Home > Articles > The Tradition > Preserving Bobby Osborne’s Legend

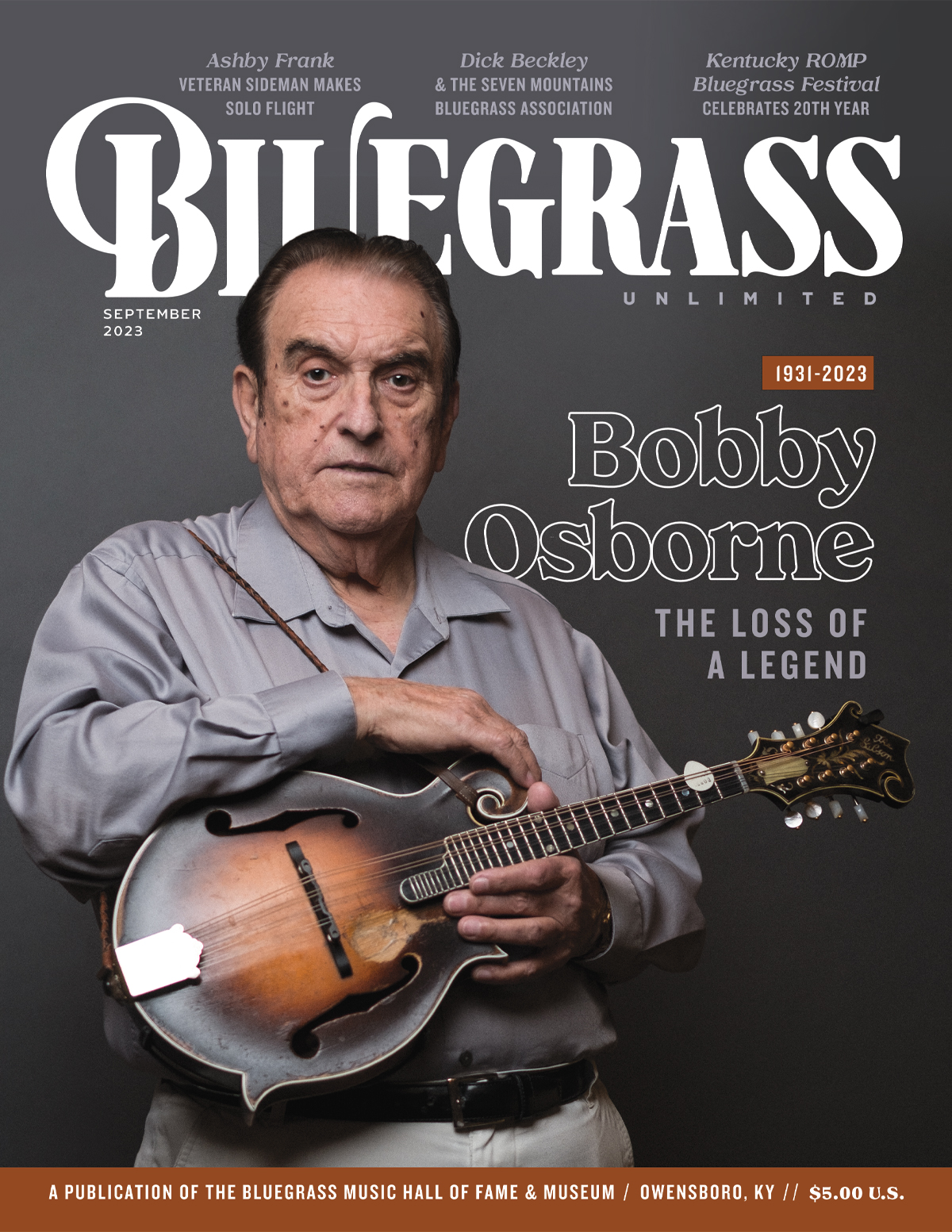

Preserving Bobby Osborne’s Legend

C.J. Lewandowski of the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys says that at fifteen years old, when he met Bobby Osborne, one of his heroes, he would never have dreamed of the friendship that would develop between the two musicians. Over the years that followed, Lewandowski, also a mandolin player, learned from Osborne—music lessons and life lessons. In turn, he was instrumental in keeping the bluegrass legend active up until his death on June 27, 2023, at 91.

Admittedly an “old soul,” Lewandowski has always enjoyed studying the first-generation bluegrass musicians, of whom Osborne represented one of the last. As he was growing up and developing an interest in music, he said, “most of my friends were 50 years older than me, the first-generation Missouri artists.” Noting the impact of the regional aspect of music—keeping the industry from being “homogenized”—he said the band has included a Missouri or Ozark-based song on every album so far. “A good song is a good song,” he said, noting that an album of twelve songs may have only one or two hits, but “it’s nice to showcase those songwriters and those acts. I love digging up these old songs. There are even a lot of Osborne brother songs that have been severely overlooked.”

“I was always attracted to the older generation of people, because their stories and because I felt more comfortable with them than with people my own age,” Lewandowski said. “We didn’t have a lot in common with music and general interests, so I’ve always been leaning towards the older generation of people and music. This year, I had prepared myself that my thirties are going to be hard because that’s the time these people 50 years older than me are going to be in their 80s and 90s, so I’m going to be losing a lot of them. Now it’s really getting hard. I lost Jim Orchard, the guy that taught me how to play mandolin, in February. Jim was like a grandpa to me. He took me under his wing when my grandpa passed away and taught me to play mandolin. Now Bobby is gone too. This year has been tough,” Lewandowski said.

Orchard, his mentor, introduced C.J. to Bobby and Sonny Osborne at a festival in Eminence, Missouri, around 2003. “I met him there at that festival, and it was just a handshake, but I got my picture with him because I was a starstruck teenager. People from the Grand Ole Opry don’t come to Eminence, Missouri,” he added.

He continued to encounter the Osborne Brothers at festivals, particularly when he was playing with The Karl Shifflett & Big Country Show. He even had a chance to take some lessons from Bobby, who taught for the Hazard [Kentucky] Community and Technical College’s School of Bluegrass and Traditional Music. The two become close, so when Lewandowski bought a 1927 F5 mandolin like Osborne’s 1926 “Fern,” he texted Osborne about it.

“He invited me to the house and from then on, I went to the house once a month or more and hung out with him. We just clicked.” Lewandowski pointed out that Bobby was slightly introverted, so it took him a while to warm up to people, “but if he warmed up to you, then you had a friend in him.” Up until the end, he pointed out, Osborne continued to influence younger musicians.

“He was playing the Opry. He was teaching. He literally influenced people until he couldn’t anymore, until the day he passed away, and he is going to continue as well,” he said, mentioning the fourteen-year-old mandolin prodigy Wyatt Ellis who took lessons from Osborne up until the end and is part of the project that was underway at the time of his death.

The music relationship forged between Bobby Osborne and C.J. Lewandowski flourished when COVID set in. During that time, the Grand Ole Opry had only one weekly performance with no live audience. They took into consideration the age of Opry members, trying to protect the more vulnerable.

“They didn’t want him to be out getting sick,” said Lewandowski, “so there was a break when Bobby wasn’t at the Opry for about a year and a half. He wasn’t out playing at all. He was still doing his school lessons, but he wasn’t interacting with people nearly as much. I didn’t go to the house for a while because I didn’t want to be the one to get him sick. I stayed away and not because I wanted to. We were using all the precautions so, in turn, it was really hard on the older generation of people. I saw Bobby get a little down on himself, and it hurt me because, to me, he was invincible. He could do anything he wanted to, and [I hated] for him not to feel confident.” Lewandowski touched base with Osborne’s son Bobby Osborne Jr. (Boj), who confirmed his dad was playing around, but not singing very much and in “kind of a funk.”

“He needed a little bit of legitimacy,” C.J. said, “and I reminded him, ‘The Opry is not calling because of COVID, but it’s coming to an end. Just hold on.’” That convinced him they needed to do something to lift him up. He and Boj brainstormed, and meanwhile, C.J. kept talking to his friends about Bobby. Keith Barnacastle of Turnberry Records in California suggested they make a record with Bobby. Lewandowski told him, “I don’t know; the person that I would have to ask is Bobby.” When he called him to ask if he would be interested in doing a project with Barnacastle, Osborne responded, “Well, I’m not doing anything else. That would be great.”

After COVID, Osborne had been able to return to the Opry once or twice a month and was feeling better and continued appearance there up until his death. When C.J. talked about playing music at the Old Smoke Moonshine Distillery, where the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys got their start in 2014, Bobby said, “Man, I wish I had something like that close to the house.” Lewandowski said he thought to himself, “Here’s a Grand Ole Opry star, country music legend, and he just wants to go out and play some little local places. He loved music so much.”

He conferred with Boj and started calling around. “Bobby was still singing and playing great. He needed something to do.” Just as important, Lewandowski noted, “there’s probably two generations of musicians underneath me now. Why don’t we give that generation an opportunity to see Bobby besides at the Opry?” In early 2023, they set up a three-month residency at Post 82 American Legion Hall in Nashville. “I didn’t know how much of an effect [playing at the American Legion] would have,” he said. “I know that Bobby really loved it, and it kept the band in practice. It really didn’t hit me until the day he died when I saw a bunch of my friends younger than me posting about how much they love Bobby Osborne and the Osborne Brothers. They were posting pictures from the American Legion Hall. That was the only opportunity that some of these kids 35 and younger got to see him.”

Lewandowski admitted that he had experienced some music burnout after COVID. Through that period when there was no work for musicians, he did construction work and even sold some instruments, doing “just what I needed to do to survive.” He began to question whether the amount of work was worth the reward. “Finally, going back to Bobby’s house and sitting with him and talking with him, I realized this guy has been doing this for 70 years at this moment in time, and he loves it more than anybody I have ever seen. His love for doing what he did gave me inspiration and made me love it again. I thank him for that for sure.”

Once the recording project started to develop, they chose to record at Ben Surratt’s studio in Nashville where Sonny Osborne had done some recording. Bobby and Ben knew each other well, so Bobby had spent time there and felt comfortable in the location.

Lewandowski recalled special moments in the studio. All the musicians involved in the project bounced song ideas back and forth, but many of the songs came from Bobby. They chose two or three songs that Osborne brothers or Bobby himself had cut previously. During the second session, Osborne asked, “What if we did ‘Rocky Top’ again?” Lewandowski told him, “I don’t think we can beat that.” When Osborne told him, “Well, I haven’t done it in 55 years. We should do it,” Lewandowski answered, “You’re the guy, so if you wanna do it again, it would be an honor.”

“The rest are songs that he carried with him. One was an old brass band song that he had carried around for a long time that he remembers hearing as a kid on popular radio back in the 40s. He thought it would be a cool bluegrass song. His creativity was amazing, finding material all across the genres. I couldn’t believe the songs he was pulling out, and I’m so thankful for our text messages because he was naming so many songs all the time that I could barely keep up with him.”

C.J. finally told him, “We’re going to do two albums. This is too good not to capture.” He said they planned to get the first one done and released, then to start immediately working on the second.” Bobby told him, “I’m ready to go, and he said, “Let’s get all we can.”

Joining Osborne and Lewandowski on the project were Lincoln Hensley, who did all the banjo work on Sonny’s Granada banjo; Avery Welter on guitar, with Boj Osborne on bass; Aynsley Porchak played fiddle; and Lewandowski laid down the mandolin tracks, sometimes joined by Wyatt Ellis. Josh Rinkel and Laura Orshaw of Po’ Ramblin Boys also played on some tracks, with Rinkel on guitar and Orshaw joining Porchak on twin fiddles. Osborne, Lewandowski, and Ellis even recorded some triple mandolins. They had also captured Bobby’s vocals on nine of the tracks.

Lewandowski admits his disappointment at not completing the album. He said, “We got all we could, but it took me a while to digest: I felt like I let Bobby down that we didn’t get the project done. We didn’t get the two projects together, but I also think he was feeling like he let us down too, and he for sure didn’t.” C.J. added, “Bobby gave me a gift of a lot of things—history lessons for one, the gift of learning straight from him—vocal lessons, life lessons. He gave me his bus! I have a couple of picks he gave me through the years. He gave me his jacket, and I wore it last night [at the Station Inn.] I’ve got little tokens of him, but I have a gift of the last recordings he did, and I think he knew they would probably be his last. He gave us something that no one else could, so I’m looking forward to putting this out and honoring him and exposing people to the voice of 91-year-old Bobby because it is so good.”

Since Osborne’s death, other bluegrass icons have approached Lewandowski, offering to work on completion of the project, with a goal of releasing the album December 7 on what would have been his 92nd birthday. Lewandowski said, “All I wanted to do was make the music that Bobby wanted to make. That’s what we did. We didn’t get to finish it, but we are going to finish it. We’re just gonna do it for him instead of with him.”