Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – March 2025

Notes & Queries – March 2025

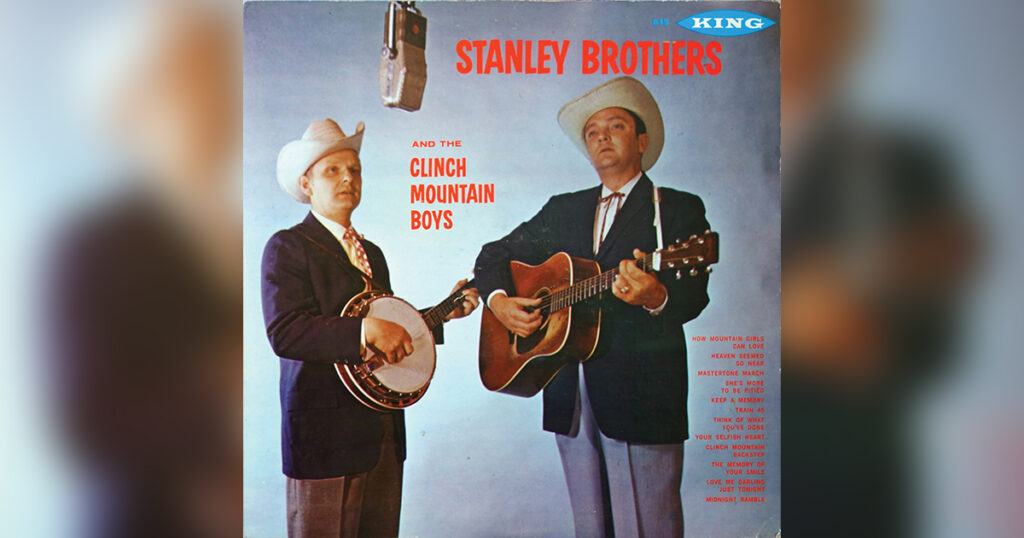

Q: I have been playing bluegrass music for at least five decades. The Stanley Brothers are one of my favorites to listen to and get inspiration from. It was recently brought to my attention by a friend, who was acquainted with Henry Dockery, that the wordage, “Get down boys, go back home…” is incorrect in the chorus of “How Mountain Girls Can Love.” It seems that EVERYBODY sings it that way; I know I have since I started playing bluegrass music. Henry Dockery corrected my friend and enlightened him to the correct wordage for that line in the chorus as “Get on board, go back home.” I’ve listened to the old King recordings, and it’s hard to pull out exactly what they’re saying. After listening to the Stanley Brothers live on the Radio Series from Ray Davis, with Uncle Henry Dockery playing bass, I’m reasonably sure it’s “Get on board.” Can you confirm the correct words? – Charles Holloway, Portland, Oregon.

A: That’s an interesting question concerning the proper words to the chorus of “How Mountain Girls Can Love.” I listened to several versions (both live and studio recordings) and a case could be made for “Get on board.” But, I think the correct words are “Get down, boys.”

First, I have a circa 1959 songbook that was issued by the Stanley Brothers. The lyrics they listed in their book were “Get down, boys . . .”

Second, I reached out to Charlie Sizemore, who sang lead for Ralph Stanley for about ten years. He replied: “I don’t think I’ve been singing it wrong. When someone says ‘get down,’ they mean for you to stop. It is still used around here (Kentucky). It comes from the time when most people rode horses (usually mules, actually). It’s a holdover. I think Ralph would have corrected me if I sang it wrong because we had to sing the same words. For example, on ‘This Weary Heart You Stole Away,’ I started out singing ‘Get ready now to love again’ and Ralph corrected me in a hurry. (It’s ‘You’re ready now . . .’).”

Given Charlie’s definition of the term “get down,” it ties together nicely with the first line of the first verse (as printed in the 1959 songbook): “Riding tonight in the high cold wind.”

And, if Charlie’s singing of “Get down, boys,” was incorrect, it sounds as though Ralph wouldn’t have had any qualms about correcting him. Two later song and picture books, both of which were issued by Ralph Stanley, contain the “Get down, boys” text.

All in all, I think it’s safe to say that Henry Dockery, a bass player/comedian worked with the Stanley Brothers in the the early 1960s, was incorrect in using the phrase “Get on board . . .”

Over Jordan

Peter Stephen “Zeke” Dawson (June 1, 1940 – November 11, 2024) was a bluegrass and country fiddler who was best known for his work with mainstream country acts including Ray Price, George Jones, Loretta Lynn, and Wilma Lee Cooper. He learned his bluegrass chops growing up in the Maryland suburbs of Washington DC in the early 1950s where his main inspiration was Scott Stoneman. Dawson acquired the nickname “Zeke” when his junior high school classmates heard him playing fiddle for a square dance. The name stuck! His first work in a band situation came when he apprenticed under Pop Stoneman as a member of the Little Pebbles.

While still in high school, in about 1956, Dawson joined the New River Boys, a group that was active in the Washington, DC area. Among the group’s regular performance venues was the Washington nightspot the Famous Restaurant. The club was located at 1215 New York Avenue, NW, a scant two blocks from the White House; it was also home base for the Bluegrass Champs (aka Stoneman Family). Other members of the New River Boys included Buddy Davis, Don Mulkey, Tom Knowles, and Johnny Hopkins; the last named was a nephew of Al Hopkins, leader of popular 1930s groups known as the Hill Billies and the Buckle Busters.

Other performance opportunities for Dawson in the late 1950s and early ‘60s included groups headed by DC local Luke Gordon; by Warrenton, Virginia, disc jockey (WKCW) Eddie Matherly (the Kountry Kings); and by disc jockey Bobby Brown (WBMD in Baltimore).

By 1964, Dawson was in Nashville where he had the opportunity to appear in the 1964 film Country Music on Broadway; he fiddled “Orange Blossom Special.” The following year, he was back in the DC area and helped out on a recording session for Bill Clifton. Along with John Duffey, Eddie Adcock, and Tom Gray, he helped lay down four songs that were best described as “English folk songs with bluegrass backing.” The songs lay dormant for several years until they showed up on a Bear Family album by Clifton called Beatle Crazy.

Dawson was hired by country singer Ray Price in December 1966. His stay in the band was likely not very long as he was reported to have been a Vietnam veteran. By 1971, he was back in the Washington, DC area working in a group billed as Harry & the Prospectors. He was also enrolled in the Catholic University School of Music.

In 1974, Dawson was tapped to be the music coordinator for a bluegrass music television series that was slated, according to Muleskinner News, “to be shown in over thirty prime markets in the eastern half of the country.” The magazine further noted that “he brings with him a lot of experience in both studio recording sessions, and television production.”

It seems that the television series never came to fruition, but in the big scheme of things it probably didn’t matter. In the early part of 1974, Dawson signed on with Loretta Lynn’s band the Coalminers. With the exception of a brief timeout to play with George Jones in the early part of 1975, he logged nine years with Lynn. The exposure generated from working in both groups earned Dawson an Academy of Country Music nomination for Fiddle Player of the Year in 1975. Other nominees included Billy Armstrong, Johnny Gimble, Doug Kershaw, and Don Rich; the award went to former Sons of the Pioneers fiddler Billy Armstrong.

During Dawson’s stay with Lynn, he appeared in the 1980 film Coal Miner’s Daughter and participated in a 1983 performance for Austin City Limits. The following year, Dawson signed on for a lengthy stay with Wilma Lee Cooper.

By 2005, Dawson had retired from touring and kept busy working with a Nashville-based bluegrass band called Leiper’s Fork. Over a ten-year period, he participated in the recording of at least two CDs: Sign of the Times and Live in Music City. In 2015, Dawson was voted Fiddler of the year for 2015 by the Magnolia State Bluegrass Association.

Liz Janssen (January 7, 1972 – January 5, 2025) Silvia Fledderus of The Netherlands contributed the following tribute in memory of Liz Janssen:

On January 5th, our dear friend Liz Janssen passed away at the age of 52. Liz, daughter of Rienk and Joke Janssen, was raised in Harpel, at the “Home of Strictly Country” (later: “Het Blauwe Huis”), the place in the North Eastern part of The Netherlands where the first seeds of bluegrass in our country were sown.

Liz grew up with bluegrass concerts in and around her house. After the old home place burned down in 2001, where her mother passed away in the flames, she rebuilt the house.

She became an artist and made major contributions to the artwork of the European World of Bluegrass, the bluegrass festival in the Netherlands where numerous musicians from Europe gathered for many years. She also designed the logo for the European Bluegrass Music Association.

Liz started singing more after she sang at her mother’s funeral. She started her own bluegrass band, Close to Home, together with her later partner and banjo player, Peter Noorman. Different musicians joined this band, and I was one of lucky ones to play and sing with Liz.

Liz had a beautiful and unique voice, recognized by the band Mideando String Quartet, and she recorded a number of fine songs with this Italian band. She performed in Italy, and later with her band at the European World of Bluegrass (The Netherlands), Greven Grass (Germany), La Roche (France) and in local venues around Harpel.

In 2011 my father, Lambert Schomaker, and I organized the Strictly Country Reunion Festival, a festival to honor Rienk Janssen’s contribution to bluegrass in Europe and to reunite readers of “Strictly Country” magazine that Rienk used to publish. For the younger folks among us, there was no internet at that time, this magazine connected bluegrass people in The Netherlands. For this special occasion Liz made a beautiful CD with a compilation of “Rienk’s Favorites” to celebrate her father’s music.

Next to singing she started playing bass, and she had a great taste in music. Next to her own songs, she had a strong preference for melodic bluegrass, like “Colleen Malone” (Hot Rize) and “Scattered By The Wind” (Donna Hughes). She heard music from the heart of bluegrass live at home when she was a little girl. Liz also found inspiration in the music of Janis Ian, Kathy Kallick, and Eminem. The range of her taste was wide and she had a good feeling of which songs fitted her voice and voices of others. Above all she had a big heart for people who surrounded her.

The last period of her life, she and her friend Peter Noorman both suffered from cancer, which turned their life upside down. In Oktober 2024 Liz had to let go of Peter, and this year, two days before her 53rd birthday she herself was taken up into the Light. Her passing broke the hearts of many; her daughter and son, her dad and her family, her close friends, and bluegrass friends from all over the world.

We are thankful for what Liz brought to our lives, all the musicians and audiences she brought in contact with the bluegrass world, the doors she opened, the way she lived her life and the heartfelt connections that will remain forever.

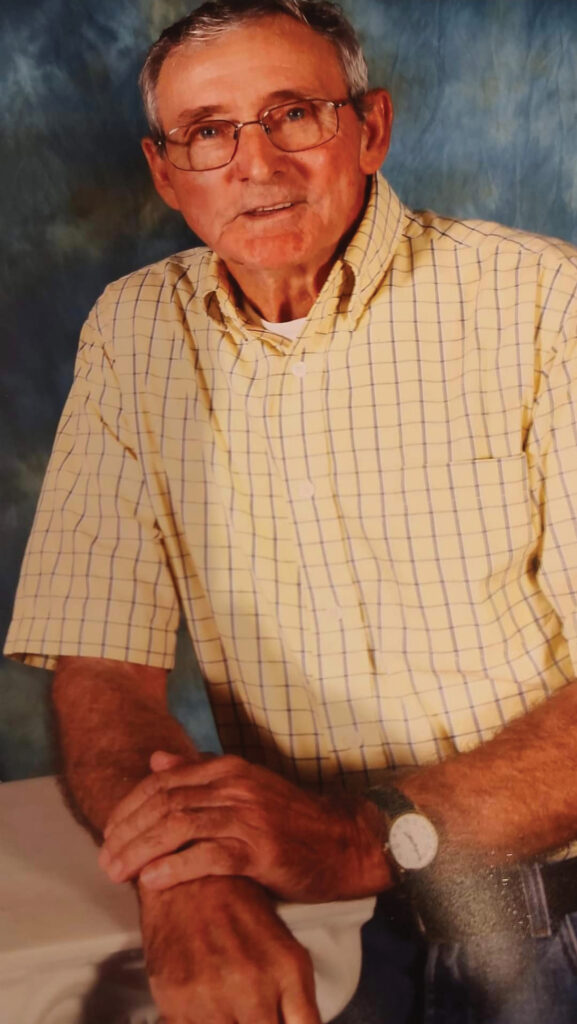

Claude “Buddy” Moore (aka Hook ‘n Beans) (December 30, 1943 – October 17, 2024) was a Kentucky-born West Virginia coal miner who enjoyed performing Stanley-style bluegrass music throughout the 1980s. He played rhythm guitar, sang lead and tenor, and had a vocal style and timbre that resembled Ralph Stanley. He first came into the limelight in the late 1970s/early ‘80s when he met guitarist Sammy Adkins. “My first cousin introduced me to him,” Adkins noted. “We were putting a clutch in a vehicle of mine . . . we were under the vehicle and Marvin (Adkins) pulled up and they started to singing. I thought it sounded a lot like Ralph Stanley. I got out from under the car and Marvin introduced me, he had a big cowboy hat on. We teamed up and started singing together.”

Moore put his talents to use in the early 1980s with stints with the Goins Brothers and Ralph Stanley. He acquired the nickname Hook ‘n Beans while working with those groups. While working with Adkins, Moore appeared on several recordings. The first was a circa 1982 gospel collection called Hand in Hand With Jesus; the band was billed as the Mountain Echoes. Moore and Adkins shared top billing on a later release called Sweetest Love. The recording benefitted greatly from past and future Clinch Mountain Boys Art Stamper (fiddle) and Ralph Hank Smith (lead guitar). Two other recordings were made with the assistance of Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys: Hook and Beans and Buddy Moore & Ralph Stanley.

Most of Moore’s work was in Kentucky, West Virginia, and southwestern Virginia. But, during his heyday, in the late 1980s, he was a favorite at Bill Grant’s festival in Hugo, Oklahoma, and at events in Texas.

Moore’s obituary stated that “bluegrass was a passion that Buddy passed down to his children, grandchildren, nephews, family and friends.” One of his daughters, Margie Wright, posted that the “last four weeks he lived, we watched Ralph Stanley videos on YouTube day and night. They were some of him and Ralph. He told many stories of his journeys around the country. Those were some of the best days of his life. I’m so proud of my daddy and his beautiful bluegrass sound that just echoes from the Appalachian Mountains. His legacy will live on every time someone plays an old Hook-n-Beans song.”

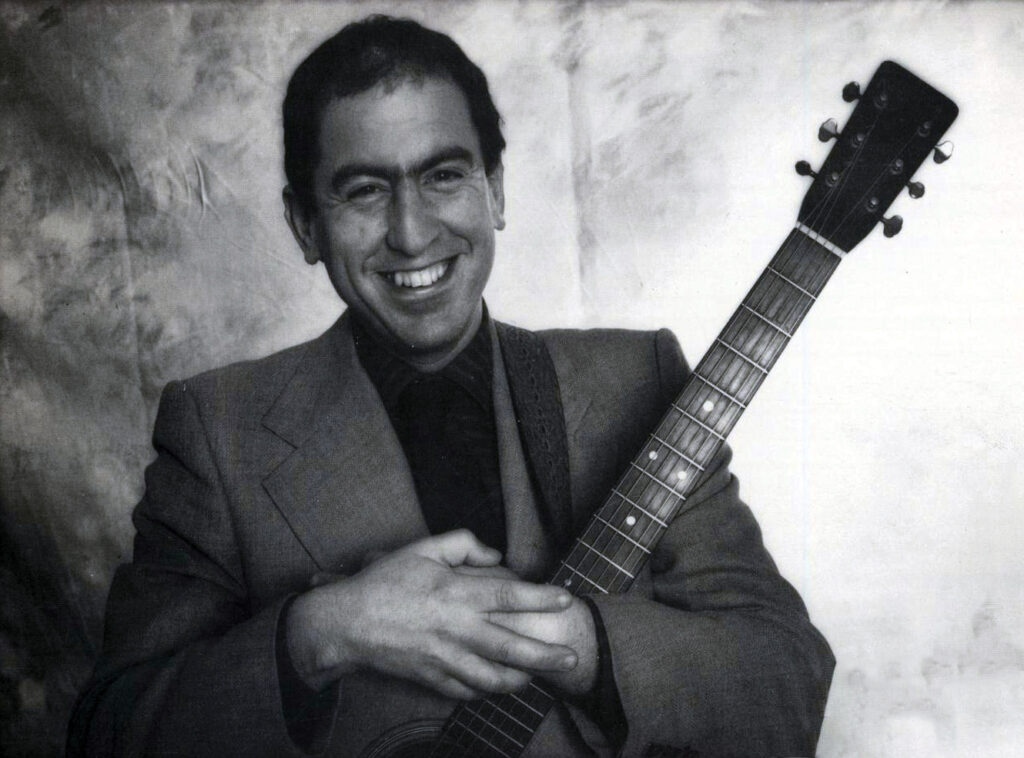

Alan Barry Senauke (December 13, 1947 – December 22, 2024) was a much-loved figure in the world of bluegrass, especially in the San Francisco Bay Area that was his home for many years. He played in a number of groups including, most notably, the Fiction Brothers, Country Cooking, High Country, and Bluegrass Intentions; he also performed as a twin guitarist with Eric Thompson. In 2006, Senauke told California’s Concord Monitor that “I’ve been playing Southern music for 45 years, but I’ll never be a Southerner. I’m a New York Jewish boy. But this is my music, it resonates in my heart and I play it as authentically as I can.”

That authenticity had its roots in jam sessions at Greenwich Village’s Washington Square Park in the early 1960s. Like many of his generation, Senauke saw music as a force for social justice.

Senauke studied English at Columbia University. After graduating in 1968, he made his way to San Francisco where he was first exposed to the Soto Zen practice that later became such an important part of his life. The area also provided him with his musical partner of many years, Howie Tarnower. The pair met in the early part of 1973 when Tarnower responded to a classified advertisement that Senauke posted looking for a like-minded musician. Enamored of old-time bluegrass duets, the new team of Tarnower and Senauke adopted the name the Fiction Brothers.

In 1974, the duo relocated from San Francisco to Ithaca, New York, where they became part of the progressive bluegrass group Country Cooking. Senauke and Tarnower received special billing on the group’s final album – Country Cooking with the Fiction Brothers – which appeared on the Flying Fish label. Where earlier Country Cooking releases tended to emphasize instrumentals, the new disc with the Fiction Brothers put the emphasis on singing. The album also benefitted from three Senauke originals: “White Fences,” “Winter Song,” and “Red Clay of Georgia.” Especially nice was a cover of Don Stover’s “Things in Life.”

Senauke’s tenure with Country Cooking was rather brief. In 1976, he took a job as an editor at New York-based Sing Out! magazine. That, too, was a short stay that lasted for only two years. In 1978, Senauke returned to Ithaca and resumed performing with Tarnower. The same timeframe found Senauke moonlighting on an album by Russ Barrenberg called Cowboy Calypso and he also found time to contribute an article to Frets magazine called “Tony Trischka – Forging a New Style for the 5-String Banjo.”

In 1980, the Fiction Brothers released their only solo album, The Chickens are Crowing. Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer Dick Kimmel noted that “the Fiction Brothers impressed me as a duo that puts as much or more emphasis on vocals as instrumentals, which is somewhat rare for a northern band. As their clever name implies, they are not really brothers at all, but two buddies who perform together (usually without a band) all over the country.”

In 1982, Senauke teamed up with Howie Turnower (mandolin), Eric Levenson (bass), and Matt Glaser (fiddle) to form a group called Leicester Flat. As today’s fans of bluegrass know from the popularity of the Earls of Leicester, that name is pronounced “Lester.” Not coincidentally, the group’s headquarters – an apartment (or, flat) – were located on Leicester Street in Boston. The group’s initial flurry of activity took place in Boston and eventually included a tour of Europe. Senauke’s proximity to the New England bluegrass scene made him available to add his guitar to the Fiddle Tunes for Banjo album by Tony Trischka, Bela Fleck, and Bill Keith.

Around 1983, Senauke moved back to the San Francisco Bay Area. It was then he took a hands-on interest in Soto Zen Buddhism. His spiritual advisor gave him the new name of Hozan Kushiki, which translates to Dharma Mountain, Formless Form. He eventually became a priest. From 1991 to 2001, he served as executive director of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship and in 2021 became the abbot of the Berkeley Zen Center.

Concurrent with Senauke’s Buddhist activities, he maintained an active interest in music. Throughout the middle 1980s, he formed the Blue Flamestring Band with Eric Thompson, Susie Rothfield (known today as Suzy Thompson), and Kate Brislin; performed as a member of the well-respected West Coast band High Country; recorded a twin-guitar album with Eric Thompson; toured Europe with High Country and appeared on two of that band’s albums; and participated at the Augusta Heritage Festival on at least two different occasions.

The early 1990s found Senauke playing with the Plum Mountain Band. He also lent his guitar playing to a recording by Station, a three-piece band from Paris, France; the group included the Senauke original “Leaving Lexington.” The middle of the decade saw Senauke’s music released on two Rounder Records collections: American Fogies, Volume One, and The Young Fogies, Volume Two.

Among Senauke’s later recordings were two projects for Bill Evans’ Native and Fine label. With Bluegrass Intentions was a band project called Old As Dirt. As a solo, he released Wooden Man – Old Songs From the Southern School. Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer Robert C. Buckingham described the latter as harkening back to a time when “good music was good music and it was less divided than today by genre and sub-genre. Senauke and friends present a fine program of music that works well, gathering strong material from old-time, bluegrass, blues, and the folk tradition into a cohesive statement.”