Home > Articles > The Artists > Open Up Your Mind & Free the Music

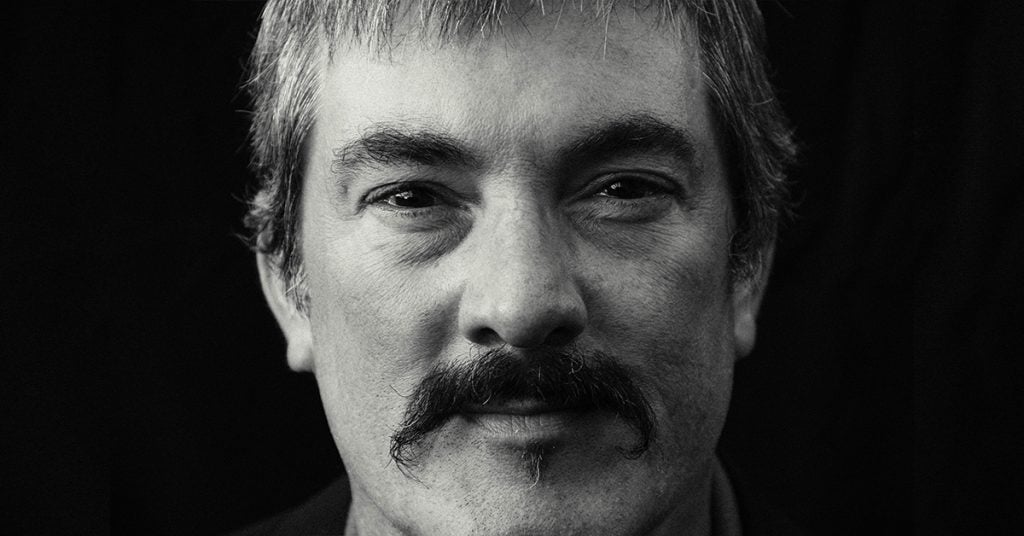

Open Up Your Mind & Free the Music

“For the first little while you have to find something to keep yourself busy,” explains guitar-wizard Larry Keel on how he approached the time at home forced upon us when the world shut-down due to the Covid-19 outbreak. “Even going to take the trash out was a big day in the neighborhood. It was something to do.”

For many, our days quarantined were filled with Netflix binges and baking bread. Thankfully, Keel found something more worthwhile to occupy his time than Tiger King, sourdough, and trash runs. “I spent a lot of time playing banjo, which is a big love of mine. In the process I wrote ten songs and I decided I would record them.”

Keel is best known for his revolutionary, Tony Rice-inspired, flatpicking guitar. But he has long explored the banjo and discovered just how far he could push possibilities on both instruments. For Keel, that exploration had always taken place in private. He had reserved his banjo playing for time at home and never shared those skills on stage. Keel has been inspired by some of the otherworldly banjo pickers who he has played with, including Mark Vann and Andy Thorn, who both logged time in Keel’s band before leaving to join jamgrass pioneers Leftover Salmon.

Keel was duly inspired by their creativity on the five-string. “All those crazy banjo licks I heard from them over the years are still in my head,” says Keel. “So I had to pick the banjo and sort of do my psychological training and get them out of there.”

When asked what he hopes to find while exploring the banjo in a deeper way, Keel pauses and laughs before answering, “I don’t know. I’m just working on my chops.” Keel’s wife and bandmate, Jenny, expands on her husband’s humble answer. “He wants to be confident enough to where he feels like he can just burn it down on the banjo. He wants to be able to really rip it up in a jam or on stage with his buddies, or with Leftover Salmon,” she says.

Over the past few years, Keel found he was gravitating more and more to the banjo when at home and working on new songs. “On our last album (2019’s One) I wrote most of the songs on banjo,” says Keel. “That is when it really started. I pick it up and things sound different to me.”

When the world shutdown in March, Keel was left with no obligations and nothing but time on his hands. The guitarist found himself inside much of the time as it was early March and a cold, wet, spring had descended on his home in the Blueridge mountains of southern Virginia. He holed himself up by the fire in his man-cave-shed with his banjo and some of his favorite movies like The Great Escape and The Guns of Navarone.

After twenty-five years of constant touring, to all of sudden see everything evaporate and have unlimited, undesignated time at home was a new experience for Keel. With this newfound free-time, he became completely immersed in music and the banjo in a way he had never done before. Jenny Keel observed this process and the inspiration that washed over her husband.

“I watched him try different melodies, patterns, licks, and motifs, and saw him create whole new songs, then get out the pen and paper and start writing lyrics. It was the quickest I have ever seen him go through this process. Songs were just pouring out of him.” Keel agrees that the forced had a positive impact on his creativity, saying, “I had some extra space to clear the brain and the songs just started coming out naturally.”

Inspiration surrounded Keel as he went deeper and deeper on his banjo journey, and he found new, untapped ideas to explore.

“I think I was playing banjo so much I was out of my comfort zone,” says Keel. “I am comfortable with a guitar in my hands. When I play guitar it is a whole different mindset. I know things that I do and it just comes out. When I play banjo, it is spontaneous. My brain works a little differently when I play banjo. It’s more a circular motion as opposed to an up and down one.”

Being out of his comfort zone sparked the songwriter in Keel and he was crafting tunes at a furious pace. He knew what he was doing was special and that he needed to record the songs he was writing. A studio was quickly set up in his home and Keel got to work. In the past, he might write songs on the banjo but eventually rework and record them on guitar. This time he wanted to play banjo on the album, as well. He took this notion even further and decided to play all the instruments that would appear on the album – banjo, mandolin, bass, guitar, and electric guitar.

“It’s a unique solo album like what Jerry Garcia did with his first solo album Garcia where he played everything (except drums, which were played by Grateful Dead drummer Bill Kreutzman),” says Jenny Keel.

The Jerry Garcia and Grateful Dead connection is an important one for Keel, as the discovery of their music was an eye-opening, watershed moment for the young guitarist. His background in music was mostly rooted in a traditional bluegrass sound. For Keel, the connection to Garcia was not as circuitous as it seems. Before his discovery of the famed guitarist, Keel had been deeply into the 1973 album, Muleskinner, which featured a number of regular Garcia collaborators, including Peter Rowan, Clarence White, David Grisman, and John Kahn. The forward-thinking approach of the album had captivated Keel and was beginning to influence his musical direction.

“I was way into that album because I was studying Tony Rice, Doc Watson, and Clarence White, at the time,” he says. “It was the progressive thing.”

Keel was raised in a musical household. His father was a banjo and guitar player who played bluegrass and classic country songs. His dad often had other musician friends over to the house for all-night picking parties. With his family’s influence and those late-night picks at his home as guidance, Keel says, “Music was in my blood.”

He started playing guitar at age six, when his father bought him one and taught him, “Wildwood Flower.” Since that day, Keel proudly declares he has, “Never set the guitar down.” Until he was sixteen, Keel mostly played bluegrass and the more traditional music that he heard around his house growing up. Then his friends introduced him to the Grateful Dead and heavy metal and his musical world was never the same.

“I was a bluegrass guy my whole childhood. It was all I really knew,” he says. “Then my friends were like you got to listen to Jerry [Garcia]. They introduced me to so many different things; Van Halen was big, jazz and blues. I became a big [Eric] Clapton fan, Stevie Ray Vaughn was big for me. It all influenced me in different ways. I wanted to incorporate all those things into my music. It sort of developed my own style.”

Those different rock sounds allowed Keel to find his own unique, innovative, voice in music. Even with all of those influences, his ultimate inspiration was the legendary, progressive, bluegrass, guitarist Tony Rice. “I just had a thing for his sound from a very early age,” remembers Keel. “Back then we would buy records at the local music store. I would take my allowance and buy Tony Rice records. I had to learn to play from somewhere, and I just learned everything he played. That’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to learn everything he played.”

Even with his admiration for Rice, Keel recognized the danger and limitations for a musician who adheres too closely to trying to play just like one specific musician they idolize.

“You can dig a hole like that as well, because you are not playing what’s in your head,” points out Keel. “You are just imitating over and over. Once you start branching out, that is when you find your sound. For me, it was listening to Jerry Garcia and Clapton and Van Halen that influenced me to get away from that sound I first discovered, to be able to find my own voice.”

Keel views his introduction to the rock-world as an important detour and discovery that had a long-lasting impact on his development as a bluegrass guitar-player. There are many purists who cringe at the thought of seeing bluegrass evolve from what they know and love—the bluegrass created by Bill Monroe so many years ago. Keel is not one of those people.

“Bill Monroe was the original alternative musician. Wasn’t he breaking the rules when he first started?” asks Keel. “He brought blues into his music and brought panhandle swing and mountain music and Irish music and made his music his way. And that’s great. He formed his style. What people should take from that is that we should form our own style. You can look at the mandolin players in bluegrass, does Sam Bush play exactly like Bill Monroe? No, but he honors him. Does David Grisman play exactly like Monroe? No, but he honors him. Enough of the whole rules thing. Get rid of the rules, open up your mind and free the music.”

The combustible combination of Rice’s influential guitar picking, the adventurous improvisation of Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead, the songwriting and rock guitar genius of Eric Clapton, and the hard-edge of Van Halen came together in Keel’s playing to create a one-of-a-kind sound that has seen Keel become just as respected for his innovative and flawless guitar as Rice is for his. For Keel the ultimate validation and complement of who he is as a guitar player came from Rice himself.

“I got to play with Tony Rice many, many times,” says Keel reverently, “and it was such a dear thing. He said he loved my style because I didn’t try to imitate him. It was very satisfying to hear that I had my own voice from my hero who is standing next to me on stage.”

All of those elements found in Keel’s musical DNA and his stated desire to, “Get rid of the rules, open up your mind and free the music,” are on full display on, American Dream, his latest album. That collection was crafted while quarantined at home and was born out of his growing interest and personal journey with the banjo. Keel was exploring and breaking musical rules on American Dream. But he also delves into a wide-ranging lyrical cornucopia of topics that were on his mind. He started this project while sitting in he what calls his, “peaceful, little, mountain abode,” on the album’s closing track, “Mars’ Cry.”

As he sat in the safety of his home while watching a world in crisis and he was inspired to respond the best way he knows, in song.

“It is a very special project,” says Keel. The album opens with the personally charged, “American Dream,” which reflects on his place in changing society. He sings, “I don’t want to grow up to be another angry white guy. Self-important and all wrapped up in a white lie. It’s best when I spread happiness around, not bringing everyone around me down. I don’t want to grow up in a world that’s filled with hate. I would rather look at our differences and relate.”

The album features some of the most introspective lyrics of Keel’s long-career. He sings of the damage we are doing to Earth and the environment on the plaintive plea of “Mother Nature,” laments long-lost friends keeping watch over him as cardinals in “Old Friends,” tackles society’s ills and the selfish, blatant power grabs of those in charge in the aggressive, politically-infused, “So Black and White,” while “Old Man Kelsey’s” is a contemplative, reflective look at life.

“The album is biographical, and the songs reflect the times and things that are inspiring me,” Keel explains. “They are songs of the time and my feelings on it. I’m trying to reach a positive outcome on this crazy situation we are all in. There are also songs inspired by watching children playing out in the yard and not knowing what is going and what these times are all about. There are songs about empathy. Songs about nature. Songs about family. A song about my brother. Songs about animals.”

American Dream is a special album for Keel. He picks up the banjo and discovers new avenues upon which to continue his life-long, innovative journey in bluegrass. The album still features Keel’s mind-bending guitar work, but his palate has now broadened with the addition of banjo to his musical arsenal.

American Dream lyrically explores the world and strange times around him, with words that are just as sharp as his guitar. It is an album that could have only been made in these crazy times. It is a defining moment for Keel and points to new directions going forward for the musician. Keel recognizes how unique and special the album is, declaring, “This is the most mojo-istic music I have ever put out.”