Rainwater on bass. After a while Chubby left and Howdy Forester played fiddle on the second session. The Foggy Mountain Boys moved to WDBJ in Roanoke after leaving the central Kentucky area. In early 1952, they switched places with the Bailey Brothers moving to WPTF in Raleigh.

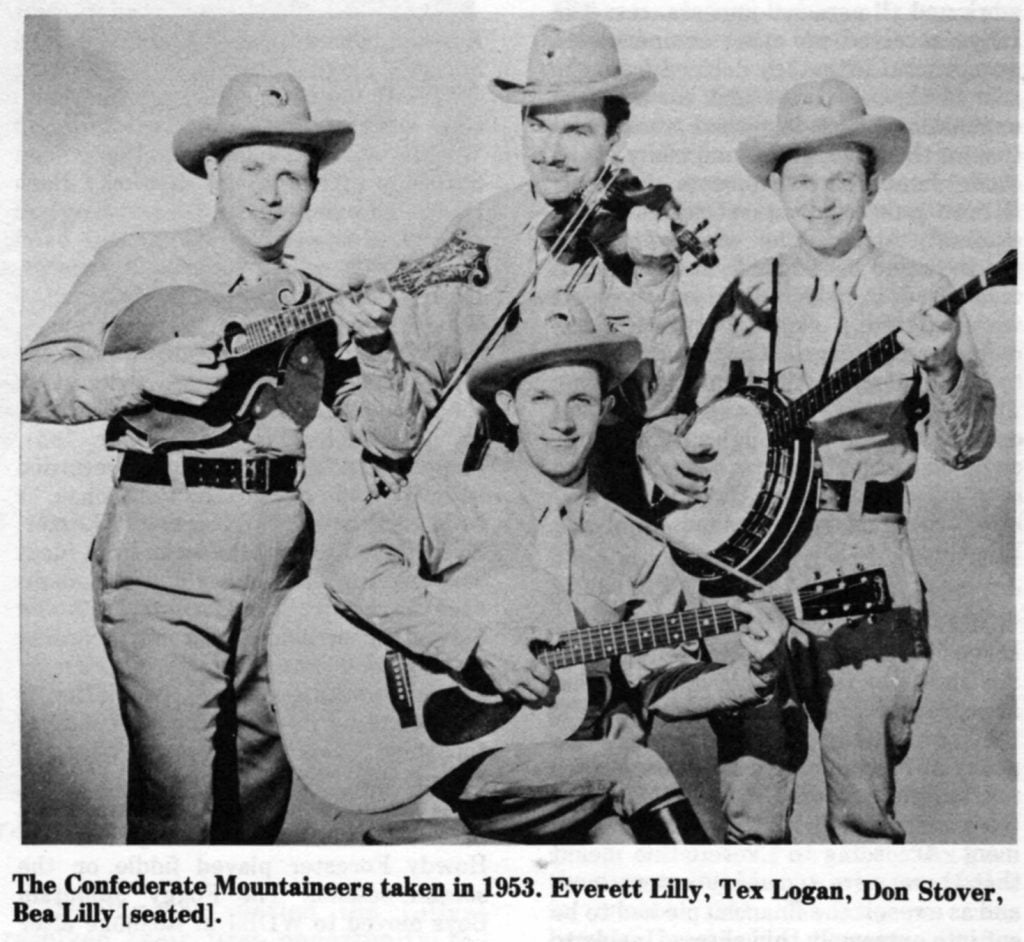

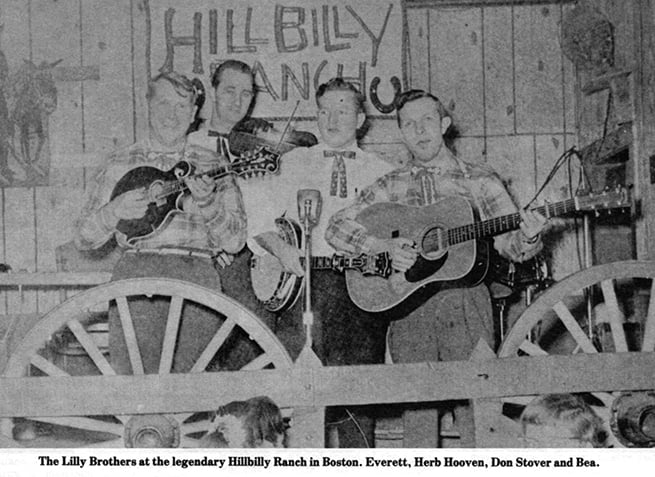

Later that year Tex Logan who had been in Boston with Frank and Pete, the Lane Brothers, stopped off in Raleigh and soon Everett decided to go to Boston with Tex. Bea and Don Stover, a young banjo picker from Raleigh County, joined the group and the four became known as the Confederate Mountaineers. The band worked daily on radio station WCOP and also on the Hayloft Jamboree. The group also played on numerous other country shows in the Boston area helping to sell bluegrass to New England audiences. The group later began to play regularly at clubs, first the Plaza, then the Mohawk and finally a long sojourn at Hillbilly Ranch where their nightly appearances made them a legend in their own lifetime.

Tex Logan left Boston in 1956, breaking up the original group. Herb Hooven from North Carolina played fiddle much of the time, but for brief periods Dave Miller (a Canadian), the late Scotty Stoneman and Chubby Anthony also fiddled with the Lilly Brothers. Don Stover left Boston for brief periods, first to go with Buzz Busby and the Bayou Boys in 1954-55, and second with Bill Monroe in 1956, and last in 1966 with Bill Harrell and the Virginians. During these times Joe Val, primarily a mandolin player, played banjo as did Bob French. Tom Heathwood, a good friend of the Lillys who has also written about their career often played bass or guitar with them too. In later years some of Everett’s children, Everett Alan (who also played with the Charles River Valley Boys), Tennis, LaVerne and the late Jiles Lilly worked with the group occasionally as did Bea’s son, Monty. From time to time, various well known performers in the country, folk, or bluegrass field would come to Hillbilly Ranch to watch and perhaps do a few numbers with the Lilly Brothers. During an eight month period of 1958-1959 Everett returned to Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, working with them on the Grand Ole Opry and their string of daily TV show. However, Everett always preferred working with Bea and their own group and despite his good relationship with Lester and Earl soon returned to Boston.

By the end of the decade, the Lilly Brothers had attracted a solid following in New England which was beginning to include numerous college youths. With the growth of the interest in folk music on campus the Lillys became part of the “urban folk revival” and helped to pioneer bluegrass concerts in colleges, particularly in the New England area but also in more distant locations such as New York’s Carnegie Hall and the University of Chicago Folk Festival. Everett believed that these efforts constitute the Lilly Brothers’ most significant contribution to their chosen musical field.

The Lillys received more opportunity to record during the Boston years. In 1956 and 1957, they recorded eleven numbers for the Event label of Westbrook, Maine. Four sides were released as singles shortly afterward and in 1970 Dave Freeman issued all of the songs on a County album. In 1961, they recorded an album for Folkways and somewhat later two additional albums for Prestige-International, one of which featured the Lilly Brothers only on singing and instrumentation with no fiddle or banjo. Some years later a taped live show made in this period at Hillbilly Ranch was issued on a Japanese album. During Everett’s second sojourn with the Foggy Mountain Boys in 1958, four cuts by Bea and Don Stover were issued on the Folkways album Mountain Music Bluegrass Style.

The tragic death of Jiles Lilly on January 17, 1970 resulted in the end of the Boston phase of the Lilly Brothers career. The incident made a deep emotional impact upon Everett and his family who decided to return to West Virginia (with the exception of the three grown children). A memorable family concert was given at John Hancock Hall on February 14, 1970 and in April the Lillys moved back to Clear Creek. For several months the Lilly Brothers stopped performing and for a time it was doubtful if Everett would ever play again. In the fall, however, they began a thirteen week series of TV shows on WOAY in Oak Hill, West Virginia (Bea Lilly also returned to West Virginia for a time but went back to Boston after a few weeks).

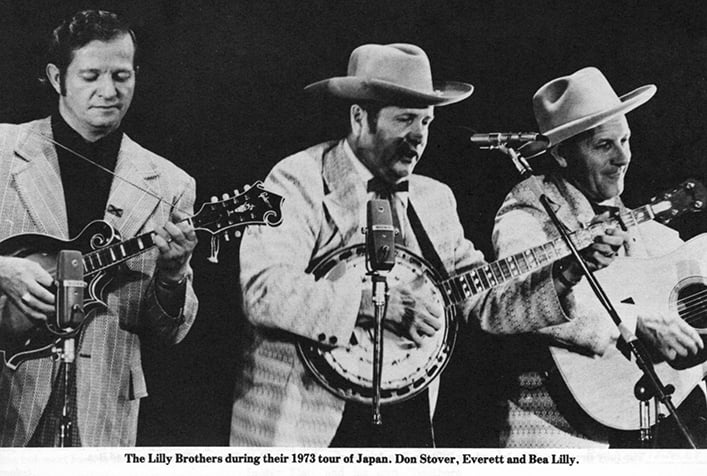

Beginning in 1971, the Lilly Brothers began to appear at a few bluegrass festivals and in the two succeeding summers have broadened the number of their festival appearances. Don Stover and Tex Logan have worked with them on most of the festivals as well as various Lilly children. Everett’s ten year old son, Mark, worked on all their appearances in 1973 and shows considerable promise as an entertainer. The Lilly Brothers also recorded a gospel album on County in March, 1973, their first recording since their three albums on Folkways and Prestige-International during the height of the urban folk revival.

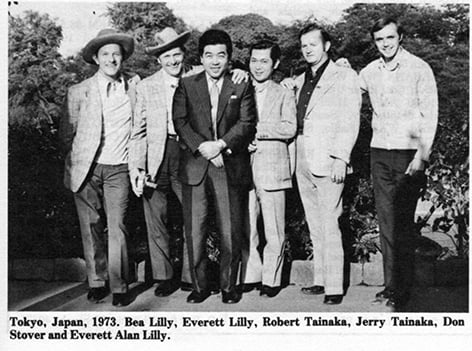

Certainly one of the highlights of the Lilly Brothers entire career came last September when they toured Japan together with Don Stover and Everett Alan Lilly, giving three concerts and recording three albums (one of which has been recently released) during the week they were there. In one concert they played with Robert and Jerry Tainaka (the Smokey Rangers), long-time friends of the Lillys and two of Japan’s more accomplished bluegrass performers.

In their song repertoire the Lillys have always stuck close to traditional old-time and bluegrass material although many of their numbers are among the lesser known old songs rather than the well worn standards. Two such examples are Bert Layne’s “The Forgotten Soldier Boys,” a topical ballad alluding to the bonus march of unemployed World War I veterans in 1932, and Wade Mainer’s “That Star Belongs to Me,” which is a child’s lament to a father killed in World War II. Neither brother has been a notable composer although Everett’s working of “Over the Hills to the Poorhouse” with Lester Flatt and his own “Southern Skies” and “What Are They Doing in Heaven” illustrates that he has some talents along that line. Bea’s composing talents are displayed in his work as the prime writer of “They Tell Me Your Love Is Like a Flower” originally cut by Flatt and Scruggs in 1956, and now a much recorded standard.

At present Everett continues to reside in the Clear Creek community where he works as a public school employee in the winter months and Bea makes his home in Boston. They hope to continue getting together for festival appearances. Their overwhelming reception in Japan has also enhanced the possibility of future engagements in that country. As Vice President of Towa Kikaku and Company, Everett is endeavoring to arrange tours of other American bluegrass bands to Japan. Whatever the future holds, the Lilly Brothers can find comfort in the fact they have done so much in creating and preserving the traditions of old-time and bluegrass music, particularly in those areas basically unfamiliar with that rich tradition.

Share this article

3 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

This article is especially interesting to me. My grandmother was a Lilly. I was also born in Summers Co. WV. I remember the Lilly Brothers band and follow their career to some degree. I did not play Bluegrass until in the 1970’s.but, have been playing Bluegrass Gospel since that time. (Sunnyside Bluegrass. Com.) I would say the Lilly Bro’s contributed and was influential in the popularity of the music in the earlier years. They are distant cousins of mine. Just how far back, I could not tell you. The Lilly family was very influential in the southern Wv area in the earlier years. They have moved all over the world since that time. A lot of them do come back to Flat Top, WV for the reunion each year.

My name is Everett Alan Lilly, oldest son of Everett Lilly. My brother, Tennis, and I were from our father’s first marriage and were raised by our grandparents. Following completion of high school in West Virginia I relocated to Boston at my father’s urging to play music with the Lilly Brothers and work my way through college. Taking the advice of my dad I learned to play the bass as there were few good ones around but a lot of guitar players. I began performing with the Lilly Brothers and recorded with my father and uncle on “Country Songs of the Lilly Brothers.” I began appearing with them on some of their biggest shows including Harvard University and the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. Some of the Newport performances were recorded as well. Of course I worked many nights at the Hillbilly Ranch with them as well. During this time I joined the Charles River Valley Boys, a Boston based group, and recorded “Beatle Country” with them. A highlight was playing bass with Bill Monroe when he appeared in Boston and some of those songs ended up on one of Bill’s live records which I learned about only a few years ago. I was always grateful to my dad for originally suggesting I also learn the bass as he was correct in telling me I would get more work (and thus more money for college). It was at our 1965 Newport Folk Festival appearance that I also played bass for Joan Baez on her show. It was only three years ago that I discovered that Joan’s Newport Folk Festival performance was also on record. Lastly, our first Japan performance in 1973 was recorded on three separate albums and I played almost all of those shows playing a second guitar to Bea. Looking back on it all I was privileged to perform and record with the Lilly Brothers an Don Stover when they were in their prime. A was a musical adventure of a lifetime. A little known fact is that, many years later, I involved my father in teaching mandolin and fiddle to bluegrass music students in a program I developed at Mountain State University in Beckley, WV.

I had the privilege of living on the same street as the Lilly brothers and their families in North Billerica. Monty Lilly became my first boyfriend. I was 13, headed to high school. We had just moved in. A few days into our new friendship, he asked me to his house at the end of our dead end street. When I walked in the front door, to my very big surprise, the Lilly family had set up a band in the living room, and began playing a song to me. My name is Donna. The song was “Oh Donna”. I will never forget it. My mom later told me who they were. WOW is all I can say!