Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – October 2025

Notes & Queries – October 2025

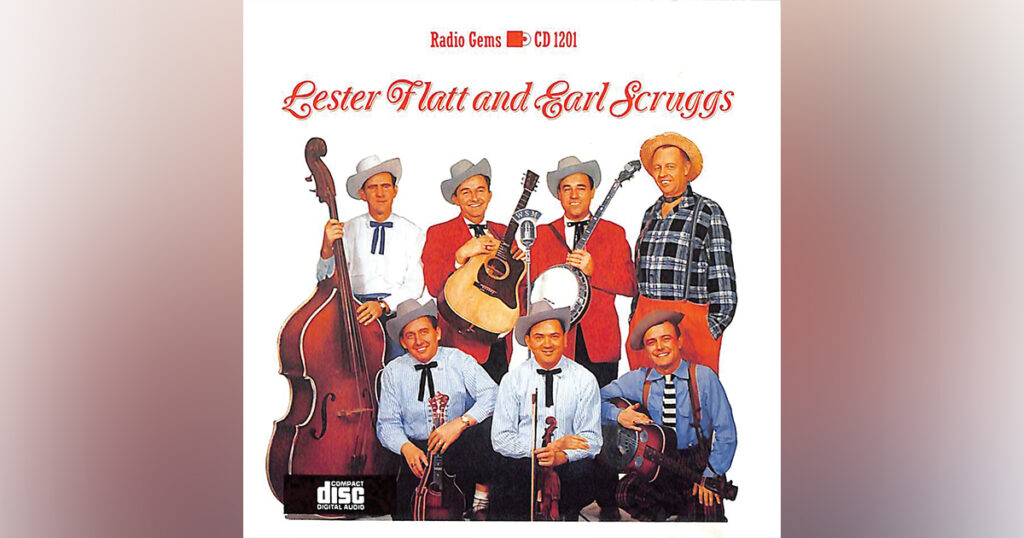

Q: I just found that Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs actually recorded “The Family Who Prays Never Shall Part.” I know this is an old Louvin Brothers song, but do you know by chance when Flatt and Scruggs recorded it? Wayne Hoffman, via email.

A: The song was never commercially recorded by Flatt & Scruggs, but it did appear on a 1991 CD that was released on the Radio Gems label. The brief notes that came with the disc stated that “besides cutting commercial recordings for Mercury and Columbia records and doing radio shows for a variety of radio stations throughout the Southeast, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs also recorded a string of 12” and 16” radio transcriptions for various sponsors. All the songs you hear on this compilation were taken from 16” radio transcriptions and were all recorded in the period between 1954 and 1957.” And, speaking specifically about the song in question, “the greatest surprise to collectors of Bluegrass music is the recording of THE FAMILY WHO PRAYS. This song, originally written and recorded by the Louvin Brothers at their first session for Capitol Records in 1952, features a great trio by Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and Curly Seckler in addition to strong lead guitar work by Earl Scruggs. According to the transcription label, this song was recorded in 1954.”

Actually, it appears that there are two groups of songs on the CD, one set from 1954 and another from 1957. Songs from 1954 are all of a gospel nature and include “The Family Who Prays,” “Get in Line Brother,” “Preachin’ Prayin’ Singin’“ and “Who Will Sing for Me.” Songs and tunes from 1957 include “Have You Come to Say Goodbye,” “Give Me the Flowers While I’m Living,” “A Hundred Years From Now,” “Brother, I’m Getting Ready to Go,” “On My Mind,” “Earl’s Breakdown,” and “Stonewall.”

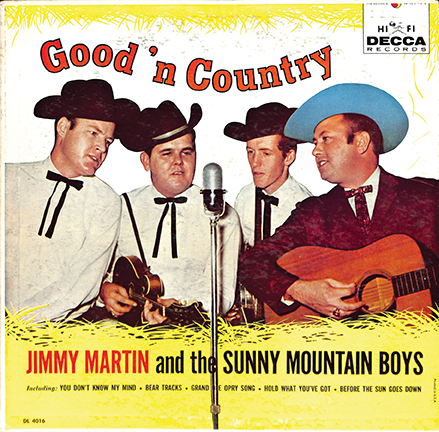

Q: On the Jimmy Martin album Good ‘n Country (Decca DL 4016), four musicians are featured in the jacket’s cover photo. I recognize three of them: mandolin player Paul Williams, banjoist J. D. Crowe, and guitarist/band leader Jimmy Martin. My question is, who is the fourth person standing at the far left in the photo? Billy Q. Smith, via email.

A: Unfortunately, the mystery person’s name is most likely lost to the ages. What is interesting, though, is that he was not a member of Jimmy Martin’s band. On my behalf, longtime friend Dan Moneyhun reached out to Paul Williams about the unidentified person in the photo. Williams related that “the guy in the picture wasn’t even in the band. He was just there for the photo shoot.” Williams added that he thought the stand-in’s first name was Troy, but couldn’t remember his last name. It’s possible he was an assistant to Owen Bradley, or even a member of the popular Owen Bradley Orchestra – but that is just speculation.

The Good ‘n Country album was Jimmy Martin’s first long-play album. Like a number of bluegrass albums from the late 1950s and early ‘60s, it was a collection of songs and tunes that had been recorded earlier – in this case, over a four-year period from 1956 to 1960 – and were released previously as singles.

The earliest song in Jimmy Martin’s collection, “Before the Sun Goes Down,” was recorded during his very first session for Decca Records on May 9, 1956. This session, and all of the others featured on this album, took place at Bradley Studios, located at 804 16th Avenue South in Nashville. The lineup of musicians included mandolin player and tenor singer Earl Taylor, fiddle player Tommy Vaden, and bass player Howard Watts.

Later that year, on December 1, 1956, Martin returned to Bradley Studios to record “The Grand Ole Opry Song.” This version, which was later re-recorded for the multi-million-selling Will the Circle Be Unbroken album in the early 1970s, featured a slightly altered lineup. Earl Taylor continued on mandolin and tenor vocals while Howard Watts played bass. New additions to the group included J.D. Crowe on banjo and Gordon Terry on fiddle, marking a shift in the band’s dynamic.

Fast forward to February 19, 1958, when Martin recorded the gospel song “I Like to Hear ‘Em Preach It.” This session showcased one of his all-star lineups for the Sunny Mountain Boys, including J.D. Crowe on banjo and baritone vocals, Paul Williams on mandolin and tenor vocals, Gordon Terry on fiddle, and Floyd “Lightning” Chance on bass.

On November 20, 1958, Martin recorded five songs, including “Night,” “It’s Not Like Home,” “Hold What You Got,” and two instrumentals, “Bear Tracks” and “Cripple Creek.” This session featured a similar lineup to the previous one, with the exception of Chubby Wise replacing Gordon Terry on fiddle.

The final session for the album took place on January 14, 1960, and included four songs: “Who’ll Sing for Me” (a gospel track), “All the Good Times Are Past and Gone,” “You Don’t Know My Mind,” and “Homesick.” Country Johnny Mathis joined as a guest, singing bass on “Who’ll Sing for Me.” The session also featured Paul Williams on mandolin and tenor vocals, J.D. Crowe on baritone and banjo, Roy Husky Jr. on bass, and Benny Martin on fiddle.

In naming the album, Paul Williams remembered that “Owen Bradley was producing the record and asked Jimmy what did he want to title the album? Jimmy said he didn’t know.” Williams offered, “‘What about Good ‘n Country?’ Owen said it sounded good to him. ‘What about you, Jimmy?’ ‘Sounds good to me,’ he said. That’s how the title came about.”

The May 9, 1960, issue of Billboard magazine gave the release a hearty review: “Here’s a good down-to-earth collection of tunes with the bluegrass sound. Martin and his boys have the real thing in terms of the nasal vocal feeling plus guitar, ukulele, mandolin, and five-stringed banjo. Martin shows the strong influence of Bill Monroe, with whom he spent several years. There’s much happy, bouncy, hoedown styled listening here, plus a bit of religion. Recommended for the traditional fans.”

Over Jordan

Benny Howard Birchfield (June 6, 1937 – August 2, 2025) was a multi-instrumentalist from Isaban, West Virginia, a tiny hamlet that lies near the convergence of Virginia, Kentucky, and West Virginia. He is best known for his outstanding vocal work for the Osborne Brothers. He was proficient on guitar, banjo, and bass. Among his first professional work was a 1957 recording session for an up-and-coming country music group headed by Nickie Green and called the Cumberland Mountain Boys. Most of the members were Tennessee natives. Birchfield played banjo and contributed the original instrumental “Hamblen County Breakdown.”

In the fall of 1959, Birchfield joined the Osborne Brothers, playing bass and occasional twin banjos with Sonny Osborne. Though not yet recording with the group, Birchfield did have the opportunity to perform at what is generally regarded as the first bluegrass college concert. Antioch College students Jeremy and Alice (Gerrard) Foster engaged the Osborne Brothers for a concert at the school on March 5, 1960.

It wasn’t until 1962 that Birchfield got to record with the Osbornes. An album for the MGM label that was released at the end of the year, called Bluegrass Instrumentals, found Birchfield playing twin banjos. It was about the same time that his position changed within the band, from an instrumentalist to a rhythm guitarist and lead singer; he was a third part of the Osborne Brothers’ unique vocal trios. Over four days in January 1963, the group recorded the album Cuttin’ Grass (MGM 4149).

Birchfield’s collaboration with Osborne Brothers continued with the group’s move to Decca Records. At sessions in mid-1963 and again in 1964, material was recorded for their Decca debut album Voices in Bluegrass (Decca 4702). He even shared composer and arranger credits on several songs.

The third week in July 1964 found the Osborne Brothers on tour in the northeast, which included one day at the Newport Folk Festival. They appeared on a Saturday 10:00 a. m. Country Music workshop that also featured the Stanley Brothers. Photos by Dave Gahr showed Birchfield on stage with the Stanley Brothers. Birchfield explained: “When I worked with the Osborne Brothers, we didn’t have a bass player for about the first three years. So, I would play guitar so hard to try and fill the void of not having a bass player. George Shuffler and I had been friends for a thousand years, and we agreed to play bass with each other’s band [at the workshop] since neither of them had a bass player.”

Birchfield departed the Osborne Brothers sometime after the Newport festival. His next recorded work was with the duo of Landon Messer and Albert Parsley. With them, he recorded eight songs for the Lexington, Kentucky-based REM label:

Rem 45 353 Hemlock and Primroses / Barbara Allen

Rem 45 363 Hem of His Garment / Walking the Path to Heaven

Rem 45 374 When / Nothing But the Blues

Rem 45 414 Walking By Faith / The Nail Scarred Hands

The mid-1960s found Birchfield in Cincinnati, where he frequently worked at the Ken-Mill club. A rotating cast of pickers and singers included Paul Mullins, Walter Hensley, Jim McCall, Earl Taylor, “Boatwhistle” and Junior McIntyre, and Harley Gabbard.

The REM label continued to be an outlet for Birchfield’s recorded output. In 1965, Paul Mullins and Bennie [sic] Birchfield were listed as co-leaders of the Backwoods Boys Quartet. They had one single released on the label: REM 45 371 “We Shall Meet Some Day” / “Nearer My God to Thee.” Mullins and Birchfield shared arranger credits on “We Shall Meet Some Day.”

Yet another ca. 1965 REM release was credited to Jim McCall and Benny Birchfield. REM 45 380 featured two songs that were both credited to dobro player Harley Gabbard: “Divorced But Not Free” / “Uncle Bill’s Still.” The duo of Jim McCall and Benny Birchfield with the Bluegrass Partners continued to play together through at least the summer of 1966; they appeared at Ohio’s Chautauqua Park in August 1966.

While still part of the Cincinnati music community, Birchfield sat in on bass on a session by Charlie Moore and Bill Napier that was cut for King Records. Twelve songs were released in late summer 1966 on an album called Country Music Goes to Viet Nam (King KLP 982).

Birchfield returned to the Osborne Brothers for a six-month stretch that ran from September 1966 to March 1967. While with them, he assisted with the recording of another album for the Decca label: Modern Sounds of Bluegrass (DL 4903).

Birchfield’s bluegrass activities came to a close, for the most part, with his marriage to country music singer Jean Shepard on November 21, 1968. In 1970, Birchfield was instrumental in helping to revitalize Shepard’s career. They formed a backing group known as The Second Fiddles, of which Birchfield was the band leader. The band name was a reference to a 1964 hit by Shepard called “Second Fiddle (To an Old Guitar).” He produced and played on several of Shepard’s recordings from the mid- and late 1970s. He even formed a label, Birchfield, for the release of several of the projects. Throughout the mid-1970s, the group averaged 125,000 miles of travel per year.

Birchfield maintained a friendship and working relationship with the Osborne Brothers. A 1978 advertisement by the duo’s Allied Entertainers booking agency listed Birchfield as an available solo artist. He also appeared on two late 1970s albums by the Osbornes. One was a double-album set that also featured Mac Wiseman called The Essential Bluegrass Album (CMH 9016). The other was Bluegrass Concerto (CMH 6231).

In the late 1980s, Birchfield served as a bus driver/road manager/guitarist for singer Roy Orbison. Tragically, Orbison died of a heart attack (December 6, 1988) while visiting at the home of Jean Shepard and Benny Birchfield.

In recent years, Birchfield maintained a presence in the Nashville music community and served as a mentor to younger musicians.

Joseph Charles “Joe” Hickerson (October 20, 1935 – August 17, 2025) was a towering figure in the world of folk music. In a professional life that spanned over six decades, he was renowned for his work as a folklorist, an ethnomusicologist, an archivist, and as a performer. His work not only preserved the rich traditions of folk music but also bridged the gap between traditional and contemporary audiences. While his legacy is deeply rooted in folk music, his contributions to bluegrass and its preservation are equally noteworthy.

Early Life and Introduction to Folk Music

Born in Illinois and raised in Connecticut, Joe Hickerson’s love for music began in his childhood. He learned to sing and play the guitar early on, but it was during his time at Oberlin College in the 1950s that his passion for folk music truly blossomed. As a physics major, he became deeply involved in the college’s folk scene, founding the Oberlin Folk Song Club and organizing the first Oberlin Folk Festival in 1957. That same year, he joined The Folksmiths, an eight-piece folk group that toured summer camps, introducing audiences to the joys of folk music. Their 1958 album, We’ve Got Some Singing to Do, included the first folk revival recording of “Kumbaya,” a song that would become iconic in the folk canon.

Academic Pursuits and Early Career

After graduating from Oberlin, Hickerson pursued graduate studies in folklore, ethnomusicology, and anthropology at Indiana University; he earned a master’s degree in folklore. During this time, he organized the Indiana University Folk Song club, began performing as a solo artist, hosting radio shows, and honing his skills as a folklore archivist.

In 1963, Hickerson joined the Library of Congress as a reference librarian in the Archive of Folk Song, which later became the American Folklife Center (AFC). Over the next 35 years, he would rise to become the head of the archive, a position he held until his retirement in 1998. His tenure at the Library of Congress was marked by meticulous scholarship, passionate advocacy for folk traditions, and a commitment to making the archive accessible to the public.

Contributions to Bluegrass Music

While Hickerson’s primary focus was on folk music, his work intersected with bluegrass in significant ways. As an archivist, he played a crucial role in preserving and documenting bluegrass recordings, ensuring that the genre’s rich history was not lost to time. His expertise was sought after by musicians, researchers, and filmmakers alike. For instance, he served as a research consultant for the films O Brother, Where Art Thou? and Cold Mountain, both of which prominently featured bluegrass and old-time music.

On numerous occasions, Hickerson’s deep knowledge of traditional songs made him a reliable source for answers to questions posted by various “Notes & Queries” readers. He was instrumental in tracing the origins of songs that became staples of the bluegrass repertoire. For example, his research on “Black Jack Davy” and “The Cuckoo Bird” provided valuable insights into their historical roots and connections to other folk traditions.

In addition to his archival work, Hickerson contributed to the bluegrass community through his writings. He authored scholarly articles, reviews, and bibliographies in folklore and ethnomusicology publications, shedding light on the interconnectedness of folk and bluegrass traditions. His “Song Finder” column in Sing Out! magazine became a beloved resource for those seeking information about traditional songs, including many that found their way into the bluegrass repertoire.

A Lifelong Performer and Advocate

Hickerson’s contributions to music extended beyond academia and archiving. As a performer, he brought traditional songs to life, captivating audiences with his warm voice and skilled guitar playing. His repertoire included labor songs, children’s songs, parodies, Irish-American ballads, sea shanties, and, of course, bluegrass-inspired tunes. Over the course of his career, he performed more than a thousand times across the United States, Canada, Finland, and Ukraine, as well as on the popular radio show A Prairie Home Companion.

One of Hickerson’s most enduring contributions to music was his role in co-authoring the iconic song “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” with Pete Seeger. While not a bluegrass song in the traditional sense, its themes of loss and longing resonated deeply with audiences across genres, including bluegrass. Hickerson’s addition of two verses to Seeger’s original composition transformed it into a six-verse masterpiece that became a global anthem for peace.

Legacy and Impact

Joe Hickerson’s impact on the world of folk and bluegrass music cannot be overstated. As an archivist, he preserved countless recordings and documents, ensuring that future generations would have access to the rich tapestry of American musical traditions. As a performer, he brought these traditions to life, inspiring audiences with his passion and authenticity. And as a scholar, he deepened our understanding of the cultural and historical contexts that shaped these songs.

Hickerson’s work at the Library of Congress was particularly transformative. Under his leadership, the Archive of Folk Song expanded its collections and became a vital resource for musicians, researchers, and educators. His efforts to document and preserve bluegrass recordings helped to elevate the genre’s status and ensure its place in the broader narrative of American music.

In retirement, Hickerson continued to perform, lecture, and write, sharing his knowledge and love for folk music with new audiences. His humor, humility, and boundless curiosity endeared him to all who knew him. As Pete Seeger once said, Hickerson was a “great song leader,” a title that speaks to his ability to bring people together through music.