Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – June 2023

Notes & Queries – June 2023

Queries

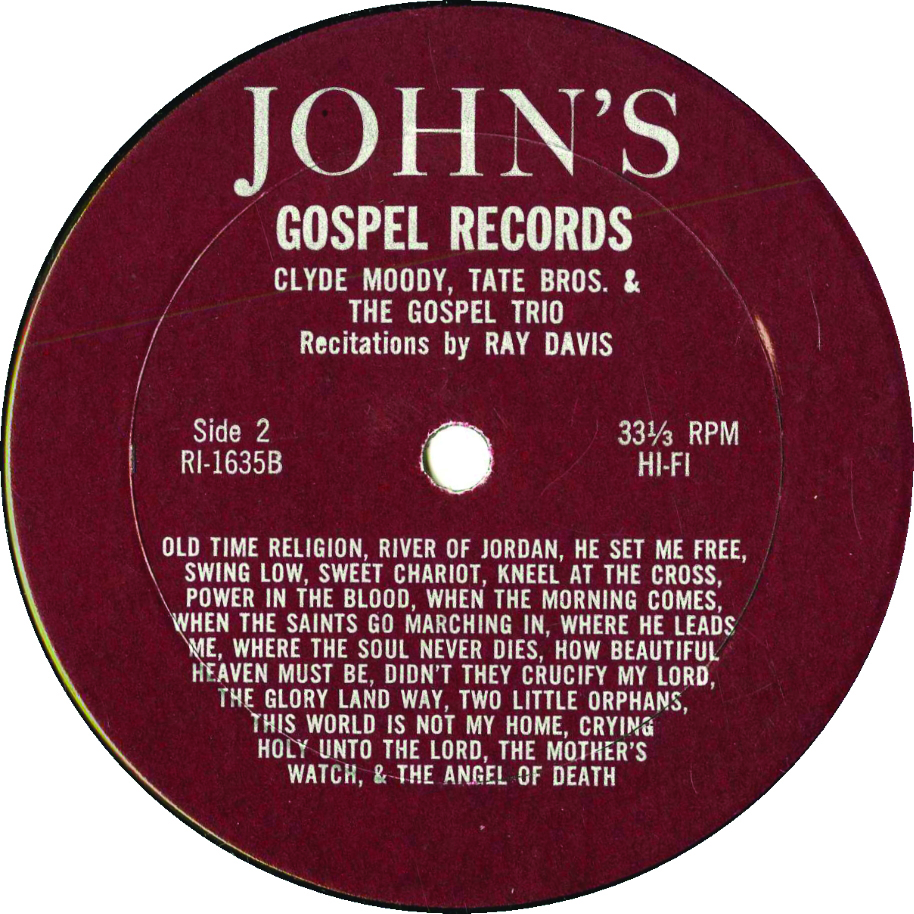

I just borrowed a copy of a release on John’s Gospel Records, RI-1635, 12” vinyl 33 1/3 RPM. Side A appears to be the Stanley Brothers with the same song list as Wango 103, while Side B is Clyde Moody, the Tate Brothers & the Gospel Trio, along with recitations by Ray Davis. There are no breaks between tracks on either side. I can’t find any reference to the label or the release number anywhere, so I’m hoping you can help out. Thanks.

—Tom Payne, via email.

A: This has to be one of the rarer albums that was produced by Baltimore disc jockey Ray Davis and his longtime sponsor John Wilbanks. Davis, of course, was also the owner of Wango Records, a label that is a famous for a series of mid-1960s moonlighted albums by the Stanley Brothers. The sessions for the albums took place in a cramped space located on the sponsor’s lot, Johnny’s Used Cars – affectionately known as “The Walking Man’s Friend.”

Most all of Ray’s recording activities were issued on his own Wango label. This particular album had the look and feel of a regular Wango release, but appeared under the imprint of John’s Gospel Records. Unlike some of the other albums that bore Wango release numbers (#103, #104, #105, etc.), this one has no label catalog number. Instead, the firm that manufactured albums for Wango – Recordings, Inc. – inserted their own identification number RI-1635 (RI = Recordings, Inc.). Comparing this number to other known RI pressings, it appears that this album was released sometime in the early part of 1964.

It’s interesting that the A side of the album contains all twelve songs that were previously released on Wango 103, John’s Gospel Quartet (later re-released on the County label as The Stanley Brothers Uncloudy Day, County 753). What’s more interesting is the B side, which alternates between tracks by Clyde Moody and the Tate Brothers. Moody is a well-known entity, but who were the Tate Brothers?

The Tate Brothers were James Lendin “Jim” Tate (April 27, 1929 – December 22, 2013) and Robert Cornell “Bob” Tate (born October 17, 1931). Bob Tate, now 91, told in a recent interview that he and his brother Jim were from “Haywood County, North Carolina, in a little town called Lake Junaluska, that’s where we were born and raised.” Jim played flattop guitar and sang lead while Bob played mandolin and sang tenor. Bob recalled that “I picked up mandolin playing with Bill Monroe because I liked his picking. That’s how I got started playing the mandolin.”

By the time Jim and Bob were eight and ten years old, they had relocated with family to the Baltimore area, mainly for the promise of steady work. Although they were too young for work at the time, Bob noted that “when the War broke out, World War II . . . there was plenty of work . . . ship building, air craft plant . . . I had some cousins that worked at Bethlehem Steel.”

In addition to Bill Monroe, the Tate boys listened to old-time duets that were popular. “We started out doing Bailes Brothers songs and the Blue Sky Boys songs and then we switched over to gospel,” said Bob.

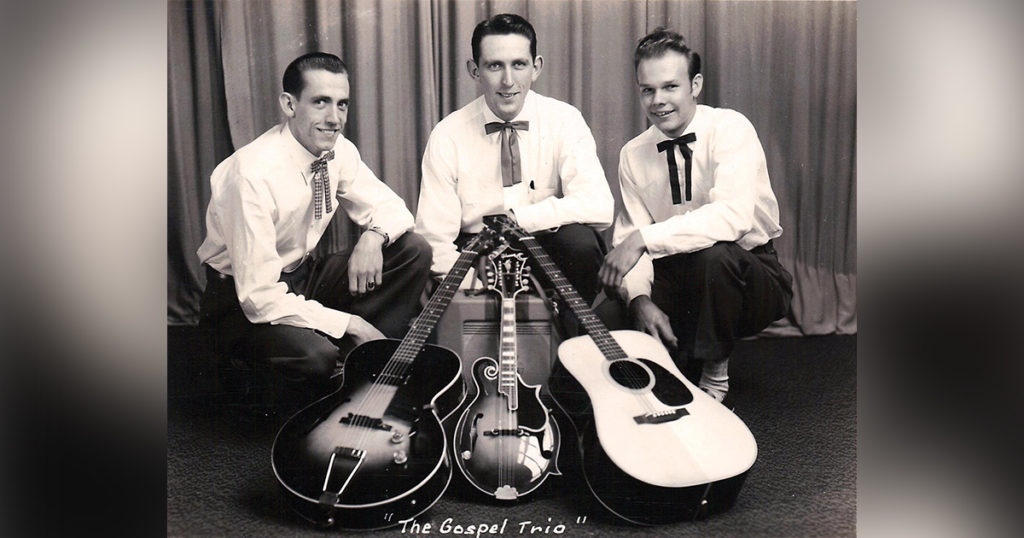

Music was always a sideline for the duo. At the start of the 1950s, Jim worked as a metal stripper in a metal factory and Bob was a machine operator in a shoe factory. The first direct evidence of the Tate Brothers performing in public was an advertisement for a show on May 9, 1954, when they were billed as a “celebrated gospel trio from Frederick, Maryland.” It was in Frederick that the group had a radio show. Of their radio days, Bob noted that “it was free time, that’s how we got that. They gave us fifteen minutes of free time [on Saturdays] so we took advantage of that. We didn’t need a sponsor, didn’t have to pay anything. I think maybe we did it maybe a year, really. Might have been a little more than that.” Their radio days were, indeed, short-lived. An advertisement for an August 5, 1956, engagement described the group as being “former radio and nite club entertainers and singers.”

Early advertising billed the group as a trio, but it wasn’t until March 9, 1958, that any mention was made of an electric guitarist, Dan Hatfield; he continued to be listed in advertising up until 1962.

The music of the Tate Brothers was often described as “country-style gospel music.” Most advertisements and articles placed the group as being from Baltimore, Maryland. One, as mentioned earlier, pegged them as hailing from Frederick, Maryland, while yet another played up their connection to North Carolina. One all-encompassing descriptor listed them broadly as “the world known Tate Brothers.”

Most of the Tate Brothers work was at religious revivals or church-related events. Bob recalled that it was “different churches around in Baltimore . . . we would go to quite a few different churches and sing. [People heard us] I guess by word of mouth. Somebody else would hear us and then they would invite us to their church.”

It was the Tate’s performance of gospel music that attracted the attention of Ray Davis and his sponsor, John Wilbanks. “We would go up to where Ray Davis worked, it was Johnny’s Used Car Lot and we would do the gospel songs at the used car dealer. And John, he wanted me and my brother to do the gospel songs of the evening on the radio station.”

The songs recorded by the Tate Brothers for Ray Davis and Wango featured rhythm guitar, mandolin, banjo, and electric guitar. Most of the tracks featured the group singing and a few were banjo-driven instrumentals. The banjo player was not a regular part of the group and their name is now long-forgotten. Songs recorded include “He Set Me Free,” “Kneel at the Cross,” “When the Morning Comes,” “Where He Leads Me,” “How Beautiful Heaven Must Be,” “The Glory Land Way,” and “This World Is Not My Home.” The selections alternated between driving banjo numbers and slower ones with mandolin and electric guitar. As far as is known, these are the only commercially released recordings by the Tate Brothers.

Advertising suggests that the Tate Brothers continued to perform together until the latter part of 1973. At the same time, Jim and his daughters, Debra and Shari, began performing together as the Tate Family. Bob, on the other hand, joined with several pickers – a number of which were military men – to play bluegrass. Bandmates, at times, included Jim Duke on bass, Les Holmstead on guitar, Mills McNeal on guitar, and Kimble Blair on fiddle.

Jim Tate passed away on December 22, 2013.

Over Jordan

Dwight Hamilton Diller (August 17, 1946 – February 14, 2023) was a masterful clawhammer banjo player and teacher. A 1997 edition of Sing Out! magazine called him a “guardian of traditional West Virginia mountain music.” Others touted his works as a historian, philosopher, and Mennonite pastor.

Although born in Charleston, West Virginia, Diller grew up in Pocahontas County, which is located in a southeastern corner of the state. His family ties there date back to the late 1700s. It was his connection to the land and the people that led him to seek out older generations of West Virginians who learned their music, and stories, in the days before radio and records became commonplace.

Among the earliest tradition bearers that Diller met was the Hammons family, in 1968. Several years later, he introduced them to the Library of Congress, who subsequently issued a two-album set of the family’s recordings, complete with a forty-page booklet. Musical gatherings that Diller initiated became the basis of further Hammons releases, most notably 1973’s Shaking Down the Acorns.

It was about the same time that he met the Hammons family that Diller began to play music. In September 1969, he received his first – and only – official music lesson, from musician Dick Kimmel. Diller went on to develop a very intense style of playing that Kimmel later referred to as “sledgehammer banjo.” In a 1996 issue of Banjo Newsletter, Diller acknowledged that “I want to play music that comes together real strong and it’s like winding up a coil spring real tight and having that tension in the music.”

Although basically an old-time musician, Diller logged six years as the bass player in the West Virginia-based Black Mountain Bluegrass Boys. He appeared on three of the group’s albums: Pure Old Bluegrass, 1971; Million Lonely Days, 1973; Talk of the County, 1975; and one retrospective collection called 1968-1973, 2000.

Diller began teaching old-time banjo to others, starting in 1971. He continued to do so for most of the next fifty years. The notes to one of his CDs told that “Dwight Diller has taught and played the old 19th and 18th century music all of his adult life. He spent countless hours learning and absorbing from the old people who were his friends, relatives, and neighbors. Having paid his dues, Dwight is now part of a tiny minority of home-growns who are carrying the authentic tradition into the 21st century.”

Other career and personal highlights include his conversion to Christianity in 1976, the earning of two masters degrees (one in horticulture from West Virginia University and another from Eastern Mennonite University), becoming a Mennonite minister in 1984, being featured in Banjo Newsletter and Sing Out! magazines, forming a record label (Yew Pine Music) for the release of a dozen albums of his music, and representing West Virginia in the 2003 Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, DC. Diller’s most recent, and perhaps most prestigious, recognition of his talent came in 2019 when he received the Vandalia Award, West Virginia’s highest folklife honor. The prize recognizes that “the individuals who receive this award embody the spirit of our state’s folk heritage and are recognized for their lifetime contribution to West Virginia and its traditional culture.”

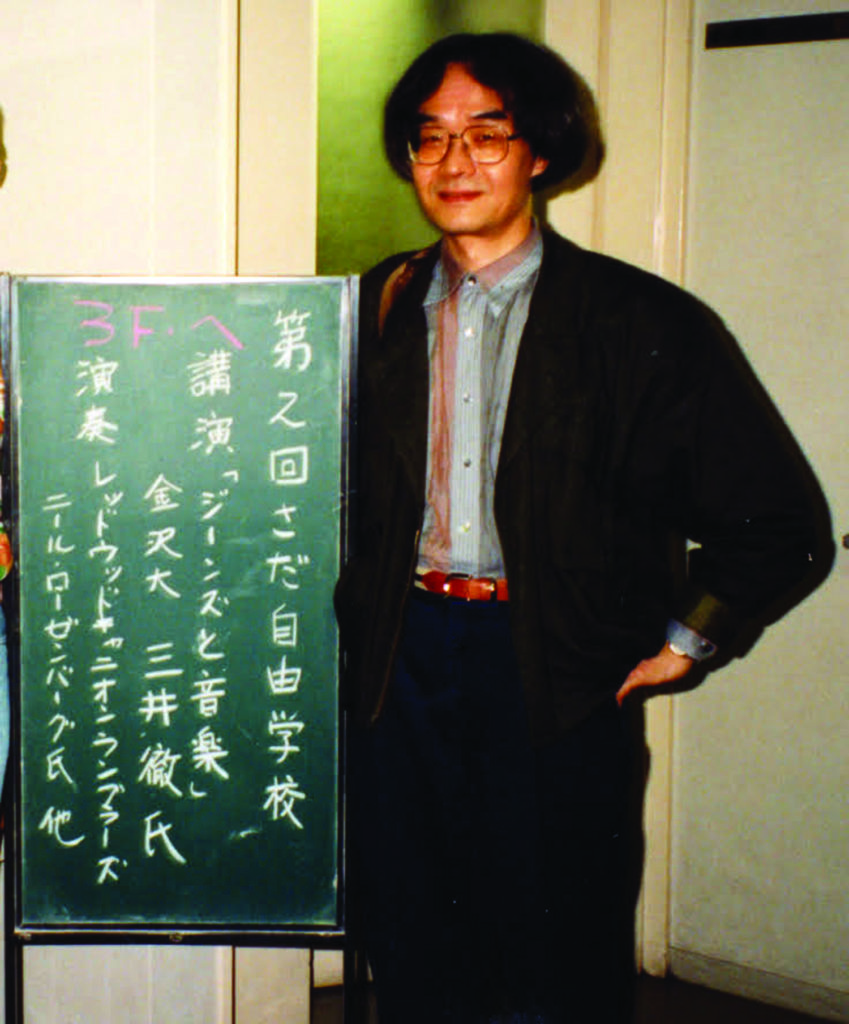

Toru Mitsui died on February 19, 2023. He was 82. Born on 31 March 1940, in Saga, Kyushu, son of a University of Kyushu professor of English, his life in music began early. While studying at Seinan Gakuin University in Fukuoka, he played lead electric guitar in a Fukuoka dance band with fellow college students, doing rock and roll, country, Hawaiian and contemporary pop. One of his bandmates was Tsuyoshi Hashimoto, a childhood friend with whom he’d long shared an interest in music. At University, they became attracted to American folk music. They even put together a bluegrass quintet, Kentucky Highland Folks, for a concert in 1961.

Toru followed this interest not only as a performer but also a scholar. His Batchelor’s (1962) Master’s (1964) theses were about traditional English ballads. Following this training, he began his academic career as a lecturer at Aichi University in Nagoya. His performing continued as he conducted research and lecturing on Anglo-American folksong.

I met Mitsui in June 1966, soon after he arrived at Indiana University in Bloomington to study at the Folklore Institute where I had just become an employee. It was a pleasant surprise to discover that he knew so much about American folk music.

Mitsui and his wife Takako stayed in Bloomington until early 1967. I took him to Bill Monroe’s Brown County Jamboree in nearby Bean Blossom several times. He would later draw from his diary and photos to describe that experience in Moon Shiner. In August 1966, the Mitsuis traveled to the east coast, where they first attended a big folk festival in upstate New York, Fox Hollow. Next, they went to Greenwich Village in New York City to visit The Folklore Center and meet its legendary proprietor, Izzy Young. Finally, on Labor Day weekend they came to Cantrell’s Horse Farm in Fincastle, near Roanoke, Virginia, to join us at Carlton Haney’s second annual bluegrass festival. There they saw Bill Monroe, The Country Gentlemen, Don Reno, Red Smiley, Mac Wiseman and many other famous bluegrass pioneers.

In the fall of 1967, his Bluegrass Music — the first book ever written about bluegrass — was published. It included photos from the Haney festival and Bean Blossom. When its revised edition appeared in 1975, Bill Monroe’s autographed endorsement, which he wrote for Toru while performing in Osaka, was on the title page.

In 1969 Mitsui moved to Kanazawa University, where he taught until his retirement in 2005. During his career he became one of the world’s leading scholars in the field of Popular Music Studies. He was a prolific writer, publishing over twenty books, forty academic papers and close to 500 articles in commercial and independent journals. He also wrote notes for 135 LP and CD albums, and made sixty radio and television appearances. Moreover, he translated many books and articles.

His most important English book is Popular Music in Japan: Transformation Inspired by the West (New York: Bloomsbury, 2020). Its final chapter (7, p.149) gives a history of bluegrass in Japan, a reflection of his continuing love for this music.

Over the years we kept in touch by mail and email, met at academic conferences, and visited each other’s homes. Mitsui hosted my parents when they visited Kanazawa and later, during his visits to Berkeley, California, would stay with my father. In 1990, at a party celebrating my father’s 80th birthday, Toru suggested to me and my bandmates in the Redwood Canyon Ramblers, Northern California’s first bluegrass band (1959-63), that because we were the first bluegrass band Jerry Garcia heard, we might find an audience in Japan.

This led to our 1991 reunion tour of Japan. With the support of Sab and Toshio at BOM, Mitsui was the Redwood Canyon Ramblers’ manager, emcee and tour guide. We played 10 gigs, beginning in Kusu in O’ita on Kyushu, and ending in Kanazawa. A set at the Tokoshima Bluegrass Festival, where he introduced us, can be seen on YouTube. We were joined there by the great Dobro player Sato and bassist Ueda: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T-tfDfT_4Uo)

After his retirement he reunited with his old friend Hashimoto, releasing CDs of their 1960s folk and bluegrass performances, which received a good review in The Journal of American Folklore. In June 2007 they appeared at the IBMM’s ROMP festival. Their performance was reported on the front page of the Owensboro daily newspaper.

Toru Mitsui was truly one of a kind. He was an accomplished musician, outstanding scholar, and a very good friend. I’ll always remember his kindness and the happy times we had together during our visits and travels. With this message I send Japanese bluegrass fans these thoughts of condolence: We grieve the loss of a unique friend but can be happy that he left so much fine music and great writing for us to appreciate and continue to enjoy. That nurtures our memories.

– Written by Neil V. Rosenberg

St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada

Ronald L. “Ron” Spears (July 28, 1953 – March 22, 2023) was a much beloved, jack-of-all-trades bluegrass musician and songwriter. Known as a friend to all, he possessed a keen, upbeat spirit, was fond of telling jokes, was a yoyo champion, and loved entertaining little folks with his ventriloquist act.

A native of Utah, he grew up on the sounds of rock ‘n’ roll but edged his way to country and bluegrass music in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. Pivotal moments included seeing guitarist Don Rich with Buck Owens and catching the Osborne Brothers on The Country Place television program that was hosted by Jim Ed Brown. After seeing the latter group, Ron ditched his electric guitar for a five-string banjo. Throughout the early 1970s, he played in several groups, including Obadiah’s Organic Bluegrass Band, Organic Greens, and Cottonwood.

In the middle 1970s, Ron began a twenty-plus year ride as a bus driver for the Utah Transit Authority. During frequent layovers between routes, he passed the time by playing various instruments that he brought from home. It was also the start of his fledgling career as a songwriter. In 1993, after years of accumulating songs he’d written, Ron began making and sending out demos. The following year, he attended IBMA’s World of Bluegrass trade show and handed out demo tapes. Response was slow at first but in time he registered forty-six songs with BMI and counted IIIrd Tyme Out, David Parmley, Special Consensus, Josh Williams, Lou Reid & Carolina, Fast Track, Justin Carbone, the Bluegrass Cardinals, Doyle Lawson, and the Bluegrass Patriots as friends who made use of his original songs.

The middle and late 1990s were witness to the evolution of Ron Spears, the band leader and performer. In 1995, he formed Within Tradition and won the Northwest Pizza Hut Championship. Two years later, he recorded his first solo outing called My Time Has Come; it was comprised mainly of his own original songs. He closed out the decade by working as a guitarist for Rhonda Vincent and the Rage.

With the start of the new millennium, Ron reorganized Within Tradition. He and the group showcased for IBMA in 2000. In 2001, the group released its first band album, Grandpa Loved the Carolina Mountains. The California Bluegrass Association named Within Tradition as the organization’s Emerging Artist of the Year. A second band project was called Carolina Rain.

By 2007, Ron had relocated to Nashville where he secured employment with Gaylord Entertainment, owners of the Opryland Resort and Conference Center. But making music remained a healthy part of the mix and in 2007 alone he logged time with Special Consensus, Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver, and with David Parmley and Continental Divide. He took time out in 2009 to tour with the James King Band but eventually returned to Continental Divide.

Ron was on-hand in 2015 when David Parmley transitioned from Continental Divide to Cardinal Tradition. When David retired in 2019, the band remained together under the new name of Fast Track. Members included Dale Perry on banjo, Ron Spears on bass, Steve Day on fiddle, Shayne Bartley on mandolin, and Duane Sparks on guitar. The group recorded two albums together, the self-titled Fast Track and a gospel outing called Good News.