Home > Articles > The Archives > Ola Belle Reed—Preserving Traditional Music Without Killing It

Ola Belle Reed—Preserving Traditional Music Without Killing It

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1983, Volume 17, Number 12

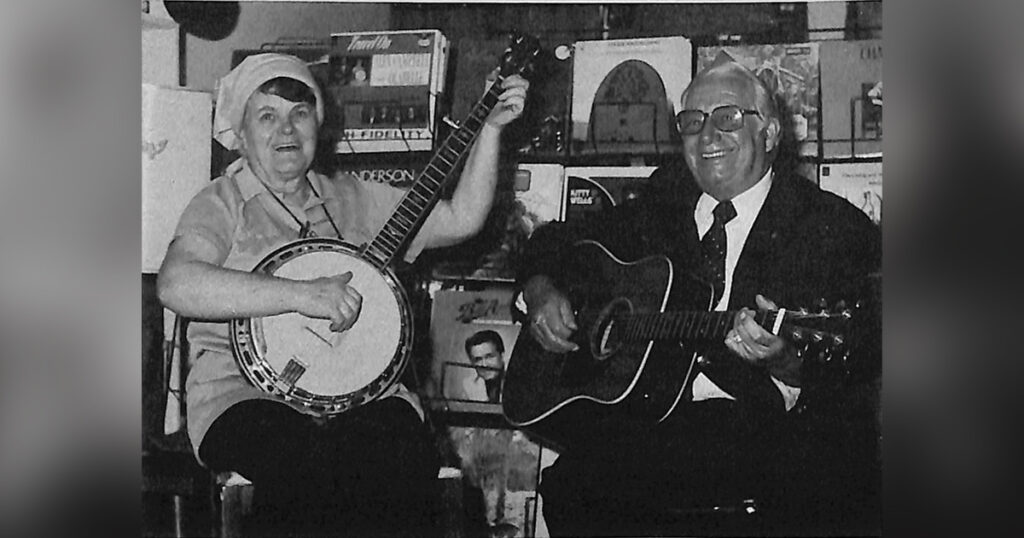

Ola Belle Reed has just completed a Sunday morning Gospel set with husband Bud and son David at the 1982 Brandywine Mountain Music Convention. She sits in the performer’s tent behind the stage resting, as her admiring fans come up to greet her and tell her how much they liked her show. A recent kidney operation has forced her to cut down the number of her performances and take it easy, but this Sunday she will spend hours talking to her many longtime friends in music, unable to tear herself away. If there’s anything Ola Belle enjoys more than singing and playing her guitar and banjo, it’s talking. She has lived a long time and lived deeply; and she has a lot to say. However, Ola Belle and her husband both possess the rare ability to practice what they preach. They have integrated music, business, and idealistic values in such a way that they live out their beliefs through music instead of letting music as a profession get in the way of living according to their values.

“We’ve never been prejudiced or jealous against any kind of music,” Ola Belle says in her deep, emphatic voice, a voice that conveys much confidence and conviction when she sings. “We’ve played the Great American Music Hall, we’ve played all kinds of places. I might not understand opera but I’m not ignorant enough to say it doesn’t have a place.

“Music is an international language,” Bud adds.

Ola Belle nods. “Yes. You communicate with people.”

“You can reach people with music,” Bud continues. “You can reach them through music. You can stand up and lecture a person all day, or you can sing a good song, and they’ll get the message.” Ola Belle is still full of emotion from a set that was well received. She gestures toward the stage. “You know what that is? A lot of people will think it’s maybe not me, that’s not what I’m thinking at all. But what I said up there is exactly true! The people, if you’re with them, they’re with you. They can tell it the minute you hit that stage. If you go out there they can understand exactly what you’re doing. That’s why I appreciate people the way I do. Because’ without people you don’t have it.”

The values that Ola Belle and Bud Reed are trying to communicate through their music come from Ola Belle’s own heritage, from her North Carolina mountain roots, that she has not forgotten. Often these values cannot even be expressed in words; it’s a love of people and a feeling for how we should treat one another. Ola Belle has dedicated her life to preserving the mountain songs passed on to her by her people and just this act in itself—preserving, not forgetting—is an example of one of her deepest convictions: you should not cut yourself off from your past, you should always be yourself. This concept also involves letting other people be themselves by accepting them for what they are and not judging them. She has carried this respect for tradition and for a person’s own culture throughout her long and varied music career.

Two events from her childhood instilled this belief and gave her the strength and endurance she needed to continue to be true to herself in spite of much ridicule for playing “hillbilly” music before the folk movement revived it, giving it some respect.

“I learned it from my grandfather back in the ’20s. My grandfather was an old mountain preacher with a long beard. He was just what he was. Honest, open. He was a person. He played the fiddle. A lot of people laughed at that and they were going to turn him out of the church. They thought instruments was a sin.” Ola Belle quickly defends their right to this, explaining that the church members were only following what they had been taught. “You see, if you’re taught something all your life, you may be ignorant of one fact, but that doesn’t make you an ignorant person.” It is clear that she holds no grudges against these people who, out of ignorance, not cruelty, made her very musical family feel like they were not good people.

“When they told him in the church, we understand you play the fiddle, he said ‘Yes, I do.’ And he was a minister, you see, and they told him, well, that was against the rules and regulations of the church. Where I got my strength was from people like that. Because they said ‘Well, do you have anything to say in your defense?’ And he said, ‘No.’ So, they turned him out of the church. And he said, ‘Well, now that I’m no longer a member of this organization I’d like to speak.’ And he stood up and said, ‘Now that you’ve accused me, by the same token you’ve judged me, which is strictly against the bible, judge not that you be not judged.’ And he said, ‘I’m not blaming you, but never again will I put my name on a man made denominational book.’”

Ola Belle’s grandfather, Alexander Campbell, never went to church again and continued to play and sing in his Ashe County, North Carolina home on Sunday mornings with his family. Singing and playing together, loving and caring for one another, became the Campbell’s nondenominational religion.

The other event from Ola Belle’s childhood which she will never forget is playing the banjo for a neighbor lady who did not laugh at her. She was used to being ridiculed for her banjo playing, but this woman actually listened and took an interest in something very foreign to her. She listened to the banjo playing and said it didn’t sound so bad to her, then asked Ola Belle to dance the Charleston for her. “They accepted me. She was trying to learn.” These people who had been taught that string music and dancing were evil were just “good old solid people with a good mountain home that would be worth a million dollars today, but they didn’t know that, and they wanted to know.”

This was Ola Belle’s first encounter with people who thought that their own mountain lifestyle was worth knowing more about and respecting, instead of being ashamed of it, and this spark of interest gave her the strength to continue over the years, preserving mountain values and culture through songs and music.

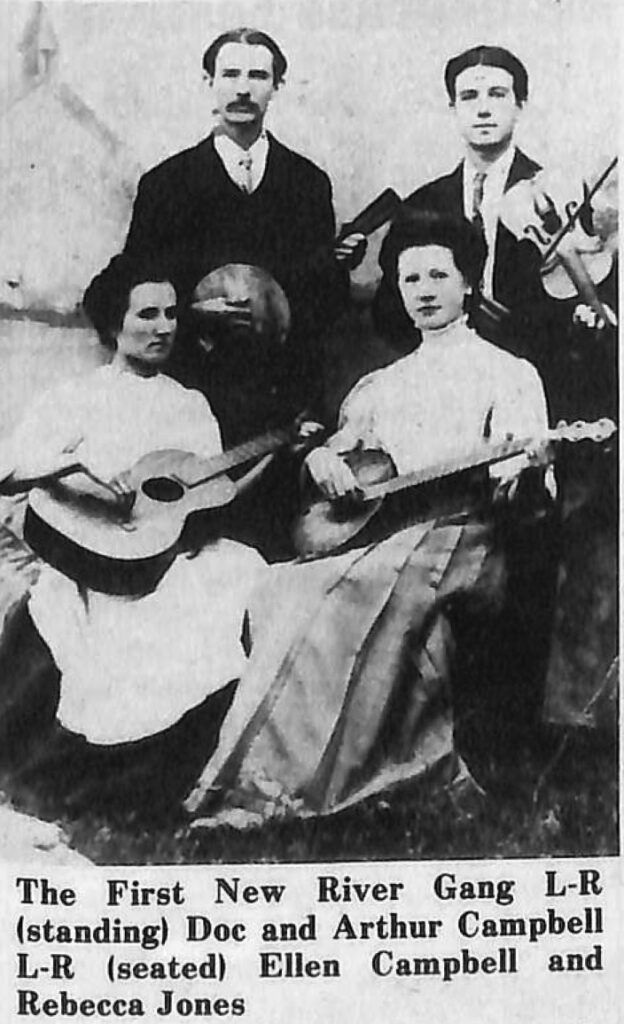

Ola Belle’s father, Arthur Campbell, played banjo, fiddle and guitar and started a hillbilly string band with his brother Doc and sister Ellen. Ola Belle’s grandmother and her mother, Ella Mae Osborne, were also very musical and passed along the words to many ballads that Ola Belle has not forgotten. Many folklorists and musicians will come to Ola Belle today for the authentic words to old mountain songs. Ola Belle herself has a doctorate degree in folk music, a little known fact that she doesn’t publicize. She studies folklore constantly to find facts that reinforce her belief that mountain music is rooted in rich European cultures and to give it the respect and dignity she has always known it deserved.

In spite of Ola Belle’s strong determination in preserving a music that was unpopular and ridiculed, she has managed to stay open to new musical forms, absorbing those parts of other people’s music that seemed natural to her own music, letting it change and evolve over the years, as her own life changed and evolved. Her parents moved their family of thirteen children to Northern Maryland during the depression after losing their store and farm. Many Southern mountain families also made this move during the same period because there was work on the Conowingo Dam and on Maryland and Pennsylvania farms. Here, Ola Belle and her brother, Alex Campbell, broadened their music through exposure to the diverse cultures of this area. They met other musicians who were playing bluegrass, traditional country, gospel songs, popular music, train songs, and New England music. Ola Belle and Alex got their first professional job with Arthur “Shorty” Woods and the North Carolina Ridge Runners. They played a variety of music in “hillbilly” style, at dances and carnivals. Arthur Woods got them on local radio stations and into the popular Sunset Park in Oxford, Pennsylvania. It was here that Ola Belle had her first date with Bud Reed.

Bud’s family were natives of this area and they were also musical. However their music was different from Ola Belle’s; mostly Irish folk ballads and country songs. Bud grew up playing harmonica, guitar, fiddle and banjo. His grandmother had an old Victrola, so he was exposed to popular country music through records. He developed a love of Jimmy Rodgers’ railroad songs from his grandfather, a railroad man, and from watching the trains at the Route 1 crossing in Conowingo, Maryland. However, he loved and was fascinated by the Southern Appalachian music that came from an isolated mountain culture where people had no record players and radios.

“My mom and dad would never hear of us making fun of anything or anybody. They wouldn’t tolerate that at all. I can remember when I played for dances back in the thirties, walking through the little town of Rising Sun, and all the people yelling ‘Yah-hoo’ and it didn’t bother me in the least. Because I loved it and I didn’t care if they liked it or not, because I knew a lot of people didn’t like it. But it was all I cared about. I just loved their music. I adopted their customs. I adopted their music but the first time I picked it up and started playing it, it became natural.”

Ola Belle and Bud married in 1949 and together they found a new form for promoting their music: country music concerts. In addition to performing with her brother in their new band, The New River Boys and Girls (a modern version of their father’s North Carolina string band, of the same name, with Ted Lundy on banjo, Deacon Brumfield on Dobro, and Sonny and John Miller on fiddles), Ola Belle now added the business of promoting to her musical mission. She and Bud ran Rainbow Park and then the New River Ranch, bringing on every Sunday for the next ten years such celebrities as Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers, Hank Williams, and a host of other bluegrass and country music stars. In the early sixties, they moved their show to Sunset Park, where Alex did emcee work and live radio broadcasts. Meanwhile, the New River Boys and Girls made appearances on WWVA in Wheeling and started making albums that sold well.

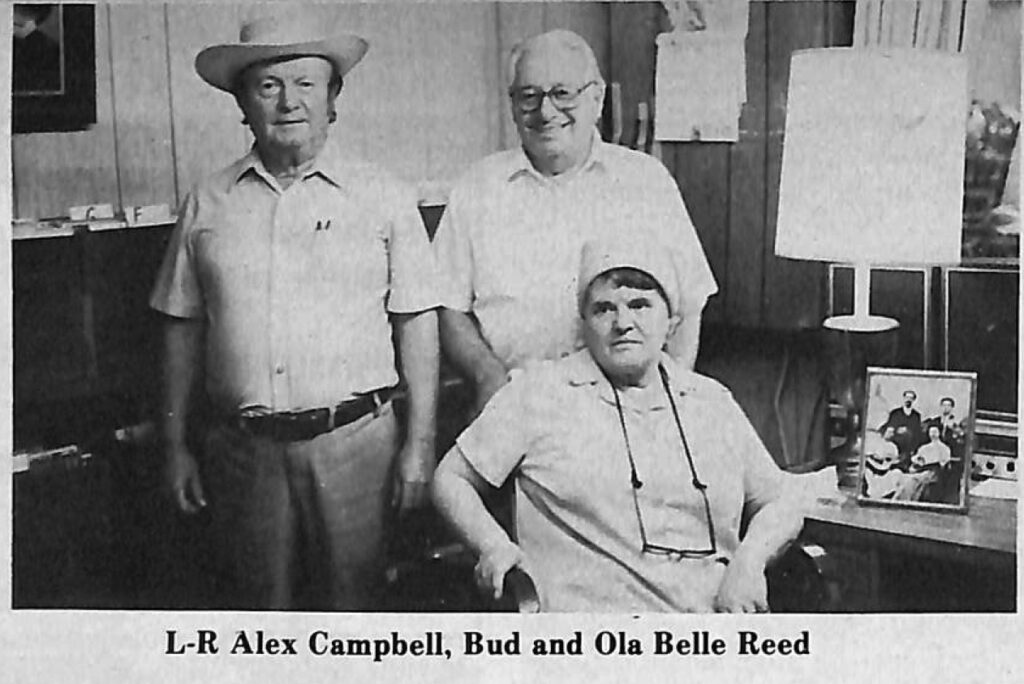

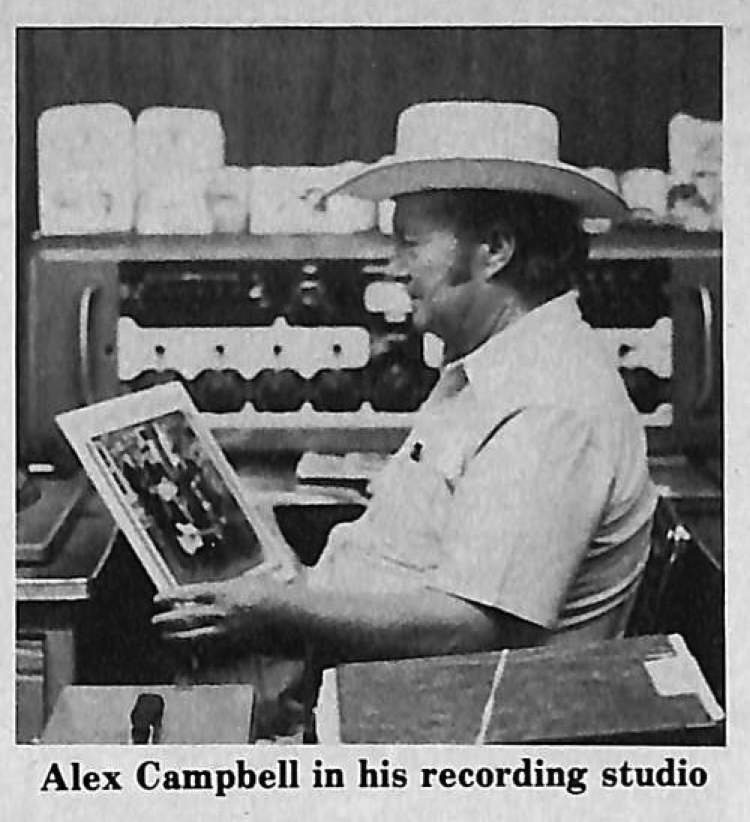

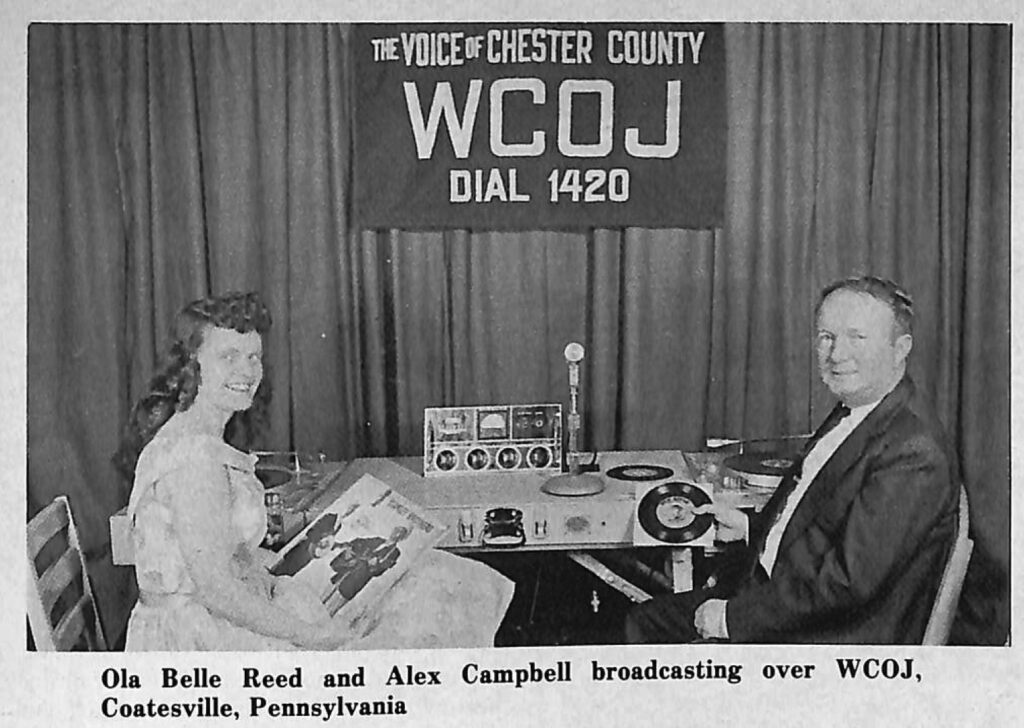

While all this promotion and performing was going on, Ola Belle, Bud, and Alex were also involved in another family enterprise which not only furthered their cause of preserving Southern Appalachian traditions, but also fit well with their music in a highly unusual way. The family’s thriving grocery business, Campbell’s Corner, is a larger, modern version of their father’s grocery store by the same name started in Lansing, North Carolina in 1918. It’s a Southern-style grocery and general store stocked with hard to find “down-home” food and merchandise, with a large musical instrument and record department in the back. But the most unique part of the store is an actual broadcasting studio where Alex has operated a remote radio show of live and recorded bluegrass and country music since the sixties on local stations and stations as far away as WWVA. By operating as an “independent DJ” from his own store, he promotes the grocery and record business and at the same time can play his kind of music, doing his part in making sure authentic Southern and traditional country music is not forgotten while modern automated radio stations ignore it.

Campbell’s Corner, the successful concert business, and the performing and recording of traditional music as a band, are all examples of how Ola Belle and Bud have managed to fuse together their music and their lifestyle with business, without destroying the message and the traditions of their music in the process.

Ola Belle believes that music is an important vehicle in carrying values and morals from one generation to the next, but in getting the music out to the people you have to be careful not to get carried away and become commercial: “I know you have to sell records. I know you have to stay in business. I don’t call that commercial. You have to make a living. What I’m trying to say is—one of the big stars we put on the stage, I told him, ‘One of your ardent fans is out here, an old grayheaded lady, and she wants you to sing her this old hillbilly song.’ ” Ola Belle puts her nose up in the air and makes a face, imitating the man’s snobbish reply: “ ‘Never heard of it.’”

It is important to Ola Belle that you do not change yourself or your music in an attempt to become more popular or accepted. She tells the story of how the “Western” part of “Country and Western” was dropped at the time the Grand Ole Opry was becoming the most listened to radio show in the country: “They had to change it because the straight country title was more accepted, representing American popular music and some of the stars coming in were more modern. They didn’t eliminate the hillbilly music and country and western titles because they were ashamed of it; they figured they were doing something progressive, to help the music. One of these artists later told me ‘We thought we had made a good change. But evidently it was the saddest thing we ever done.’ Now I’m not against good country music, pretty singing and pretty songs —it’s the words and how it comes out from the person that’s doing it —I don’t know how to explain it, but when we sing and play, we enjoy it and feel it. But that artist told me, they made a bad mistake. Because it’s commercialism that does it, in any field. But see, they changed in the name of progress. And as soon as the Urban Cowboy clothes came back, some of them wanted to put the ‘Western’ back.

“I think a lot of people today listen to the top notch stars and listen to their music and know who they are but seldom hear some of the words that come in there. They idolize the artist.” She tells about playing at a fireman’s carnival where they were billed with the Andrews Sisters, when someone asked her how she felt playing with such a famous group. She didn’t understand what they meant because she didn’t know who the Andrews Sisters were, other than just another good singing group. “I’ve always liked to play and didn’t even have sense enough to know the Andrews Sisters were nationally known.”

But it is not just idolizing artists and not hearing the music that Ola Belle objects to when commercialism sets in, it’s an unnatural change in the music. It is here that the Reeds have achieved a fine balance between natural change in music that evolves and grown to new forms while keeping the old form intact, and unnatural change forced on the music in an effort to make it more appealing. “I’m not against progress if it’s headed in any direction and I know there’s going to be changes. I’m not prejudiced against any kind of music. I’m only prejudiced against prejudice.”

As an example of how one can preserve traditional music and at the same time stay open to change and not become prejudiced Ola Belle tells the story of their patient attitude with their sons, Eric and David, who played the music of their generation before they could learn their parents’ music and synthesize the two. Today, Eric is a preacher and David performs with his parents as well as playing gospel music in churches, prisons, and senior citizens’ homes. His music has added a little of the rock music beat and drive to Ola Belle’s traditional music without hurting or destroying it. “Electric guitars, drums, electric bass, wah-wah pedals and strobe lights up in the bedroom! Everybody said ‘How do you stand that noise? Why do you let them?’ Every kid in the country would come. You could hear them a mile away. And I said, ‘What noise?’ And David said one time, ‘Momma you don’t care if I play this kind of music?’ And I said, ‘No.’ And I never said a word. We were patient. It didn’t bother us because at least our children were home and doing something when other kids were out. But then he started—I don’t know how he got started—picking with me, him and Eric, playing the bass. It was natural. He started playing with me and Dad. Mandolin, banjo, guitar, bass. Any instrument that come along, it didn’t take him no time to learn to play it, and he put a beat to it.

“Different songs relate to different people in a different fashion, but nearly all the young kids across this country, the young kids in the colleges and in the festivals, the schools, you have to relate to them. It’s the power of projection. How you get your message across to your audience is your whole thing. When you go on the stage, you get a feeling for your people. The power of projection means to be able to communicate with your audience, whoever that is. We all need each other whether we know it or not. And music is a way to relate to one another.

To Ola Belle Reed, playing music has a larger purpose than simply being the best musicians and playing good music. Music must have a message. This attitude seems to be what keeps her happy and satisfied with her work, and contributes to her ability to balance preserving traditional music with staying open to new music and changes. If the music expresses the message for her and feels natural, then it’s right, no matter what kind of music it is.

Bluegrass fans probably know Ola Belle best as a songwriter. Her songs translate beautifully to bluegrass instrumentation and bluegrass vocal harmony because they are full of the lonesome longing for people to love and take care of each other and the tension between the necessity of breaking from your past to move ahead and at the same time trying to keep your past, a feeling that is strong in bluegrass music. Probably the most popular of her songs is “High on a Mountain.” Del McCoury and Hot Rize, as well as some lesser known bluegrass groups have recorded it.

She wrote the song when she went back home to visit her grandmother and her description of the experience sums up exactly what Ola Belle is trying to communicate through her music: “My granddaddy used to own a lot of that land and my mother’s people were from there. We were going around that road, and over to the graveyard where some of our people were buried and there were places where we could stop and look down. So we stopped and I got out and looked w-a-a-a-y down, and I could almost see the New River and the land down there where we lived. And I was just a-thinking. I wrote it about people. Do they remember one another? In other words, all of the people we knew, in their homes and everything, the ones that’s left, the real old ones. When you’re away from people so long, it was just as though you were looking back and wondering if the ones that’s left could even remember. Lots of time you go to see the old people and they have to look at you three or four times before they remember you. It wasn’t a love song. It was just a sort of like history about people. I look down through there and I could almost see, but I couldn’t see it, where our house was, and the people we knew, the older people. It wasn’t that I was thinking about forgetting. You don’t forget your background. You shouldn’t. I was always proud of my background and the people I knew.”

Ola Belle Reed has never forgotten her background, although she moved on, taking her roots with her to touch other worlds and other lives while enriching her own. She could have been a star; she once turned down a job to play with Oswald when Rachel got married, along with many other job offers from Roy Acuff and even a part in a movie. But she chose to stay in the little rural town of Rising Sun, Maryland where her family was, taking in homeless children and feeding them love and music while doing as much as she could to promote the music with Bud and her brother Alex. Ernest Tubb has told her many times, in letter and in person, “Be yourself, Ola Belle. Don’t change.” By being herself and staying true to her past, but being open and welcoming the many people who have come through her life, young and old, bringing different kinds of music and beliefs, she has managed to create her own music and reach others with her message.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Yes I remember both ola belle and her brother Alex Campbell,at sunset park back in the 1960 and 1970’s