Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – July 2022

Notes & Queries – July 2022

Queries

Q: When it comes to Clarence White’s guitars, it seems most of the attention is given (and not inappropriately so) to the iconic 1935 D-28 that ended up in Tony Rice’s hands. But, from what I’ve read, Clarence used the D-28 mostly for rhythm (perhaps owing to it not being set up very well) and used a D-18 for most of his lead playing. I know in later years he came to be associated with Whitebook and Noble guitars, but I’m wondering if anybody knows what became of the D-18, or D-18s if there was more than one, that Clarence relied on for his lead work. Kory Willis, via email.

A: Clarence White/Kentucky Colonels aficionado John Delgatto supplied us with what is likely the most definitive answer available today: Yes, Clarence’s favorite guitar was the infamous D-18. It was the guitar Clarence used to record Appalachian Swing. It was damaged when Roland ran over it with their car by accident during the 1964 summer tour that included the Newport Folk Festival. He had it repaired in Detroit during their gig there by a famous guitar luthier (whose name escapes me). The story goes, which I never got to ask Clarence about but I think is pretty correct, as follows. That D-18 went missing (or stolen) during a recording session in Los Angeles around 1966-’67. It has not appeared anywhere that I know of. That guitar luthier in Detroit probably would have had the Martin serial number which would aid in tracking it down. Rumors over the decades say that it was in the possession of someone in the Santa Barbara, California, area but who really knows. Clarence, though never naming names, had a hunch who did do it. He then turned to his Roy Noble guitar (which I understand is around); he also had a newer D-28 during his days with the Byrds but it was not that great sounding. He was forced to use an Ovation for reasons unknown in some photos and on stage. But he hated that “piece of plastic” as he put it. As the late Mike Longworth was fond of saying, “Put a guitar strap on that guitar and you will have a ‘standing ovation’.” Clarence purchased the Whitebook in early April 1973 just after the videotaping the Bob Baxter TV shows from Fred Walecki’s Westwood Music. I always wished I could find that D-18.

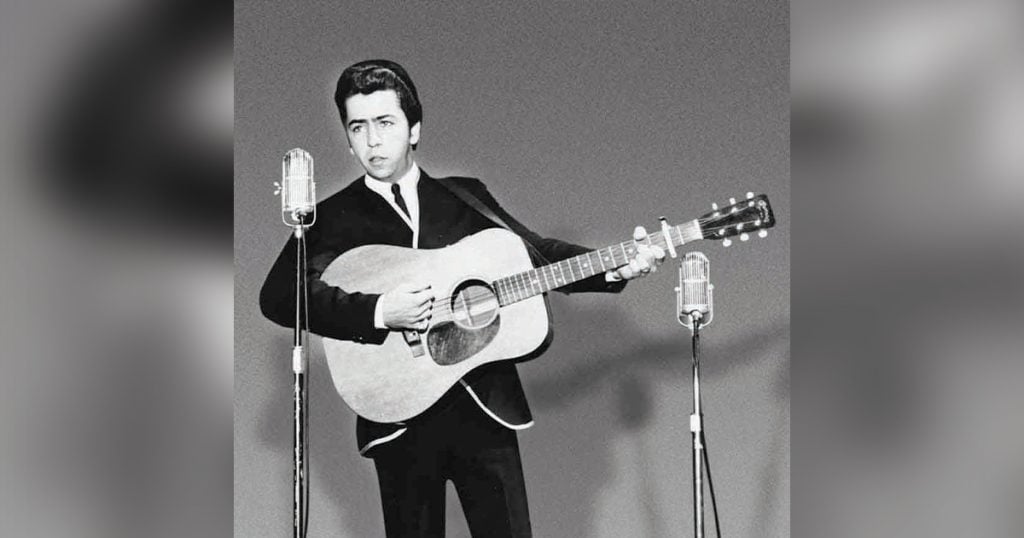

Q: I have a question regarding the song “Casey’s Last Ride,” written by Kris Kristofferson. I’ve always wondered if this unique song has a special story behind it—the lyrics are so poignant, and they leave a question in my mind about the relationship between the man and woman. Cathy Willingham, Mathias, West Virginia.

A: Unfortunately, there’s no definitive answer from the song’s creator. Most artists prefer to let their work speak for itself, which leaves things open to interpretation. Kristofferson did, however, tell author Paul Zollo in More Songwriters on Songwriting, that “the imagery [in the song] goes all the way back to London [in the late 1950s], when I was hanging around there.” It wasn’t until later, in the mid-to-late 1960s, that he worked on finishing the song. While driving through a torrential rain storm in Louisiana, he recalled that “those [verses] just came to me. It seemed I didn’t know whether they would fit together or not. That’s always been one of my favorites.”

Although Kristofferson was trying to establish himself as a songwriter, Fred Foster of Monument Records encouraged him to consider recording as well. Consequently, his debut album, which was titled Kristofferson, was released in April 1970 and contained “Casey’s Last Ride.” It was only a short time later that the Country Gentlemen—at Doyle Lawson’s suggestion—picked up the song for inclusion on their first album for the Vanguard label in 1972.

Some have suggested that there is a connection to Casey Jones, a railroad engineer who lost his life on April 30, 1900, when the train he was operating struck the rear of another train in Vaughn, Mississippi. Throughout the middle and late 1960s, a number of newspapers ran articles commemorating the anniversary of the event, several of which bore headlines of “Casey’s Last Ride.”

The song is broken down into two parts. One depicts Casey’s seemingly unfulfilled life, despite having a “family of his own.” The “rattle of his chains” brings to mind images of Ebeneezer Scrooge’s business partner Jacob Marley, who was doomed to carry the chains of his sins throughout his afterlife. The other part of the song featured a recounting of a recent rendezvous of Casey with a woman from his past. Told from her perspective, it was apparently not a spur of the moment meeting as she “put on new stockings just to please you.” Still, the song raises more questions than it answers. Was the “tear that’s in his eye” a lament for an old love that didn’t work out? Or a domestic situation that he dreaded returning to? Or a reaction to the “dirty smell of dying”?

Q: Lately I’ve come across two versions of the old favorite “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” I’m referring to the recordings by High Fidelity and by Joe Mullins. They’re so similar and harken back to the original, I’m guessing. So different from the popular version (by Roy Acuff and others). Also, is it true that the original was titled “Can the Circle Be Unbroken”? Richard Wrobleski, via email

A: As you suggested, the recordings of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” by High Fidelity and Joe Mullins and the Radio Ramblers are, indeed, modeled after the original version that was first published in 1907. The song is credited to Ada R. Habershon (1861-1918) and Charles H. Gabriel (1856-1932).

Habershon was born in England and was reared in a Christian home. In 1884, she came in contact with evangelists/singers Dwight L. Moody and Ira Sankey while they were in England as part of a preaching tour. They later invited Habershon to visit the United States where she participated in lectures on the Old Testament.

Shortly after the turn of the 1900s, and at the urging of Charles M. Alexander and R. A. Torrey, evangelists and music publishers from the United States who were on a mission in England, Habershon embarked on the creation of over two hundred hymns. “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” was most likely among this batch.

It seems that many of Habershon’s hymns were not songs as much as they were poems. In the case of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” Charles H. Gabriel was credited with composing the music. A native of Iowa whose father conducted singing schools in their home, Gabriel is reported to have had a hand in creation of over seven thousand songs. He was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame in 1982, a full fifty years after his passing.

In the early 1930s, A. P. Carter drastically re-worked the song. He retained the chorus and the melody of the original but added completely different verses. The Carter Family released it on record in 1935 as “Can the Circle Be Unbroken.”

By the middle 1940s, popular quartets such as the Brown’s Ferry Four were singing the Carter Family arrangement while using the original 1907 title. This was later reinforced with recordings by Rose Maddox, the Stanley Brothers, and, of course, the influential early 1970s release by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band.

From the Mailbox

The article on Randy Graham in the May issue of Bluegrass Unlimited elicited the following note from Sid Flannery and Alida Duchene, disc jockeys on Tampa’s WMNF. “The excellent article that you published about long-time outstanding bluegrass musician Randy Graham reminded us of an impromptu disagreement we recently had on air during our bluegrass radio show. One of us claimed, as indicated in the article, that the Bluegrass Cardinals were the first bluegrass band to record a cappella gospel, while the other said that distinction resided with Ralph Stanley. In 1971, Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys recorded an album called Cry From the Cross, which included two songs, “Sinner Man” and “Bright Morning Star,” that had acapella singing inspired by Ralph’s youthful attendance at Primitive Baptist church services in southwest Virginia. It is true that each song has a few single strums of the guitar at rests between the singing, but as the liner notes for the CD reissue of the album describe, that minor technicality went away in other a cappella recordings by the band soon thereafter. It’s all good and hats off to both of these outstanding and precedent setting bluegrass bands.”

Ralph Stanley has generally been given credit for having introduced a cappella singing in bluegrass. As mentioned above, his 1971 Cry From the Cross album for Rebel Records contained two such arrangements. A brief guitar strum was heard at the start of each track, mainly for the purpose of setting the pitch for each of the singers to follow. In other forms of mostly a cappella music, such as Sacred Harp, the same effect is achieved by a lone singer who hums a note to which the other singers then set their pitch. From 1971 to 1975, Ralph Stanley recorded at least eight songs that were given a cappella treatment, most of which contained a pitch-setting guitar strum. These include “Bright Morning Star,” “Gloryland,” “Sinner Man,” “When I Get Home,” “Dark and Stormy is the Desert,” “Great High Mountain,” and “Turn Back.” Ralph’s first truly all-a cappella song (ie, no guitar strums) was recorded in December 1971: “Village Church Yard.”

While the church music of Ralph Stanley’s upbringing is often cited for his later love of a cappella singing, a 1966 tour of Europe that included the Stanley Brothers and Kentucky balladeer Roscoe Holcomb likely served as a pleasant reminder of that style of singing. On the tour, Holcomb invited the Stanley Brothers and George Shuffler to help sing the Primitive Baptist hymn “Village Church Yard.” A recording of the song from a March 17, 1966, performance in Bremen, West Germany, can be heard on a Bear Family 2-CD set called American Folk & Country Music Festival; it sounds very much the same as the a cappella songs that Ralph began recording in the early 1970s. Photos by John Cohen of the New Lost City Ramblers, who was also part of the tour, captured candid photos of Roscoe Holcomb with Carter and Ralph Stanley singing from a Baptist hymnal while on the tour’s bus.

The Bluegrass Cardinals were definitely among the first to also release a cappella songs on record, but their self-titled debut album, with its lovely rendition of “There Is a Fountain,” didn’t appear on the market until 1976, fully five years after Ralph Stanley’s pioneering efforts.

Over Jordan

Kenneth Victor “Kenny” Sidle (July 20, 1931 – September 14, 2021) was a champion Ohio fiddler whose awards included a 1988 Arts Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and a 2012 Ohio Heritage Fellowship Award. As a contest fiddler, he won numerous state championships including ones for Ohio (five times), Pennsylvania (three times), and Kentucky (twice). He also competed at Galax Old Fiddler’s Convention and at the Grand Masters in Nashville.

Sidle came by his love of the fiddle naturally; his father and an uncle were both fiddlers. His father started him out on the fiddle at around age four and a half and at age five he sported his first public appearance on the instrument. Using just one finger and one string on fiddle, Sidle played “Listen to the Mockingbird” at a traveling medicine show.

Around 1946, Sidle’s talents were more ably showcased when he and his sister performed at Newark, Ohio’s Hillbilly Park, as part of the facility’s house band. They later secured radio exposure on WCLT radio, also in Newark. After two years of service in the military that began in 1953, Kenny returned to perform at Hillbilly Park.

Sidle married in 1955 and began raising a family. Preferring a stable home life to that of a traveling musician, he made a career at Owens-Corning Fiberglas of Newark. Still, he found time to fiddle on weekends. In 1967 he became part of the staff band for the Wheeling Jamboree. While there, he declined an offer to join the staff band at the Grand Ole Opry.

Closer to home, Sidle joined the Cavalcade Cut-Ups, a group that performed in Columbus, Ohio, as part of the weekly North American Country Cavalcade. The program was most active in the middle 1970s and was broadcast over radio station WMNI. The same era saw the release of a fiddle album on the Rome label called Favorite Fiddle Tunes. Bluegrass Unlimited tagged the release as a “collection of traditional fiddle tunes laced with a few original numbers by a good central Ohio musician who has done more contest than professional work” and noted that “Kenny Sidle is a fine fiddler who, we are told, plays in the wake of greats like Clark Kessinger.”

Following retirement from Owens-Corning in 1986, Sidle began accepting students who wanted to learn to play the fiddle. According to a 1990 article in the Newark Advocate, “The [Ohio] Arts Council had been after Sidle to teach for several years, particularly after he was named a national music treasure by the National Endowment for the Arts. His retirement . . . gave him time to consider teaching.”

Retirement also afforded time for Sidle to perform at the Paint Valley Jamboree in Bainbridge, Ohio; with a bluegrass band called Frosty Morning; and for square dances at Flowers Hall near his home in Hanover, Ohio. He also released another recording called Fiddle Memories.

Peter Ernest “Pete” Reiniger (February 11, 1949 – May 13, 2022) was a recording engineer/sound supervisor whose primary day job was with Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Former colleagues Dan Sheehy and Jeff Place wrote that “When you listen to nearly any recording released by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings over the past quarter-century, you are listening to Pete’s work.” Indeed, over the years, he assembled an impressive resume that included work on approximately two hundred album and CD projects for the label, many of which were devoted to bluegrass and old-time music.

A native of Troy, New York, Pete first took an interest in music when he was exposed to some Gene Autry 78 rpm records that belonged to his father. Later, at age, his grandfather taught him to play trumpet. Later, in college in the early 1970s, he took up the guitar, learning to play by ear. He graduated from SUNY Potsdam where he majored in theatre arts.

Shortly after graduating, Pete landed at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, where he worked on the Institution’s annual Folklife Festival. He participated in five of the festivals, from 1973 to 1977, and, for the last two years, served as the event’s technical director.

Throughout most of the 1980s, Pete was involved with the National Council for the Traditional Arts for which he traveled the country providing sound for various roots music tours. He performed a similar function on a world-wide basis for tours that were sponsored by the United States Information Agency.

Pete landed back at the Smithsonian in 1991 where he served as the Folklife Festival’s technical director; he remained on board for ten years/events. During much of this time, he was also a part-time employee at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, a status he enjoyed from 1993 until 1999. It was then that Pete was hired full-time by then label director Tony Seeger.

While Pete’s activities with the National Council for the Traditional Arts, the United States Information Agency, and the Smithsonian Folklife Festival put him in touch with a number of bluegrass and traditional musicians, it wasn’t until he started with Smithsonian Folkways that his attachments to bluegrass took on a more definitive role. His toolbox of tricks included everything from engineering, mixing, mastering, and producing to editing, sound supervision, and authoring liner notes. Among the projects that benefitted from a master’s touch (he was known to be a perfectionist!) were Seldom Scene Long Time . . ., The Country Gentlemen On The Road (And More), Ola Belle Reed Rising Sun Melodies, Anthology of American Folk Music (for which Pete won a Grammy for Best Historical Album), Friends of Old Time Music: The Folk Arrival 1961-1965, and The Lilly Brothers & Don Stover Bluegrass At The Roots 1961.

While still employed at Smithsonian Folkways, Pete maintained a small studio at his home. There, as well as at other studios, he recorded projects for other artists and labels including Wayne Henderson Rugby Guitar, Dan Crary Holiday Guitar, Stephen Wade Dancing in the Parlor, Will Keys Banjo Original, and Tony Ellis Sounds Like Bluegrass to Me.