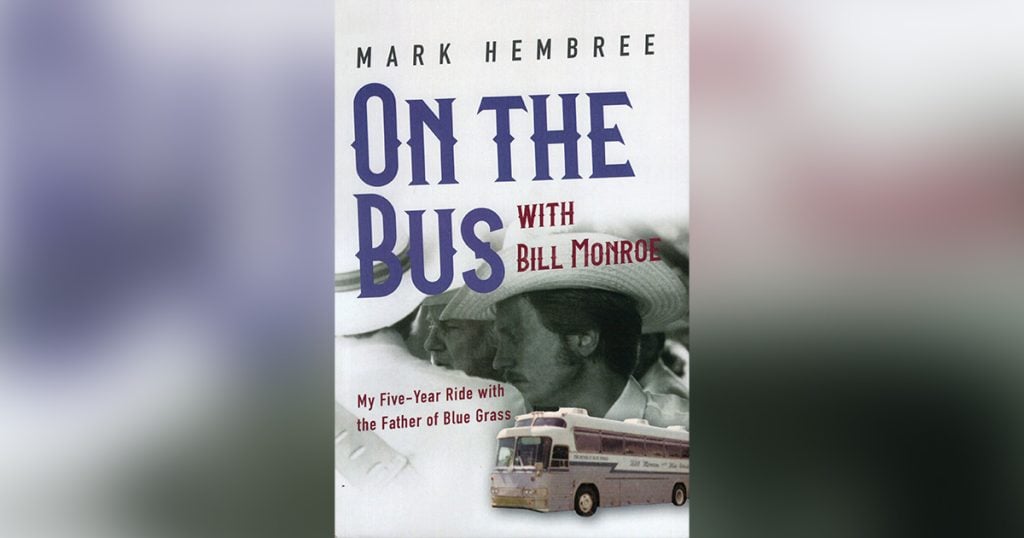

On the Bus with Bill Monroe: My Five-Year Ride with the Father of Bluegrass

Touring with Bill Monroe was notoriously difficult. Still, with Monroe’s foundational place in the history of bluegrass, it was a rite of passage that many musicians were not only willing but eager to endure. Monroe’s death in 1996 has of course shut the door to any future opportunities to tour with the “Father of Bluegrass.” Mark Hembree’s new book is about the closest any of us can now come.

Assembled partly from memory and partly from journals and other records Hembree kept while on tour with the Blue Grass Boys from 1979 to 1984, the tale is one that in many ways corroborates other accounts of Monroe and his ways. Hembree was lucky in that he joined the old master after he had been much mellowed by years and experience. By the time Hembree became Monroe’s bass player, the longtime bandleader had seen enough sidemen come and go to have gained at least an inkling of what it takes to keep employees happy.

Gone were the days when the Blue Grass Boys would have to go weeks and even months without pay. Hembree and his band mates—who included such luminaries as Kenny Baker and Butch Robins—were guaranteed $50 a day. But that was only for days when they played. Also gone were the days when Monroe was struggling against the formidable competition presented by rock n’ roll and commercial country. By the time Hembree joined the band, bluegrass was still being buoyed by the folk revival of the 60s and had found itself a reliable audience. Good gigs weren’t in short supply.

This is not to say that there weren’t hardships and frustrations. One source of dismay was a near total absence of communication about future shows. Hembree and his band mates regularly found themselves in the dark about when they would have to wake up on a given morning to travel to the next engagement. This was trying for a family man like Hembree, whose young wife would give birth to their two children while he was in the Blue Grass Boys. Hembree even found himself having to cut his honeymoon short so he could make a gig in Toronto.

Then there was Monroe himself. Though in his 70s, he remained a force. His icy stare, well-known and feared in bluegrass circles, could be summoned at will to inspire a deep sense of unease in its unfortunate target. A physically imposing man, Monroe seldom expressed displeasure through violence; the silent treatment was usually enough. Hembree learned this on one occasion when he declined Monroe’s request to drive his pick-up truck to Monroe’s annual Bean Blossom bluegrass festival. Monroe took the refusal as an affront. It was three months before he spoke to Hembree again.

Another time, Monroe insisted the band wear felt hats for a performance at The White House before President Carter and his wife. Hembree was then so short of cash, he was in doubt as to whether he could afford both the hat and his monthly rent. If his dad hadn’t wired him the needed money, Hembree’s journey with Blue Grass Boys would have ended much sooner. For the most part, though, Hembree stays away from the negative. He only hints at disputes with band mates. Gossip is scrupulously avoided. And there were compensations for the often unglamorous conditions of road life. Standing next to Monroe during shows and watching him work an audience were in themselves privileges. Even with his stoic demeanor, the man whom Hembree called “the boss” could command a stage just as easily as far more outgoing and conventionally charismatic performers.

Then there were the other musicians—most of all Baker, the “greatest fiddler in bluegrass music,” according to Monroe. Simply being around them was an education. Monroe was close to speaking a literal truth when he deemed his band a school for bluegrass.

Being a Blue Grass Boy was also a way to see the country and the world. Hembree, who grew up near Green Bay, Wisconsin, does some of his best eyewitness reporting when he tells of how alien he felt on his travels in the Deep South. Despite mass communications, the local dialect remained at times incomprehensible to his Yankee ears. One of his book’s many humorous touches is a glossary of the many terms and locutions Hembree eventually had to come to grips with.

Hembree’s time with the Blue Grass Boys led him not only through much of the continental U.S. but also Hawaii, Ireland and Israel. In the end, though, it was the constant travel, the demands of raising a young family and the opportunities presented by his founding role in the Nashville Bluegrass Band that drove Hembree to quit. His four years on the road with the Blue Grass Boys had vaulted him to a place of distinction shared by few others. He delivers his account of that time with the sort of lively, telling detail that can come only from someone who is reporting on lived-through experience. His book is a ride well worth taking.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Thank you, music lovers!

So how do I get it?