Home > Articles > The Archives > On The Road with Tony Rice

On The Road with Tony Rice

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 2006. Volume 40, Number 10

For several years, Tim Stafford (songwriter, guitarist, and vocalist for Blue Highway) has been working on the authorized biography of flatpicking guitar pioneer Tony Rice, collecting interviews with dozens of Tony’s peers and friends in the bluegrass community. In 2003, journalist Caroline Wright asked Tim if she could help with the enormous project. With Tim’s blessing, Caroline spent several weeks with Tony in 2003 and again in 2005, traveling with him to various shows and events, visiting him at his home in North Carolina, interviewing him in long sessions on and off the road. She also kept a journal of her experiences. A thread of this journal will be woven through the biography, providing a glimpse of the man whose music has profoundly touched the lives and influenced the styles of bluegrass lovers for over three decades. This is an excerpt from Caroline’s journal, a preview of the biography that is still in progress.

It’s a glorious Kentucky evening and the fireflies are everywhere. We take a country road through rolling green pastures and arrive at the festival (after a few wrong turns past crude signage) at Terrapin Hill Farm. The place is sweetly humble, reminiscent of the early days at the Rothvoss Farm up in Ancramdale, N.Y., where the Grey Fox Bluegrass Festival is held. The middle-aged couple manning the gate is friendly and polite. They must also be quite bored, as it’s nearing the end of the festival and nobody else is around. They tell Tony that they are very happy to see him.

After a bit of confusion in the twilight, we arrive backstage. As we do, we hear the kickoff to “Old Home Place.” “Boy, listen to that,” Tony says. “Ain’t but one guy in the whole world can make a banjo sound like that.” The New South is just kicking off its encore. When lead vocalist Ricky Wasson begins to sing, it’s a little bittersweet, like the IBMA awards show 2003 all over again, with the New South reunion.

It’s now a half-hour before Tony’s set is scheduled to begin. He unloads the monstrously heavy flight case containing his Santa Cruz guitar from his truck, carefully unhooking the bungee cords that anchor it to the truck bed. The hillside beyond the rough fence near the stage is covered sparsely with hippies and hillbillies and everyone in between. The performer’s area consists of a white tent with open doors on four sides. There’s a table covered with picked-over festival finger foods (grapes, brownies, and is that hummus?), an old Persian rug, an older loveseat, and an ancient floor fan which moves the heat from one side of the tent to another. It’s quite dark, but there’s no lamp and no festival staff to hunt one down.

When the New South comes offstage, Tony and J.D. greet each other warmly with a hug and a couple of hearty claps on the back—they haven’t seen each other for a while. There’s Ronnie Stewart and Dwight McCall from Crowe’s band, and Wyatt Rice, Bryn Bright, and Rickie Simpkins from the Tony Rice Unit. I am delighted to meet Ann Simpkins, whom I’ve interviewed recently. We say only a few words, and then there is a tremendous explosion outside. Fireworks! Annie and I race outside like children. We stand on the steep hillside and look into the bright sky behind the stage area.

It is a long and generous fireworks show. The promoters must have spent the money they saved on signage to buy some pretty sophisticated explosives. Ann and I can scarcely believe our luck. We look at each other every few moments, certain that the last big detonation must have truly been the last one, and we’re wrong every time and finally we stop anticipating the end, simply watching the sky with deep pleasure. I hear a guitar being tuned, little riffs quiet and distinct under the explosions, and I know it is Tony.

As the last twinkling sparks are absorbed by the night, Ann and I walk back toward the tent. Tony emerges from the artists’ restroom, a large port-a-john. “You’re on!” someone warns him. “They’ve already introduced you.” I see Bryn and Rickie scurrying to the stage.

I go into the tent and there, much to my amazement, is J.D. Crowe by himself except for a couple of older fans. They leave the tent and I am alone with him. I introduce myself quickly and shyly—I’ve interviewed him maybe a half-dozen times over the years, but always and only over the phone. He seems genuinely happy to meet me in person, and I am able to spend a few minutes with him, talking about a variety of topics—golf, old cars, rockabilly music, etc. He tells me that he thinks he’d have been a country singer if he’d had the voice. “Don’t get me wrong,” he says, “I love the banjo! But I never even listen to bluegrass music.” We talk about the perils of the road, and he tells me he found it very hard to drive long distances in short periods of time back in the early days. Like the rest of the world, J.D. seems amazed that Tony still drives to all his gigs, usually by himself. “Boy, that’s hard. I used to see critters that weren’t there, out on the road,” he says, shaking his head with memory, “and trap doors that would open up in the pavement.” He tells me he only plays fifty dates a year, and he’s cutting it to forty and asking for a little more money. He wants to retire and golf and go to car shows and not have to play music on weekends.

A half-naked hippie stumbles into the backstage area, now lit by an old table lamp. The hippie is young and elfin, has obviously consumed an excess of spirits, barefoot and smelly, and clutching a beer. Around his neck is an instrument strap; it’s been autographed in a half-dozen places. He asks me to take a photo of him and J.D. with his disposable flash camera. I do, but the flash doesn’t go off and it’s the last exposure on the camera. He rambles boozily to J.D. about some female relative who had loved the New South back in the earlier days. J.D. is gracious and sweet, even through his dismay—the boy is not in the best shape.

Finally he leaves, but not before hugging on J.D.’s neck a little. The musician is good-natured and sends him off with a few kind words. As the kid stumbles away, J.D. just shrugs a little. We talk for a few more minutes and he leaves to drive home, banjo case in hand, his aloha shirt bright in the falling darkness.

I go to the stage area. Diane Rice (Wyatt’s wife) and Ann Simpkins are perched on two ancient rusty chairs, the only ones backstage (such as it is). Anticipating the long drive back to North Carolina after the festival, I decline a seat and go to the front of the stage to take some photos.

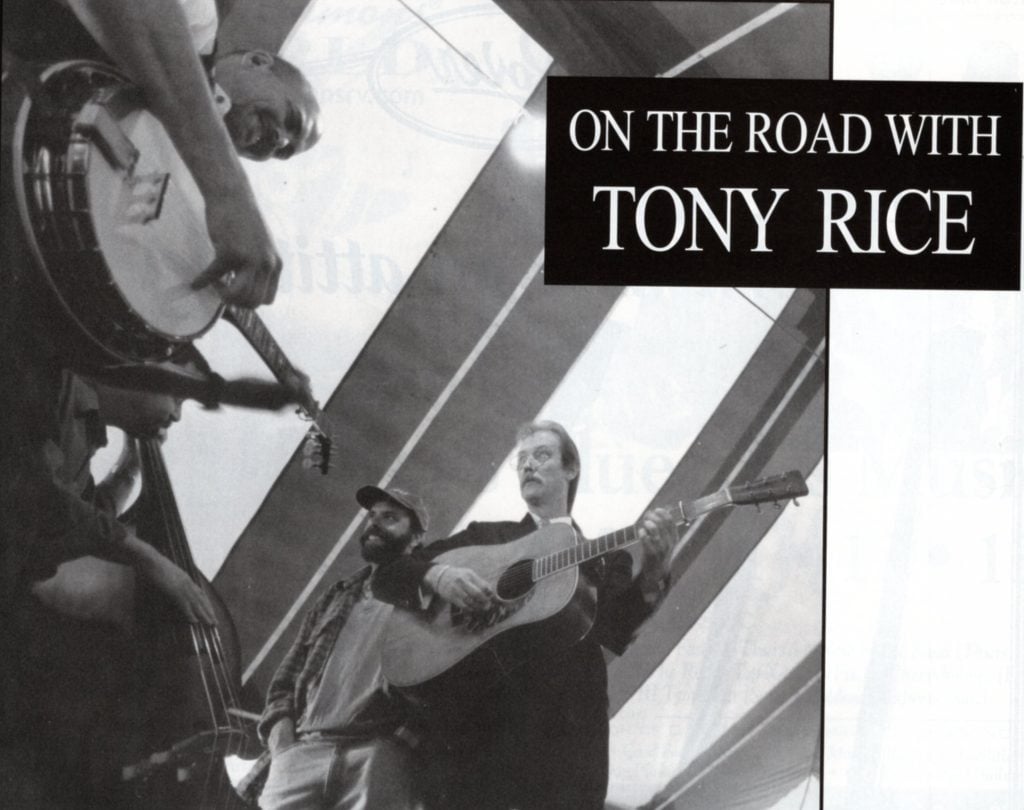

Onstage Tony is elegant, somehow removed from the rest of the world. As he transforms the guitar by giving it a voice when he plays it, it seems to transform him, too. He really doesn’t seem mortal at this moment. I take some photographs. This band, this configuration is so good— four musicians who weave in and out of their music with effortless grace. They play “Red-Haired Boy” and “My Favorite Things.” I notice with alarm that a small contingent of the crowd has become increasingly loud and obnoxious.

Then Tony introduces the next song, an instrumental version of an old Carter Family tune, “The Storms Are On The Ocean.” It’s a lovely tune indeed, and this version is as warm as an old friend’s embrace, but when the chorus comes ‘round, the sodden yahoos in front begin to bellow at the top of their lungs…off- key and unwelcome. Tony actually stops playing for a moment, glaring them into silence, or at least an acceptable din.

He and Bryn play “Summertime.” and it’s melancholy and wistful, with an outrageous bass solo. Their entire set is really extraordinary, the sort of thing that should only be played for a quiet, appreciative crowd. Perhaps, I think, the Unit should not have been booked as the evening’s last band.

Tony finishes his set and the bands exits stage left. “Let’s get out of here,” he growls, as he finds his way back to the tent. The yahoos roar for more, but there is no more. They’ve blown it. Bryn, whose bass is still onstage, makes a chopping motion with her hand in the direction of the sound techs—that’s all, folks. I would not want to be in her shoes for a million bucks, retrieving my bass from that empty stage in front of a legion of drunk and disappointed young people. But she does it gracefully with a sweet smile on her face. The yahoos boo half-heartedly, but they know better than to make an issue of it. (Later, I receive an e-mail from one of Tony’s fans who attended the festival. He tells me that some kid walked up to him while the Unit played and asked if that was Doc Watson onstage. He goes on to say that he was blown away to hear Tony play material off the CD he recorded with John Carlini [“River Suite For Two Guitars”]. “Tony may be surprised to know that there were some of us there that night who are very serious flatpicking students,” the fan writes. “We were beside ourselves to see him and Wyatt play that stuff up there.”)

The band moves to the tent. Slowly but steadily (one, then two, then a dozen), the fans come to pay their respects. Finally, Tony sees somebody who looks like a festival official. “Can my band just have five minutes of privacy in here?” he demands more than asks. “Certainly, certainly, of course!” the official says, and the fans obligingly move outside. One by one, the band takes its leave—first Wyatt and Diane, then Rickie and Ann.

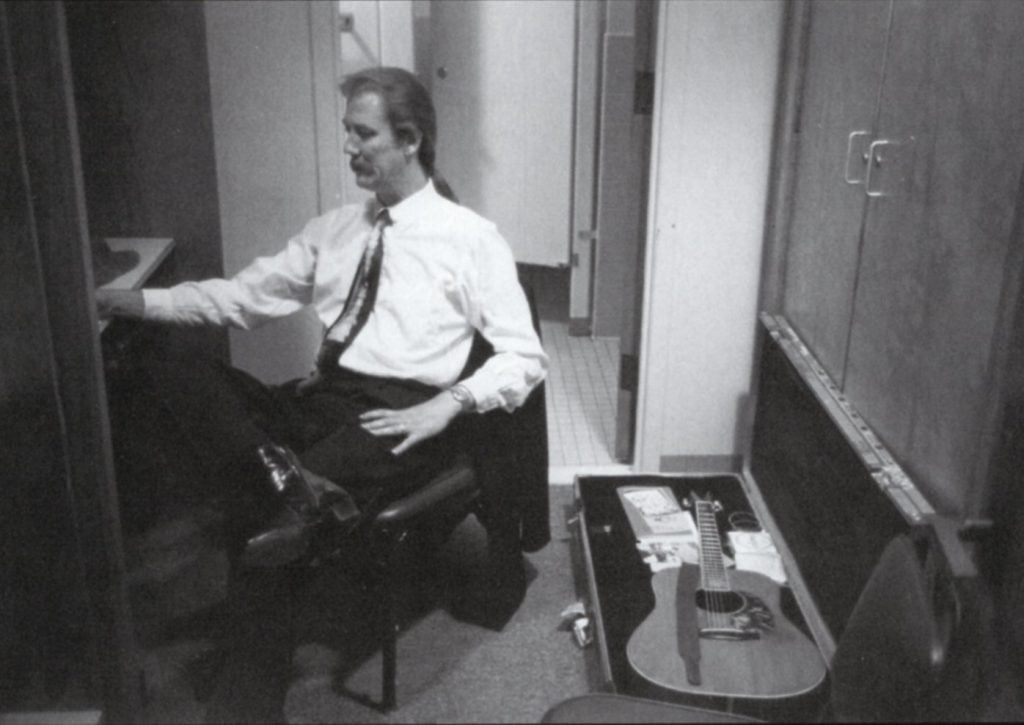

Wearily, Tony sits on the sofa and puts his head back. He has a peculiar flu that has affected the muscles and glands in his neck and shoulder. He must be in terrible pain. I see it etched on his face.

Bryn sits beside him, taking off her sandals and putting on socks and running shoes. They talk for a few moments. There are no chairs, so I sit on a cooler. Tony finally turns to me and says, ‘It’s a damn shame, because I really felt like playing tonight.’

We all share a few more words, and then it’s time to leave. He finds a bottle of water and drinks it down. Fans throng around one door of the tent, while we escape quietly through another. We load up the truck, trying to ignore the small disappointed crowd, and then we are moving on again, through the soft Kentucky night.

Caroline Wright is a freelance writer, living in Hawaii. She is the founder of Bluegrass Hawaii Traditional & Bluegrass Music Society (www. bluegrasshawaii. com .)