Home > Articles > The Archives > Pen Vandiver

Pen Vandiver

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1993, Volume 27, Number 12

During the summer and fall of 1991 while conducting fieldwork in the Rosine and Horton area of Ohio County, Ky., I found pictures and stories of Pen Vandiver scarce. One day an informant (anonymous) told me Vandiver boarded with the Clarence Wilson family for five or six years. After rattling through a bunch of papers in a bedroom drawer, the informant retrieved the telephone number of Flossie Wilson Hines, daughter of Clarence Wilson. The informant also suggested I interview Eba Wilson, Clarence Wilson’s daughter-in-law, from Owensboro.

The subsequent evening, I called Mrs. Wilson and arranged to interview her at her home the next day. After the interview Mrs. Wilson suggested we head to the garage to look through a box of old pictures once belonging to Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Wilson. The tattered, old, cardboard box contained several treasures: newspaper and magazine clippings, photographs, and several photo negatives. Quickly we rushed outside for sunlight. While examining the negatives, Mrs. Wilson exclaimed, “Why these are pictures of Pen Vandiver. Flossie [Wilson Hines] took these pictures with her camera.”

Although the negatives were splotched with mildew, Mrs. Wilson allowed me to have the negatives developed. The next day when I consulted several museum archivists about mildew removal, each archivist recommended developing the pictures with the mildew rather than taking a chance on ruining the film. Thus, I had the pictures developed; the mildew spots remained inconspicuous, except for scattered dark areas on the photographs.

Delighted with the pictures, I called Mrs. Flossie Wilson Hines and arranged an interview. Mrs. Hines gave explicit directions to her apartment in Bowling Green, Kentucky.

The trip to Bowling Green seemed unusually long because I was excited about hearing stories of Pen Vandiver: Eba Wilson had assured me that Flossie Hines would know a lot about Pen Vandiver. As I entered the driveway, Mrs. Hines left her rose garden and walked toward the car. “I shore am glad you come to visit me. Come on around back.” I trailed behind her, carrying a note pad and tape recorder. As we entered her apartment, she pointed for me to sit on the sofa while she sat in her chair. Flossie served as my key informant about the life of Pen Vandiver. Because she described Pen Vandiver the man, rather than Pen Vandiver the myth, her descriptive narrative acquainted me with her friend, Pen; and her stories thrust me amid colorful characters. Moreover, the passages reflected Flossie’s hard-earned wisdom as she described joys and sorrows of her rural Kentucky life.

Flossie Wilson Hines, second child of Clarence Remus Wilson and Minnie Cook Wilson, was born November 16, 1910, at the Wilson homeplace near Horton, Ky. Her family farmed 300 acres. The Wilsons’ firstborn, George Washington, suffered from brain fever; the local doctor examined George everyday of his short life. During her pregnancy with Flossie, Mrs. Wilson had further complications, and George died the week Flossie was born. Because of Mrs. Wilson’s poor health and her grief over her son’s death, Mr. Wilson hired an older couple to care for Flossie the first six months of her life. Although Flossie weighed only 4 pounds at birth, she grew in strength and led an active childhood until her school years. A few years later, Mrs. Wilson bore a son, Tommy.

Flossie, dressed in overalls, accompanied her father to the fields while he worked because she did not like staying in the house or doing household chores. When school age, she traversed cattle pastures and steep hills, sometimes wading through branches (streams). Flossie didn’t much like school. She contracted typhoid fever from the old well at the schoolhouse and missed many days of school. On the whole, Flossie preferred to stay at the homeplace with her father. At 18 she married Wavy Hines, then 27.

According to Flossie, Pen Vandiver and her father had been friends from youth. Before marriage and family responsibilities, the men played music together. Flossie grew up listening to her father tell stories of Vandiver and their wonderful friendship, and Wilson always spoke kindly of Pen as he reflected about their youth and their music.

During our first interview, Flossie Hines recounted the day Pen Vandiver and Clarence Wilson renewed their friendship. Flossie tended the animals everyday. As the sun began to set and she headed toward the barn, she heard someone in the yard:

“This old man rode up, and I was getting up the cows for Mammy to milk. I turned through the gate and saw some man on a big white horse. I thought, “Who in the devil are you? I’ve never seen you before.’ I opened the gate for him, and he came in, and he spoke and said, ‘Does Clarence Wilson live here?’ I said “He sure does, but he ain’t here right now. He’s a-cuttin’ wood. He’ll be in for supper. Mammy’s got supper waitin’ on him, and she’s a milking.’

“He came on in and said ‘I want to hide the horse.’ I said, “Well, you put [the horse] in the back end of the barn, and I’ll go get some corn for our team and the old horse.’ Well, I went and got [the corn], and he fed [the horse], and I put in feed for the mules so Dad wouldn’t mess around and find that horse. Pen said, ‘Now, I’ll come in and don’t you say nothing.’ Why, I said, He won’t know ye.’

“Pen came and knocked on the house, and Dad went to the door and invited him in. Pen looked at him and said, ‘Do you know me?’ He’d lost all his hair; he was bald-headed. And Dad said, ‘No, I’ve never seen you before.’ It was plum funny.

‘Pen said, ‘Oh, yes, you do: we bunked together; we made music together.’ [Clarence Wilson said], Not you, I don’t remember making music with you.’ Dad didn’t know who in the world it was. It had been so long since he had seen him. He hadn’t seen him since the last dance they played, and that was before he and Mammy married. Dad said, ‘Who in the world are you?’ Pen said, ‘Pen Vandiver.’ Well, I thought they never was going to quit and eat supper. We was hungry; we had worked all day. We set up all night long; we never got to sleep a wink. Pen said, ‘I’m going to see if that man’ll pay me, and I’ll be back.’ Well, Dad said, ‘Just come and stay if you want to. You ain’t got no place to stay. I’ll take care of you.’ He stayed with us four years.”

For the next decade Vandiver and Wilson worked and played music together throughout the region. During the interview Flossie described Pen, her treasured friend: ‘Pen used to tell on Dad. When they were young, Pen would come to the field where Dad was a-working’. Dad would be a-plowin’ corn, and he [Pen] said, Well, there will be a dance at so and so. Are you going?’ ”

“[Clarence Wilson] said, Yes, I’m going; wait until I get to the end, and I’ll put the mule out.’ He’d take the mule out, ‘n go to the house, and shave and take a bath and get ready and go.”

According to stories circulating in Ohio County, Pen Vandiver earned his living as a trader. Flossie heartily acknowledged Pen’s flair for trading in the community: “He was always outlooking for cattle, buying cattle or a hog. It didn’t make any difference, I said, ‘You’d buy a chicken, wouldn’t you?’ ”

Pen and Clarence [always got along together] Flossie recalls, “He and Dad never did have a cross word. They were jolly. Every morning [Pen and Clarence] just would get up like two boys going to play.”

Pen assisted Clarence Wilson in maintaining and harvesting the crops and tending livestock: “We all worked all the time like dogs, cuttin’ out corn, scrapin’ out tobacco, workin’ in the garden. Winters were awful, snow knee-deep, ice breakin’ trees in the woods, and sleet a-comin’ down. Water in the branches would freeze, and we’d have to break it for the livestock. We always had plenty of good food—killed-nine hogs in the winter, made two barrels of kraut, planted 200 pounds of potatoes, canned vegetables, and dried fruit.”

As a shrewd trader. Pen Vandiver, always had a cash reserve on hand. And because of his good-heartedness, he lent money too freely to family and friends. Thus, Pen appointed Clarence his banker. Flossie laughed as she recounted this story about Pen and his nephew Birch Monroe:

“Pen would have Dad keep his money. His relatives were always needin’ money. Birch wanted him to buy him a suit of clothes, and we got so tickled. [Birch] was goin’ with a Baize girl, and guess they were plannin’ to get married. Birch wanted [Pen] to buy him a suit, and Pen said, ‘Why, I ain’t even got a suit myself.’ Pen did not loan him any money.” Although the Wilsons knew Pen and his wife separated sometime after the death of their son, Cecil, they decided not to question Pen: “Pen’s son, Cecil, was a grown man and he died, got sick and died. I think he got pneumonia, and Pen and his wife was separated. They was broke, broke up like that. [Hines snapped her fingers, meaning quickly.] He never would talk about her. They had a daughter, too. I never would ask him about his [family]. It seemed like it hurt him to talk about it.” To supplement family income, Clarence Wilson raised extra hogs and cured hams for sale. People from the region soon knew Wilson for his hams and came to the Wilson homeplace specifically to purchase the tasty hams. Flossie recounted the day Arnold Schultz stopped at the farm to buy a ham.

“He came up there [to the Wilson farm] to buy a ham. We cured hams, killed enough hogs to have hams. A colored man came one day and bought a ham. I said, ‘Mr. Arnold, don’t you play a guitar?’

“He said, Yeah, you got one?’

“I said, ‘Yeah, play us a tune.’ Awh, he could just make it talk. Oh, he was the best thing you ever seen.” Arnold Schultz, son of David and Elizabeth Schultz, was born in the Cromwell area of Ohio County, Ky., in February 1886. According to the 1900 Census, Arnold could read and write. By age 14 he worked in nearby mines. A relative of Schultz stated that Arnold hoboed throughout the country by rail and river. Typically, Arnold Schultz left Prentiss (Ohio County) unpredictably, stayed away a few weeks or a few months, and returned with all kinds of new music. Then, he and friends picked and experimented with the new sounds. Soon, Schultz became restless, hung his guitar on his shoulder, and started down the road again. As a child, his relative (anonymous) remembers how Arnold Schultz left: he never said goodbye when he left on one of his journeys; instead he sat on the porch and played a tune, then began walking down the lane. When he came to a big old tree with massive roots above the ground, he sat on the roots and played a tune or so, then headed to another spot and played. After a few years of life on the road, Schultz stayed in the Ohio County region, working odd jobs, perhaps in the mines, and spending his spare time playing music with family and friends.

That memorable day—when Arnold Schultz bought a ham from Clarence Wilson—marked the beginning of a friendship whereby Clarence Wilson, Pen Vandiver, and Arnold Schultz spent hours playing music throughout the region. Little did anyone at the time realize the influence of these men on bluegrass music. Young musicians, such as Pen’s nephews, the Monroe brothers, copied or modified the sounds and techniques of these three men. The passing of time proved Wilson, Vandiver, and Schultz to be musical innovators whose legacy extends globally. Without doubt they created the seedbed for a new musical genre.

Flossie’s narratives demonstrate how frequently these three played music in the area. The Wilson family, including Pen Vandiver, spent many wonderful hours with Arnold Schultz:

“Well, an old man [this man is as yet unidentified] he had a car, and he’d go get him [Schultz]. He didn’t have no way to go, and this man would get him and we’d bring him with us. He’d eat after we’d done eat. I said, ‘I want you to eat now so we can clean and wash the dishes, so I won’t have to come in, in the morning, cook breakfast when there’s a bunch of dirty dishes. We’re going to the dance. Are you going to the dance?’

“Then [Arnold] said, I’m aimin’ to, if I got a way.’

“I said, ‘You got a way.’ People just worshiped him [Schultz]. He could play anything. He was short and fat. We told him he was eatin’ too much ham. He said he’d never been married, and lived around Prentiss.”

Arnold Schultz and his musical cousins, the Griffins, gave a big party for their friends, including Pen Vandiver and the Wilsons. Flossie Hines believes the party was a gesture of appreciation for the kindness the community in Ohio county extended to Arnold and his cousins:

“He [Schultz] had cousins, and they give us a party, a dance. We didn’t know [the party was for us, too]. We thought Arnold and them were goin’ to their dance. Arnold and them were goin’ to make the music, and it would end up we did the dancing and they did the waiting on us. Oh, they had mutton and all kinds of stuff to feed us. We had a ball. We got home at sunup. Awfulest crowd you ever saw in your life; they put down sawdust until it was nearly knee-deep. He [Arnold] had a ball, too.”

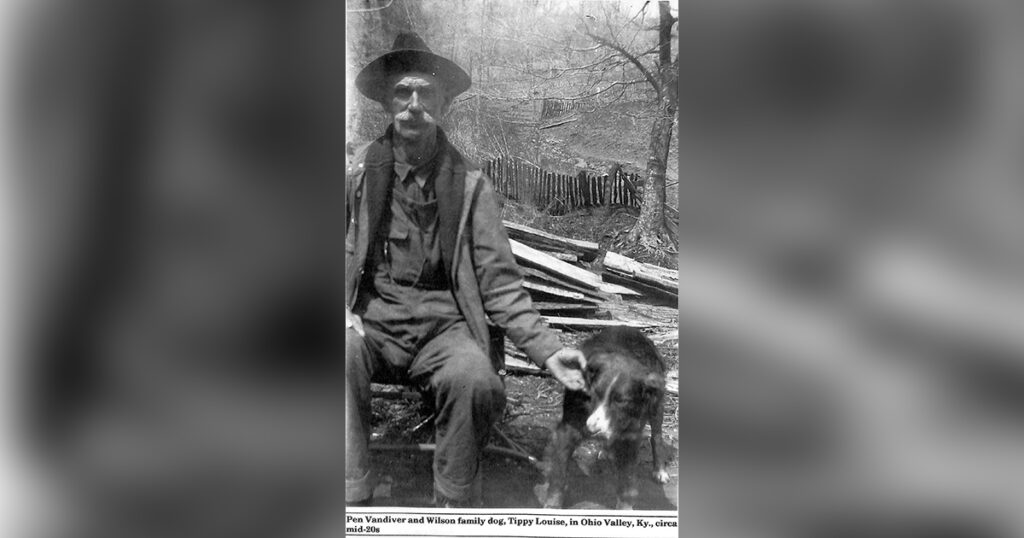

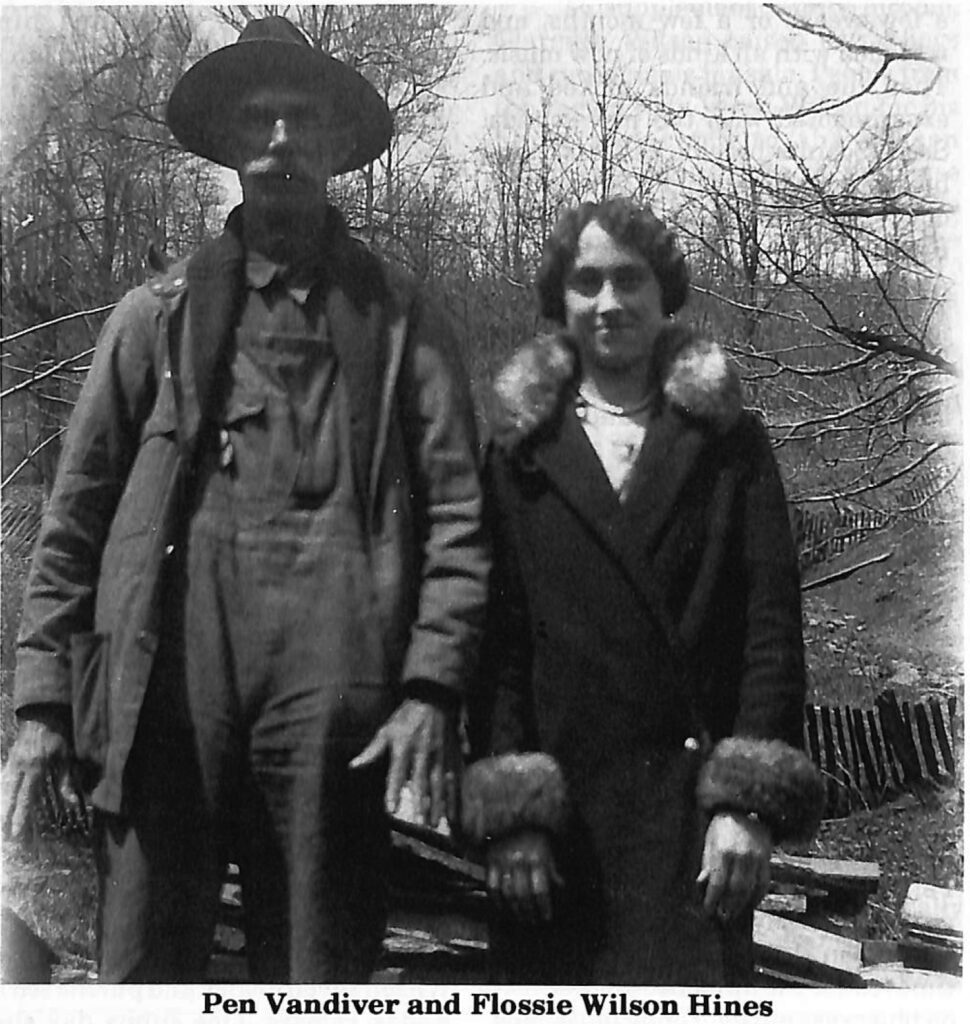

During her teen years Flossie Wilson saved money and purchased a Kodak camera. One sunny day she decided to shoot pictures of family and friends. In one of her favorite shots, Flossie captured Pen Vandiver and Tippy Louise, the family dog. (The Wilsons named every dog they owned Tippy Louise.) Someone else photographed Pen and Flossie. Recalling the day of these photos, Flossie comments: “They was sitting in the yard playing [music] when I took the pictures. I thought it would be a good time to get ‘em. I had one with Arnold Schultz. It took good of him, too; wouldn’t took nothing for the picture, you know. Show it to the grandkids. They don’t know nothing about what we use to do about dancing; everybody came to the dance and had a big time, too.”

Music provided a break from hard work in the hills of Ohio County. These people struggled to survive harsh winters and sickness. Moreover, as Flossie states, music relieved pressures in their everyday lives.

One day Pen Vandiver announced to Clarence Wilson that he needed his own place and began searching for a one-room cabin somewhere in the neighborhood. Although Clarence tried to persuade Pen to remain with the Wilson family, Pen located a vacant cabin and moved out. A few months later, as Pen headed toward the Wilson place, his young mule, startled by a train, bolted, leaving Pen and his fiddle on the ground. The mule had been to our house so much that it came to the gate. We knowed something was wrong; Dad found [Pen] laying there. His hip was broke. His leg never would set up no more. [The doctor] had to break it twice. It would just fall over, and he’d have to walk on crutches. He stayed at our house another ten months.”

Because his injury never mended properly and he couldn’t ever again put much weight on his hip and leg, Pen used crutches from the mule accident until his death. But after recovering at the Wilson place, Pen returned to his one-room cabin.

Later, during Pen Vandiver’s last illness, Clarence and Minnie Wilson looked after him, according to Flossie: “He got sick and Mammy and Dad and Dad heard about it and she [Mammy] cooked up a load of stuff and took up there. He had pneumonia fever, and he died that night.”

Arnold Schultz’s untimely death (moonshine poisoning) in 1931 and later, Pen Vandiver’s death (pneumonia) in 1932 marked the end of a significant era in American music. These western Kentucky men produced a rich musical legacy for coming musical greats such as Bill and Charlie Monroe, Mose Rager, and Merle Travis.

In his declining years Wilson continued playing music and telling stories about his wonderful time with Vandiver and Schultz. His daughter, Flossie’s jovial nature, expressive narratives, and photographs provide music fans and historians glimpses of their lives during an exciting era in Kentucky music history.

Sara McNulty Crowder is a folklorist and a freelance writer in Daviess County, Ky.