Home > Articles > The Archives > Pete Wernick — “Dr. Banjo”

Pete Wernick — “Dr. Banjo”

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 1987, Volume 21, Number 10

It’s 1963 in Washington Square Park, downtown Manhattan, on a Sunday afternoon. A young man of seventeen carrying a banjo case is inching his way forward through a crowded circle of bystanders toward its center where several bluegrass musicians are jamming near a fountain. The seventeen-year-old finally emerges in the front row where he watches and listens, fascinated, dreaming of the day he’ll be invited into this inner sanctum to play banjo and sing. As it is, though, he’s not ready yet. He’s only had his banjo for three years, he still has a tendency to lose the rhythm, and sometimes, when he gathers up the courage to take his banjo out of the case at these jams, one of the better players borrows it for the rest of the afternoon, preventing “the kid” from playing it.

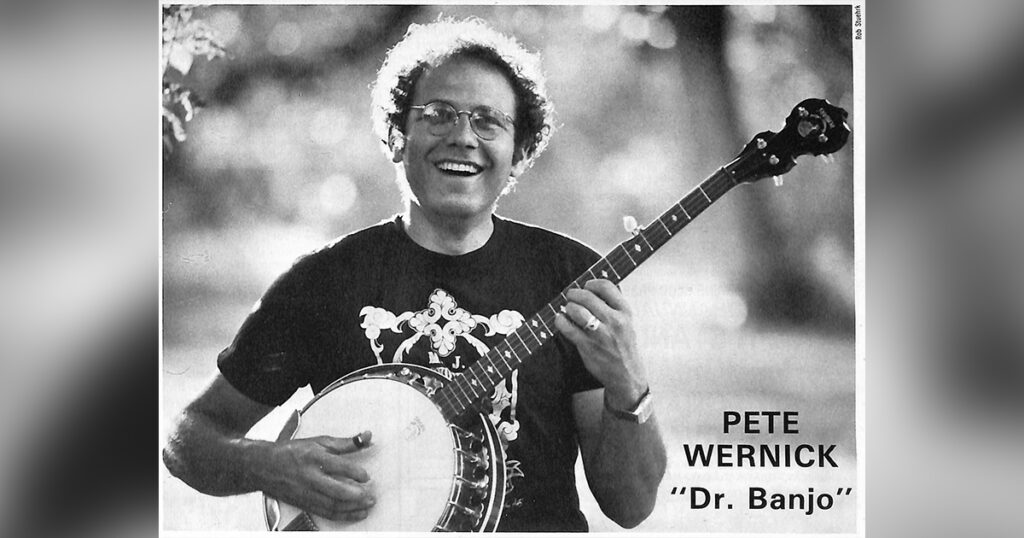

The ensuing twenty-four years find Pete Wernick well-established within the inner sanctum of professional bluegrass. In addition to being Hot Rize’s renowned banjoist with a popular solo album to his credit (“Dr. Banjo Steps Out,” Flying Fish 046), he is one of the most respected banjo instructors in the five-string world. Pete’s Bluegrass Banjo instruction book has sold nearly 200,000 copies; he has produced a popular bluegrass songbook and a Music-Minus-One series of albums in the bluegrass genre; he has done a Homespun Tapes banjo method in video format; he captains numerous banjo workshops throughout the United States; he has co-authored with Tony Trischka a massive volume of interviews, tabs and photographs of the world’s best-known banjo players to be released later this year; and he’s currently sitting on two more banjo instruction books as well as original material for two more solo albums.

So how did this teenager who could barely muster a three-finger roll in 1962 accomplish all this? “Well, there was virtually no tab back then. It was a lot of trial and error to get three fingers working and playing in time, but it was all based on the inspiration of Earl Scruggs, and it still is, really. He’s still by far my favorite banjo player, and even though I’ve tried to develop a lot of my own style, I’m always going back to try to get the sound and the impact that he got with his playing.”

Pete began playing his father’s banjo at age fourteen. His first musical endeavors were of the folk ilk so widespread during the sixties. “Pete Seeger was kind of popular around that time, and some of my friends were playing that kind of music so I learned a little lick here or there from a friend. The first official kind of group that I was in was a folk style trio like the Kingston Trio, and I would occasionally use Scruggs style sounds and it would work out pretty well.”

Soon, Earl Scruggs’ banjo style became Pete’s ultimate goal so he veered away from the folk sound in favor of the traditional bluegrass style. “Before I had ever tried to play banjo I happened to hear a record of Earl Scruggs, and it wasn’t just any record —it was the ‘Foggy Mountain Jamboree’ album which still is the one that I’d take to the desert island, the famous desert island that has a stereo on it and you need records there,” Pete laughs. “And the first cut that I heard was ‘Shuckin’ the Corn’ which is just an absolute fabulous rendition of what a five-string banjo can sound like. A couple of years later, when I’d learned some folk-style banjo, I decided I’d try to figure out what Scruggs was doing. It came slowly, but my commitment started from there.”

When Pete left his high school music buddies behind and became a freshman at Columbia University in New York City in 1962, he began combing the environs searching for other people with whom he could play music. “There weren’t many people around my college who were interested in playing bluegrass music, and that’s putting it mildly. In the whole city of New York there might have been about twenty people who were interested in playing bluegrass music, but I found them.”

Pete’s study of bluegrass then began in earnest. He hosted one of the few all- bluegrass radio programs existing at that time, on WKCR, the Columbia University station, where he was treated to live music by Red Allen and the Kentuckians and Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys. In fact, Pete purchased the banjo he’s been playing for the past twenty years, a 1931 Gibson RB-1, from Porter Church, Red Allen’s banjoist, after meeting him at the radio station in March of 1966. Additionally, Pete was befriended by Jody Stecher and David Grisman who offered equal doses of praise and constructive criticism about his radio program, and with whom Pete sometimes jammed. “All of that was some of the best experience I could have had as a college kid in New York trying to get involved in bluegrass. It wasn’t at the stage in my life where it might have been possible for me to go off and tour with some of the famous mentors of bluegrass, but I was learning a lot from listening to records and playing with people around New York City.”

When discussing his years at Columbia, Pete’s memories seem to center almost entirely around music rather than academia. Although he excelled as a student of sociology, his first love was bluegrass. It is difficult to imagine Pete Wernick finding time to sleep during these years. On top of his regular college studies, radio program, banjo practice and jamming, he was also a member of the Orange Mountain Boys, the first serious bluegrass band Pete had hooked up with thus far. The Orange Mountain Boys consisted of Bob Applebaum on mandolin, Hank Miller on guitar, Ed Goff or Chet Stone on bass, and were based in New Jersey. “It was worth about a two-hour commute each way in and out of New Jersey taking a total of three different trains,” says Pete, “and I would spend the whole weekend hanging out there and practicing. We got a fair amount of gigs around New York and New Jersey and played what I recall was pretty good music.”

In 1966 Pete began his graduate work in sociology at Columbia. Although the Orange Mountain Boys had since disbanded, Pete maintained his involvement with bluegrass music in and around New York. Two of his closest associates during the late Sixties were guitarists David Nichtern and David Bromberg, both of whom Pete credits with broadening his circle of musical influences, “which was a very healthy thing, I think, for my musicianship.” But there were many other influences. Progressive rock and roll was an up and coming musical force, and New York’s Fillmore East, where Pete attended many concerts, hosted some of the best rock talent in the nation. Memorable impressions were felt by the Grateful Dead, B.B. King, Sam and Dave, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and, in particular, the Beach Boys. “The Beach Boys’ music really appealed to me with its complexity and the beauty of the harmony singing and the beauty of the melodies. It left a big impression on me, and I’ve always tried to keep that side of my musicianship someplace in there, that feeling of melody and beauty in my playing, whether I’m playing bluegrass or any other kind of music.”

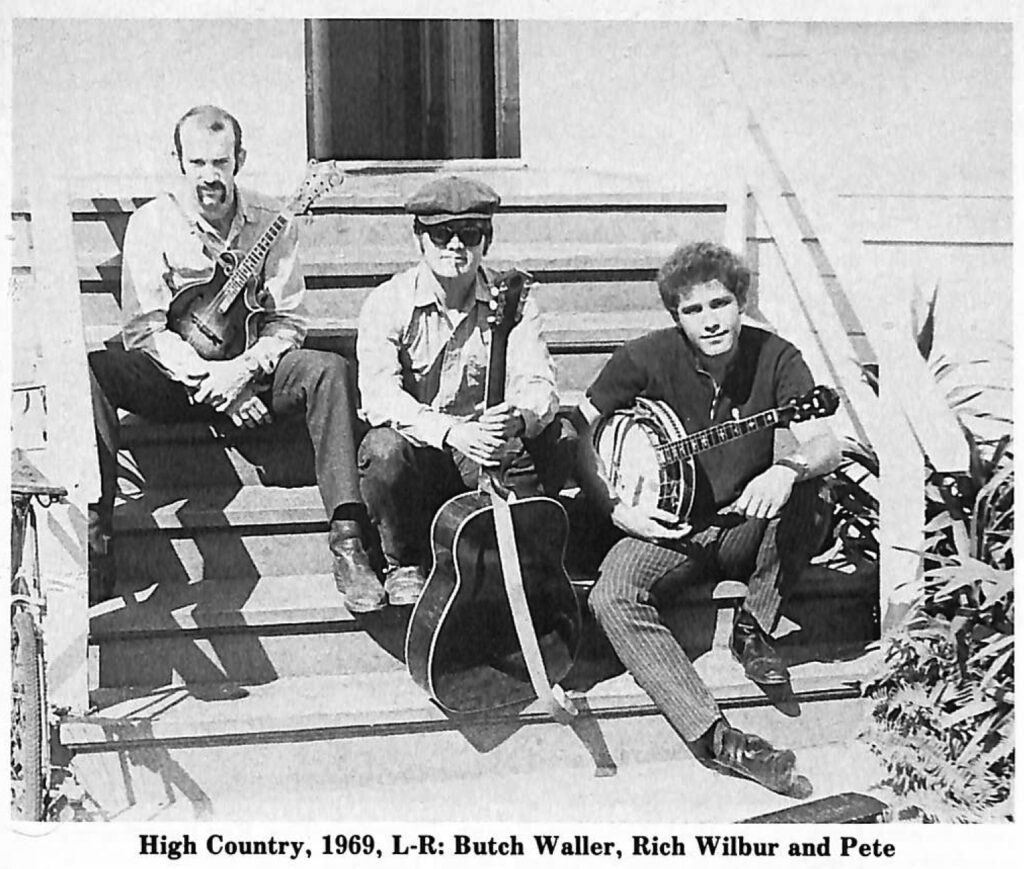

The summer of 1969 found Pete at a point in his graduate work where he was able to take the summer months off, so he packed up his tiny car and headed west. It was during this summer while staying briefly in Colorado that he met his wife, Nondi Leonard, who later became one of the lead vocalists in the Country Cooking band. Pete continued westward to Berkeley, California, a veritable spawning ground of California bluegrass, and joined High Country. “That was my biggest bluegrass experience up to that date because these guys weren’t just playing because they really liked it; they were actually making a fair part of their living through playing this music, they already had a respectable following, and they were more professional at it than anybody I had ever played with before.”

Later that summer in California, Pete had the opportunity to perform with Vern Williams and Ray Park. If his recent experience with High Country had seemed to be the apex of his career up to that time, playing with Vern and Ray added further to Pete’s growing sense of musical confidence which would eventually lead him away from the scholarly life and into a full-time musical career. “That was the closest I ever got to the kind of exposure that city guys or anybody getting into bluegrass needs. Vern and Ray were both country guys who really knew all about bluegrass and felt it in their bones. When I’d be up there playing with them on stage, I felt like I just had to produce and play the kind of music that would fit in with what they were doing. I couldn’t just go on little flights of fancy because everything going on onstage really had to mean something or it just wouldn’t sound right. So I was flattered that they considered me worthy of playing with them and also tried as hard as I could to meet their expectations and to make them sound as good as I could.”

Pete and Nondi returned to New York in 1969, moving upstate to Ithaca, home of Cornell University, where Pete worked as a research associate in exchange for office space and access to research materials needed for writing his Ph.D. thesis. At first, Pete’s quest for fellow bluegrass musicians in Ithaca proved unfruitful. In the meantime, he and Nondi sang country duets together, with Pete playing guitar and composing some of their material. Joining them occasionally on guitar was Russ Barenberg, then an undergraduate at Cornell.

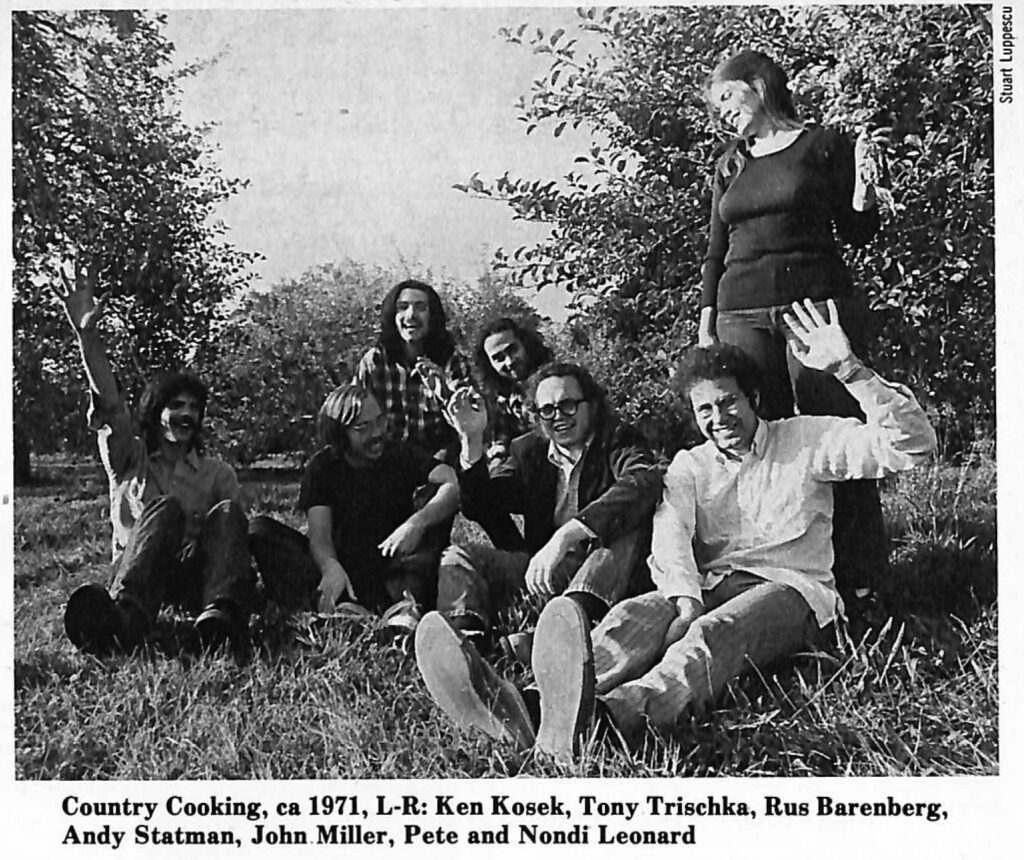

It was in 1970 at a David Bromberg concert in Syracuse that Pete met Tony Trischka, who was to become one of Pete’s closest friends. This alliance soon evolved into the Country Cooking band, one of the first groups to record on the Rounder label. Country Cooking’s first album (Rounder 0006), which was recorded in May of 1971 in a room of the student union at Cornell University using only two microphones and a borrowed tape recorder, has sold more copies (30,000 to date) than any album on which Pete appears. This first recording venture was intended to be an album featuring banjo duets by Pete and Tony Trischka, but the enthusiasm fostered among all the musicians as a result of its production led to the development from informal to working band. “I realized that it was possible to book the band into college gigs all around New York state, and this, along with the success of the record, helped make more of a serious endeavor out of the whole thing. We got more and more college gigs, and we made another record, so even while we were all continuing our academic scenes, this was happening on the side and it was sort of whetting everybody’s appetite for future musical activities.”

As the driving force behind Country Cooking, Pete quickly learned the ropes of band management and booking. From 1971 through 1975, Country Cooking made frequent appearances throughout the New England states, and their four albums were well-received by reviewers from all facets of the music industry. These successes led Pete to contact several major record labels, but although a few expressed serious interest, no contract was forthcoming. [For further reading on Pete’s Country Cooking days, see “Confessions of a Bluegrass Musician From New York” by Pete Wernick, Bluegrass Unlimited, May 1977.]

Soon after Pete finished his doctoral thesis in 1973, John Miller of Country Cooking suggested that Pete write a banjo instruction book. “I was enthused about the idea because I realized that a book was needed and it just might sell very well.” Because Pete had already been teaching banjo on a one-to-one basis for nearly ten years, writing the book was a relatively easy task. “I just sat down at the typewriter as though I was teaching one extremely long lesson to one person who needed to have everything spelled out carefully, and since I’d already been doing it, it kind of fell right out from memory.” Initially, Oak Publications was not interested in publishing such a manual, but “somehow or other they managed to change their mind” and the book was released in 1974. In 1976, Oak also published Pete’s Bluegrass Songbook, another successful venture. “The books changed my economic situation dramatically and I realized I didn’t need my job at Cornell to survive on. I had already gone from working half-time to working quarter-time because of my musical commitments, and when I was asked by my boss how much I wanted to work the following year, I said, ‘I think I’ll just be quitting this year.’ I found that music was a more fulfilling thing in my life.” Pete’s Ph.D. in sociology wasn’t entirely for naught, however. Somewhere along the way he was dubbed “Dr. Banjo,” and the name stuck. “I still wear my old-era, egghead-looking spectacles. It fits my image.” And, during the late sixties, Pete coordinated the student effort in the New York City area for the McCarthy presidential campaign. “It was interesting blending that along with my graduate school career and my music and being in all three of those worlds at the same time.” Later, while in Ithaca, Pete stayed politically active and produced an alternative radio news program. Today, he employs his sociological background to share with his students the “sociology” of jam sessions, band management and self-motivation. Perhaps Pete’s limitless patience and understanding with regard to teaching are also attributable at least in part to his sociology background.

The lure of the Colorado Rockies drew Pete and Nondi from New York to the rural area outside Boulder, Colorado in 1976. With their departure, Country Cooking disbanded. Pete proudly points out that each of its members on the first album has since gone on to record a solo album and make a career in music. “It was one of those situations where a professional music business situation came up and turned what were mostly just enthusiastic amateur musicians into people who were able to get serious about their talents.”

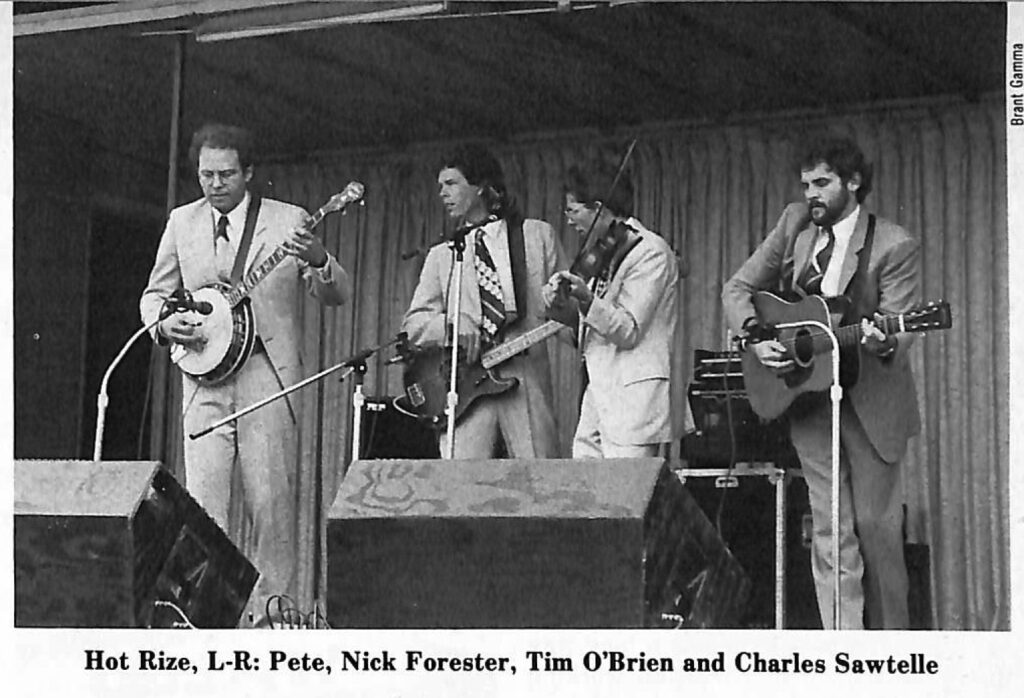

Pete’s banjo playing had now solidified into an identifiable style and it was time to showcase both his sound and his original compositions. “Dr. Banjo Steps Out” was recorded in 1977 primarily in Boulder, although a few cuts from the obscure Extended Play Boys (aka Country Cooking) sessions of 1975 in New York were also included. Two of the back-up musicians on this solo album were mandolinist/fiddler/singer Tim O’Brien and guitarist Charles Sawtelle whom Pete had met at the Denver Folklore Center. The three of them had been performing informally under a variety of group names (Rambling Drifters, Drifting Ramblers, etc.). As with Country Cooking, the recording situation helped crystallize an informal alliance, and a new band was born. With the addition of Nick Forester on electric bass in May of 1978, Hot Rize took the form it still holds today.

In very short order, Pete’s knowledge of the music business, coupled with the inherent talents of Hot Rize’s members, found Hot Rize in great demand, and the band has since toured throughout the United States, Europe and Japan. As their three albums on Flying Fish and their latest on Sugar Hill illustrate, Hot Rize’s sound is steeped in traditional bluegrass but flavored with contemporary arrangements and unique instrumental styles. Hot Rize’s wacky alter egos, Red Knuckles and the Trailblazers, have two albums to their credit in their classic 1940s country and western style. The show-stopping live performances by the “two bands” are among the most memorable and entertaining in the bluegrass field today, and the foursome’s future looks exceedingly bright.

Even though Hot Rize is unquestionably a bluegrass band, they are occasionally shunned by festival promoters who find an electric bass unacceptable, and by still others who invite Hot Rize to play while excluding Red Knuckles and the Trailblazers. Another wedge between Hot Rize and the traditional mainstream is driven by Pete’s occasional use of a phase shifter in conjunction with his banjo. But Hot Rize stands firm—they play what they want to play. Pete addresses the situation by explaining, “Basically I have this motto: ‘If it sounds good, it must be good.’ The sound of the banjo through a phase shifter really appeals to me, but I’ve always tried to use it less than I could get away with rather than as much as I could get away with. It has offended certain purist people in bluegrass, although I’m gratified that quite a few people famous for being purists like it and tell me that I use it tastefully. When you get electronic gadgetry in there, there is a temptation to use it just as a gimmick, just to get a flashy effect, so I’m careful to only use it where I think it actually helps the music communicate better.”

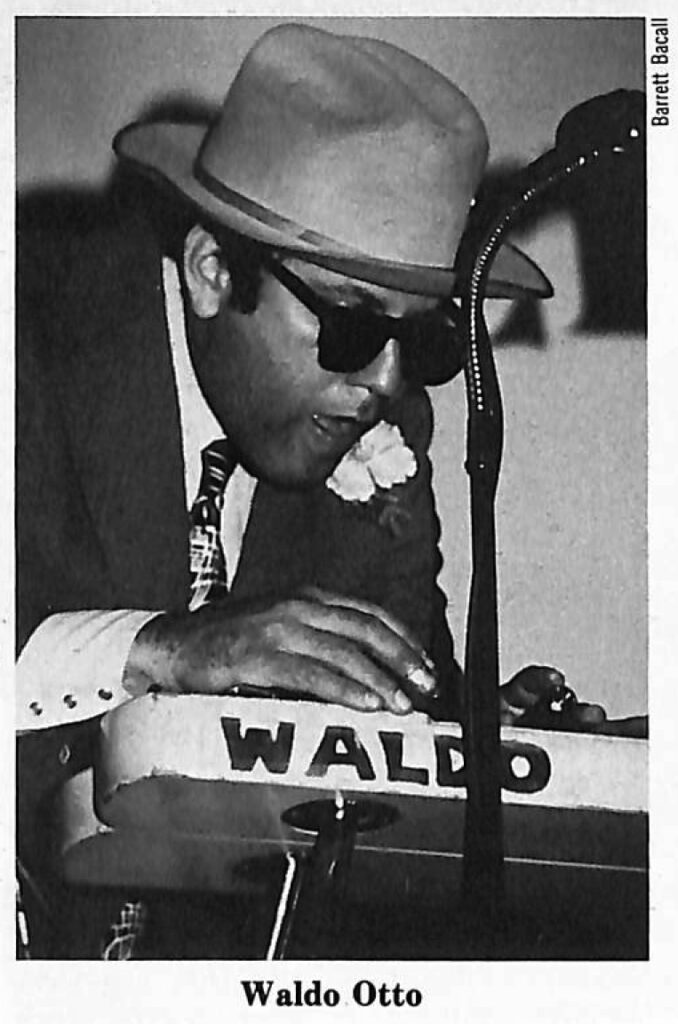

It is common knowledge that Waldo Otto, Red Knuckles’ steel player, is actually Pete Wernick. However, Pete is still unable to admit this where it might appear in print, and he even hesitates to discuss Waldo in public except to comment on Waldo’s inability to show up for gigs on time. Therefore, Waldo himself had to be consulted. When asked how he had learned to play the steel, Waldo responded, “You got to have a metal block.”

Pete Wernick has come a long way in the past twenty years, and working with Hot Rize obviously agrees with him. “I can’t tell you how proud I am that Hot Rize has weathered nine years together, and how fortunate I feel to have achieved my dream of playing in a band that gets to tour everywhere, a creative band with a lot of talent that loves traditional bluegrass. It’s a real challenge to try to play the kind of banjo that works in the band. It needs to be solid and driving, creative but not too intellectual, good tone, just generally polished. I give high priority to keeping up with my practicing, considering the demands of the job.

It’s a great musical opportunity. Also, I’m looking forward to improving my singing and getting more of my songwriting into the band.”

Teaching banjo is still very much a part of Pete’s life, although he now prefers teaching groups rather than individual students. In 1980 he began giving five-day banjo workshops in Cannon Beach, Oregon as part of the Haystack summer program sponsored by Portland State University. In 1985, these banjo workshops expanded to include all four members of Hot Rize, with the entire bluegrass band as their emphasis. In the winter of 1984/85, Pete added his annual “Winter Banjo Camp” in Niwot, Colorado, which “Dr. and Nurse Banjo” host on their own and which is attended by banjo players of all levels of ability from all parts of the country. Always in the back of Pete’s mind are the uncomfortable memories of his first stumbling years on the banjo and the lack of such things as tablature books, Music-Minus-One records, and instructional videos. “I’m gratified to think that there are going to be people who will actually succeed in learning how to play the banjo thanks in part to my teaching and the availability of this material. I love to teach person-to-person. It really excites me to hear someone’s sound come alive based on some suggestion I’ve made. I like interacting with banjo people, and I use what I learn in the situation to improve the teaching materials I’m working on.”

During the summer of 1986, Pete was approached by the board members of the newly formed International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) to run for the office of IBMA president. “At first, all I could think of was ‘How can I make time for this?’ But at the same time I felt extremely honored to be considered for the position.” A few months later Pete was elected. “It took a while for it to dawn on me: a Yankee, the first president of the IBMA! But I have twenty-five years of gut-level involvement with bluegrass in a lot of different roles, so I’ve tried to draw on my varied experiences to do what I can for the organization. I feel the time is right for the IBMA and it can do a great deal to help bluegrass music. I hope a lot of people will get behind it and make it grow.”

These days, Hot Rize’s rigorous touring schedule requires Pete, Charles, Nick, and Tim to take longer and more frequent respites in Colorado where they can spend time with their families. Pete still uses much of his free time shuffling his future projects from back burner to front burner and back again, but now there is more time for Nondi and their four-year-old son, William, for installing skylights in their “solar room,” and for writing music and books. There is time, too, for donning a pair of headphones and sitting down with his banjo in front of a microphone and tape recorder, Earl Scruggs blaring in one ear and Pete Wernick blaring in the other. “I still work real religiously when I practice going after certain sounds that Earl Scruggs got: the smoothness and the clarity and just the drive and the great timing, all those things. I think any banjo player could learn a lot by aiming for that sound. And to this day, with all the incredible licks that people do come up with on the banjo, Scruggs is still the guy who has succeeded most in communicating the sound of the banjo to the rest of the world. There are some players that the average person won’t understand but other banjo players will flip over, whereas Scruggs played the kind of music that everybody could flip over. For me, that would be the ultimate musical goal.”