Home > Articles > The Artists > Pete Wernick

Pete Wernick

Dr. Banjo Turns 80

As a kid growing up in the Bronx in the 1950s, Pete Wernick lived within a subway ride of Yankee Stadium. For 75 cents, he could get a seat in the bleachers and spend an afternoon cheering on his heroes — Mantle, Berra, Whitey Ford, et. al. While he did play sports, he leaned more toward academic rather than athletic pursuits. But there was something about the team concept that would not only influence but also guide his thinking throughout his life.

Being from an academic family, young Pete could have easily excelled in any number of careers, and, in fact, did. Journalism, sociology, psychology, statistics, and teaching were all within his grasp, and they all played—and still play—a part in his life. But he took the road less traveled, and that path and passion led him to music. Not, as one might suspect, being from New York, to classical or Broadway or even Harlem hot jazz, but to a form so obscure that, for a while, he was unable to find anyone with whom to ply his newfound craft—bluegrass.

Now, the Bronx and Harlan, Kentucky, or the hills of old Virginia, might be a million miles away in a million different ways, but phonograph records did exist in the 1950s. So did radio. Pete’s dad, a mathematics professor, had an old banjo gathering dust, and Pete became enamored with it, spurred in large part by his discovery of Earl Scruggs. A friend had a guitar and showed him how to match banjo and guitar chords enough to play a few folk songs. Pete devoured Scruggs’ recordings, saw him play whenever possible, and slowly figured out its mysteries.

At 16, Pete enrolled at Columbia, where he eventually earned a Ph.D. in sociology, and all those forces—absorbing and playing music, spreading the gospel of bluegrass, and developing a way to turn listeners into players—were starting to coalesce. He would jam on Sundays at Washington Square Park, where he met and joined an ambitious bluegrass band, the Orange Mountain Boys, and his first sociology paper was “The Sociology of Bluegrass Jam Sessions.”

In 1963, he landed a DJ job at the college’s small AM station. His bluegrass show was soon promoted to the school’s widely heard WKCR-FM, and his two-hour program became New York’s only bluegrass show in the 1960s. Remarkably, the show continues to this day.

“That gave me some notoriety being the only bluegrass DJ in the city,” Pete recalls. “Plus, I was also interviewing folks like Bill Monroe and Doc Watson. I went to the first bluegrass festival in Fincastle, Virginia, where I got to meet Carlton Haney, the great promoter. I think he appreciated having a New York DJ at his festival, and I got to hear and interview many of the founding fathers—Mac Wiseman, Don Reno, Jimmy Martin, the Stanley brothers; I even got Carter and Ralph to do a station I.D. for my show. I learned a lot from Carlton and got to know him over the years.”

Putting the Team(s) Together

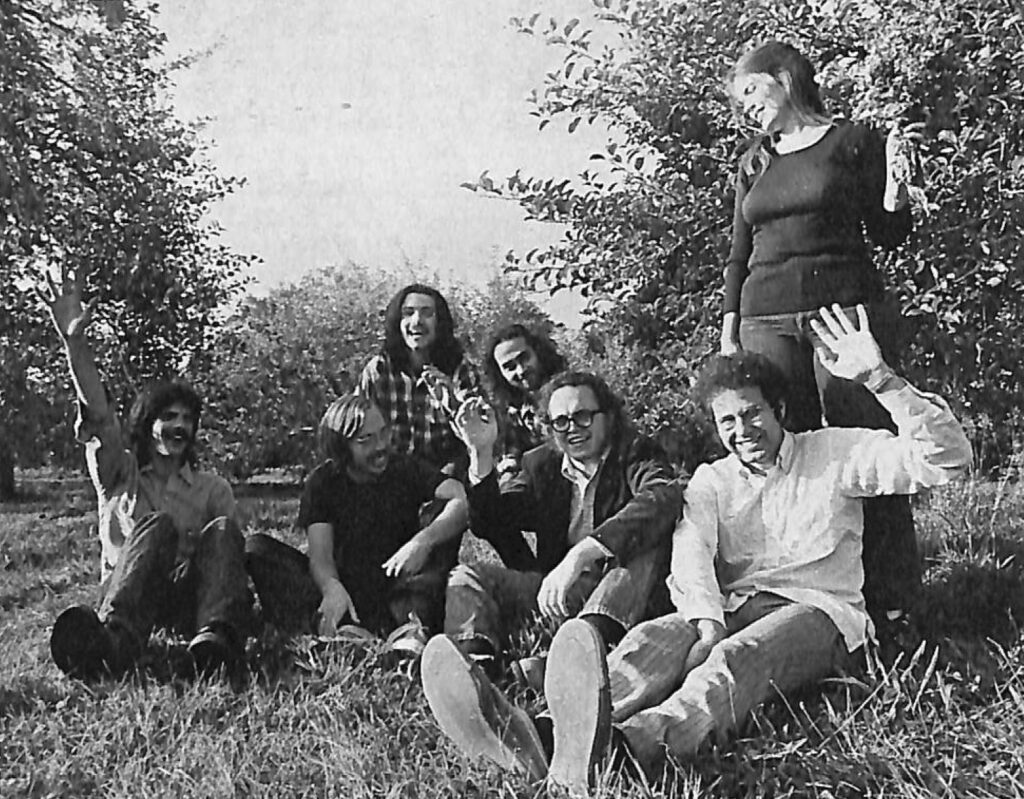

In the summer of 1963, the Wernick family temporarily moved to Palo Alto, California, where his father and colleagues were writing a mathematics textbook, and young Pete set out in search of some West Coast pickers. He found the bluegrass mother lode in a group of hippies who called themselves the Wildwood Boys. That name wouldn’t mean much nowadays, but its members certainly do—Jerry Garcia, Robert Hunter, and David Nelson. Hunter soon departed, and Pete joined with Garcia and Nelson to form the short-lived God-Awful Palo Alto Bluegrass Ensemble before Pete resumed studies that fall at Columbia. The members maintained friendships over the years, with Pete even guesting with Nelson’s band, the New Riders of the Purple Sage, years later.

“I got the benefit of rubbing elbows with some remarkable people before they got famous,” smiles Pete. Other picking partners and mentors at that time in New York City included David Grisman, Jody Stecher, and David Bromberg.

Back at Columbia, someone asked Pete for banjo lessons. Although he’d never taught, Pete agreed to give it a shot. So he wrote out dozens of tablatures, and his pupil learned to play them. Problem was, he couldn’t play anything that wasn’t written. And that’s what set in motion what would eventually become known as the Wernick Method.

“Tabs are simply reading what somebody else thought of,” he explains. “The way bluegrass is played is not so precisely exacting. It should be learned like a language, which is flexible, not like reading from a script. Tabs can block people from learning. I think you need to play with other people, learn the interactions. You can’t practice baseball by yourself; if you really want to play, you’ve got to be on a team.”

Pete went to work for Senator Eugene McCarthy’s presidential bid for most of 1968, but by summer’s end became disenchanted with politics. In 1970, he left New York and took a job as a sociology research associate at Cornell’s International Population Program in Ithaca, New York. There he met a group of radicals who would later form Rounder Records. That meeting would come into play the following year when Country Cooking, a group formed by Wernick, Tony Trischka, and Russ Barenberg, released an instrumental album that came to be known as 14 Bluegrass Instrumentals, Rounder 0006. “That album went all far and wide and helped establish us as musicians worth listening to,” comments Pete.

But he was also establishing a parallel career as a banjo instructor, and in 1973 wrote the book Bluegrass Banjo, followed in 1976 by Bluegrass Songbook. Combined, they sold over a third of a million copies and gave him enough income to quit his job at Cornell. He and his wife/singing partner Joan decided to move to her native Colorado, settling in the small community of Niwot, outside of Boulder, where they still reside.

Once in Colorado, Pete started teaching banjo at the Denver Folklore Center, where he met guitarist Charles Sawtelle. The two and Warren Kennison formed a non-commercial band that played Tuesday nights at the Folklore Center for two years, under names including the Drifting Ramblers and the Rambling Drifters

Armed with four Country Cooking albums and two books (and the moniker Dr. Banjo), he decided it was time to make a solo record. He had befriended Tim O’Brien and Duane Webster—from the popular Boulder group, the Ophelia Swing Band—and recruited them to play on the LP, Dr Banjo Steps Out. It was not your standard bluegrass fare, as Pete played banjo through a phase shifter on some tunes, and Jim Hoberman added a flute for a duet on “Whiskey Before Breakfast.”

Chuckling, Pete said, “In the late ’70s, being different was not all that different, because everyone was trying to be different. Breaking rules was typical, and that was my idea for being different.”

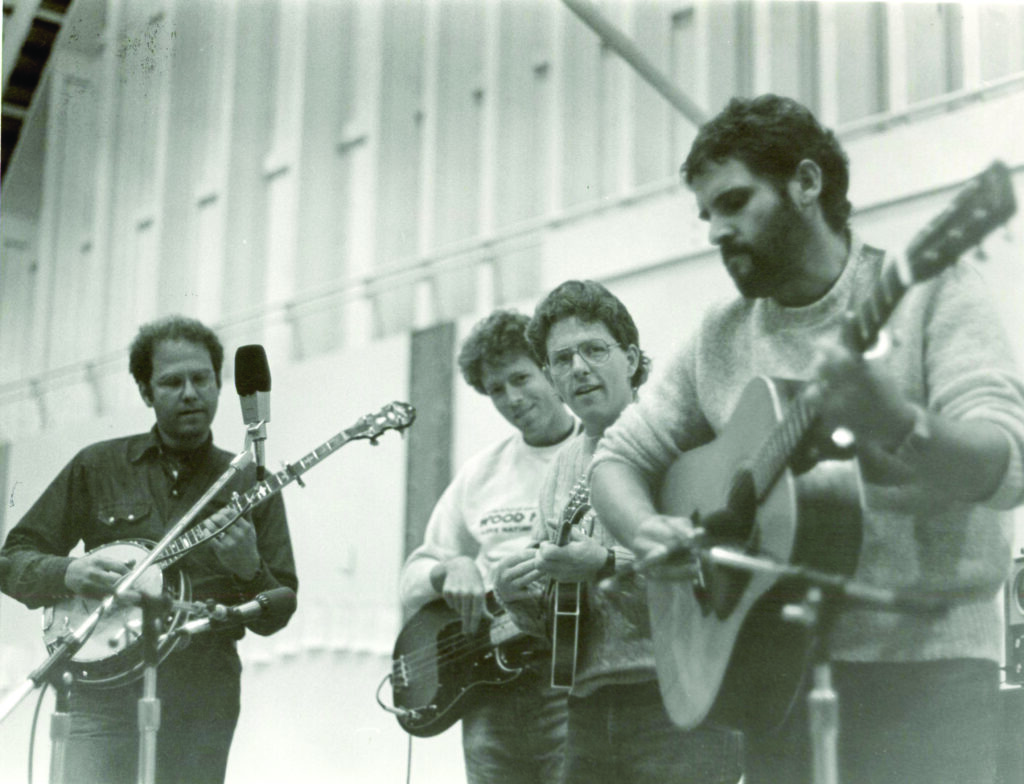

“Goodness Gracious it’s Good”

By late 1977, with the impending Flying Fish record release, Pete was ready to start a band to promote it. He called O’Brien, who’d moved to Minnesota, and asked him to come back and be the lead singer. Mike Scap, a guitar wunderkind who’d been on the demo for the album, agreed to return to Colorado from New Jersey, and with Scap on guitar, Sawtelle on bass and running sound, and O’Brien on mandolin, fiddle and lead and tenor vocals, the first incarnation of Hot Rize was born.

After a few months of breaking in the band and its new repertoire, Scap, reluctant to travel, quit the group, and Nick Forster, a talented and versatile musician and instrument repairman at the Center, was recruited to play electric bass, freeing Sawtelle to move to guitar. Forster took MC duties, and Wernick booked the band. The foursome played their first gig together on May 1, 1978, marking the start of the classic version of Hot Rize that lasted for two decades.

From the outset, there was something special about this quartet, aside from their obvious vocal and instrumental prowess. Pete, having followed Flatt and Scruggs, sponsored by Martha White Flour, suggested the name “Hot Rize.” The band readily agreed, which eventually became a merchandising bonanza. Sawtelle was a devotee of Goodwill stores and retro sensibilities, and the band followed his lead and began dressing in suits, Western boots, and vintage ties. They all sang into a single microphone, another throwback to the bygone days.

In the first year of the band, they caught the ear of Pete Kuykendall, publisher of Bluegrass Unlimited, and the magazine did a cover feature on them. The following year, they released their eponymously titled debut album, and in 1981, Radio Boogie, both on the Flying Fish label.

By now, they were becoming crowd favorites on the bluegrass festival circuit, pulling into the grounds in their 1969 Cadillac Sedan deVille (and later a Greyhound bus). Soon they were appearing on Prairie Home Companion, the Telluride Bluegrass Festival, Ralph Emery’s Nashville Now TV show on The Nashville Network, Austin City Limits, the Grand Ole Opry, and touring Europe.

The Hot Rize story would be incomplete without a hats-off to Red Knuckles and the Trailblazers, “the old-electric honky tonk band from Wyoming, Montana.” It started out as a bit of musical variety within Hot Rize sets, but took on a life of its own, with band members taking new names and, at Sawtelle’s suggestion, a costume change into Western attire. Tim was now Red Knuckles, Pete became Waldo Otto, playing lap steel, Nick was Wendell Mercantile on electric guitar, and Charles, switching to bass, was Slade. They always referred to their alter egos in the third person. Their humor was cornball, along the lines of Homer and Jethro or Riders in the Sky, but their music was as authentic and pure as anything Bob Wills or Hank Williams ever did. And the fans loved both the humor and the music.

“I told our agent, Keith Case, that we wanted to do a single,” says Pete, “and he said no, you should put out a whole record.” That proved a wise decision. All told, Hot Rize released 12 albums, including three as Red Knuckles and the Trailblazers.

Hot Rize (and the Trailblazers) continued to tour, record, and gain in popularity throughout the 1980s. Then, in 1989, everything changed.

Tim O’Brien had written two songs recorded by Hot Rize, “Walk the Way the Wind Blows” and “Untold Stories,” which were turned into country hits by Kathy Mattea. RCA Records started to court him as a potential solo artist.

That May they had a gig at the Sanders Theatre in Boston. During soundcheck, Tim received a phone call from RCA offering him a contract. After the show, the band had a meeting, and Tim suggested they stay together another year, during which time he would record the RCA album and disband about the time the record came out.

“None of us held it against him,” says Pete. “It was a shock but not entirely unexpected. It was a milestone to think the band I had nurtured for 12 years was going to be ending, and I was wondering what the future might bring. But there was never any animosity.” The four agreed not to mention this to anybody. They didn’t want to draw attention to the dissolution and didn’t want rumors to swirl or any negative publicity.

But on July 19, 1989, the public found something else to talk about.

Flight 232

Hot Rize was playing the Winterhawk Festival, and Pete decided to travel ahead to take Joan and their son Will to visit his parents near the festival. They’d been in flight about an hour from Denver to Chicago to connect to Albany when they heard a loud bang in the rear of the plane, and it began tilting erratically. The pilot announced that they’d lost the rear engine and would be making an emergency landing in Sioux City, Iowa. But what he didn’t say was that the engine explosion had damaged the rudder and severed all the hydraulic controls, leaving no way to control or slow the plane down or steer it except by adding thrust to either of the wing engines. In the next half-hour, pilot Al Haynes would become an aviation hero.

The DC 10 made 11 circles heading for the airport and tried to line up with the runway. During that time, the media had been alerted and filmed the whole episode. Finally, Haynes made his final approach. For a moment, it seemed that disaster would be averted, but then one of the wings touched, and then the front, and the plane began cartwheeling. It broke into pieces at over 200 mph, amidst a giant fireball.

![Pete Wernick & Flexigrass, 2005 in Denver. (left to right) Greg Harris, Kris Ditson, Pete Wernick, Roger Johns, Bill Pontarelli [all still in the band]. Photo by Joan Wernick](https://bluegrassunlimited.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Flexigrass-at-Civic-Center-Park-Denver-Enhanced-SR-1024x396.jpg)

“Suddenly it was quiet, and we were upside down,” says Pete. “I grabbed Will (then 6 years old), and Joan made it out. I was trotting down rows of corn with Will on my shoulders, afraid it was going to explode. It was surreal.”

This was the first commercial airline crash ever filmed in progress and played continually on national news. The band’s road manager, Frank Edmonson, checked with their travel agent and found that the Wernick family had been aboard the plane. Agent Keith Case got word and gathered friends to grieve the Wernick family, assuming the worst.

Pete smiles and says, “They were interrupted by my calling to say we’d made it. Needless to say, they were happily flabbergasted.” One hundred and twelve souls perished that day, while 184 lived to tell about it. Forty-eight hours later, Pete and his mates walked onstage at Winterhawk to a thunderous ovation. Pete was playing his former banjo, his 1930s Gibson RB-1, which Edmonson had retrieved by breaking into the Wernick house. Pete’s new Gibson Granada banjo was later retrieved, quickly returned to Gibson, and its damaged neck replaced. Years later, Pete wrote a song, titled “A Day in ‘89,” which he debuted at a reunion of the pilots and crew in Denver. “It’s about what happened that day, and making sure your relationships are in good shape, because as the song says, you never know when you might die.”

Instruction and Innovation

Even if Hot Rize had never existed, chances are that Dr. Banjo would be known around the globe as having taught more folks the intricacies not only of playing the banjo but playing with other aspiring musicians. Sure, there are numerous teachers, but before he developed his teaching methods, most of those students would never have learned to play or sing in an ensemble.

He organized his first banjo class in 1980 at the invitation of Portland State University. His friend Fred Bartenstein suggested that his method could be transplanted to Colorado. Indeed, in 1984, he launched the first banjo camps, and they flourished. In 1990, just before Hot Rize played their farewell show at MerleFest, festival director “B” Townes asked him to bring his banjo camp to the festival the following year. After a decade, Pete decided to change that banjo camp to the first bluegrass jam camp for all bluegrass instruments, with many others to follow.

“So many musicians, and not just banjo players, are closet players,” Pete says. “Jamming intimidates and bewilders them and I realized I could be of service to them. I’m not just about banjo, I’m about bluegrass.”

By 2010 Pete had developed the Wernick Method, and since then he and his certified teachers have conducted over 1600 classes in 47 states and 13 countries, with student registrations over 18,000. Naturally, he is proud to have been such a big influence on so many people, but there are a couple who stand out — Steve Martin and Chris Thile.

“I’d read in Banjo Newsletter that Steve was a fan of mine and Hot Rize,” he recalls. He met Martin in 2003 through their mutual friend John McEuen, of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. “He’d used the banjo in his comedy act, but to my surprise had never played with other people. He was reluctant to jam, but he wanted to learn. So, I organized a little jam camp at Steve’s home in Beverly Hills, with his neighbor Martin Mull on guitar. Steve was very diligent and caught on to it quickly, and had a good time. A few years later, Hot Rize played at his wedding. He’s a very gracious person.”

So gracious, in fact, that he and wife Anne, established the Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass in 2010 and have awarded more than $500,000 to banjo players. Pete is on his board, as well as such notables as Béla Fleck, Tony Trischka, Alison Brown, et al.

Pete remembers, “I first saw Chris Thile at a California festival when he was seven, and was already fluent, using all four fingers without looking,” he smiles. “The next year, I jammed with him, and he was amazing, already writing tunes. He was very sweet and unpretentious, just a happy, pleasant kid, who just happened to be a musical genius.”

At 12, Chris had written enough tunes for an album and asked Pete to produce it and play on it. He pitched it to Rounder and Sugar Hill, and Barry Poss of Sugar Hill jumped on it. Being an ardent Cubs fan, Chris titled it Leading Off, followed by Stealing Second, both by the time he was 16. Nickel Creek had already started when they were very young, and later he formed the Punch Brothers, both highly acclaimed and successful.

“His parents made sure he was a good person and not just a great musician,” said Pete. “We all still stay in touch, and Chris, now in his 40s, is a sweet guy, while continuing to amaze everyone.”

Still on a roll

While Hot Rize officially broke up on April 30, 1990, in a very real sense, they didn’t really. They won the first-ever IBMA Entertainer of the Year award that year and continued performing sporadically until 1998. Tragically, Charles Sawtelle died from complications of leukemia the following year, and the band went on a three-year hiatus. In 2002, they released the live So Long of a Journey, which they’d recorded in 1996 and picked up flatpick wizard Bryan Sutton. Two more albums followed: When I’m Free in 2014 and the 40th Anniversary Bash in 2018.

Yet, even as Hot Rize slowed down, Pete sped up. Elected in 1986 as the first president of the IBMA, he served for 15 years, until 2001. Around that time, he became friends with Earl and Louise Scruggs and had many long visits at their home until Earl’s passing. He recently came across a prized possession— a 90-minute recording of himself and Earl planning an instruction video (that unfortunately never came to be). In the 1980s and 90s, Pete wrote two more books, Masters of the Bluegrass Banjo, co-authored with Tony Trischka, and How to Make a Band Work.

In the 2000s, his jam camps continued picking up steam, with his Wernick Method becoming the international standard for teaching bluegrass jamming. And between 1985 and 2003, he produced 10 banjo and jamming instructional videos for Homespun with Happy Traum.

![Members of faculty, first Telluride Bluegrass Academy, 1988

(left to right) Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, Jerry Douglas, Mark O’Connor, Nick Forster, Pete Wernick, Pat Flynn [not pictured: Peter Rowan, Sam Bush, John Cowan, Tim O’Brien, Charles Sawtelle]. Photo by Joan Wernick](https://bluegrassunlimited.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/faculty-members-Telluride-Bluegrass-Academy-1988-1024x571.jpg)

(left to right) Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, Jerry Douglas, Mark O’Connor, Nick Forster, Pete Wernick, Pat Flynn [not pictured: Peter Rowan, Sam Bush, John Cowan, Tim O’Brien, Charles Sawtelle]. Photo by Joan Wernick

Of course, Pete has never stopped performing. His 1993 solo album, On a Roll, included his #1 original song, “Ruthie,” and around that time, he formed a new band: Pete Wernick’s Live Five, later renamed Flexigrass, an eclectic mixture with banjo, clarinet, vibraphone, drums, bass, and wife Joan on vocals. They still perform occasionally today. He and Joan have also toured worldwide as a duet, performing and teaching in Ireland, England, Scotland, Holland, Denmark, Israel, Canada, Czech Republic, and Russia. They will also appear at the 2026 MerleFest.

In 2005, Pete gained some national exposure, appearing on the David Letterman show with Earl Scruggs, Steve Martin, Tony Ellis, and Charles Wood, as Men With Banjos (Who Know How To Use Them), a name concocted by Pete.

Last summer, he was invited to a long-running event in France, the La Roche Festival, where he taught jamming and played with the popular jamgrass unit, Rapidgrass.

And that brings us to September 18, 2025. At long last, Hot Rize was inducted into the IBMA Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame. They performed “Just Like You,” a Wernick composition, and “Hard Pressed,” written by Tim O’Brien. Each member spoke, with Pete calling it “a dream I never dared to dream.”

Photo by Dan Schattnik

Before the ceremony, he mused, “As you live your life, the most important thing is that you feel satisfied with it, and for me it’s been a blessing. I’m so glad to be a part of the bluegrass community and all the associations I’ve had. I can’t imagine a better group of people. I have so much to feel fortunate about, and that makes me want to give back by mentoring people. When I think of the burdens some people bear, I realize how fortunate I am. I feel like this is where I belong.”

Yes, it is, Dr. Banjo. You found your home.