Home > Articles > The Archives > Ome Banjo Company

Ome Banjo Company

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December 1973, Volume 8, Number 6

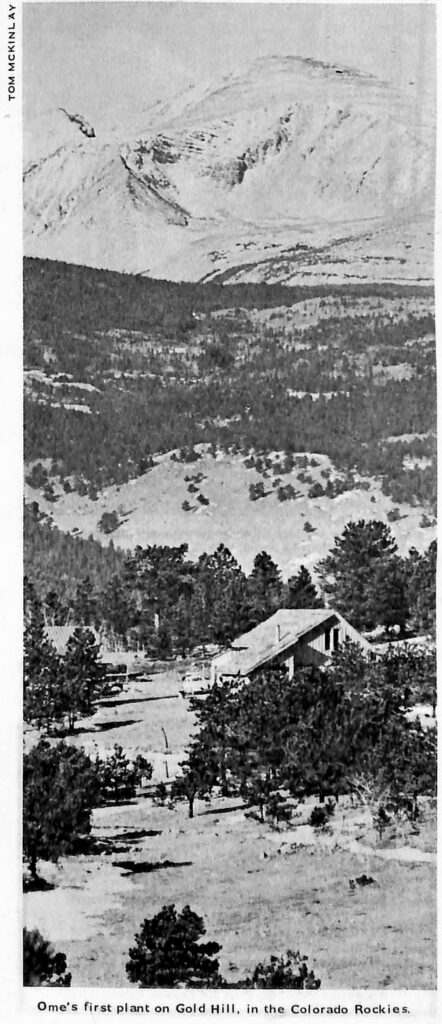

In the summer of 1971, four young men rented a mountain cabin fifteen miles northwest of Boulder, Colorado, high on Gold Hill, a snow-swept ridge overlooking the Rocky Mountain National Park. They had a panoramic view from their front door, but they had something else of more immediate value; they shared a deep-seated respect for old-fashioned craftmanship and a collective desire to produce a quality musical instrument. They gave their new partnership the name “Ome”, and began building banjos. Two years and over 500 banjos later, they’re going strong and the future looks bright.

It sounds deceptively simple. In actual fact, one of the partners, Chuck Ogsbury, started the Ode company in 1961; shortly thereafter, another partner of the present-day Ome company, Ed Woodward, went to work for him. They and a staff of a dozen or so made Ode banjos until that company was sold to Baldwin in 1966.

So the vital nucleus of experience was there. The other two partners, Kelley McNish and Ken “Antelope” Whelpton, had no experience making banjos, but both are musicians.

“We just got together and started doing it,” said Kelley, a 29-year-old University of Colorado graduate who is director of marketing and spokesman for the partnership. “We designed the instrument, and we’re continually revising it to make improvements on the original design, always working toward making a better banjo.”

Orders increased as the company’s reputation grew; the staff increased to seven, and this summer the Ome company left its idyllic mountain cabin for new, spacious quarters in a concrete building on the eastern edge of Boulder.

“We outgrew the place,” Kelley explained. “We were falling all over each other. Also, the trucks wouldn’t deliver up there, and we were losing a lot of time running up and down the mountain.”

By making the move, the company was able to triple its production. They made 90 banjos their first year, and twice that number the second year. They hope to produce 750 in the next 12 months.

Noting the similarity of the “Ome” name to “Ode”, Kelley explained the choice. “We wanted to maintain an identity with historic aspects of our experience, which we are legitimately laying claim to.” Besides two of the original partners, others on the Ome staff worked for Ode when it was in existence and operating in Boulder.

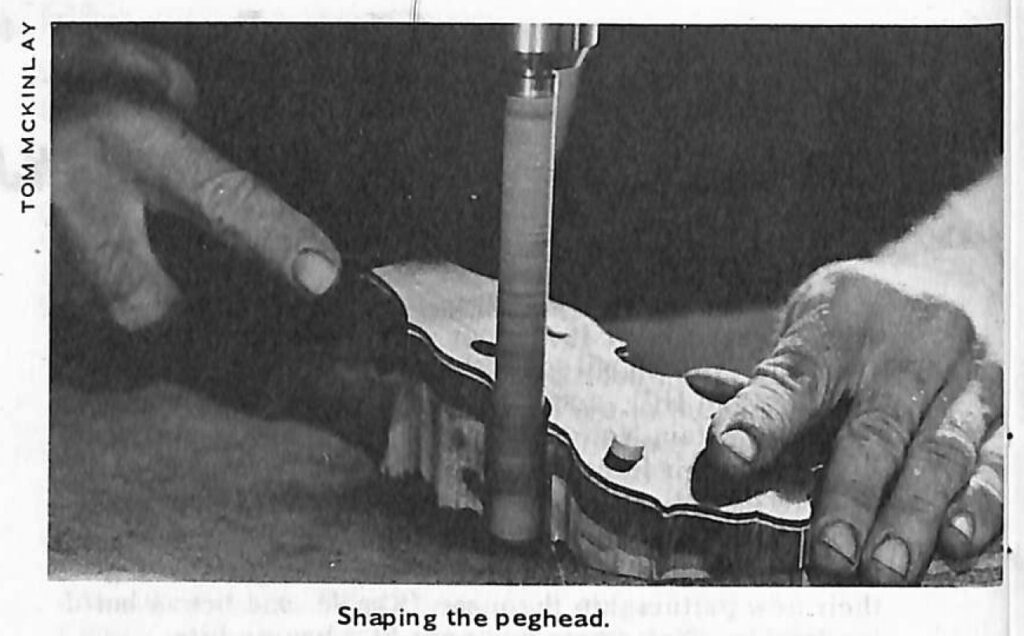

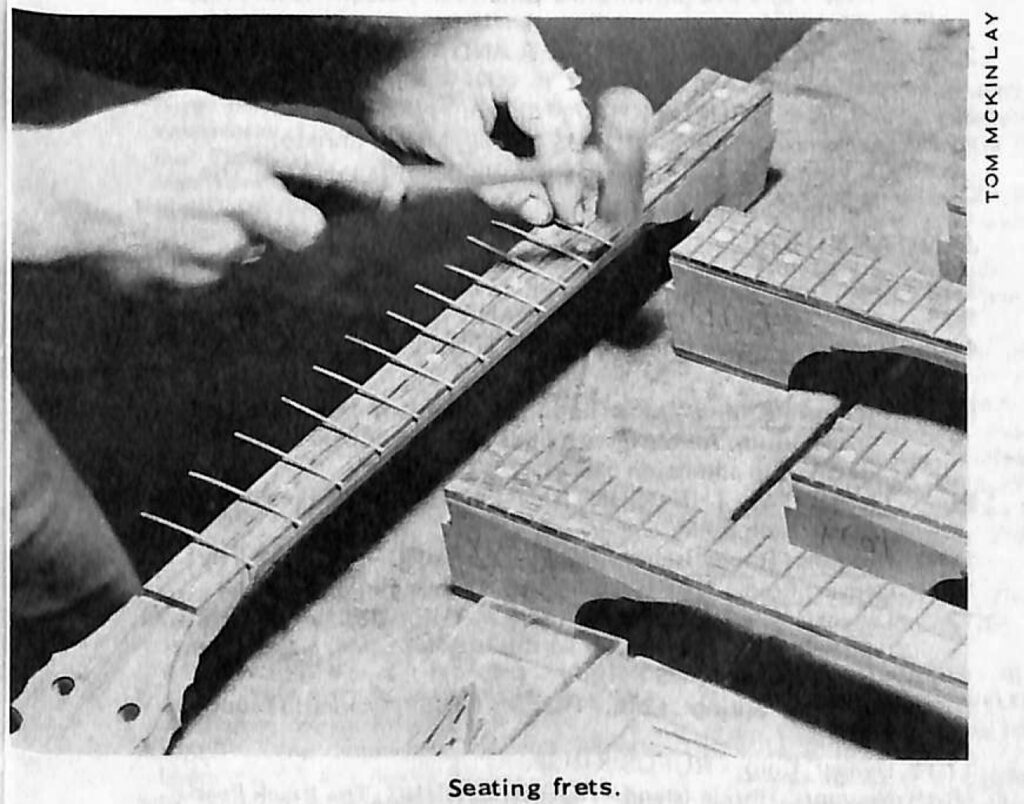

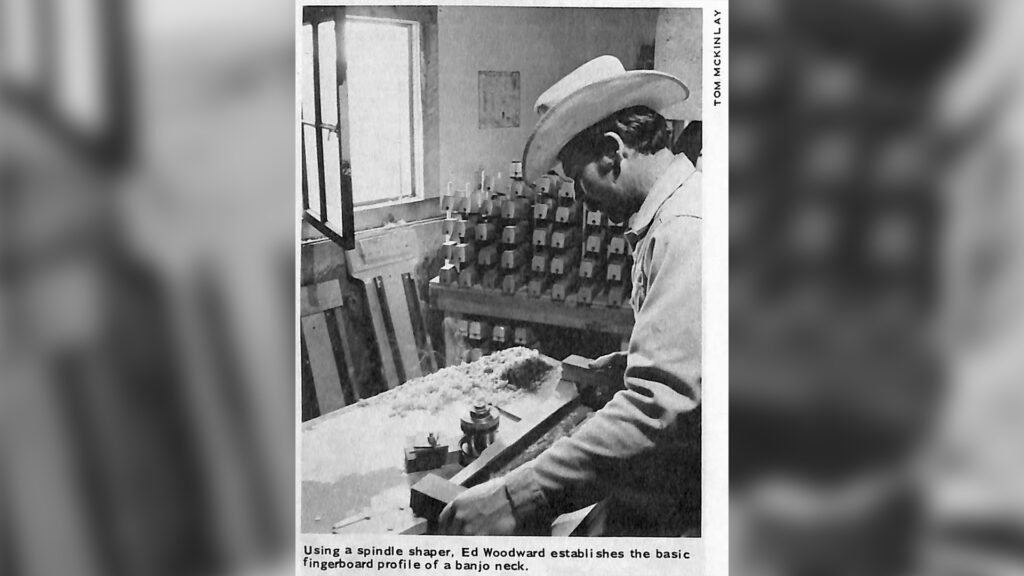

Chuck Ogsbury, while remaining in the partnership, is no longer involved with the actual construction of banjos. The other three continue to work closely together in the maintenance of the company. Ed Woodward is the general production manager, and also does all the milling. He can convert 40 board feet of South American mahogany into 18 or 20 necks, complete with pegheads. Kelley McNish, in addition to his job as director of marketing, does the post-milling operations on the necks. He is responsible for the fretting, carving, binding and finishing work, and also finishes rims and resonators. Ken “Antelope” Whelpton is the purchasing agent for materials, and assembles the finished parts into the final product.

When Antelope puts a banjo together, he sets it up and insures that the bridge is in the right place, so that the intonation is correct, and test-plays it to make sure there are no sounds present in the instrument other than that of the vibrating strings. He gives each banjo its serial number, representing its chronological place in the Ome line.

“Any little thing that might have been off during the machining stage has to be corrected here,” Kelley said. “Oh, they’ll all bolt together, but they have to be adjusted so that each instrument is right when it goes out of here.”

Having each banjo “right” seems to be a primary concern. On a tour through the shop, the idea of quality was a recurring theme in each operation.

“We use the best materials we can get,” Kelley said. “Through importers, we procure mahogany from South America, rosewood from Brazil and India, and ebony from Africa. We get maple from this country. We use brass wherever possible in the metal parts, because we’re convinced that brass is a superior metal in terms of how it affects the sound of the instrument.”

Some of the operations in the making of a banjo are done outside the shop on a contract basis, such as the fabrication of metal parts. After milling and polishing in the Ome plant, these parts are sent out again for electroplating in nickel, gold, or chrome. “Here again, we don’t go with the lowest bidder,” Kelley noted. “We go to the people who are best to work with, who can supply the part the way we want it to be. Then we look at the price of the thing.”

“We make very fancy instruments and very plain instruments. They all enjoy an equal amount of attention in terms of the work that is applied to them. Obviously, the fancy ones have much more expensive materials used, such as pearl inlays and gold engraving, but they are all made carefully. All the necks are hand carved and hand sanded, and all the bindings are scraped down until you can’t feel a joint. All these things are done no matter what the model is.” In the costlier banjos, each part must be perfect.

Kelley picked up an armrest and pointed out a pinpoint-sized discoloration sustained in the electroplating process. It was still a good armrest, one which obviously would not alter the tone or playing characteristics of a banjo. Such a part might be used on a “Grubstake”, least expensive model in the Ome line, to hold down its cost without sacrificing its basic quality.

They make their own purfling for the models that have this feature. They use wood veneers (“We don’t use plastic because it shrinks!”) and hammer them into two glue-filled concentric circles that have been routed out on the back of the resonator.

Of the ten models in Ome’s catalog, all but the ‘‘Grubstake’’ have lacquer finishes. Each rim, resonator and neck receives eight coats of lacquer, and thorough sanding with fine-grit paper after each application. Following the final coat, each piece is rubbed with a polishing compound.

“By the way, it isn’t recommended that you put wax over lacquer,” Kelley cautioned. “Lacquer is much harder than wax. That’s why it has been in common use on fretted instruments—it’s hard and it’s fast; you can move your hand across it quickly.”

Kelley refused to take the bait when asked why he thinks Ome banjos are superior to those made by other companies. Ome enjoys a good working relationship with its competitors. As an example, Kelley recalled the time when the industry’s only source of bracket shoes suddenly cut off the supply. ‘‘That nearly put us out of business. It cost us $5,000 to have an initial run of those parts made. The tooling for the piece was $3,500. In the interim, the Gibson company supplied us with bracket shoes. They were in the same situation we were in, but they had a few parts on hand and they sold us some of them so we could stay in business. They also sold to the Martin company, so they could keep making the Vegas. It’s nice to have a relationship like that with the people in the industry.”

What makes a good banjo? What are the important features to look for? “I’m talking generally here, not just about our line, but I use the example of our ‘Grubstake’ to answer your question. This is the product of thought that we put into making a banjo that had all the basic features that render it a good, reasonable instrument. The fret job is good, the scale is right, it notes correctly. The neck is straight; the fingerboard is in one plane so that the action is right and it’s easy to play. The neck has a tension rod, so that it’s possible to correct any bow or warp that might occur. Necks are pretty strong, and this doesn’t happen as a general rule; but the tension rod is a good back-up system, so to speak. Frets should be removable because they can wear out over the years and might need to be replaced. The metal parts are important; we feel that brass is essential in order to have a good-sounding instrument.”

“It’s a combination of materials and the way they’re used in putting the thing together. We feel that if something is going to be made, it ought to be made right. A decent product, worth the buyer’s good money. We’ve tried to keep the prices as low as we can, and it’s still amazing how much money they do cost.” Ome’s prices range from about $350 for the “Grubstake”, up to about $2600 for the “Big Mogul” and the “Juggernaut III”, both of which are available by special order only.

The cost of a banjo, like its quality, isn’t altogether found in the high-priced, exotic woods, some of which are bought by the pound rather than by the foot. Nor is it in the cost of the metals, even when an initial tooling for a bracket shoe costs $3,500. Rather, it is material costs in combination with untold man-hours of meticulous scraping, sanding, shaping, staining, and polishing by hand, plus the added intangibles of patience and pride in one’s work.

It takes ten weeks to make a banjo at the Ome company. Production now averages about three instruments per work day, most of which are marketed through retail stores in 40 states. The company is presently three months behind on order. Some banjos are sold by mail or directly to people who visit the factory.

“We’ve had very few returns from dissatisfied customers,” Kelley said. “Every step down the line, we’re always keeping a close eye on what we’re doing, and the design of the banjo is such that it’s going to last a long time-beyond our lifetime, with reasonably good care.”

So, with wood shavings in their hair and sawdust on their shoes, the Ome craftsmen continue their work in the shadow of the Rockies, pursuing their objective of “an honest product, genuinely well-made.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Ask Ed Woodward about Dave Walden. He called me ‘Waldie’, and I called him a ‘maniac’, as he was from Maine.