Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – December 2024

Notes & Queries – December 2024

Q – What can you tell us about “Those Two Mirthquakes of Fun” called Shufly and Buckeye Sneezleweed who appeared with Bill Monroe at several shows in 1949? Joe Ross, Roseburg, Oregon.

A – An advertisement for an October 21, 1948, show by Bill Monroe in West Helena, Arkansas, revealed Buckeye Sneezleweed to be Mac Carger, who was then a member of Monroe’s warm-up act, the Shenandoah Valley Trio.

Mack Lowell Carger (May 31, 1919 – March 28, 2014) was an Arkansas farm boy whose father played fiddle and mother played banjo. By the time he was 15, he was playing in a local band. His father died in 1939, leaving Mack to help run the family farm. This ended in 1941 when he was called to military service.

During World War II, Carger experienced 208 days of combat and received a total of 37 different wounds. He was treated at an Army hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he also received a diagnosis of being shell-shocked (PTSD). His medical team advised him to seek employment that was “on the move and around people.” Work in a band setting proved to be just what the doctors had ordered.

At some point after World War II, Carger hooked up with the York Brothers (mentioned in November 2024 “Notes & Queries”), a popular duo that appeared on the Grand Ole Opry. Advertisements from June and July 1948 gave Carger billing with the York Brothers for appearances at movie theatres in Kingsport, Tennessee, and Gate City, Virginia.

It was only a short time later that Carger signed on with Bill Monroe’s troupe. Advertising for the show in West Helena and another on October 22 in Marvell, Arkansas, introduced Carger as Buckeye Sneezleweed, “Arkansas’ Own Mirthquake of Fun.” Carger apparently worked as a solo for a month or so. A November 25, 1948, date in Madisonville, Kentucky, found Sneezleweed paired with “Shufly.” Together, they were billed as “The South’s Funniest Comedy Team.” The tagline appears to be a bit of invention on Monroe’s part as nothing about a comic named Shufly can be found prior to this event. Others on the bill included Benny Martin, Jack Phelps, Don Reno, Joel Price and the Shenandoah Valley Trio. Tom Ewing, author of Bill Monroe – The Life and Music of the Blue Grass Man, weighed in to say that “it’s likely that Shufly was one of the Blue Grass Boys or one of the Shenandoah Valley Trio (possibly one of its original members: Jackie Phelps, G.W. Wilkerson, and Carger). I’m also guessing that Shufly was the straight man of the team, so more than one of them could have played his part. Blackface?”

Carger remained part of the advertising for Monroe’s shows through June of 1949. A June 14 date (the last to feature the duo) in Columbia, Louisiana, featured the Blue Grass Boys in an exhibition baseball game with a local team. Performing on stage were the Blue Grass Boys, the Blue Grass Quartet, Shufly and Sneezleweed, and the Shenandoah Valley Trio.

After leaving Monroe, Carger headed back to Arkansas where he assembled a group called Smilin’ Mac and His Tennessee Partners. In April 1951, he secured a spot on KRLA in Little Rock. He also worked as the station’s country music director.

Carger developed another comedy persona in the form of Ole Cyclone. His performance credits included the Roxy Theatre in New York, the Labor Temple in Detroit, and Little Rock’s Barnyard Frolic that was held at Robinson Auditorium. Among his later endeavors was a stint with the Western Caravan Show and Dance Band. The act was popular in the late 1980s and, according to Carger, brought “Nashville quality to Arkansas.”

Rusty Nail

Intrepid West Coast subscriber Billy Q. Smith is a frequent poster of classic bluegrass clips to YouTube. Oftentimes, his postings revolve around a particular theme or throughline, and are accompanied with interesting historical data. Recently, a 1966 recording by Mac Wiseman called “How Lonely Can You Get” attracted his attention, especially the name of the song’s writer. Rusty Nail sounded, to us, very much like a nickname or pseudonym. Using a variety of sources (Library of Congress website, Ancestry.com, discogs.com, embattled archive.org, and the notes to a Bear Family boxed set of Mac Wiseman recordings to name a few) a brief – and still woefully incomplete – image of the writer began to emerge.

Leading off the search was a single line of text by author Colin Escott in the book for the Wiseman Bear Family collection called On Susan’s Floor: “The composer was a woman who wrote under the name ‘Rusty Nail.’” A check of the Broadcast Music, Inc. website (bmi.com) for the name Rusty Nail revealed a total of 54 songs that were written, or co-written, by Ms. Nail. Several of those songs were then checked against the Copyright Office website which yielded a proper name of Euphia McGee. Ancestry.com then provided most of the rest.

Our writer was born Euphia Elizabeth Jones on March 17, 1917, in Arkansas. On March 2, 1934, while still in Arkansas, she married Claud Armon Nail (hence the name Nail). The couple divorced nearly a decade later, on August 25, 1943. By 1950, she had relocated to Los Angeles with two children in tow. She secured work there as a waitress. The first evidence of her interest in music was a 78-rpm disc that was released (circa 1949-’50) on the Cormac label. The band was billed as Rusty Nail and the Boys of the Trail. Both songs on the disc, “Let Those Brown Eyes Smile at Me” and “Arkansas Waltz,” were written by Nail. The same year (1950) Euphia married for a second time, to a Scottish immigrant named John McGee.

Although it was the Mac Wiseman recording of “How Lonely Can You Get” that sparked the trip down the Rusty Nail rabbit hole, her far-and-away most popular composition was “Let Those Brown Eyes Smile at Me.” The song was in circulation as a performance piece in the middle 1950s when it was featured by Evelyn Wills on an August 22, 1954, broadcast of the Billy Jack Wills television program.

But, it was a pair of releases by Rose Maddox (recorded November 21, 1956, and released November 11, 1957) and Flatt & Scruggs (recorded July 11, 1957, and released August 19, 1957) that put the song on the map.

Although Nail had recorded the song herself in 1949, it was not until February 1957, shortly after the recording by Rose Maddox was made, that she had the song copyrighted and published. She placed it with Golden West Melodies, a West Coast concern that was owned by Gene Autry. It was most likely Golden West pitch-man Troy Martin (see “Notes & Queries” February 2023) who brought the song to the attention of Flatt & Scruggs.

A bit of marketing by Columbia Records in support of the Flatt & Scruggs release tagged the duo as “Stars of the ‘Grand Ole Opry,’ [and that] the boys maintain the highest standards of pure ‘Country’ sound and approach … for which there is always a large demand. [This is] true to their best form . . . your sales will show you!”

Cash Box reviews for both versions were positive. “Music lovers who want their decks straight country are gonna like Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs latest Columbia pressing . . . a persuasive, up-tempo romantic affair that the boys deliver in their wonderful ‘back mountain’ style.” And “here the songstress (Maddox) and a chorus convincingly blend their vocal talents as they wax a heart rending, slightly up-tempo romantic piece. [A strong side] for the jocks, ops and dealers.”

For a period of time, both versions of “Let Those Brown Eyes Smile at Me” were being played simultaneously on country radio. The version by Flatt & Scruggs garnered the most airplay. The release by Rose Maddox fared well and she could always count on spins on KOCS in Ontario, California, where her brother Fred (a former member of the Maddox Brothers & Rose troupe) was a disc jockey.

A third, and less influential, recording of “Let Those Brown Eyes Smile at Me” appeared in 1960 as part of Skeeter Davis’s debut album for RCA Victor, I’ll Sing You a Song and Harmonize Too.

Doubling back to “How Lonely Can You Get,” Wiseman recorded it for Dot Records in May of 1966. Appearing with him on the album were the Osborne Brothers and fiddler Tommy Jackson. It’s likely that Wiseman met songwriter “Rusty” Nail when he moved to California (in 1957) to take a job as a producer for Dot Records. Wiseman not only recorded the song, but he also published it through his Wise-O-Man Music Company. Having a stake in the song no doubt figured into his recording the song again, in 1971, for a duet album with Lester Flatt called On the South Bound.

Wiseman evidently had more irons in the fire with “Rusty” Nail. While serving as the manager of the WWVA Wheeling Jamboree in the middle and late 1960s, Wiseman released a 45-rpm single by Carl Cody on his own label, Wise Records. Both songs, “I Gotta Get a Bottle” and “You’re Gonna Cry,” were co-written by Nail. Cody and his group, the Country Boys, appeared on KXLA in Pasadena, California.

“How Lonely Can You Get” remains one of the least-covered songs in bluegrass, with only two known copies by Del McCoury and the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band. Conversely, “Let Those Brown Eyes Smile at Me” enjoyed wide coverage with recordings by Bobby Atkins, the Blue Ridge Mountaineers, the Bluegrass Pioneers, the Boutilier Brothers (from Canada), the Carolina Rebels, the Country Pickers (from Switzerland), J. T. Crowe (that’s not a typo!), the Double Mountain Boys, Five of a Kind, Melvin Goins, Les Hall & the Mastertones, the Jones Brothers, Al Jones and Frank Necessary, Wayne Lewis, Bill Millsaps, Old & In the Gray, the Pike Family, Jeff Presley, James Price, the Larry Stephenson Band, the Suggins Brothers, the Suwannee Valley Gang, Garry Thurmond and the Warrior River Boys, Jesse Travis, and David West.

Still Missing Jim Clark

Reader Doug Bailey wrote that “I’ve been a subscriber to Bluegrass Unlimited since the late ‘70s. After all these years, I still enjoy reading it every month. I’m responding in reference to your inquiry, “Where is Jim Clark?” Although I have no idea of his whereabouts, I thought I would take a few minutes to recollect about his festivals.

“At the time, they were called “Supergrass.” The first one I went to was in Shade Gap, Pennsylvania, in 1978. The only band I recall seeing was Red Allen, with Porter Church on banjo. Needless to say, they were excellent. I don’t recall any of the other bands, but I do vividly recall how unorganized the festival was run. Nothing was on time and it was chaotic. Motorcycles ran, very loudly, throughout the campground all night. One good moment was picking late at night with a man who said he was Earl Taylor. I have no way to verify it was him, but the guy could pick and sing. I heard there was a shooting at the 1979 Shade Gap festival, but I have no way of verifying if that was true.

“The second festival I attended was near Latrobe, Pennsylvania, in 1981. Since it was close to home, I didn’t camp. I recall seeing Jim and Jesse and Jimmy Martin. As with the 1978 festival, it was extremely unorganized and bands did not start on time.

“If you bought a ticket to one of Clark’s festivals, he sent you a t-shirt with each ticket. I still have both t-shirts. I’ve attached pictures of both.”

Over Jordan

Tom Gray remembers Thomas Hudson “Tom” Morgan (April 19, 1932 – September 26, 2024). He was the first bassist to be a member of the Country Gentlemen; the band was formed in July of 1957. After a tragic car crash that almost killed three members of Buzz Busby’s Bayou Boys, the one remaining member, Bill Emerson, called John Duffey and Charlie Waller to fill the next night’s gig. A friend who had never played a bass had been enlisted by Bill to try to play the bass that night. Liking the way they sounded together, Bill, Charlie, and John decided to form a new band, and adopted the name The Country Gentlemen. The first thing they did was to hire a real bassist. That bassist was Tom Morgan. Tom also played guitar with Buzz Busby, and bass with Red Allen’s Kentuckians which included Frank Wakefield and Pete Kuykendall in the 1960s.

I owe great thanks to Tom Morgan for starting me on the road to becoming a bluegrass bassist. In the 1950s, when I met Tom, he was in the U.S. Air Force, stationed at the Pentagon and living in Takoma Park, Maryland. After a jam session/rehearsal at my parent’s house in Washington, he left his bass in the basement overnight. Finally, I had a chance to try my hand at playing that big instrument. I had been playing bass runs on my guitar, wishing I could get my hands on a real bass to try them out. Now I got the chance to play one. That did it! I spent the money from my paper route and bought my own bass in 1956. After I’d been playing a year, Tom gave me some advice to not be showing off all the time.

Perhaps Tom Morgan’s greatest fame was as a luthier. He claimed that he has destroyed more banjos than anyone else in the world! He was an expert at converting 4-string tenor or plectrum banjos to 5-string bluegrass banjos. In that trade, he taught many others his craft, including his son Scott, who became a great guitar maker. Tom commented once that the world needed a better autoharp, one with the acoustic qualities of a fine guitar. So, he designed and built the Morgan autoharp, made with a fine spruce top and bracing like that in a Martin guitar.

Once he retired from the Air Force and moved back to his native Tennessee, I saw him only occasionally at festivals. A most memorable get-together was in 2007 at the 50th anniversary celebration of the Country Gentlemen at Watermelon Park in Berryville, Virginia. He and I and his partner Lynne Haas sat at his camper and sang all the Bailes Brothers songs we knew. Rest in peace, my dear friend. (Submitted by Tom L. Gray.)

As Tom Gray’s remembrance so eloquently detailed, Tom Morgan’s roots in old-time music ran deep. During the Civil War, his great uncle Bill played bugle and fiddle in Company B, 6th Tennessee Mounted Infantry, and his grandfather, G.W. Morgan, played violin and sang. More immediately, Tom’s father played guitar, harmonica, and sang, and both his parents sang together at home. But it was the music of the Grand Ole Opry that, as early as six years old, really captured his interest.

Following graduation from high school, Morgan attended the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. While there, he befriended several of the entertainers that appeared on the WNOX Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round and on the Cas Walker Show. For a brief period of time, he played bass for Carl Butler. He joined his first band and played several gigs around school. One memorable music highlight from this period was seeing Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys in concert at the American Theater in Chattanooga on June 22, 1951; this would have been only a few days after Carter Stanley had joined the group.

In 1952, as the Korean War was heating up, Morgan joined the Air Force. Following basic training and several temporary assignments, he was stationed in the Washington, DC / Northern Virginia area. In tow was his new bride, the former Mary Newell from Dayton, Tennessee.

Morgan wasted no time in finding musical opportunities. He joined a group called the Log Cabin Boys. Other band members included 17-year-old Pete Kuykendall (who was just starting to play the fiddle), Harper Kirby on mandolin, Paul Champion on banjo, and Dan Conner on guitar. Don Owens of WARL in Arlington, Virginia, lent encouragement to the new band. A later grouping found Morgan performing with fiddler Carl Nelson and banjoist Smiley Hobbs.

It was during this time frame that Morgan became interested in instrument construction and repair. After his stint with the Country Gentlemen, he was given a temporary Air Force assignment in Alaska. A banjo neck belonging to Ralph Stanley made its way on a circuitous route to the frigid northland for deft repair work by Morgan. After returning to the Lower 48, he later worked on Carter Stanley’s Martin D-28 guitar, outfitting it with a new neck that gave the appearance of a D-45 model. His friendship with the Stanleys led to his occasionally filling in with them when they were in the DC area without a bass man.

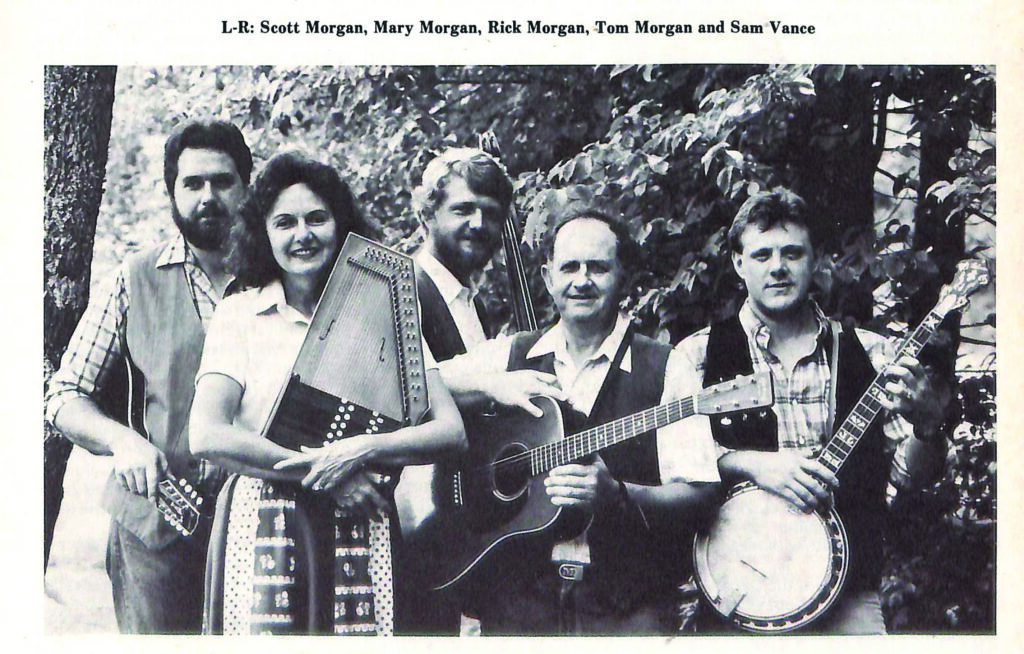

After returning to Tennessee in the early 1970s, Morgan busied himself with building a new home, working on instrument repair and construction, and performing with his family band: The Morgans. The group consisted of Tom on guitar, Mary on autoharp, and sons Scott and Rick on mandolin and bass. A core mission of the group was to take the music to schools where children of their region could be introduced to what had once been a vital part of life in central Appalachia. An added feature of the group from 1977 to 1989 was legendary country fiddler Curly Fox.

In 1993, Morgan lost his wife of 40 years to cancer. In 1999, he took on a partner, Lynne Haas, to assist with the music in the schools programs. He is survived by his daughter, Melissa Jo Morgan Foster, grandchildren Richard Paul Morgan, Zachary Scott Morgan, Sarah Beth Morgan, Coralee Hall, and Saralyn Lilly, and his great granddaughter Courtney Melissa Hall.