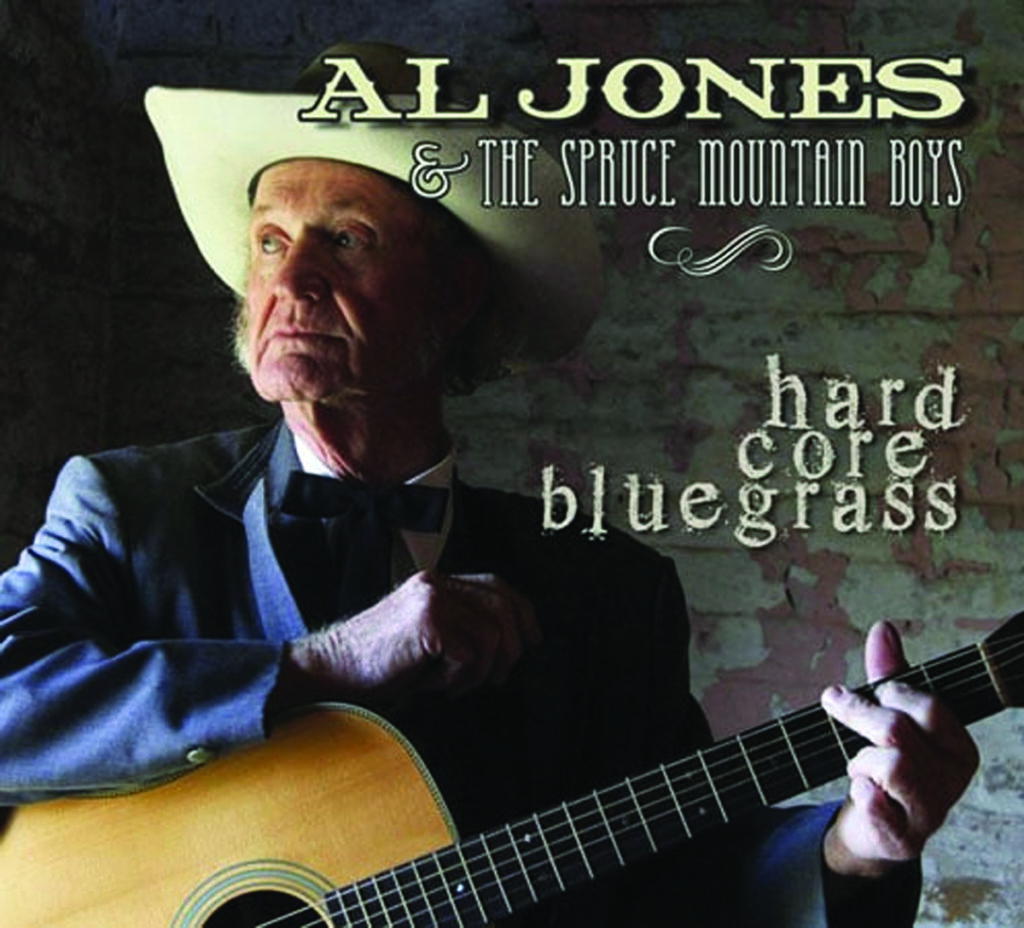

Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – May 2024

Notes & Queries – May 2024

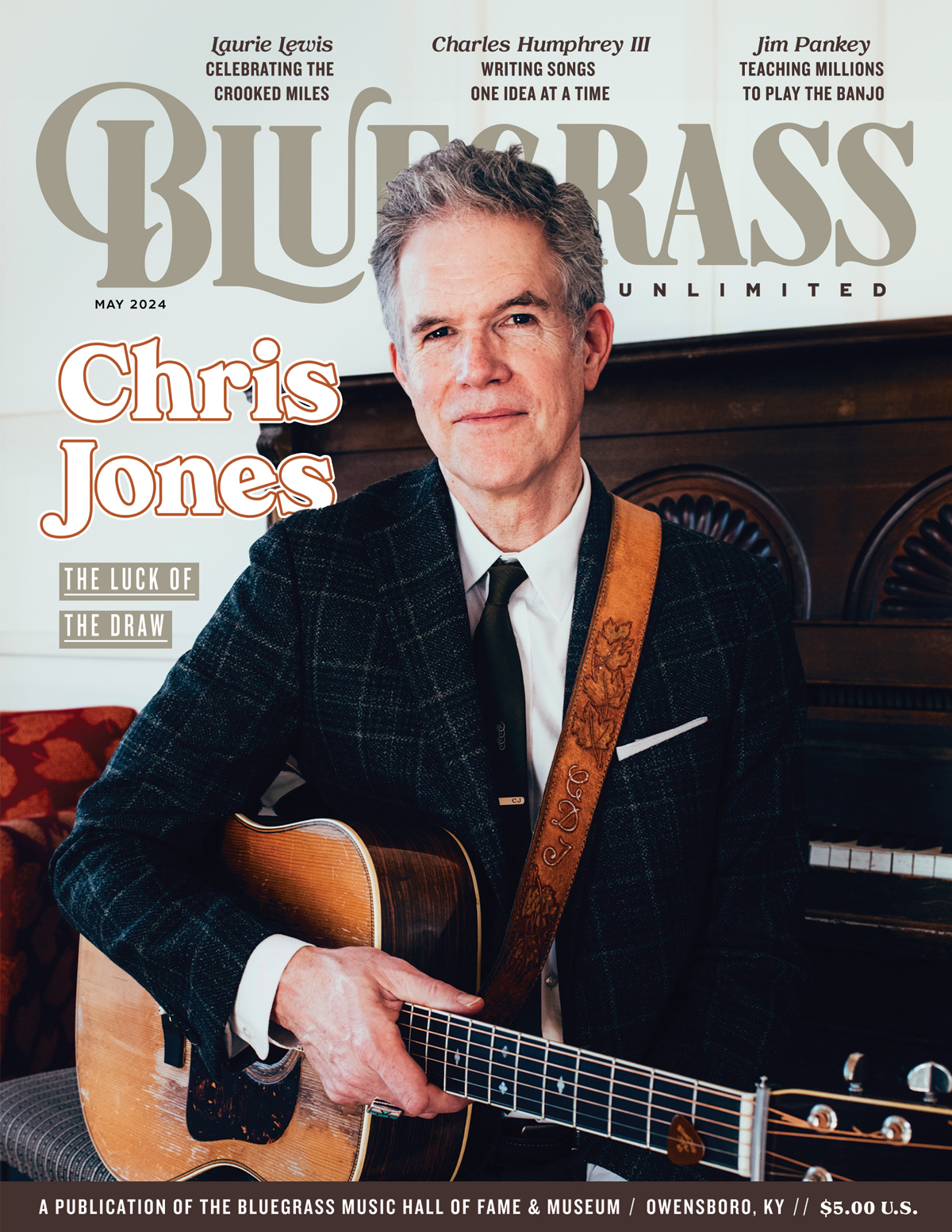

“I’ll Be True to the One I Love” – The Rest of the Story

In the June 2001 “Notes & Queries,” Walt Saunders fielded a question from a reader who was seeking the title of a song for which they recalled only a verse of lyric. The song was identified as “I’ll Be True to the One I Love” and the writers were determined to be Ike Cargill and E. Settlemyer. Walt admitted that “we haven’t found anything on E. Settlemyer.” The song was revisited again in the December 2021 “Notes & Queries” and the mystery of E. Settlemyer remained unresolved.

New research reveals the co-writer, or co-owner, to be Ervin Elmer “Vic” Settlemyer (October 29, 1903 – February 27, 1977). The song was copyrighted in the first half of 1937 with “words and music” by Ike Cargill; E. Settlemyer was listed as a claimant. Five years later, in January 1942, the song was submitted for copyright again, with both listed as the creators of words and music. Perhaps the 1942 submission corrected an error in the original application?

“I’ll Be True to the One I Love” appears to be the only song that Settlemyer ever published. A native of Roanoke, Indiana, he had an extended interest in music. In 1930, he was living in Dallas, Texas, was recently married, and worked as a salesman for the Victor Company.

By the latter part of the 1930s, Settlemyer had settled in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and his entrepreneurial spirit began to take root. In addition to copyrighting his song, he began selling jukeboxes that he ordered from the Seeburg Corporation. And, covering all the bases, he also sold cigarette vending machines.

By the dawn of the 1950s, Settlemyer had changed gears and was active in hotel management. Little else is known of his career from this point forward. He died in Oklahoma City in 1977 at age 73.

Q: Do you know who wrote the song “Sophronie” that was recorded by Jimmy Martin? Years ago, I asked fiddle player Johnny Dacus and he told me he wrote it. In 1986, I asked Jimmy Martin but he never answered my question. I’m thinking that the writer is actually Shorty Sullivan, who had a recording out way before Jimmy Martin’s version. Any thoughts? Jerry Steinberg, Salem, Virginia

A: As you mentioned, Jimmy Martin recorded the song. He did this for Decca Records at his fourth session for the label, on February 19, 1958. It was released as a single (Decca 9-30613) a short time later (March 1958). The disc credited Alton Delmore and D. C. Mullins. Billboard magazine gave a favorable review: “Lowdown hoedown gets solid reading by chanter, with vivid dance beat. Rates spins.”

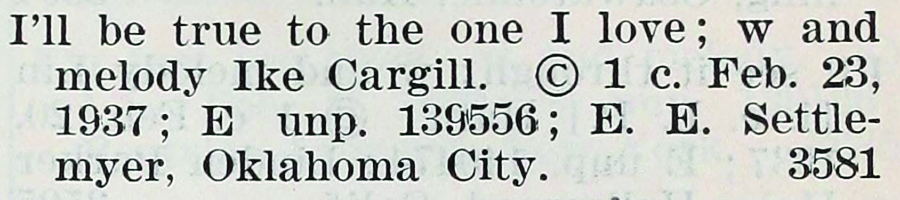

While it is true that Shorty Sullivan did release the song prior to Martin’s version, the writers’ credits remain the same. Staffers at the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville checked Sullivan’s copy of the recording and verified that the writers were Alton Delmore and Dishman C. Mullins. Sullivan’s recording appeared on the Acme label (release number 1070) sometime in 1952, or possibly early 1953. Matteo Ringressi pointed out that Shorty and Alton Delmore were label mates, they were both recording for the Acme label.

Curiously, Alton Delmore did not bother to copyright “Sophronie” until May 5, 1958, shortly after Martin’s version was released.

Philip “Shorty” Sullivan (August 24, 1926 – October 9, 1959) was a Kentucky native who was the brother of Rollin Sullivan (of Lonzo and Oscar fame). The bulk of Shorty’s professional career was spent in Alabama. His earliest known work was in June 1947 with a group called The Dixieland Boys; it was headed by another of his brothers, Johnny Sullivan. Soon, Shorty fronted his own group and was featured with a program on WVOK in Birmingham, Alabama. He was dubbed “The Alabama Champion Fiddler” and “The South’s Champion Corn Stalk Fiddler.” For a brief period of time in the early and middle part of 1949, he worked with the Alabama duo Rebe and Rabe. By year’s end, he organized the group that would be with him throughout the early 1950s, the Green Valley Boys.

An early career highlight for Shorty was the publishing of a song he co-wrote called “If You Don’t Love Your Neighbor.” It was placed with Acuff-Rose music publishers and was subsequently recorded by Carl Story and soon afterwards by Shannon Grayson.

Around the start of 1953, Shorty left WVOK and headed over to WBAM, also in Montgomery. Country Song Roundup magazine touted WBAM as “the nation’s newest 50,000-watt hillbilly station.” A popular feature of the station was its Deep South Jamboree, which was headed up by Shorty. It was during this same timeframe that Shorty hooked up for a series of performance dates in Northern Alabama with Alton Delmore. A January 1953 edition of Cash Box magazine reported on their endeavors: “Alton Delmore (King), Shorty Sullivan and the Brown’s Ferry Four are playing a number of appearances in northern Alabama. This is the first appearance of the Delmore name since Alton’s brother, Rabon, died last year.” It was likely during this tour, or a short time before or after, that Shorty learned “Sophronie” from Delmore.

Throughout the remainder of the 1950s, Shorty served as the program director at WBAM and continued to make personal appearances throughout the Deep South. He also made a few rockabilly recordings for Starday. His life and career came to a tragic end in 1959. While on tour with Lonzo and Oscar, the car in which the group was traveling was struck by an oncoming drunk driver. Shorty did not survive the crash.

While “Sophronie” co-writer Alton Delmore is fairly well-known to fans of bluegrass and traditional country music, the song’s other writer, Dishman Conley “D. C.” Mullins is largely forgotten. That’s a shame because, in his day, he was an active participant in country music.

D. C. Mullins (December 22, 1922 – January 3, 1999) was native of Spring Creek in Clay County, Kentucky. He had a dozen or so published songs to his credit including “Christmas Lipstick,” “Coffee, Coffee, Coffee,” “The Keeper of the Keys,” “Oo We Baby” and “Twelve Men and the Light.” He completed four years of high school and at age 19 (ca. 1941) was employed by the Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut. During World War II, the firm built 74 submarines and 398 PT boats. Mullins served two hitches in the Military during the war, April thru November 1943 and January thru August 1945. He served in the Merchant Marines. His initial induction noted that he was semiskilled as a welder and flame cutter.

The first hint of Mullins’s involvement in music came in 1953 when he was a news director at radio station WAIN in Columbia, Kentucky. The following year, Mullins copyrighted two songs: “Oo-Ee-Baby” and “The Keeper of the Keys.” In 1955, he collaborated with Webb Pierce – then one of the top country music artists in the nation – on a song called “Free of the Blues.” The song was recorded by several regional artists – Ted Rains and Buddy Thompson – and Mullins even went on a tour of the United States to promote the song to DJs.

In 1956, Mullins relocated to Barbourville, Kentucky, and joined radio station WBVL. There, he hosted a popular program called Hillbilly Haven. Ironically, the same year found him fronting a group called D. C. Mullins and his Rock ’N Roll Kinfolks. They even shared the stage with Reno & Smiley in the summer of 1956.

Mullins made yet another move at the start of 1957, to WGEE in Indianapolis, Indiana. In short order, he built his Country Classic show to be the city’s #1 radio program.

Jimmy Martin’s version of “Sophronie” was released in May 1958. A Cash Box reviewer touted that “not to be overlooked is the grade ‘A’ performance that Martin and the boys send up on . . . ‘Sophronie,’ a fast-paced romantic novelty delivered to a fare-thee-well. Great double-decker for the ops, jocks and dealers.” Barely a month later, it was announced that Mullins, billed as the “Ole Pipe Smoker,” was opening a new country music park: Mockingbird Hill Park. Located 20miles north of Indianapolis, the venue hosted many of the top names in bluegrass throughout the early and middle 1960s.

Eventually, Mullins’s radio career wound down and he moved back to Kentucky. In 1969, he released a 45-rpm single with two of his original compositions: “Me and Ole Blue” and “My Soldier Mind.” After that, he drifted into musical obscurity.

Over Jordan

Lendel Houston “Len” Holsclaw, Jr. (November 2, 1933 – February 19, 2024) was best-known for his decades-long tenure as the manager for the Country Gentlemen. He also contributed to the formation of the Seldom Scene and was a founding member of the International Bluegrass Music Association.

A resident of Northern Virginia, Holsclaw’s day job was as a detective for the Arlington County (Virginia) police department. By night (and weekend), he was an able bass player who often hosted jam sessions at his home. One memorable gathering introduced mandolin legend John Duffey to future heavyweight singer John Starling, thus setting the stage for the formation of the Seldom Scene.

It was only a short time later – on Labor Day in 1971 – that Holsclaw took over management of the Country Gentlemen. In addition to securing bookings for the band, he also aided in the negotiations for various recording contracts; he was a key player in landing the group with Vanguard Records in 1972. He also facilitated the Country Gentlemen’s 1975 tour of Japan.

Holsclaw’s talents were recognized early in his career when he was presented with an award for “outstanding contributions to bluegrass music” at the 1978 Labor Day Weekend festival in Camp Springs, North Carolina.

Less than a decade later, Holsclaw was in on the ground floor in the development of the International Bluegrass Music Association. Billboard columnist Edward Morris covered an early gathering of IBMA professional members where Holsclaw stressed the need for professionalism and modernization within the industry. He quipped, “You can promote an old-time fiddler, but you can’t be an old-time promoter.”

While most of Holsclaw’s professional involvement in bluegrass centered around the Country Gentlemen, he did expand the roster of talent that he represented to include singer/songwriter Randall Hylton. In a humorous nod to the (often contentious) relationship that existed between Elvis Presley and his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, Hylton jokingly referred to his own manager as “Colonel Tom” Holsclaw.

Holsclaw’s work with the Country Gentlemen spanned over 25 years. Upon the passing of the group’s central figure Charlie Waller in 2004, Holsclaw was quoted in the Washington Post as saying “He had one of the great voices in any kind of music. I stayed with him until the day he died.”

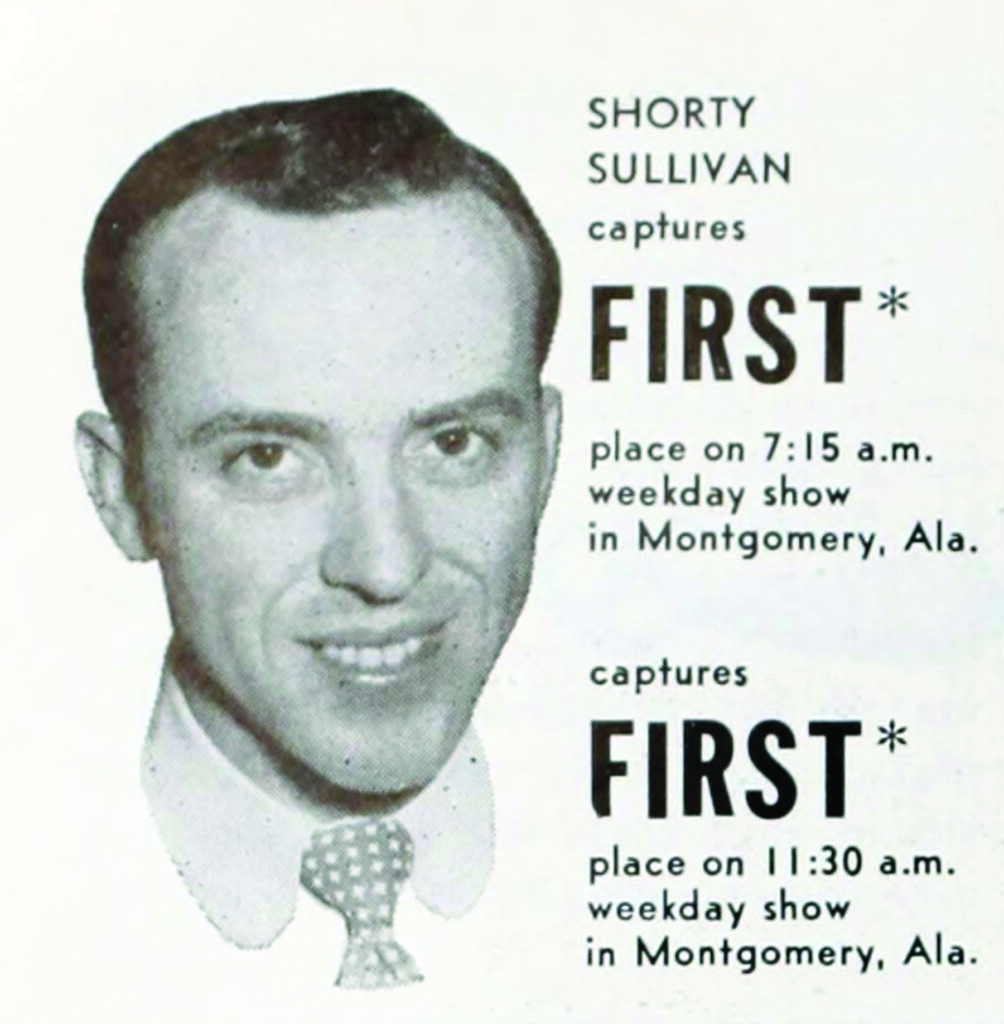

Albert Gene “Al” Jones (February 22, 1932 – March 2, 2024) was a guitarist and singer who enjoyed a decades-long partnership with banjoist Frank Necessary. Jones hailed from the Whitetop community of Grayson County, Virginia. However, as a young teen, his family moved to Maryland, ostensibly for stable employment. It wasn’t until around 1954 (age 18) that Jones took up an interest in music.

Among Jones’s first work in public was with a group headed by Eldon Stover, a younger brother of banjo legend Don Stover. In 1958, Jones joined Earl Taylor’s group in Baltimore where they played seven nights a week at Club 79. Other band members included Curt Cody, Walter Hensley and Vernon “Boatwhistle” McIntyre.

Jones’s next move came in mid-1960 when he teamed up with banjoist Johnny Whisnant. In the August 1970 Bluegrass Unlimited, Whisnant told columnist Walt Saunders that “I had met Al while we lived over in Ellicott City (Maryland). He came over there to sing, and he had Earl Taylor with him . . . and I picked some with Al over there, and Al liked the sound of it . . . We organized a little outfit . . . consisted of Pee Wee Fadre, Johnny Gall and Frank Goolsby, Al and myself . . . and we got quite a few dates . . . played some dates over in Hoverly Hall, in Baltimore, played one double-header over there with the Stanley Brothers. We played the Club Hi-Fi in Baltimore . . . a good place up there, and we played quite a few bars . . . and we had a good strong outfit.” Whisnant recalled that “Al Jones is a good man, he sings either part in a duet, and sings it great.”

Jones’s group, the Spruce Mountain Boys, came together in the early 1960s. A short time later, the band released three singles on the Rebel label and one on Pete Kuykendall’s Glenmar label. Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer Dick Spottswood pegged Jones as “almost a dead ringer for Jimmy Martin, and the songs are of the Martin type too, which is to say solid grass and very good.”

It was during this same period that Jones hooked up with his future partner, banjoist Frank Necessary. The duo was woefully under-recorded. Their most influential release was a self-titled album for Rounder that was released in 1976. A 1981 album for Old Homestead paired the duo with mandolinist Buzz Busby and the title of a 1985 release on the Webco label summed up the duo’s approach to music: Traditional Bluegrass at its Best. Despite their lack of recorded output, Al Jones and Frank Necessary logged 40 years together as a team. Necessary passed away in 2011.

Jones enjoyed a career revival in the early 2000s with several releases on the Patuxent label. A 2014 release was titled Hard Core Bluegrass while a 2018 disc paired him with Dee Gunter, a fixture of the Baltimore bluegrass scene, and fiddler Billy Baker. A third, independently released disc from 2017 was called Al Jones Sings Again – 14 Gems of Authentic Bluegrass. It matched Jones with several youthful admirers including Alex Leach and Matteo Ringressi.

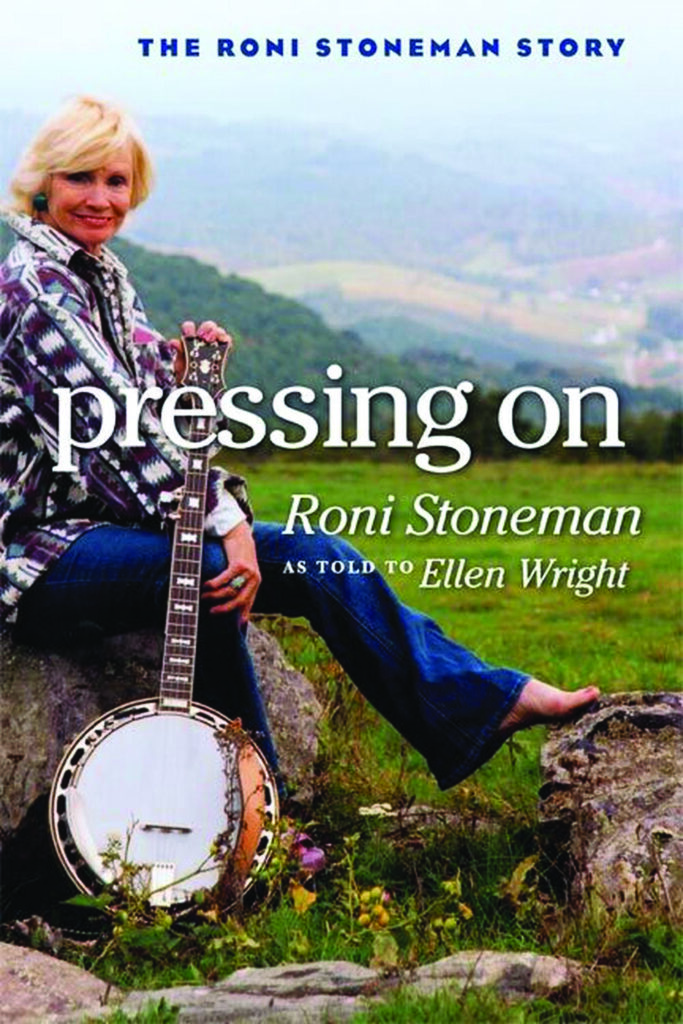

Veronica Loretta “Roni” Stoneman (May 5, 1938 – February 22, 2024) was one of the last surviving members of a country music tradition that dates back to the early 1920s. She is known to legions of country music fans for her comedic persona on the hit television program Hee Haw. She once confided that “I was put on this earth to make people laugh.” But she was so much more. To another correspondent, she said “I have always wanted to be a complete entertainer . . . to be super-duper good, and it takes a lot of work to be super-duper good.”

Roni hit the stage for the first time at age four (ca. 1942) when she appeared with her father, pioneering country musician Ernest V. “Pop” Stoneman, in a program at Constitution Hall in Washington, D. C. Some ten or so years later, her brother Scott schooled her in the basics of three-finger style banjo picking. In 1957, folklorist Mike Seeger produced the first long-play bluegrass album, American Banjo Three Finger and Scruggs Style and Roni’s contribution to the disc – “Lonesome Road Blues” – earned her the distinction of being the first female to record three-finger style banjo on a record.

Throughout the middle-1950s, Roni performed in Ernest Stoneman’s group The Little Pebbles. At the same time, her older siblings were blazing a trail through bluegrass with a band they called The Bluegrass Champs. When a spot in that group opened up for a banjo player, Roni got the job. Some of her first recorded work with the group was done in 1958, but didn’t appear on the market until 1964. The tune “Blue Grass Breakdown” was a good showcase for Roni’s developing talents.

From 1958 until 1970, Roni’s story was that of The Bluegrass Champs / Stoneman Family / Stonemans. A brief flirtation with Nashville in 1962 paved the way for two albums by the Stoneman Family for the Starday label. In 1964, the group pulled up stakes and headed to the West Coast. They found acceptance there at folk venues such as Hollywood’s Ash Grove and at folk festivals on the campus of UCLA.

The Stoneman Family returned to Nashville in 1965 for an extended stay at a nightclub called The Black Poodle. The same timeframe found the group signed to a major record label, MGM, and hosts of their own syndicated television program. When the Country Music Association launched its very first awards show in 1967, The Stoneman Family received the award for Vocal Group of the Year.

Roni left The Stonemans in the early 1970s to concentrate on a solo career. Things were shaky at first but her big break came in 1973 when she became a cast member of Hee Haw. Early on, she played the character of Ida Lee Nagger, the Ironing Board Lady. Eventually, she joined other banjo pickers as an instrumentalist on the program. In all, Roni logged 19 years with the program. One of her most satisfying take-aways from her time on the show was that it afforded her opportunity to provide her children with good educations.

The celebrity that Roni gained from her years at Hee Haw enabled her to enjoy a successful solo career that even included international travels. In 2007, she was the subject of a book called Pressing On – The Roni Stoneman Story; it was assembled from 75 hours of interviews with author Ellen Wright. Roni was active in the recording studio until relatively recently. She appeared with one track, “Going Home,” on the 2014 Patuxent Banjo Project and in 2020 teamed up with her sister Donna on a collection called The Legend Continues.