Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – October 2023

Notes & Queries – October 2023

Queries

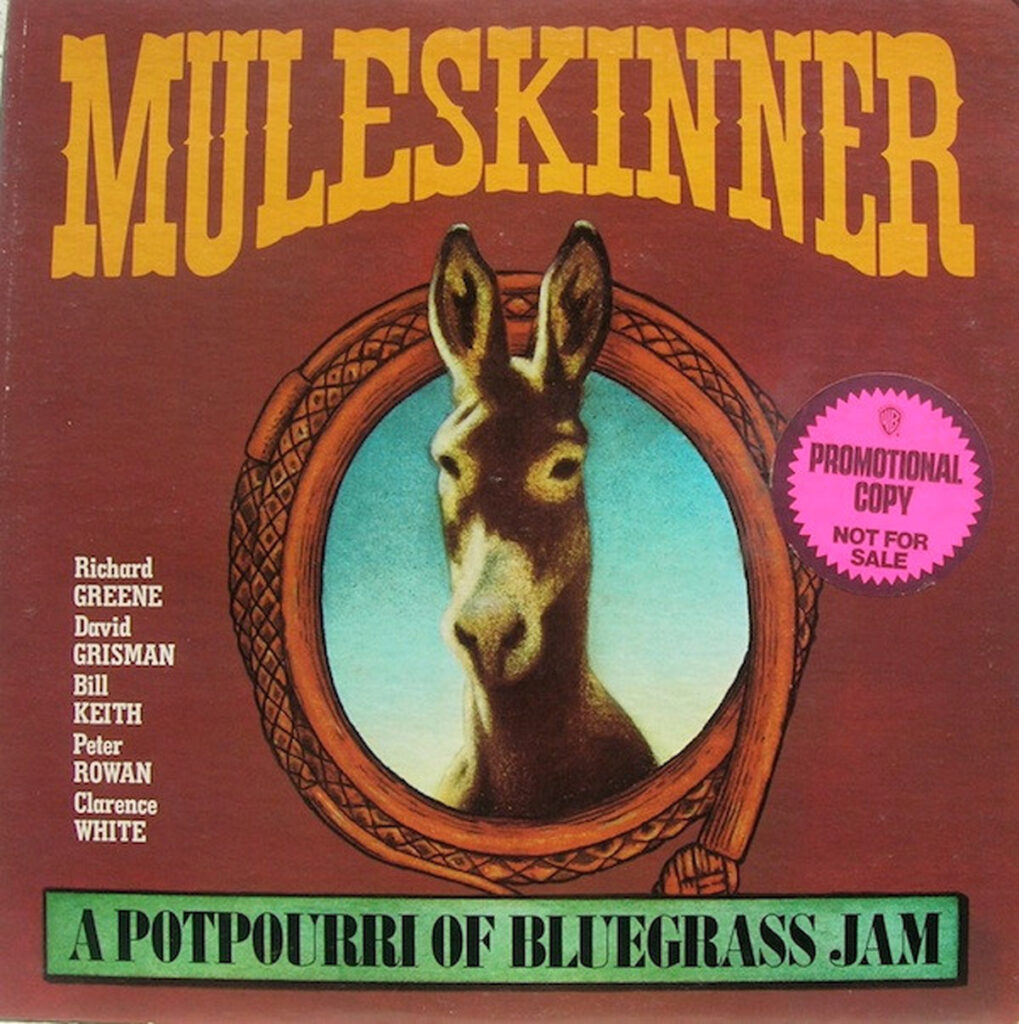

Q: I was reading John Hartley Fox’s article ‘Muleskinner & Clarence White’ in the June 2023 Bluegrass Unlimited and noticed what I think are (slight) errors. I grew up in LA and had been to the Ash Grove many times to see the likes of The Kentucky Colonels and Bill Monroe with Billy Keith in his band. Fox talks of the ‘Muleskinner’ all-star band coming together in early 1973 for a TV show, and afterwards appearing at the Ash Grove. I was in school at UC San Diego at the time, and caught wind of the ‘Bluegrass Dropouts’ coming together for a gig at the Ash Grove. Being a banjo player recognizing the innovations and musicianship Keith brought to that instrument, I came up for that show. We knew him as Billy Keith, presumably because Bill Monroe didn’t allow other Bills in his band, but evidently Billy was ok, i.e. the fiddler Billy Baker. Peter Rowan, Richard Greene, David Grisman, and, especially, Clarence White were also very strong draws.

Claims that Bill Keith was *not* at the Ash Grove gig seem refuted by the Richard Cromelin review of that gig in the LA Times. I ‘remember’ Keith at that gig, because if it were someone else, I would remember that! I recall Clarence White and his trick electric guitar, which he could bend one note by pulling down on the strap. Later named the ‘B bender’. On the ‘Potpourri’ recording, he makes it sound like a pedal steel. My other distinct memory of this gig was the excellent rhythm mandolin playing of David Grisman. He was good and interesting. In bluegrass, the mandolin takes the place of drums in a sense.

I’m pretty sure they *didn’t* have actual drums at their Ash Grove appearance! William Forrest, via e-mail.

A: For a reply, we reached out to the author of the “Muleskinner” article, Jon Hartley Fox: “Thanks very much to William Forrest for setting the record straight. I had heard (or read) somewhere that Keith wasn’t at the Ash Grove gigs, but he clearly was, as your eyewitness account and the clipping attest. I envy Mr. Forrest for being at the Ash Grove that night. I wish I could have been there. And no, there wasn’t a drummer at those shows. As for ‘Billy’ Keith, I’ve always heard that during his time in Monroe’s band, Keith was known as ‘Brad’ (from his middle name Bradford), as there could be only one Bill in that band.”

Q: Any chance you know who the fiddler is on the Rebel single by Al Jones and Frank Necessary called “Spruce Mountain Fiddle”? Jon Wilson, Two Rock, CA

A: The single “Dreamin’ and Grievin’“ / “Spruce Mountain Fiddle” by Al Jones, Frank Necessary and the Spruce Mountain Boys (Rebel single F-260) was released around March 1966. Salem, Virginia, bluegrass aficionado Jerry Steinberg interviewed Al Jones some years ago and asked specifically about this recording. According to Al Jones, the personnel consisted of himself on guitar, Frank Necessary on banjo, Mac McGinnis on fiddle, and Lawrence “Pee Wee” Faudree on dobro. He was unsure about the bass player but a likely candidate was Frank Goolsby.

While Al Jones and Frank Necessary have names that are somewhat recognizable within the bluegrass community, those belonging to Mac McGinnis, Pee Wee Faudree, and Frank Goolsby are not so well-known. Fiddler Jack Buren “Mac” McGinnis (September 25, 1930 – December 22, 1974) was a North Carolina native, hailing from a community known as Roaring Creek in Avery County. By 1950, he had relocated to the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D. C. A photograph from the early 1950s showed Mac with fiddle in hand, along with his guitar playing wife, Minnie. A construction worker by trade, Mac was most active with his music throughout the 1960s and early ‘70s. It was around 1962 that Mac met Frank Necessary, who subsequently played with him for the next five years. In the early part of 1968, Mac played with Patsy Stoneman in a group that also included Charlie Waller and Ed Ferris. Later that year, he also fronted his own band. In 1969, he teamed up with Al Jones to co-lead the Spruce Mountain Boys. McGinnis’ last work was in the early 1970s as the leader of a band called the Fields of Blue Grass (and was sometimes billed as Friends of New Grass). His career was tragically cut short when he was involved in a head-on collision on December 22, 1974, he was 44. A benefit concert that included Al Jones and Frank Necessary, among others, drew 1,500 attendees. It is likely that McGinnis’ only recorded work was the Rebel 45 rpm disc that included his composition “Spruce Mountain Fiddle.”

Dobro player Lawrence James “Pee Wee” Faudree (April 16, 1925 – April 6, 1988) was a native of Richmond, Virginia, who spent his formative years in Annapolis and nearby Arnold, Maryland. Like many of his generation, he was a World War II veteran. Attaining the rank of private first class, his war-time service included duty as a military policeman. He was well-decorated and was awarded the Purple Heart, the American Theatre Ribbon, the Philippine Liberation Ribbon with one Bronze Star, the Bronze Star, the Combat Infantry Badge, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Ribbon with three Bronze Stars, the Good Conduct Medal and the World War II Victory Medal. After the war, he worked as an inspector for the Department of Transportation. Musically, some of his first known work was around 1960 in a group that was headed by banjoist Johnny Whisnant. The middle and late 1960s found him in various incarnations of the Spruce Mountain Boys. Towards the end of 1967, he played in a short-lived group called the Chesapeake Playboys. Faudree’s last-known work was in 1969 with Mac McGinnis.

Bass player Frank Goolsby remains a mystery as far as when he was born and where he came from. His known work in music followed that of his Spruce Mountain Boys bandmates: performed with Johnnie Whisnant (ca. 1960), the Spruce Mountain Boys (1966-’67), the Chesapeake Playboys (1967), and Mac McGinnis (1969). One bit of work that differed from the others was his playing bass on recordings by dobro player Kenny Haddock that appeared on the Zap label in 1967; Charlie Waller played guitar. The album was somewhat unusual in that the A side was devoted to Haddock while the B side featured fiddle tunes by Billy Baker. The album was titled Dobro and Fiddle. The Haddock sides featuring Goolsby included “Weeping Willow,” “Beautiful Dreamer,” “Maggie,” “Jubilee March,” and “Mountain Dew.”

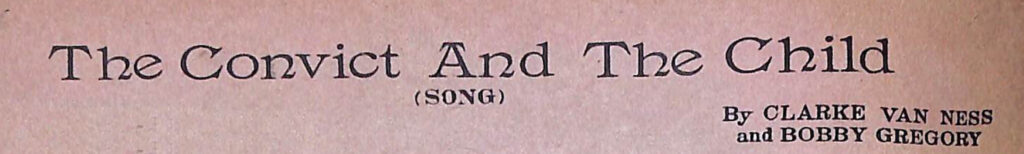

Q: Do you know anything about the song “The Convict and The Child”? It is credited to Frank Wakefield on his releases of it but I am skeptical. Billy Q. Smith, via e-mail.

A: Your suspicions are correct. An entry at the Library of Congress, dated January 18, 1939, credits the song (both words and music) to the duo of Clarke Van Ness and Bobby Gregory. A songbook that was issued a short time later, titled Harry Bryan, The Lone Cowboy, contained the words and music to “The Convict and the Child”; the lyrics are identical to those recorded by Frank Wakefield.

The version that was attributed to Frank Wakefield was published by Wynwood Music, which was owned by Bluegrass Unlimited co-founder Pete Kuykendall. Early in his development as a bluegrass musician and recording engineer, Kuykendall made numerous visits to the Library of Congress in search of material that could be performed in a bluegrass style. Given that his Wynwood Music published the song, it seems likely that this was one of the songs he discovered on one of his Library of Congress outings.

Of the song’s original writers, Clarke Van Ness (pseudonym for Cyrus Van Ness Clark, July 4, 1894 – July 6, 1983) was a native of Dansville, New York, a small village located about fifty miles south of Rochester. He developed an interest in music at an early stage in life; he was a member of the Dansville High School Sunflower Minstrels. By 1915 (age 18), he was enrolled at the University of Illinois and teamed up with several of his classmates to compose new songs. Among his early titles were “Where the Boneyard Flows,” “There’s Bugs All Around,” “When it’s Moonlight on the Mississippi Shore,” and “Sailing Down the Old Potomac.” With one of his classmates, he formed Illini Music Publishing and assumed the role of general manager.

Van Ness joined the Army in the waning days of World War I. The same year, 1918, found him married to a Vesta F. Krein. The union faltered ten years later over an alleged infidelity. At the time of the couple’s divorce, Van Ness was working as an insurance broker.

The 1930s saw Van Ness developing as a music professional. In 1932, Rialto Music published Clarke’s Complete Minstrel Show, which also included songs and jokes. In 1944, the same firm published Van Ness Clarke’s Comedy Collection No. 1. By 1939, one source pegged Van Ness as the head of Rialto.

Two of Van Ness’ biggest songs were published in the early 1940s: “Filipino Baby” and “Don’t Let Your Sweet Love Die.” For each, he was listed as a co-writer, which seemed to be the case with most of his work. His gift was with lyrics, while others contributed melodies.

In 1944, Van Ness served as an associate editor for the newly launched Mountain Broadcast and Prairie Recorder magazine. By 1946, he served as the publication’s president.

Starting in the late 1940s, Van Ness’ songs began to be published by Dixie Music, of which he appeared to have some sort of connection as an employee or owner.

Aside from a third-degree assault charge in 1959, Van Ness drifted into obscurity. He died in Rhode Island in 1983.

Co-writer Robert Calvin “Bobby” Gregory (April 24, 1900 – May 12, 1971) was a native of the Shenandoah Valley town of Staunton, Virginia. He logged time as a cowboy, lumberjack, sailor, and circus and rodeo musician. As an entertainer, he shared the stage with a number of western themed performers including Roy Rogers, Hank Snow, Smiley Burnette, The Lone Ranger, and “Big Slim,” the Lone Cowboy. He later fronted his own band, the Cactus Cowboys. He also appeared in twenty western films. As a songwriter, he is reported to have 1,600 songs to his credit.

Over Jordan

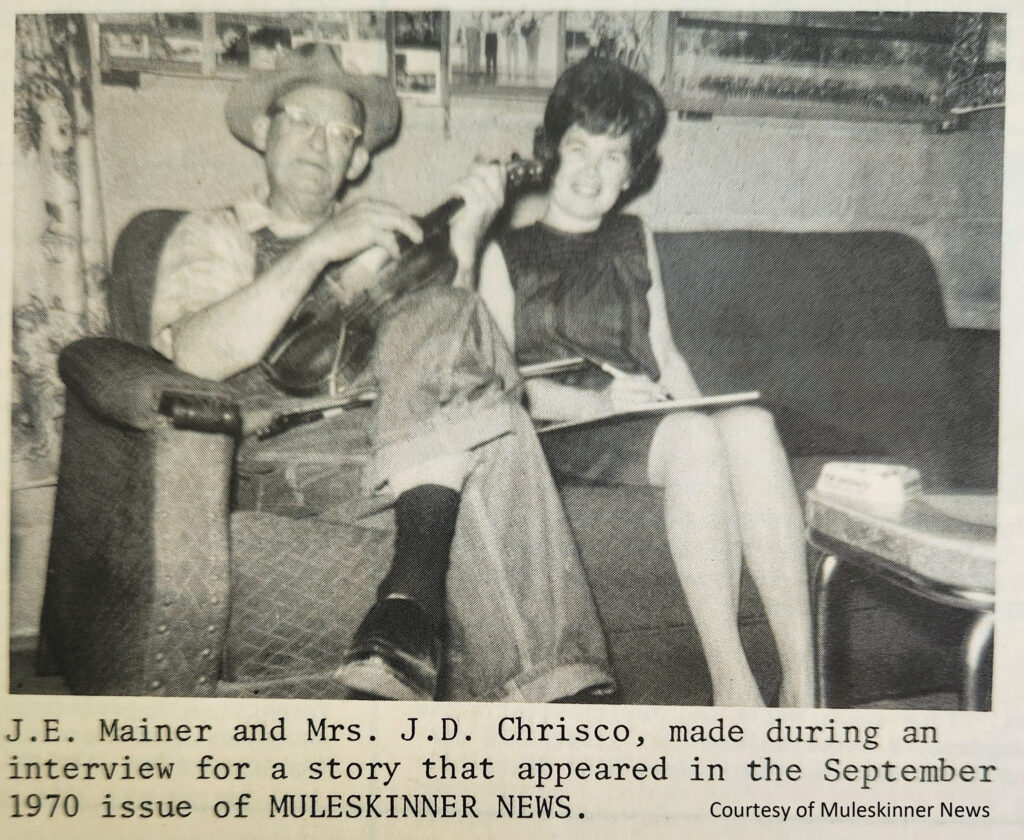

Treva Jane Cox Chrisco (September 25, 1924 — August 11, 2023) was a longtime fan and supporter of bluegrass music in central North Carolina. In a 1971 article in Muleskinner News, author Billy R. Greene cited her as “beyond the shadow of a doubt, one of the greatest fans, promoters and supporters of Blue Grass music to arise from our present generation.”

Mrs. Chrisco’s one-person bluegrass crusade got underway in 1967. She developed a network of outlets for the distribution of flyers for upcoming concerts and also wrote about events in her weekly Randolph Guide newspaper column which ran for over twenty years. As a byproduct of her promotional work, she amassed a large collection of photos, articles, posters and handbills, and, of course, record albums.

In addition to her concert promotion, Mrs. Chrisco contributed articles to a number of bluegrass publications, including early editions of Bluegrass Unlimited, Pickin’, and Muleskinner News. Most, if not all, were about North Carolina musicians or events, including legendary old-time fiddler J. E. Mainer, banjoist/instrument repairman C. E. Ward, one-armed fiddler Frank Hamilton, the Bluegrass Gentlemen, and the Happy Hollow String Band.

In recognition of Mrs. Chrisco’s early promotional work, she received a plaque of appreciation that was presented at the Montgomery County Bluegrass Festival that was held in Troy, North Carolina, in May 1975.

Mrs. Chrisco’s promotion of bluegrass continued for many years. Frequent Bluegrass Unlimited contributor Penny Parsons recalled that “I spoke with her on the phone when I worked at Sugar Hill Records [1980s and ‘90s], and she always wanted to cover anything that seemed relevant to Central North Carolina. Funny, I never knew her first name. She always referred to herself as, and used the byline, ‘Mrs. J.D. Chrisco’.”

In many families, bluegrass is a music that is often passed from one generation to the next. Such is the case with Mrs. Chrisco and current readers of Bluegrass Unlimited are no doubt familiar with the contribution of articles by her banjo-picking daughter, Sandy Hatley.

Paul Prestopino (September 20, 1938 – July 16, 2023, prepared by Richard D. Smith) a renowned multi-instrument sideman and recording engineer, with long experience in bluegrass, old-time, folk and contra dance musics, passed away peacefully at his home in Roosevelt, New Jersey, on July 16, 2023. He was 84.

One of two sons of acclaimed American artist Gregorio Prestopino and his wife Elizabeth (Dauber) Prestopino, Paul became a mainstay of the vibrant 1960s Folk Revival scene in New York City’s Greenwich Village. He played mandolin in the pathbreaking “citybilly” bluegrass band the Greenbriar Boys (between the tenures of Eric Weissberg and Ralph Rinzler). He soon toured and recorded as a backup musician with the nationally-successful folk act the Chad Mitchell Trio, and later toured extensively with the now-legendary group Peter, Paul & Mary.

His studio work included sessions with Pete Seeger, John Denver, Tom Paxton, Graham Parker, Christine Lavin, and Judy Collins.

Paul also brought the sounds of bluegrass banjo, mandolin, and dobro to hit records by such rock stars as Arrowsmith, Rick Derringer, and Alice Cooper.

How? As a veteran technician with The Record Plant studios (notably their remote mobile operation), he helped countless musicians make their best-possible recordings. And he typically had his acoustic instruments at hand. So, when pop musicians or their producers mused about giving a track more of a folk, bluegrass, or old-time sound, Paul was ready to go.

“Presto” (as he was known to his many friends) was musically active to nearly the end of his days, performing and/or recording with such popular New Jersey-based groups as the Roosevelt String Band, Hold The Mustard, the Princeton Country Dancers Pickup Band, and the Magnolia Street String Band. He was also a fixture at annual jam session reunions in New York City’s Washington Square Park. He received a New Jersey Folk Festival Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018.

Paul Prestopino was also famed for his friendliness, hipster humor, and distinctive sartorial style: brightly colored shirts under bib overalls and multi-hued, mismatched socks. In his fashion sense as well as his music, he was one of a kind. He will be greatly missed and fondly remembered. Paul is survived by his wife Sara, daughter Peri, and granddaughter Roisin.

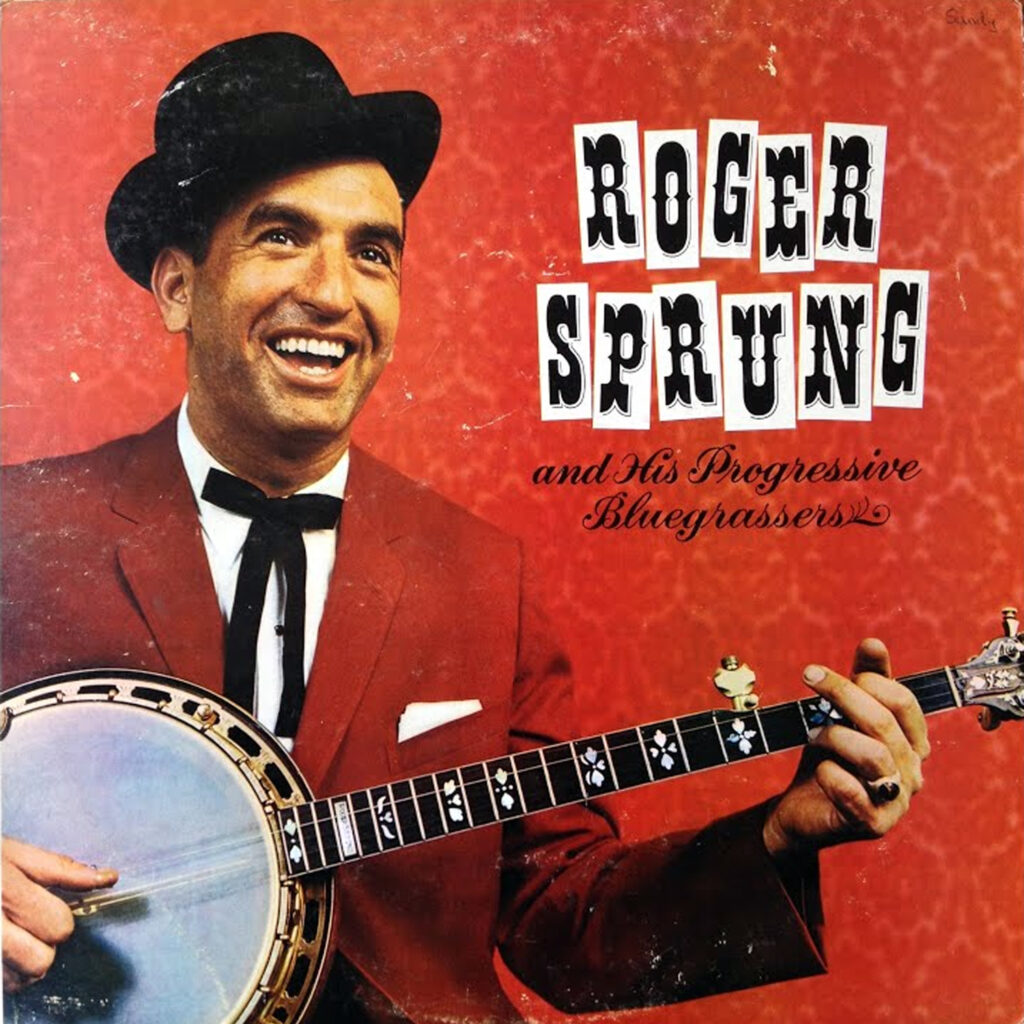

Roger Howard Sprung (August 29, 1930 – July 22, 2023) was tagged in the liner notes to his 1963 album on Folkways as an “instrumentalist, teacher, showman, organizer, collector, tireless popularizer of the new, the different, and the best in folk music.” Most knew him as an inventive banjo stylist whose work with the instrument dated back to the late 1940s. As the first three-finger style banjo player in the New York City area, he did much to introduce bluegrass to that city and to the New England area.

Like many of his generation, Sprung learned to pick by slowing down recordings by Earl Scruggs and figuring out the tunes, note by note. He moved beyond traditional Scruggs style picking and in time adapted many tunes from non-bluegrass sources to the banjo. He also gave lessons to many aspiring pickers. Along the way, he earned the nickname of the Father of Progressive Banjo.

Sprung’s early musical efforts were centered around the piano, which he played in a boogie woogie style. A chance encounter with old-time banjo music in New York’s Washington Square in 1947 completely changed his focus. A year later, he acquired a banjo of his own and within a week’s time, reportedly, learned the basics.

In 1950, Sprung began making annual trips to the southern Appalachians to sell and trade instruments and to learn new songs. He also participated in some of the popular music gatherings such as the Galax Old Time Fiddlers Convention and Union Grove. His associations were generally pleasant but one such event, Asheville’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, resulted in Sprung’s forcible expulsion from the stage; event promoter Bascomb Lamar Lunsford seemingly objected to outside talent being performed at what was basically a local event.

In 1954, Sprung appeared on record for the first time, as part of a folk trio (with Erik Darling and Bob Carey). Their repertoire included songs such as “Round the Bay of Mexico,” “Tom Dooley,” “Midnight Special,” and “Raise a Ruckus.” In 1958, Roger, with Mike Cohen (brother of New Lost City Rambler John Cohen) and Lionel Kilberg, released a self-titled album, The Shanty Boys, on the Elektra label.

By the early 1960s, Sprung had taught 5-string banjo to literally hundreds of students. Among some of the name-recognizable ones are Erik Darling (the Weavers and the Rooftop Singers), Chad Mitchell (of the Chad Mitchell Trio), John Stewart (of the Kingston Trio), and singer-songwriter Harry Chapin. He also maintained a high profile with appearances at Carnegie Hall and on the Dean Martin Leukemia Telethon. In 1963, Sprung recorded the first in a series of three Progressive Bluegrass albums for Folkways. Among the supporting musicians was rising folk performer Doc Watson. Later volumes included future bluegrass luminaries Gene Lowinger and Jody Stecher.

In 1967, Sprung formed his own record label, Showcase, for the release of his albums. Over the next fifteen years, he released at least eight albums that included solo outings, duets with his first wife (Joan), and band projects with Hal Wylie and the Progressive Bluegrassers.

In addition to numerous trophies won at various competitions, Sprung was a 2020 inductee to the American Banjo Museum Hall of Fame.