Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – July 2024

Notes & Queries – July 2024

Q: I was a big fan of the Greenbriar Boys and was good friends with all of them, especially John Herald. Listening again to some cuts recently I came across “Way Down in the Country.” I assumed it was a Grandpa Jones tune because it sounds exactly like something he’d do. But I can’t find any other version of it, except as an autoharp instrumental, of all things. Do you have any info on this tune? James Field, via email.

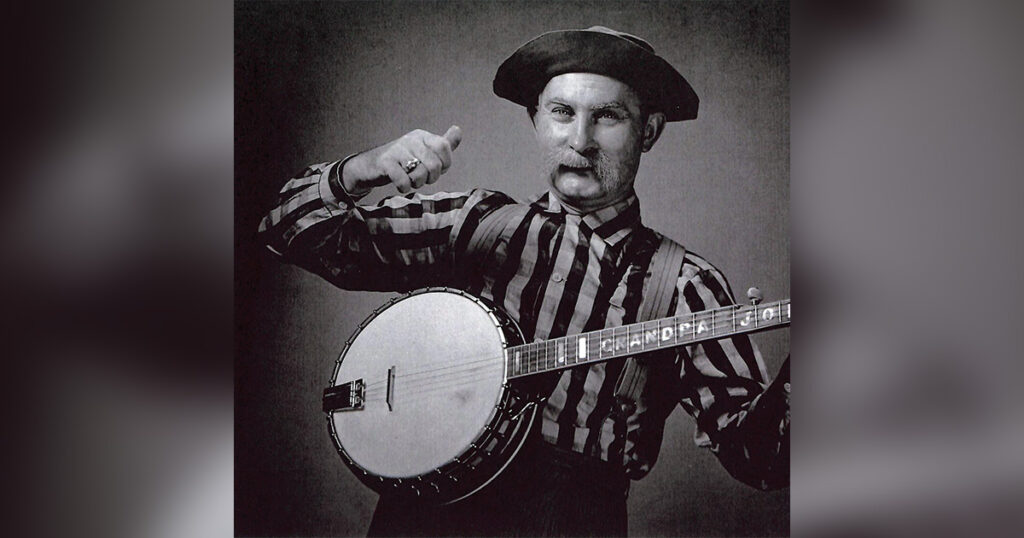

A: Your instincts were right on! “Going Down the Country” was recorded by Grandpa Jones for King Records in 1947. Composer credits on the original King 78 rpm disc list “Jones – Scott.” Jones, obviously, was Grandpa. Scott was a pseudonym for Alton Delmore of the Delmore Brothers.

The song was cut at Grandpa’s eighth session for King Records. Given Jones’s attachment to the banjo, it’s hard to imagine today that this was his first session to feature any 5-string banjo picking. Up until that time, on record, he had been a guitarist and a featured vocalist. Of the five songs committed to disc at his 1947 recording session, only two featured his banjo: “Mountain Dew” (which went on to become one of his signature tunes) and “Going Down the Country.”

In Jeffrey J. Lange’s 2004 book, Smile When You Call Me a Hillbilly: Country Music’s Struggle for Respectability, 1939-1954, Jones explained his rationale for recording with the 5-string banjo: “The greats who played old-time banjo, like Uncle Dave Macon, couldn’t get recorded during those years – the sound wasn’t ‘modern’ enough. But I knew from my mail and from my fans at shows that they did like my old-time frailing banjo style, especially on fast numbers . . . About that same time Earl Scruggs had been playing his new bluegrass banjo with Bill Monroe, and they were going over well on the Opry and on records, so I thought that I might try recording a little old-time banjo playing.”

Helping out on the session was the duo of Homer & Jethro and Grandpa’s wife, Ramona Jones. Although Homer & Jethro are remembered today mostly as a comedy team, they were very capable musicians. In fact, when signing autographs, Jethro Burns frequently added the initials TWGMP after his name (The World’s Greatest Mandolin Picker.) Playing bass was Leonard Sosby, a member of radio station WLW’s Trailblazers group.

Billboard magazine was less than enthusiastic about “Going Down the Country.” They called it a “Fast stepping hill tune. Guitar and banjo strumming on the dull side.”

Q: Do you happen to know how many songs Bill Monroe wrote throughout his life? I read that Hank Williams wrote roughly 167 songs. Wayne Hoffman, via email.

A: According to BMI, Bill Monroe has 278 songs to his credit. However, reading numbers such as these can be tricky. Included in Bill’s catalog of songs and tunes are traditional pieces that he arranged or simply claimed as his own. In other cases, it was not uncommon for performers to buy songs from other writers and then copyright them in their own names. Such was the case of “How Will I Explain About You,” a song that Monroe purchased from Arthur Q. Smith and recorded for Columbia Records in the middle 1940s. Another practice that was common in the 1940s and ’50s was the adding of a performer’s name to a song as a perk for recording and popularizing it. An example of this is the song “Country Waltz,” which was written by South Carolinian Claude Breland. In March 1951, Monroe performed in Charleston; at the show, Breland gave Monroe a copy of a song he had written two or three years earlier, “Country Waltz.” Monroe recorded the song for Decca Records in 1952 and released it in 1953. Song credits on the record listed Claude V. Breland AND Bill Monroe. Did Monroe actually contribute to the final composition of the song? Or was this merely a case of Monroe adding his name as compensation for popularizing the song?

Although the reader’s query was about songs by Bill Monroe, it’s interesting to note the number of songs credited to other first-generation bluegrass performers: Lester Flatt, 177 songs; Don Reno, 231 songs and tunes; Earl Scruggs, 175 songs and tunes; Carter Stanley, 108 songs (plus 20 songs written under the pseudonym of Ruby Rakes); and Ralph Stanley, 220 songs and tunes.

Over Jordan

Loek Lamers (April 12, 1931 – May 11, 2024) was a great promoter of Bluegrass music in the Netherlands. In the early 1960s, he was introduced to Bluegrass by the radio broadcasts of the American Forces Network in Europe. His work occasionally involved trips to the United States where Loek had the opportunity to see and hear the music firsthand. In his spare time, he visited concerts and festivals and came in contact with many of the big stars.

In 1972, Loek invited Bill Clifton for a concert close to his home; ten years later he invited the Sullivan Family. From 1990, when he was retired and started living a more regular life, he organized one or more concerts each year, generally with an American group. Among those he hosted were White Mountain Bluegrass, Charlie Louvin, Bob Paisley, Tammy Fassaert, Front Range, Skip Gorman, Laurie Lewis, Valerie Smith, Sally Jones, Special Consensus (five times), Lost Highway, James King, Monroe Crossing, Level Best and many others. People of various ages – from young to old – came to enjoy the music. And they came to listen. It was often dead quiet in the room when the bands were playing.

In the meantime, Loek got a radio program at several local broadcasters. He filled one hour every week with traditional country and one with bluegrass. Because of his knowledge of the music, his listeners enjoyed both the music and the information. He made his last broadcast about a year ago when the station wanted to take a different course.

Loek played mandolin and autoharp in a band called Brakwater that was composed of other music lovers from Hoorn, the town where he was born. The band played a mix of country and folk, with a little bluegrass. One of Loek’s favorite tunes that he played on the mandolin was “The Cuckoo Waltz.” Sadly, the group did not make any recordings. Two years ago, Loek donated his mandolin to Arnold Lasseur of the group Blue Grass Boogiemen.

Loek was a member of the IBMA and attended the annual conferences many times. He also served as a jury member at the La Roche bluegrass festival in France. He leaves behind a room full with LPs and CDs, but most of all a close family, consisting of his wife Hannie – who used to cook a good dinner for the performing artists – his four daughters and eight grandchildren. And a lot of good friends, who will not easily forget him. (Submitted by Hans van der Veen, a bluegrass disc jockey and good friend.)

Beverly Diane Bretz “Bev” Paul (September 15, 1947 – April 19, 2024) was not someone whose name rolled off the tongues of most rank-and-file bluegrassers. Yet, her presence, her deeds and her work were felt by many. From 1991 until 2007, Bev was responsible for marketing and sales at Sugar Hill Records.

Bev was raised in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, which she characterized as a Moravian settlement. While her family was not necessarily musical, her father had an appreciation for big bands of the 1930s and ’40s. As a teen, a chance exposure to a Kingston Trio album set Bev on a life-long appreciation of folk and roots music. Folk icons of the day (Baez, Dylan, Collins) and deep catalog favorites (Leadbelly, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Pete Seeger) soon became part of Bev’s musical lexicon.

Not being musical herself, Bev toyed with a career as an ethnomusicologist but instead wound up with a degree in history. A move to North Carolina exposed her to that state’s robust folk and traditional music scene.

Over the next twenty years, Bev worked a series of jobs that gave her a well-rounded, hands-on understanding of the inner-workings of the music industry. First, there was the Gaslight listening room in Fayetteville, North Carolina. As manager, Bev did everything including hiring the talent, working the door, making announcements and cleaning up after the last patron had left for the evening. The gig ended when the Gaslight was unable to renew its lease.

After a brief detour as a customer service agent in the repair shop of a car dealership, Bev landed at radio station WQDR in Raleigh, North Carolina. It was run by Lee Abrams, who is credited with launching the Album Oriented Rock (AOR) format that was emulated by hundreds of other stations. Bev was the station’s promotions director. In September 1984, the station adopted a country format and Bev was temporarily without a job.

WQDR’s program director made the move to Record Bar, then one of the largest music retailers in the country, and they encouraged Bev to apply as well. At Record Bar, Bev was a buyer – one of only two who actually liked country music. There, she learned all about inventory control and the mechanics of seeing merchandise through to its ultimate destination — a consumer’s hands. As had happened several times previously, changes in ownership left Bev unemployed. Such was the case when Record Bar moved its headquarters to Atlanta.

When Bev approached Sugar Hill Records owner Barry Poss for a job in 1991, she brought a unique understanding of the music world with her. A music world triple threat, that intellect included her work with the public and artists as a venue manager, with radio promotions, and with music distribution and sales. Those assets fit perfectly in her roles of marketing and sales.

Straightaway, Bev went to work streamlining the process in which new releases were announced and distributed to press, media and buyers. Having been a buyer, she knew the right words to use in reaching out to distributors. Knowing that a key part of getting more people to buy Sugar Hill product was to make more people aware of it, Bev became an active participant in the International Bluegrass Music Association; she served two terms as a board member: 1996-1998 and 2001-2003. It was her initiative that prompted mass retailers such as Borders Books and Wal-Mart to attend IBMA trade shows.

Under her watch at the label, she oversaw high profile releases such as Nickel Creek’s double-platinum debut and three bluegrass/acoustic country releases by Dolly Parton. Other successful bluegrass outings included those by the Gibson Brothers and banjoist Jim Mills.

Bev also worked at developing a knowledgeable and enthusiastic staff, often teaching them the business of music from the ground up. Typical of the loyalty and appreciation generated by those who worked and studied under Bev is Judy McDonough, a veteran publicist who is known through her work at Sugar Hill Records, MerleFest and IBMA’s World of Bluegrass event. She related recently that “when Barry Poss hired me at Sugar Hill Records in 1992, I had tremendous enthusiasm, great writing skills – and zero experience as a publicist. What a blessing that Barry and Bev invested the time and effort into teaching me how to be a professional in the music industry; 32 years later, I still earn my living doing PR. Bev knew the industry inside and out, and gave me excellent advice about working with artists and media. To have worked and learned under such a respected, creative and intelligent woman in that industry was truly a gift. Bev Paul was a huge influence on me and many other women; she generously shared her experience and knowledge with so many of us.”

In 1999, Bev was part of discussions for “collective action that could help the Americana community.” This led to the formation of the Americana Music Association. She was also a 2003 graduate of IBMA’s Leadership Bluegrass program.

In 2007, Sugar Hill’s offices were consolidated in Nashville. After 16 years with the label, Bev took this opportunity to make her exit from the firm. For the balance of her career, Bev worked as an independent music business consultant. Her clients included MerleFest and Scott Miller, a Southern rock and alternative country singer, songwriter and guitarist.

Charles E. “Chuck” “Bubba” Wentworth, Jr. (July 4, 1951 – April 25, 2024) was a fixture of the bluegrass and Cajun music scenes in the northeast for over 40 years. During that time, he served as the Folk & Roots Music Director at WRIU-FM in Kingston, Rhode Island; was a co-producer of the long-running Cajun/bluegrass music festival in Escoheag, Rhode Island; coordinated the early IBMA Fan Fest events; was a Winterhawk festival organizer; served on the Bluegrass Museum advisory board; served on the IBMA board of directors; was the talent buyer for the Grey Fox festival; and partnered with Mary Tyler Doub to produce the Rhythm & Roots festival in Charlestown, Rhode Island.

Wentworth was a 1977 graduate of the University of Rhode Island. He then logged over 30 years as an Aquaculture Scientist in the school’s Aquaculture and Fisheries Science department. The start of his work at the university coincided with his discovery of bluegrass. In 1978, he attended the Berkshire Mountain Bluegrass Festival in Ancramdale, New York. That same year, he joined the staff of WRIU as an on-air personality. He eventually became the station’s Folk & Roots Music Director. When Bluegrass Unlimited launched its National Bluegrass Survey, Wentworth became one of the early disc jockeys that reported to the chart. His program at the station remained on the air until his retirement in 2016. In addition to playing good music, Wentworth used his on-air time to talk about the history of roots music.

The diverse programming at WRIU exposed Wentworth to Cajun and Zydeco music. Soon, he partnered with festival promoter Frank Zawacki to produce a Cajun and bluegrass festival. Wentworth and Zawacki made annual pilgrimages to Louisiana in search of talent and food for the event. In its heyday, the festival boasted 5,000 attendees.

Wentworth’s organizational skills made him the ideal candidate to produce the early IBMA Fan Fest events. These were held in English Park in Owensboro, Kentucky, during World of Bluegrass week. Reflecting on the finale of 1993’s event – which concluded with screams for “More!” as 12-year-olds Chris Thile and Cody Kilby polished off a rousing “Mama Don’t Allow” – Wentworth told Keith Lawrence of Owensboro’s Messenger-Inquirer newspaper, “To me, this is what a festival is all about.”

Wentworth further solidified his ties to Owensboro by serving on an 80+ member advisory board that was assembled to guide development of a bluegrass museum. He also served a term on the IBMA Board of Directors.

Wentworth continued to produce the Cajun/bluegrass festival with Frank Zawacki until 1997, at which time the two parted ways. Wentworth then partnered with Mary Tyler Doub in 1998 to co-produce the Rhythm & Roots festival. Other festival activities included helping to organize Winterhawk and being the talent coordinator for Grey Fox (2000-2014).

Health issues necessitated that Wentworth step down from producing the Rhythm & Roots festival in 2022. After careful consideration, Goodworks Entertainment was selected to carry the event forward. Wentworth remained available in an advisory capacity. Recalling his decades-long involvement in music promotion, Wentworth told the Westerly Sun that his proudest achievement was “surviving as an independent festival producer for nearly 40 years in a corporate environment.”

Robert Earl West (July 25, 1944 – January 10, 2024) was a native of Chase City, Virginia, who played bass and sang all parts with Appalachian Express. Prior to his work with this group, he sang in the Virginia Harmony Quartet, a gospel group. He became involved in bluegrass, starting in about 1978, when a friend needed a bass player and asked Earl to handle the chores.

Appalachian Express began locally in 1975 and gradually gained acclaim on a national level. In 1986, the group came in second at a SPBGMA band competition. The following year, the band came in first, beating out 44 other groups. The band also won Virginia State Champion Band honors on three separate occasions.

The band had several self-produced albums, including 1982’s Unquiet Grave. In 1986, Atteiram picked up the group for one album, Old, Old House. The group’s most carefully produced and widely distributed albums appeared on Rebel, starting with the gospel I’ll Meet You in the Morning. A highlight review in Bluegrass Unlimited by Eric Roberts implored that “lovers of bluegrass gospel should begin lining up at the record store immediately to buy this wonderful album of timeless beauty.” The next two years saw additional releases on the label: Express Tracks and Walkin’ the Blues.

Appalachian Express retired in 1992 but, after a 25-year hiatus, returned in 2017 with a self-released disc called Dusty Treasures. Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer Allan Walton noted that the group’s “smooth but powerful vocal stylings (and) strong instrumental work” were still very much in evidence.

In recent years, West suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, Covid-19, and double pneumonia.