Home > Articles > The Archives > Porter Church—“If you can’t use a roll on it, it doesn’t sound right to me.”

Porter Church—“If you can’t use a roll on it, it doesn’t sound right to me.”

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1986, Volume 20, Number 7

He’s rarely played in public over the past two decades, and he’s not on many records, but Porter Church remains among the most eloquent of five-string banjo players.

I may as well say it: in my opinion, when it comes to “golden era” bluegrass banjo playing, Porter is second only to Earl Scruggs. At its best, Porter’s playing enters that mysterious realm where a simple lick is found to contain, on repeated listening, much more than the sum of its parts. It’s the kind of music that stands the test of time.

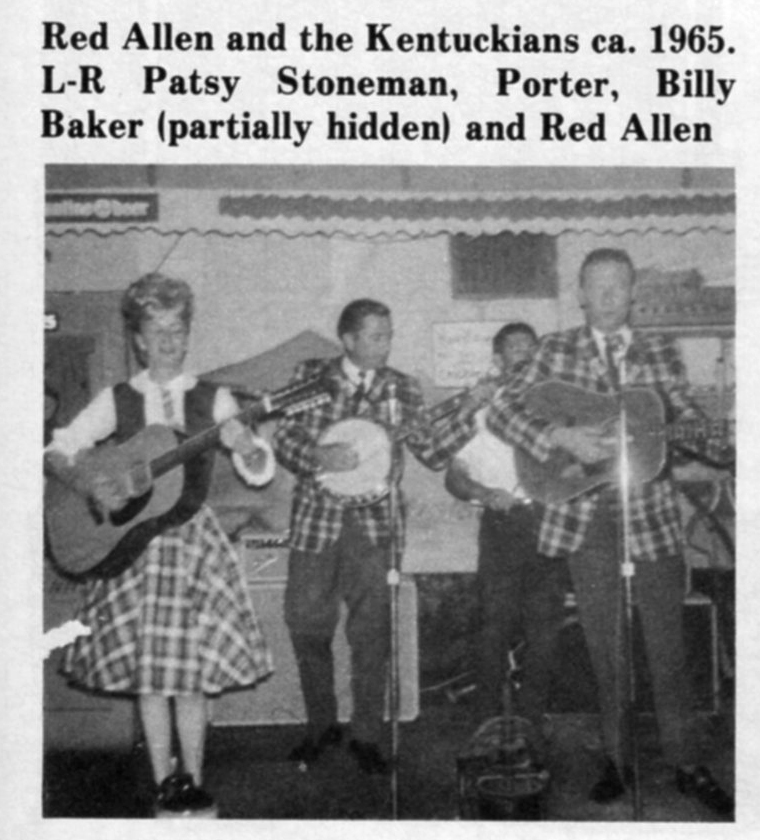

Porter has played in many bands—with the Stonemans, Charlie Monroe, Bill Monroe (as guitarist and lead singer) and at one point had his own group, in which he played guitar, whose members included Bill Emerson, Frank Wakefield and Scott Stoneman. But the only generally available records on which he can be heard are two albums released in the mid-60s, the product of his association with Red Allen. These are “Red Allen and the Kentuckians —Bluegrass Country” (County 704) and “Red Allen and the Kentuckians” (County 710). Three additional cuts with Allen appeared on “Springtime In The Mountain” (County 749) in 1975. Among these, “Keep On Going,” with Porter and Scott Stoneman splitting inspired instrumental breaks between Allen’s powerful vocals, is a classic.

Porter was born in 1934 in Bristol, Tennessee, and raised on a tobacco farm in nearby Virginia. His first instrument was the guitar. “Everybody in my family was a musician. My dad played guitar and banjo, my mother played banjo, piano and organ and my two sisters and two brothers play instruments. My oldest brother, Jim, is a great clawhammer player. When I started, he let me borrow his banjo for a few weeks when he was working in the coal mines in West Virginia. When he came back I was playing a little bit of ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown,’ so he said, ‘You just keep it.’ ”

How did he learn? “I guess from musicians showing me, you know. There were four or five banjo players, other than clawhammer players, around when I started. I heard a lot of that stuff before I ever started playing. Every Saturday night we used to listen to the Grand Ole Opry on a battery radio. We didn’t have electricity then, and batteries were expensive, so you didn’t play the radio except for special events—either the heavyweight championship of the world or the Grand Ole Opry. You might sit there three Saturday nights in a row and not hear Bill Monroe because he’d be on the road. But his show was the only time you could hear a five-string, and of course it was Earl Scruggs.”

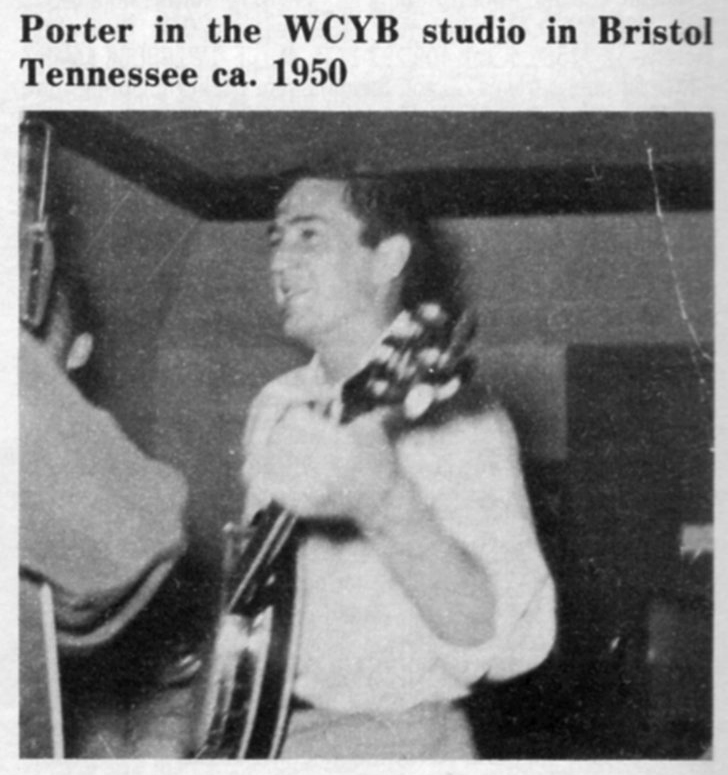

When Porter was growing up, Bristol was indisputably the world’s bluegrass capital and the town’s radio station, WCYB, a mainspring in the careers of the Stanley Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, Jim and Jesse, Charlie Monroe, Mac Wiseman, the Sauceman Brothers and other artists who were then defining a new musical form. It was on WCYB’s Farm and Fun Time, which had begun daily live broadcasts of country artists in 1946, that Porter first saw Flatt and Scruggs. He was in his teens: “Curly King and the Tennessee Hilltoppers was the regular band, playing country music. The Stanleys and the Saucemans and just about all the local bluegrass bands were there. One day I decided I wanted to go down and see what was happening because I’d heard something different, and what I’d heard was Flatt and Scruggs. They had curtains in front of the studio, which was in the General Shelby Hotel, and sometimes they’d open them and let 10 to 15 people inside for the live shows. But the day I went down they had the curtains pulled. They had monitors outside so you could listen but you couldn’t see who was playing. So finally I talked to this guy and he let me go into the studio. That’s the first time I saw Lester and Earl, watched ’em work the mike and everything. Their theme song would just tear you up. Big Jim Lane was the disk jockey there at the time and the emcee for the show. He’d say, ‘It’s five minutes past 12 o’clock and it’s Farm and Fun Time,’ and you’d hear Lester hit his guitar and they’d sing one verse of ‘Foggy Mountain Top’ real slow, and pause, and then Earl would start off on ‘Train 45’ and I mean burn it up! They stayed at WCYB a year and a half. Those days are gone forever.”

Porter also admired the banjo work of Joe Medford, respected for his clean and tasteful backup on early Mac Wiseman recordings, and Rudy Lyle, who played banjo with Bill Monroe. Lyle was particularly influential. “The first record I ever had was a 78 of ‘Rawhide’ one of my sisters bought for me. Rudy Lyle’s picking on that is just out of this world. When he starts his break and then goes into the F, he does a roll that I’ve never heard duplicated. I can play it pretty close, but I’ve never heard anybody do it like Lyle. Nobody can do it exactly.” —not even Rudy.

Porter’s first job was with fiddler Ralph Mayo, who between engagements with the Stanley Brothers fronted his own band, the Southern Mountain Boys. “One day Ralph approached me and asked if I wanted to pick banjo with him. I told him I’d try it. So he put me on Farm and Fun Time. He started off on ‘Cacklin’ Hen’ so fast I just stood there and watched him play it—the theme song! But eventually I caught on. I worked with Ralph almost two years. Then I formed my own band, the Log Cabin Boys. In those days you’d go out and maybe drive 150 miles each way and sometimes you’d make a dollar and a half. If you made five dollars you had a great night. In the schools and other places you played, kids paid a dime, adults a quarter, and you might have 50 to 75 people. To draw more than that, say 200 people, you had to be something special. Many a time you’d get home at three or four in the morning, but you’d be ready to go again the next night.”

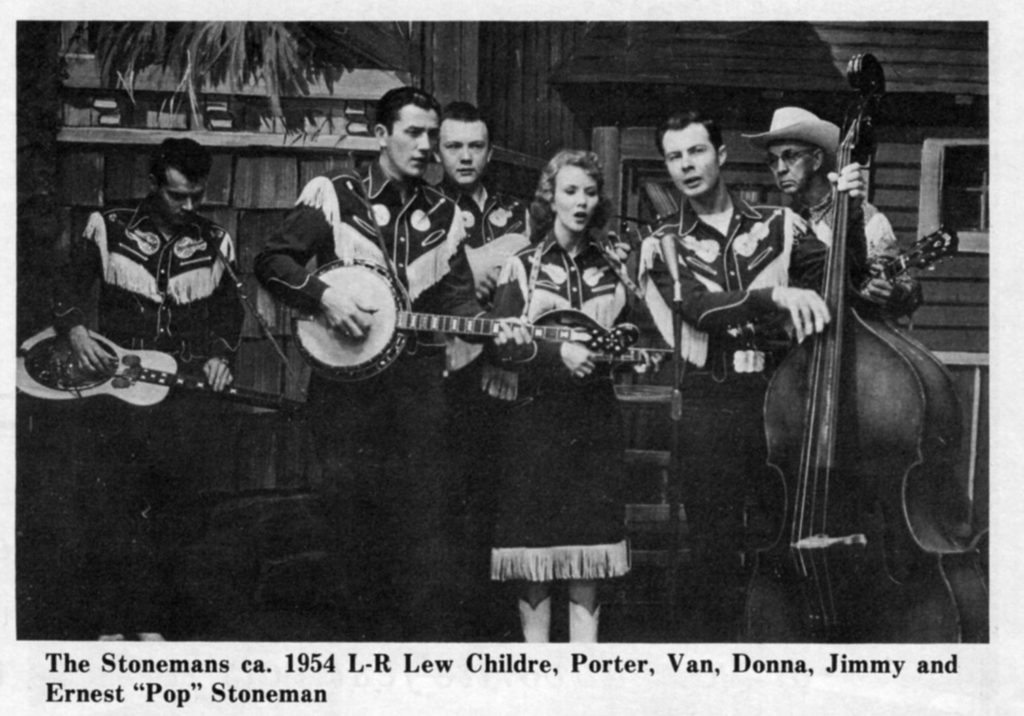

In 1953 Porter moved to the Washington, D.C. area in search of more lucrative musical employment. “I saw the Stonemans’ picture in the window of the Famous restaurant and waited out front all day long for them to come in at 9 p.m. I waited for them to do one show and then went in. I had a banjo with me and Scott Stoneman asked me to come back to the kitchen and I played ‘Dear Old Dixie’ for a minute or so. Scott told the management he wanted me on the payroll. A union rule limited groups to four musicians then, so Scotty asked me if I would play for the kitty. We had a bucket up on the stage. He said if I didn’t make as much as they did they’d make up the difference. The first night I played they made $12.50 apiece and I made 40-some dollars, which was more than I’d been making in a week back in Tennessee. So I played there for just the kitty for a few years and made more than they ever made, but they never did say anything. It didn’t matter to them.

“A black guy named Calvin ‘Hound Dog’ Rutledge used to play Fats Domino and Little Richard stuff on the piano at the Famous during intermissions. He’d get started on ‘Blueberry Hill’ and Scott would jump onto the stage with Calvin and play guitar fingerstyle. He played some crazy stuff on a guitar when he was in the mood. He’d get way down on the neck and make some of the wildest chords you ever saw, but it fit right in. Calvin, he loved it. The Famous was the place in Washington in the 50s. People like Roy Clark, Jimmy Dean, Marvin Rainwater and Bobby Stevens were always showing up.

“I guess the high point in my life was playing the “Arthur Godfrey Talent Scout” show with the Stonemans in 1955. Bluegrass on CBS network television was just unheard of—and we won! We did one song and got $680 each plus about $300 a day for expenses. When you won you were automatically on the daytime show for a week, and they kept us on for two weeks, with Pat Boone and the McGuire Sisters. I couldn’t believe we’d won it. There was some tough competition, a violinist and a beautiful girl, a pop singer, who was really good. $680 for one song was gold. We stayed at the Waldorf-Astoria.

The group returned to the Famous, where Porter finally was put on the payroll, and also played the Jimmy Dean show televised weekly from Washington’s old Uline Arena. The Stonemans were offered a job at the Ozark Jubilee; some family members didn’t want to go, and Porter quit the band to return to Tennessee and Farm and Fun Time to play with a group headed by Red Malone. One day Smokey Davis, a bassist-comedian who had worked with the Stanleys and Flatt and Scruggs, told Porter of a job possibility with Charlie Monroe. The next day Monroe came to Bristol from Winston-Salem, North Carolina and offered Porter $105 a week. “That was $25 more than anybody else in the band was making and, buddy, I’ll tell you that was some good money in those days. Most of the expenses were paid, too. I never worked with a better man than Charlie Monroe.” The band included Walter Dragoo, electric guitar; Frank Blevins, mandolin and fiddle; H.P. Hickman, bass; a girl named Barbara and a comedian named Luke —a seven-piece outfit. In addition to concerts, they played three television shows and a live radio broadcast weekly. Porter was forced to leave when he was drafted and sent to France in 1956. “Charlie and his wife Betty used to write to me the whole time I was over there and they offered me a place to stay when I got back.” When Porter returned from 16 months in the Army, however, the group had disbanded. “They really wanted to make it, but, boy, at that time it was tough. Elvis Presley was top dog, and if you didn’t play rock-and-roll you had a hard time. Other country singers — Ernest Tubb, Marty Robbins, you name it — were all singing rock-and-roll to keep up.”

Porter returned to Washington to rejoin the Stonemans for about a year. One night he got a call from Buffalo, New York. It was Bill Monroe, in need of a banjo player. Porter caught a plane and joined the Blue Grass Boys, who at the time included Jack Cooke on guitar and Dale Potter on fiddle, for a Canadian tour. Porter recalls an unusual experience one night backstage: “Monroe, Johnny Cash, Merle Travis and everybody were singing ‘I Saw The Light’ between shows. The door opened and in came about four black guys. They listened a while, and finally one guy came over and said to Monroe, ‘These guys want to meet you,’ so Bill got up and shook hands with them. They said they really loved bluegrass; Bill asked them if they played, and they said they did. Now this is the truth, they took out their instruments and stood there and sang and played really well. That’s the only time I ever heard a black bluegrass group. One guy played mandolin really good — strictly Bill Monroe stuff.”

When the band returned to the States, Jack Cooke quit, to stay in Baltimore, and Monroe asked Porter if he’d like to come to Nashville. Porter accepted the offer to take Cooke’s place as guitarist and lead singer. It was 1960, and the ever-shifting Blue Grass Boys personnel during Porter’s tenure of somewhat less than a year included Rudy Lyle, banjo; Bobby Hicks and Joe Stuart, fiddles; and Bessie Lee Mauldin, bass. Porter lived on Monroe’s farm in Goodlettsville, about 15 miles from Nashville. “He had about 250 acres of timber and farmland, 75 foxhounds and a couple of old mules. When we were off we’d take the mules and go up in the woods and cut some logs and haul them out. Both of us worked hard and enjoyed it. He had tenants who took care of the place when he was away. I never had a hard word with Bill. We’d go places together, you know, and sit around a tree, talk and pick, just him and me. There was an old shed out behind his house piled floor to ceiling with letters he’d gotten over the years addressed to the Grand Ole Opry—boxes and boxes. I sorted through it one day and found old song books, pictures, all kinds of stuff. Behind one sackful was an old mandolin case. I dug it out and it was an old round- hole Gibson, the one he recorded ‘Get Up John’ with. When he went on a trip to North Carolina, I stayed behind and cleaned up the mandolin and put new strings on it. Later, when we got in the car to go to a job, I brought the mandolin with me and took it out. I already had it in the ‘Get Up John’ tuning and started to play it. Bill kept looking at the mandolin. Finally he said, ‘I had a mandolin like that… that is my mandolin, isn’t it!’ He kept that thing right with him after that. This was the mandolin he’d used in place of his F-5 after he sent it to Gibson to be fixed.”

After leaving Monroe—he was growing tired of the road —Porter returned once more to the Washington area and settled in Manassas, Virginia with his wife, Betty, whom he married in 1962, and began working as a painting contractor. For several years he did little performing. But the urge gradually intensified, and Porter began playing clubs in the Baltimore-Washington area. It was around this time that he organized his own group with Bill Emerson, Frank Wakefield, Scott Stoneman, Jack Stoneman on bass and Lew Childre on Dobro. They found work at a placed called Whitey’s in Washington. “Boy, it was a good band. We’d play for about an hour and the patrons would fight for 30 minutes. I think it got everybody a little nervous. That band didn’t last too long. Later, though, we went to Baltimore and tried it again and then broke up a second time.” Then Whitey, who had remodeled his club, contacted Porter, who recruited Jack Cooke, Wakefield and Billy Baker on fiddle. “The first night, they had one of the bloodiest battles you’d ever want to see. We played there a few weeks and then Jack left —it was a little too much for him.”

This hectic period ended when Porter teamed up with the Yates Brothers and Red Allen, filling in for Bill Emerson, who had left to play with Jimmy Martin. The group enjoyed a lengthy engagement at the Shamrock in Washington, for years the city’s closest approximation of a bluegrass “listening club.” It was this lineup —Red Allen, guitar; Porter, banjo; Wayne Yates, mandolin, and Bill Yates, bass—that recorded the “Bluegrass Country” album in 1965 with the addition of Richard Greene, then emerging as an uncommonly gifted fiddler whose primary influence was Scott Stoneman. The group landed a regular spot on the WWVA World’s Original Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia. With the conclusion of the stint at the Shamrock, Wayne Yates left and was succeeded on mandolin by David Grisman. Red and Porter formed a partnership and, in 1966, recorded “Red Allen and the Kentuckians” with Craig Wingfield on Dobro and Jerry McCoury on bass. Porter recalls the making of this outstanding album: “It took a total of three hours to make. I don’t think there was a double cut on anything. When we got to the studio, they said to “just go ahead and start playing.” They were adjusting the knobs and everything, getting everybody balanced out.

We were just standing around and nobody had any idea that the instrumental we were playing would be released as ‘Bluegrass Blues.’ Then Red started singing ‘Milk Cow Blues’ or something, and they kept all that stuff. David Freeman, the producer, said that’s what he wanted—to catch us all off guard. On the trios—we were standing around one microphone—I sang lead, Red tenor and Grisman baritone. Dave Freeman gave us I think 100 albums apiece. It seemed like everybody else was going out and paying for studio time and all that. But Red and I got $500 apiece right off the top. The checks were laying there when we walked into the studio. And the distribution was good.

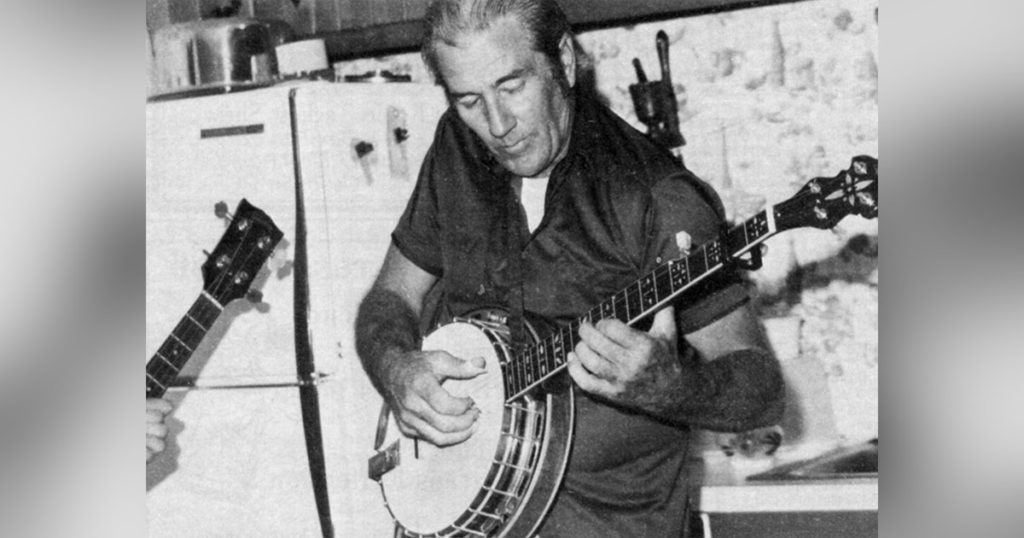

Porter and Red continued their partnership for a time until Red moved to Dayton, Ohio. Since then, Porter has seldom played in public but his banjo work, now mostly confined to informal jam sessions, is as sharp and intense as ever. His son Kevin, 22, who played banjo with Hobbs and Partners, has clearly inherited his father’s talent. “I tried to get him started on the fiddle,” Porter says, “but he didn’t last long— he jumped on the banjo. You know, it’s really something, because it seems like that’s one instrument that runs all the way back through my family. My grandfather, my uncles—it seems there was a banjo player as far back as I can think. It seems like Kevin was picking in no more than a month. I never sat down and worked with him on the banjo; he just started playing in the evenings by himself when he’d come home from school. I mean I didn’t even realize he was picking. But one day I came in and sat down and listened to him a minute and I knew he had the idea.” Kevin’s playing, like Porter’s, is firmly Scruggs-oriented.

Of contemporary bluegrass, Porter says, “You hear it one time and you like it. But it doesn’t last. Flatt and Scruggs, you know their music sounded so fast, like it was impossible to keep up—things like ‘Durham’s Bull’ and ‘Black-Eyed Susie.’ They play music today a lot faster than the original recordings. But it doesn’t sound as fast. ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ is not really fast, but Scruggs drove the banjo so hard and the notes so quick that if you try playing along with it, the backup and everything, your right hand will be tired at the end.

“If you can’t use a roll on it, it doesn’t sound right to me. You’ve got to be with three or four musicians with the experience to play without practicing or working on it. If you’ve more or less learned mechanically, in just a matter of days you can work right in with them because you’ll relax and they’ll make it easier for you. If you fall in with a good band they won’t let you do wrong. But if you’re advanced enough to know right from wrong, and you’ve got some other guys that are still fighting at it, it’s a strain and you can’t really play what you know. A lot of bands today, if you’ve heard one song, you’ve heard everything they do. Of course, the public are the easiest people in the world to fool when it comes to that. As long as it’s loud and fast they could care less. But if a group like that had to play for, say, 25 people in a place where you could hear a pin drop, they’d better do something that’s right or they’re going to get up and walk out. Playing in clubs can be good for practicing licks over and over. But you can get rough, too. If you play clubs for 10 years without recording, when the day comes to record you’ll find yourself digging and scratching. That’s one thing Flatt and Scruggs didn’t have to do. Back in those days they didn’t play clubs, they played school houses and auditoriums. And another thing—they started with a band and they kept that band. Curley Seckler joined Flatt and Scruggs in 1949 and was still with Flatt in 1977, although he did take a number of years off. Paul Warren stayed with him; Jake and Josh worked with him for years. Of course they were really good players, but their sticking together was what made that band click.

“Thinking back, I probably enjoyed being on Farm and Fun Time as much as any place I’ve played. They usually had four bands from noon to 2 p.m. You got 15-minute shows. You’d just sit back when you weren’t playing and hear some good music, too. That was where it all originated as far as I’m concerned.

“The first time I saw Earl Scruggs I knew that some way or another I was going to have to learn to play a banjo like that. And I’m not sorry I did. I had a great time playing. I miss it, and like to be around it sometimes, and sometimes I’m sorry when I am because it makes me want to get back in it. I don’t plan to. But I sure like to hear it when it’s good. I like to sit down and play those old tapes of Lester and Earl on the Martha White show in the early 50s. I can listen to that for hours and hours and never get tired of it.”