Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – November 2024

Notes & Queries – November 2024

Q – Did the Stanley Brothers, or Ralph Stanley for that matter, ever record with a Dobro? I’ve got just about everything the Stanley Brothers recorded, including the Rich-R-Tone stuff, the Columbia, Mercury, and King recordings. I don’t remember them recording with a Dobro. Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs pre-mid ‘50s, and Reno & Smiley didn’t record with a Dobro. In country music, there was Brother Oswald with Roy Acuff and people such as Speedy Krise, for example, but they played the old two-finger type Dobro. I felt as though Buck Graves, after Earl taught him the three-finger roll that he would use for the rest of his career, really brought out the Dobro. – Butch Smith

A – I’ve only found two instances where the Stanley Brothers performed with a Dobro. One was with the Stoneman Family and the other was when future New Grass Revival player Curtis Burch sat in with them.

In the book The Stonemans, Ivan Tribe wrote that “Van [Stoneman] got a little experience [on Dobro] now and then filling in with other local or visiting bands. He recalled one such instance when Ralph and Carter, the Stanley Brothers, came to town with virtually no band. They had used a lead guitar heavily in record sessions at this time, but circumstances forced them to use Van on Dobro instead – an instrument virtually foreign to the generally distinct Stanley sound. Van helped them play out their few show dates in the Washington area, with Carter finding the Dobro rather appealing, but the musically conservative Ralph was reluctant and uneasy.”

In 2022, Curtis Burch related his one and only time to play Dobro with the Stanley Brothers: “I lived on the coast of Brunswick, Georgia, from my birth in 1945 to 1971. In the very early ‘60s we would get the Stanley Brothers TV show on Saturdays out of Jacksonville, Florida. In those years they were living in Live Oak, Florida. We would see them live in our area from time to time but I never formally met them then. In 1964 and ‘65, I started playing with a husband-and-wife bluegrass band (Dean and Marie Bence) that lived in Jacksonville, Florida. They had been friends with the Stanleys for some time and we would open for them occasionally.

“One day we were playing a little festival somewhere in north Florida. After we played our set the Stanley Brothers went on with theirs. After they did four or five songs one of our band members said to me, ‘Curtis, Carter is asking for you to come out on stage with them and bring your Dobro!’ I thought they were joking but it was true. So, I went out on stage with my Dobro and walked up to Carter. I was terrified. He asked me if I knew some such and such song, which I had never heard of. Even though I had several of their records and was familiar with a lot of their music, this was a new one on me. I said, ‘No sir, I don’t.’ I was even more terrified when he said ‘Well, we are going to play it right now!’ I managed to get through it and he thanked me and I left the stage.

“I never really understood why Carter would ask me to come out and play Dobro with them as I figured they didn’t care for the instrument. I don’t think Ralph ever knew that I was the same guy that played with New Grass Revival years later, and he probably just as soon not have known, LOL!”

As far as Ralph Stanley’s music is concerned, folklorist Ralph Rinzler posed the following question in the March 1974 edition of Bluegrass Unlimited: “Did you ever think about getting electric instruments and changing your sound? Did you ever consider it?” Ralph Stanley replied: “No, I never liked electric music; never will. Never would ever discuss a Dobro. I like a Dobro alright, but I never did like a Dobro in this type of music.”

Anti-Dobro comments notwithstanding, Ralph Stanley did appear on several songs that included a Dobro. In 2006, Ralph Stanley sang a duet on Josh Turner’s MCA Nashville release Your Man. The gospel-flavored “Me and God” was track number nine on the disc and it featured Dobro by Steve Hinson. Ivor Trueman, host of the authoritative Clinch Mountain Echo (http://www.clinchmountainecho.co.uk/) website pointed out several other tracks: Ralph Stanley sang harmony with Curly Seckler on the song “Lord, I’m Coming Home.” The track, which included Josh Graves on Dobro, was featured on Seckler’s 60 Years of Bluegrass With My Friends. From the Ralph Stanley-Isaacs Family recording A Gospel Gathering, Mike Auldridge played Dobro on two songs on which Stanley sang: “Have You Someone (In Heaven Awaiting)” and “Restore Thy Brother.” An all-star version of “Christmas Time’s a-Coming,” which featured the cast of In the Heat of the Night and friends, contains a snippet of Ralph Stanley’s vocals with Dobro undertones by Josh Graves. Lastly, two projects assembled by Nathan Stanley featured his Papaw with Dobro player Tony Dingus. It appears that in all of these instances, it was a producer’s decision (as opposed to Ralph’s) to include Stanley and a Dobro together.

Q – I listened recently to several albums by Curly Seckler and have questions about two songs. Who wrote “What a Change a Day Can Make” and “Worries on My Mind”? I suspect both were hillbilly songs originally, but that’s just a guess. Good songs in my opinion. Jerry Steinberg

A – The first song, “What a Change One Day Can Make,” is credited to Henry Woodfin Grady Cole (August 26, 1909 – August 31, 1981), a Georgia musician who, with his wife Hazel, was active as a performer from the 1930s to the early 1950s. Grady was also a prolific songwriter and today 158 of his songs are registered with Broadcast Music Incorporated (BMI). There are reports that he wrote as many as 500 songs, most of which apparently went unpublished.

“What A Change One Day Can Make” dates back to 1940 when it was recorded at Grady and Hazel’s second (and final) session for Bluebird Records. It was one of six songs recorded at the session and it was paired with “Forbidden Love” as the duo’s final 78 rpm release for the label. That same year, Grady assembled and released a songbook called Songs of the Mountains and Plains, Book No. 7 and included “What a Change.”

Aside from these two uses (the record and the songbook), “What a Change” pretty much laid dormant until 1960 when the Louvin Brothers recorded it for inclusion in one of their albums for Capitol. Charlie Louvin recalled learning the song from hearing radio broadcasts by Grady and Hazel when they aired over WROM in Rome, Georgia. In notes to the Bear Family boxed set of Louvin Brothers material, Close Harmony, Charlie told interviewer Charles Wolfe that “we heard Grady and admired his work and that song was a part of our family for about as long as I can remember. I guess the way things were changing right about then (in the late 1950s) reminded us to record that song.”

It was another 14 years before anyone else picked up the song. That’s when the Bailey Brothers, having been recently “re-discovered” by Rounder Records, included it on their 1974 album Take Me Back to Happy Valley. In his notes to the album, Joe Wilson wrote that the Bailey Brothers “were given the words by Grady when they were playing at WROM Rome, Georgia, in 1947.”

As to Curly Seckler’s recording of “What a Change One Day Can Make,” it was the title of an album he released on Rich-R-Tone Records in 1986. He was backed by members of the Nashville Grass which included Willis Spears, Kenny Ingram, Johnny Warren, Marty Stuart, and J. T. Gray. How the song came to Curly is not known today. It is worth noting that Curly joined Charlie Monroe’s group in mid-1945. One of the outfit’s first radio assignments was at WBT in Charlotte, North Carolina, where Grady Cole was one of the most popular announcers at the station. There is a circa 1960 clip on YouTube of Curly performing the song with Flatt & Scruggs.

The song has since been covered by groups including Petticoat Junction, Paul Mullins & Traditional Grass, and Tom Ewing.

The second song asked about, “Worries on My Mind,” appeared on the 1971 album on the County label called Curly Seckler Sings Again. Bill Vernon, a long-time champion of Seckler’s contributions to bluegrass, offered vague clues about the song’s origins, stating that it was a “composition from the middle forties.” He had high praise for Seckler’s performance of the song: “Curly shows how well he can sing the kind of low-key, bluesy song that many bluegrass tenor singers wouldn’t be able to loosen up enough to handle, is a model of understated appropriateness.”

At the time of the recording of Curly’s County album, it was not known who the original author of “Worries on My Mind” was. Consequently, it was claimed by Curly and was published by Wynwood Music, which was owned by Bluegrass Unlimited co-founder Pete Kuykendall. Today, we know it was written by Lou Wayne, a songwriter from Beaumont, Texas, with at least 140 songs to his credit. His most popular composition was “New Jole Blon,” which was a BMI Award Winning song. “Worries on my Mind” was first recorded in 1947 by King Records artist Moon Mullican.

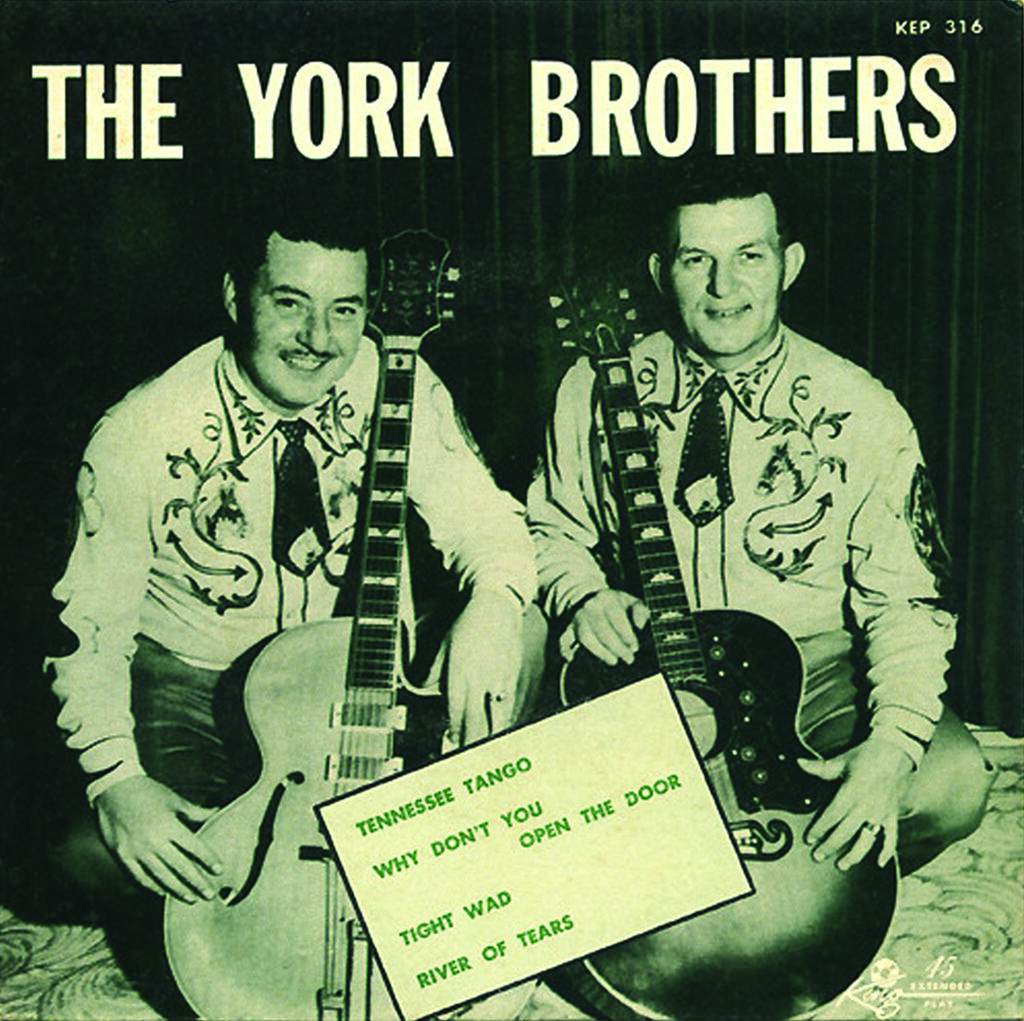

Q – The York Brothers were my uncles. I saw in Bluegrass Unlimited magazine a mention of their name in relationship to Chubby Wise. I knew Ivan Tribe and would run into him quite frequently at the Mountaineer Opry in Milton, West Virginia. For some reason, even though I talked to him about the York Brothers, Chubby Wise’s name never came up. Looking back, I would have loved knowing that so that I might have had contact with Chubby about his time with my uncles. – George York

A – From what I’ve been able to gather, Chubby played with the York Brothers for only a short period of time, most likely in the very early part of 1950.

A February 1977 article in Bluegrass Unlimited by Ivan Tribe stated that “Leaving Bill Monroe for the last time early in 1950, Chubby moved to Detroit and played briefly with the York Brothers. He then spent a brief spell with Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, then based at WVLK in Versailles, Kentucky and at Lexington’s Kentucky Barn Dance.”

In the book Bill Monroe: the Life and Music of the Blue Grass Man, author Tom Ewing likewise stated that Wise left Monroe for the last time in the early part of 1950.

In researching old newspapers of the era, the last show date I could find for Chubby with Monroe was a November 11, 1949, date in Montgomery, Alabama, that was headlined by Hank Williams. There might have been other shows afterwards, but this was the last one that could be confirmed. So, it’s possible that Chubby started with the York Brothers as early as November or December 1949 – early 1950 at the latest.

Unfortunately, I could find no advertising for the York Brothers or Chubby Wise in Detroit.

In an August 1977 issue of Bluegrass Unlimited, Carl Sauceman (of the Sauceman Brothers) was quoted as saying that “in 1949 Joe Stuart, J. P. and I went to Detroit for a few months to play in the clubs. The York Brothers had left the Opry and were doing well in some club there. Chubby Wise was with them and word got back from him. So, we just drifted up there and decided we’d make our fortune and come home. But soon I said to myself, ‘Lord, let me live long enough to get out of these clubs and I’ll never go back’.”

The 1949 date quoted by Carl might be a little off. There were advertisements for the Sauceman Brothers in newspapers in eastern Tennessee throughout the early part of 1950. The last known advertisement for a Sauceman Brothers show in eastern Tennessee was March 30, 1950. So, the earliest they would have gone to Detroit would have been April 1950.

Further clouding the issue was a statement in Penny Parsons’ well-researched book on Curly Seckler, Foggy Mountain Troubadour: “In late 1950, Carl and J. P. went to Detroit, to play in clubs on the advice of Chubby Wise, who had made a good living there with the York Brothers.”

In May 1950, advertising began appearing in newspapers in the Washington, DC area for appearances by Chubby Wise and the Florida Playboys. Chubby played in the DC for several months, from early May to August 1950.

There’s a gap where nothing about Chubby appears in print from September 1950 to February 1951, when he joined Flatt & Scruggs in Lexington, Kentucky.

Piecing together all of these threads, it appears that Chubby played with the York Brothers from (about) Dec ‘49/Jan ‘50 until March/April 1950. What his part in the show was remains a mystery.

There’s an interesting book by Craig Maki and Keith Cady called Detroit Country Music. It contains a chapter on the York Brothers and their time in Detroit. Musician Hugh Friar was quoted as saying “Chubby Wise . . . he played quite a while with the York Brothers. He played fiddle for them at Ted’s 10-Hi. This was years before [Wise] went with Hank Snow.”

Q – Recently, the song “No One to Welcome Me Home” by Larry Perkins (with Del and Ronnie McCoury) came up on my iPod shuffle and I remembered that I really like it but realized I didn’t know much about the song. I did know that there was an overdubbed Hank Williams radio recording of the same song issued in 1960, but it was issued under the name “The Old Home.” Any idea what the correct title is? – Jane Olson, Cazadero, California

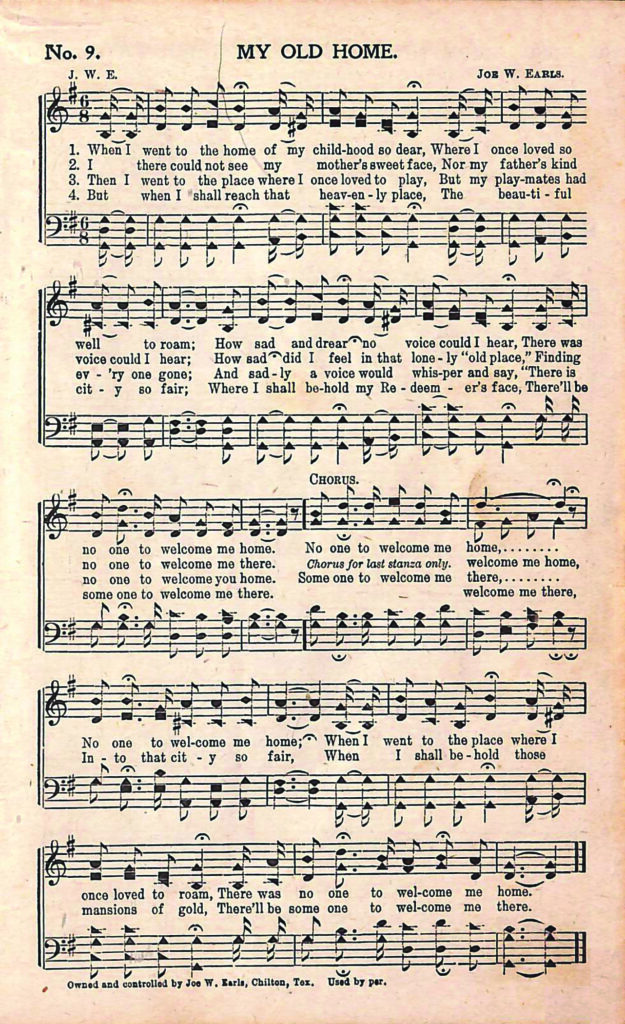

A – The song originated around 1905 as “My Old Home.” It was put together by an amateur Texas songwriter by the name of Joseph Walter Earls (February 12, 1883 – September 7, 1964). Most of his songs, about 25 of them, were listed as being composed by Joe W. Earls. Several of his compositions appeared in shaped note hymnals from the early 1900s.

Earls, a Tennessee native who moved with his family to Texas when he was eight years old (ca. 1891), enjoyed several occupations and avocations, including work as a motorman for the Waco, Texas, streetcar system, as an evangelistic singer and choir director, and as a commercial printer. He also had an interest in songwriting, especially hymns.

Earls’ process was explained in a 1962 newspaper article in the Waco Times-Herald: “Earls doesn’t exactly compose on an organ, or on a piano either. He composes in a hum. He goes around letting the words of his contemplated song form in his mind, and a tune to go with it, and hums and sings them to himself, then he likes to go to the organ and pump out the tune and write it down.”

Over the years, as different groups recorded “My Old Home,” it underwent significant changes. The most glaring change was the song’s title, which morphed into “No One to Welcome Me Home.” One of the earliest versions recorded was by the Georgia Yellow Hammers for Victor in 1929. It was the one that remained closest to the original lyrics. Recorded next was a rendering by the Blue Sky Boys, Bill and Earl Bolick. It was the lead song from their second session for Bluebird which was held on October 13, 1936, in Charlotte, North Carolina. In the early 1990s, Bill Bolick admitted that their version was somewhat of an arrangement of the original: “You can find variable versions of this song in many of the early hymn books with shaped notes. I have heard this song for years. I really think the version Earl and I sang was pieced together from parts of the song that I had heard sung by different people. The way we sing and play it, both lyrics and music, is somewhat different from any other I have ever heard. I can associate this selection with no particular individual or group.”

Other versions from the 1930s, with additional textural changes, were sung by the Delmore Brothers and the Carter Family, the latter when they appeared on Border Radio. One poignant rendition was offered by Uncle Dave Macon on the Grand Ole Opry in 1939, just a short time after the passing of his wife. The usually rollicking banjoist broke down in sobs midway through the song and had to be escorted from the stage.

In the early 1950s, two recordings were made that, years later, made their way onto records. One was an informal session that featured Uncle Dave Macon at home; it was his only time to commit “No One to Welcome Me Home” to tape. The other was a radio broadcast by Hank Williams that was saved, presumably on a transcription disc. When Hank’s label, MGM, issued the track in 1960, new instrumentation was added to give it a more modern sound. Hank’s release was one of the few that (mostly) utilized the original title; he called it “The Old Home.”

One of the most recent recordings of the song dates from the middle 1990s and is one of its few bluegrass renderings. Del and Ronnie McCoury turned in an achingly mournful reading as guests on Larry Perkins 1994 Pinecastle disc A Touch of the Past. Perkins claimed an arrangement on the song and it is, perhaps, the most distinctively different to date.

Over Jordan

David Leddell Davis Jr. (February 16, 1961 – September 15, 2024) was a singer, mandolin player, and band leader from Cullman, Alabama, who stood at the helm of the Warrior River Boys for 40 years. He was firmly steeped in the mandolin style of bluegrass patriarch Bill Monroe. He claimed a direction connection to Monroe’s music in that his uncle, Cleo Davis, was a charter member of Monroe’s 1939 Blue Grass Boys.

Davis’s musical journey began around age 8 when he discovered an old guitar stashed away in a closet. His father, despite having lost a hand during World War II, taught him the rudiments of the instrument. Additional exposure to music came from his maternal grandfather, a preacher who saw no contradiction in playing the fiddle and drop thumb style banjo. The elder also exposed young David to Sacred Harp (fa so la) singing. Coming of age in the 1970s, Davis gravitated to popular acts of the day such as Leonard Skynyrd, the Allman Brothers, and B. B. King. However, at age 18, he met two brothers who played bluegrass gospel and who were in need of a guitar player. He promptly sold his electric guitar and bought a Martin D-28. After apprenticing for a year and a half, he branched out and co-founded the Brindlee Mountain Boys.

In the early part of 1982, the Brindlee Mountain Boys shared the stage with Garry Thurmond & the Warrior River Boys. Davis was immediately taken with the professionalism of the group; so much so that he asked Thurmond for a spot in the band. The call to join the Warrior River Boys came a few months later.

Davis was hired more for his vocals than his mandolin work, which was still in development. But he persevered and participated in sessions for a tribute album to Bill Monroe. Among the tunes performed was the mandolin tour de force “Rawhide,” which happened to have been recorded while Monroe was visiting the studio. Davis later recounted the immense pressure he felt playing it in front of the tune’s composer.

By the middle 1980s, Thurmond retired from the road and passed the baton to Davis. Throughout the rest of the decade, the Warrior River Boys worked hard to establish a reputation as one of the premier traditional bluegrass bands on the circuit. A series of well-received independently released albums brought Davis and the group to the attention of Rounder Records which, in the early 1990s, issued two highly acclaimed discs: New Beginnings and Sounds Like Home.

Over the next 30 years, Davis and the Warrior River Boys rotated through a series of record companies that were enamored with his traditional approach to the music. In the late 1990s/early 2000s, disc jockey/Wango Records owner Ray Davis (no relation to David) issued My Dixie Home and America’s Music and was a staunch supporter of the group. Rebel Records chief Mark Freeman hailed David Davis as “an excellent traditionalist who never sought the limelight, but the hardcore bluegrass fans knew how good he was.” Davis’s goodness was shown on three Rebel releases: the self-titled David Davis and the Warrior River Boys, Troubled Times, and Two Dimes and a Nickel. The last of Davis’s major label releases appeared, once again, on Rounder as a tribute to old-time banjoist Charlie Poole called Didn’t He Ramble.